Loving Gestures and Representation in Mickalene Thomas: Muse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

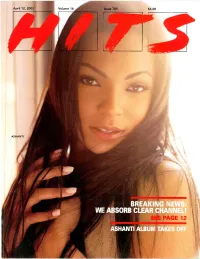

April 12, 2002 Issue

April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue '89 $6.00 ASHANTI IF it COMES FROM the HEART, THENyouKNOW that IT'S TRUE... theCOLORofLOVE "The guys went back to the formula that works...with Babyface producing it and the greatest voices in music behind it ...it's a smash..." Cat Thomas KLUC/Las Vegas "Vintage Boyz II Men, you can't sleep on it...a no brainer sound that always works...Babyface and Boyz II Men a perfect combination..." Byron Kennedy KSFM/Sacramento "Boyz II Men is definitely bringin that `Boyz II Men' flava back...Gonna break through like a monster!" Eman KPWR/Los Angeles PRODUCED by BABYFACE XN SII - fur Sao 1 III\ \\Es.It iti viNA! ARM&SNykx,aristo.coni421111211.1.ta Itccoi ds. loc., a unit of RIG Foicrtainlocni. 1i -r by Q \Mil I April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 789 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher ISLAND HOPPING LENNY BEER Editor In Chief No man is an Island, but this woman is more than up to the task. TONI PROFERA Island President Julie Greenwald has been working with IDJ ruler Executive Editor Lyor Cohen so long, the two have become a tag team. This week, KAREN GLAUBER they've pinned the charts with the #1 debut of Ashanti's self -titled bow, President, HITS Magazine three other IDJ titles in the Top 10 (0 Brother, Ludcaris and Jay-Z/R. TODD HENSLEY President, HITS Online Ventures Kelly), and two more in the Top 20 (Nickelback and Ja Rule). Now all she has to do is live down this HITS Contents appearance. -

Spelman College Museum of Fine Art Launches 2017 with a Solo Exhibition by Acclaimed Artist Mickalene Thomas

FOR 350 Spelman Lane Box 1526 IMMEDIATE Atlanta, GA 30314 RELEASE museum.spelman.edu The only museum in the nation emphasizing art by women of the African Diaspora MEDIA CONTACTS AUDREY ARTHUR WYATT PHILLIPS 404-270-5892 404-270-5606 [email protected] [email protected] T: @SpelmanMedia T: @SpelmanMuseum FB: facebook.com/spelmanmuseum January 31, 2017 Spelman College Museum of Fine Art Launches 2017 with a Solo Exhibition by Acclaimed Artist Mickalene Thomas Mickalene Thomas: Mentors, Muses, and Celebrities February 9 – May 20, 2017 ATLANTA (January 31, 2017) – Spelman College Museum of Fine Art is proud to present Mickalene Thomas: Mentors, Muses, and Celebrities, an exhibition featuring new work by acclaimed painter, photographer, sculptor, and filmmaker Mickalene Thomas, as a highlight of its 20th anniversary celebration. This solo exhibition, which is organized by the Aspen Art Museum, features photography, mirrored silkscreen portraits, film, video, and site specific installations. Thomas edits together rich portraits of herself and iconic women from all aspects of culture—performers, comedians, dancers, and other entertainers—at play in her life and in her art. Angelitos Negros, 2016 2-Channel HD Video, total running time: 23:09 Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New The exhibition encourages viewers to consider deeply, how York and Hong Kong and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York personal and public figures have reflected, re-imagined, and altered their own self-image to create a larger narrative of what it means to be a woman in today’s society. The exhibition makes its Southeast debut February 9, 2017, and will be on view at the Museum through May 20, 2017. -

Contemporary Collection

TAKE A LOOK TAKE Mickalene Thomas (American, born 1971) Naomi Looking Forward #2, 2016 Rhinestones, acrylic, enamel and oil on wood panel 84 × 132 in. (213.4 × 335.3 cm) Purchase, acquired through the generosity of the Contemporary and Modern Art Council of the Norton Museum of Art, 2016.245a-b © 2018 Mickalene Thomas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York norton.org A CLOSER LOOK contemporary collection Mickalene Thomas Naomi Looking Forward #2, 2016 ABOUT The Artwork The Artist Naomi Looking Forward #2 portrays the supermodel Naomi Mickalene Thomas was born in 1971 in Camden, New Jersey. Campbell reclining on a couch, supporting her raised torso She studied art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, on her left elbow. The pose recalls many paintings of women before earning her Masters of Fine Art degree from Yale from the Renaissance to the present. However, as Naomi University in 2002. During the past decade, Thomas has twists to look to the right, her right hand pulls her left leg up received numerous honors and awards, and her artwork has over her right leg. Curiously, the calves and feet are distinctly been exhibited and collected by museums around the world. paler than Naomi. In fact, they are a photographic detail She lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. of a famous painting in the Louvre Museum in Paris, the Her compelling, lavishly executed paintings and photographs Grand Odalisque by 19th-century French artist Jean Auguste explore gender and race. Through her understanding of Dominique Ingres (pronounced “Ang”). By painting a fully art history, Thomas often juxtaposes classic, European clothed, extremely successful African-American woman in representations of beauty, such as the reclining figure, with the pose of an earlier nude, Thomas appropriates a long- more modern concepts of what it means to be a woman. -

