Nomadic Encounters with Art and Art Education DISSERTATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Deception Gives an Excellent Overview of All Things Egyptian

About the Author Moustafa Gadalla was born in Cairo, Egypt in 1944. He gradu- ated from Cairo University with a Bachelor of Science degree in civil engineering in 1967. He immigrated to the U.S.A. in 1971 to practice as a licensed professional engineer and land surveyor. From his early childhood, Gadalla pursued his Ancient Egyp- tian roots with passion, through continuous study and research. Since 1990, he has dedicated and concentrated all his time to re- searching the Ancient Egyptian civilization. As an independent Egyptologist, he spends a part of every year visiting and studying sites of antiquities. Gadalla is the author of ten internationally acclaimed books. He is the chairman of the Tehuti Research Foundation—an interna- tional, U.S.-based, non-profit organization, dedicated to Ancient Egyptian studies. Other Books By The Author [See details on pages 352-356] Egyptian Cosmology: The Animated Universe - 2nd ed. Egyptian Divinities: The All Who Are THE ONE Egyptian Harmony: The Visual Music Egyptian Mystics: Seekers of the Way Egyptian Rhythm: The Heavenly Melodies Exiled Egyptians: The Heart of Africa Pyramid Handbook - 2nd ed. Tut-Ankh-Amen: The Living Image of the Lord Egypt: A Practical Guide Testimonials of the First Edition: Historical Deception gives an excellent overview of all things Egyptian. The style of writing makes for an easy read by the non- Egyptologists amongst us. Covering a wide variety of topics from the people, language, religion, architecture, science and technol- ogy it aims to dispel various myths surrounding the Ancient Egyp- tians. If you want a much better understanding of Ancient Egypt, then you won’t be disappointed be with the straight forward, no-non- sense approach to information given in Historical Deception. -

Kino, Carol. “Rebel Form Gains Favor. Fights Ensue.,” the New York Times, March 10, 2010

Kino, Carol. “Rebel Form Gains Favor. Fights Ensue.,” The New York Times, March 10, 2010. By CAROL KINO Published: March 10, 2010 ONE snowy night last month, as New Yorkers rushed home in advance of a coming blizzard, more than a hundred artists, scholars and curators crowded into the boardroom of the Museum of Modern Art to talk about performance art and how it can be preserved and exhibited. The event — the eighth in a series of private Performance Workshops that the museum has mounted in the last two years — would have been even more packed if it weren’t for the weather, said Klaus Biesenbach, one of its hosts and the newly appointed director of the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center. After seeing the R.S.V.P. list, he had “freaked out,” he said, and worried all day about overflow crowds. As it was, he and his co-host, Jenny Schlenzka, the assistant curator of performance art at the museum, were surrounded at the conference table by a Who’s Who of performance-art history, including Marina Abramovic, the 1970s performance goddess from Belgrade whose retrospective, “The Artist Is Present,” opens Sunday atMoMA; the much younger Tino Sehgal, whose latest show of “constructed situations,” as he terms them, just closed at the Guggenheim Museum; Joan Jonas, a conceptual and video art pioneer of the late 1960s who usually creates installations that mix performance with video, drawing and objects; and Alison Knowles, a founding member of the Fluxus movement who is known for infinitely repeatable events involving communal meals and foodstuffs. -

Art 381 Repeat Perform Record

Sculpture 381 Fall 2013 T/Th 1-4 Repeat, Perform, Record Billy Culiver E.A.T. 9 Evening in Art and Technology A Class Exploring the Intersection Between Theater, Dance and Visual Art The studio art course, Repeat, Perform, Record we will consider the dynamic of live bodies in physical spaces and read critical text and philosophical ideas about performance art. You will have 3 assignment: 1. Work Ethic-Duration/Record, 2. Work Ethic Labor and a collaborative work done with dancers, 3. Spaces Created by Action/Action Created by Spaces. Each assignment is directly aligned to a set of readings and visiting artists who will join the class. In this class, I attempt to honor the radical roots of Performance Art, with its history of expanding notions of how we make art, how we witness art, and what we understand the function of art to be. Performance art in the studio art context emerged from the visual and plastic arts rather than the traditional categories of dance and theater. From the beginning “Performance” was part of the modernist movements such as Futurism, Dada. With the emergence of Fluxus, Situationalism, Happenings, and Conceptualist practices the correspondence with the conscious use of space, time and process became central to Performance Art. With in the last decade, the concept of space, time and process have blended to expand Performance Art, making it a contemporary tool for expression with diverse directions of visual art, theater, dance, music and social practices. Contemporary live art now employs many different forms of experimentation diminishing the known or rehearsed dynamics of performance by opening it to improvisation and chance operations. -

Lefebvre and Maritime Fiction Frank, Søren

University of Southern Denmark Rhythms