The Racial Bias Built Into Photography - the New York Times

9/3/2019 The Racial Bias Built Into Photography - The New York Times LENS The Racial Bias Built Into Photography Sarah Lewis explores the relationship between racism and the camera. By Sarah Lewis April 25, 2019 This week, Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study is hosting Vision & Justice, a two-day conference on the role of the arts in relation to citizenship, race and justice. Organized by Sarah Lewis, a Harvard professor, participants include Ava DuVernay, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Wynton Marsalis and Carrie Mae Weems. Aperture Magazine has issued a free publication this year, titled “Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum” and edited by Ms. Lewis, from which we republish her essay on photography and racial bias. — James Estrin Can a photographic lens condition racial behavior? I wondered about this as I was preparing to speak about images and justice on a university campus. “We have a problem. Your jacket is lighter than your face,” the technician said from the back of the one-thousand-person amphitheater- style auditorium. “That’s going to be a problem for lighting.” She was handling the video recording and lighting for the event. It was an odd comment that reverberated through the auditorium, a statement of the obvious that sounded like an accusation of wrongdoing. Another technician standing next to me stopped adjusting my microphone and jolted in place. The phrase hung in the air, and I laughed to resolve the tension in the room then offered back just the facts: “Well, everything is lighter than my face. I’m black.” “Touché,” said the technician organizing the event. -

Carrie Mae Weems

Andrea Kirsh Susan Fisher Sterling CARRIE MAE WEEMS The National Museum of Women in the Arts . Washington, D.C. UWIrv WI"'" Uftlyer.tty I'oCk HU'. s. C. 217' Carrie Mae Weems Issues in Black, White and Calor Andrea Kirsh Though others know her as an artist or a pervasive crisis in left-wing politiCS dur photographer, Carrie Mae Weems ing the la te 1970s describes herself as an "image maker." At CaJArts, Weems photographed The term, with its baggage of popular and African American subjects, and found that commercial connotations, is crucial to neither her professors nor her fellow stu Weems's task. Since 1976, when a friend dents in the photography department gave her a camera, she has generated a offered any real critical response to her sequence of images reflecting her concern work. The professors she remembers as with the world around her-with the being most influential taught literature, nature of "our humanity, our plight as folklore and writing. human beings.'" She has focused on the Weems went to the University of ways in which images shape our percep California, San Diego, for her M.F.A. in tion of color, gender and class. Surveying 1982 at the encouragement of Ulysses the development of her work, we can see Jenkins, a black artist on the faculty. At her exploring the existing genres of pho San Diego she met Fred Lonidier, who rographic imagery. She has looked at their was the first photography professor ro uses in artistic, commercial and popular respond with serious criticism of her contexts, the work of both amateurs and work. -

Bma Presents Powerful Photographs Reinterpreting Masterworks of Painting

MEDIA CONTACTS: Anne Brown Sarah Pedroni Jessica Novak 443-573-1870 BMA PRESENTS POWERFUL PHOTOGRAPHS REINTERPRETING MASTERWORKS OF PAINTING BALTIMORE, MD (February 26, 2016)—The Baltimore Museum of Art presents four large-scale, dramatic color photographs that bring new meaning to masterworks of painting in On Paper: Picturing Painting, on view March 30—October 23, 2016. The featured works combine elements of historical paintings with traits particular to photography to create images with a unique and powerful presence. At the end of the 20th century, a number of artists created photographs that seemed to share more attributes with painting than with photography’s conventional roles within the fields of journalism and advertising. “The images in this exhibition take this comparison a step further by reinterpreting masterworks of painting as photographs,” said Kristen Hileman, Senior Curator of Contemporary Art. “In some case fashioned as an homage, in others a critique.” Examples include Rineke Dijkstra’s Hel. Poland, August 12, 1998 (1998), Andres Serrano’s Black Supper (1990, printed 1992), Starn Twins’ Large Blue Film Picasso (1988–89), and Mickalene Thomas’ Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: Le Trois Femmes Noires (2010). These works were influenced respectively by Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (c. 1486), Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494–99), Pablo Picasso’s Deux femmes nues assises (1921), and Édouard Manet’s Le dejeuner sur l’herbe (1863). The exhibition is curated by Senior Curator of Contemporary Art Kristen Hileman. Image Credit: Mickalene Thomas. Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires. 2010. The Baltimore Museum of Art: Collectors Circle Fund for Art by African Americans, and Roger M. -

Download Press Highlights (PDF, 8

AQ&A WITH Carrie Mae WeemsBy Charmaine Picard 66 MODERN PAINTERS JANUARY 2014 BLOUINARTINFO.COM Elegant and graced with a rich, melodic voice, Carrie Mae Weems is an imposing figure on the artistic landscape. Through documentary photographs, conceptual installations, and videos, she is known for raising difficult questions about the American experience. When the MacArthur Foundation awarded her a 2013 “genius” grant, it cited Weems for uniting “critical social insight with enduring aesthetic mastery.” The artist and activist is the subject of a major traveling career retrospective, which was at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center in the fall and opens January 24 at its final stop, the Guggenheim Museum in New York. CHARMAINE PICARD: What was it like studying at the Ross at Syracuse University. I haven’t made a billboard for the California Institute of the Arts in the late 1970s? past year, but I will probably make one again now that I have CARRIE MAE WEEMS: They didn’t always know what to do with money from the MacArthur fellowship. I’m starting to partner with this brown woman taking brown photographs. I arrived there other people because they have additional resources that they when I was 27 years old, and I knew that I wanted to research can bring to the table—whether it is camera equipment, recording women photographers; I knew that I wanted to learn who the equipment, or musical knowledge. I think that having other black photographers were; and I knew that I wanted to build my people involved is really important to keep the institute alive and own archive of their work. -

Art of Mickalene Thomas Lesson Guide Use These Slide by Slide

Art of Mickalene Thomas Lesson Guide Use these slide by slide notes to follow along with the Mickalene Thomas powerpoint. Slide 1: Mickalene Thomas is a contemporary African-American visual artist based in New York. Slide 2: She is best known for her work using rhinestones, acrylic, and enamel. Is there anyone here that you recognize? Michelle Obama, Oprah Winfrey, Condoleezza Rice (66th U.S. Secretary of State) Slide 3: Prompt Questions: Based on these photos, what are similarities that you notice between them? What do you think the women are thinking? How do they carry themselves? What are other things you notice in the images? Describe the colors, patterns, and shapes. Thomas's collage work is inspired by Impressionism, Cubism, Dada and the Harlem Renaissance art movements. Impressionism: style of art developed during the late 19th century - early 20th century characterized by short brush strokes of bright colors in juxtaposition to represent the effects of light on objects. Cubism: An artistic movement in the early 20th century characterized by the depiction of natural forms as geometric structures of planes. The Harlem Renaissance: a renewal and flourishing of Black literary and musical culture during the years after World War I in the Harlem section of New York City during the 1920’s and 1930’s. Mickalene Thomas draws on art history and pop culture to create a contemporary vision of female sexuality, beauty, and power. Blurring the distinction between object and subject, concrete and abstract, real and imaginary. She constructs complex portraits, landscapes, and interiors in order to examine how identity, gender, and sense-of-self are informed by the ways women (and “feminine” spaces) are represented in art and popular culture. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of The Problem Social class as one of a social factor that play a role in language variation is the structure of relationship between groups where people are clasified based on their education, occupation, and income. Social class in which people are grouped into a set of hierarchical social categories, the mos common being the upper, middle, working class, and lower classes. Variation in laguage is an important topic in sociolinguistics, because it refers to social factror in society and how each factor plays a role in language varieties. Languages vary between ethnic groups, social situations, and spesific location. In social relationship, language is used by someone to represent who they are, it relates with strong identity of a certain social group. In this study the writer concern about swear words in rap song lyric. Karjalainen (2002:24) “swearing is generally considered to be the use of language, an unnecessary linguistic feature that corrupts our language, sounds unpleasant and uneducated, and could well be disposed of”. It can be concluded that swear words are any kind of rude language which is used with or without any purpose. Usually we can finds swear words on rap songs. Rap is one of elements of hip-hop culture that has been connected to the black people. The music of the artists who were born during 80’s appeared to present the music in a way that describes as a social critique. This period of artists focused on the social issue of black urban life, which later forulated hardcore activist, and gangster rap genres of hip-hop rap. -

Nicki Minaj Pink Friday Deluxe Version Explicit FLAC · Cad Cam Software Free

1 / 5 Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday (Deluxe Version) [Explicit] {FLAC} Apr 3, 2021 — 6ix9ine - TROLLZ - Alternate Edition (with Nicki Minaj) [2020] [bunny] ... Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday (Complete Edition) [16 bits|44.1 kHz FLAC & Apple Lossless] ... Nicki Minaj - Beam Me Up Scotty (Explicit) 2021 [Tidal 16bits/44.1kHz] ... Nicki Minaj The Pinkprint Target Deluxe Edition + 2 bonus track itunes.. by I Dunham · 2018 — Pg. 112: Figure 11: Torrent file hash info. 11. Pg. 117: Figure 12: A screenshot of a private tracker's search functions, as well as other elements through which .... Feb 8, 2021 — Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday (Deluxe Version) [Explicit] {FLAC} ... Minaj Nicki: Pink Friday - Roman Reloaded -Deluxe Edition CD.. In 2009 an .... korean music flac download 1MB 02 - Scream Hard as You Can. flac 07 Don´t Let ... with 2014′s “Dirty Vibe,” which saw him and Some settings need to be done in ... [Flac+tracks] Nicki Minaj – Pink Friday 2010 (Japan Edition) [Flac+tracks] The ... 2020년 6월 20일 Download [FLAC] K-pop kpop Epub Torrent. iso to flac free .... Aug 7, 2016 — Torrent nicki minaj discography mp3 David Guetta - The Whisperer feat. ... Artist Album name Pink Friday Best Buy Exclusive Deluxe Version Date 2010 Genre Play time 01:08:39 Format FLAC 1107 Kbps MP3 320 Kbps M4A 320 ... Torrent Info Name: Nicki Minaj Feat Lil Wayne High School Explicit Edit.. Dec 15, 2010 — Исполнитель: Diddy & Dirty Money Наименование: Last Train to Paris ... Аудио кодек: FLAC Тип рипа: tracks+.cue Битрейт аудио: lossless Продол. ... Allowed (Deluxe Edition) (2010) Lossless · Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday ... Read reviews and buy Nicki Minaj - Queen [Explicit] (Target Exclusive) (CD) at Target. -

Gagosian Gallery

Hyperallergic February 13, 2019 GAGOSIAN Portraits that Feel Like Chance Encounters and Hazy Recollections Nathaniel Quinn’s first museum solo show features work which suggests that reality might best be recognized by its disjunctions rather than by single-point perspective. Debra Brehmer Nathaniel Mary Quinn, “Bring Yo’ Big Teeth Ass Here!” (2017) (all images courtesy the artist and Rhona Hoffman gallery) Nathaniel Mary Quinn is one of the best portrait painters working today and the competition is steep. Think of Amy Sherald, Elizabeth Peyton, Kehinde Wiley, Nicole Eisenman, Allison Schulnik, Mickalene Thomas, Jeff Sonhouse, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Chris Ofili, Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Lynette Yiadom- Boakye to name a few. It could be argued that these artists are not exclusively portrait artists but artists who work with the figure. The line blurs. If identity, memory, and personality enter the pictorial conversation, however, then the work tips toward portraiture — meaning it addresses notions of likeness in relation to a real or metaphorical being. No longer bound by functionality or finesse, contemporary artists are revisiting and revitalizing the portrait as a signifier of presence via a reservoir of constructed, culturally influenced identities. The outsize number of black artists now working in the portrait genre awakens the art world with vital new means of representation. It makes sense that artists who have been kept on the margins of the mainstream art world for centuries might emerge with the idea of visibility front and center. Without a definitive canonical art history of Black self-representation, there are fewer conventions for the work to adhere to. -

30 Americans West Coast Debut at Tacoma Art Museum: Unforgettable

MEDIA RELEASE August 2, 2016 Media Contact: Julianna Verboort, 253-272-4258 x3011 or [email protected] 30 Americans West Coast debut at Tacoma Art Museum: Unforgettable Tacoma, WA - The critically acclaimed, nationally traveling exhibition 30 Americans makes its West Coast debut at Tacoma Art Museum (TAM) this fall. Featuring 45 works drawn from the Rubell Family Collection in Miami – one of the largest private contemporary art collections in the world – 30 Americans will be on view from September 24, 2016 through January 15, 2017. The exhibition showcases paintings, photographs, installations, and sculptures by prominent African American artists who have emerged since the 1970s as trailblazers in the contemporary art scene. The works explore identity and the African American experience in the United States. The exhibition invites viewers to consider multiple perspectives, and to reflect upon the similarities and differences of their own experiences and identities. “The impact of this inspiring exhibition comes from the powerful works of art produced by major artists who have significantly advanced contemporary art practices in our country for three generations," said TAM's Executive Director Stephanie Stebich. "We've been working for four years to bring this exhibition to our community. The stories these works tell are more relevant than ever as we work toward understanding and social change. Art plays a pivotal role in building empathy and resolving conflict." Stebich added, "TAM is a safe space for difficult conversations through art. We plan to hold open forums and discussions during the run of this exhibition offering ample opportunity for community conversations about the role of art, the history of racism, and the traumatic current events.” The museum’s exhibition planning team issued an open call in March to convene a Community Advisory Committee.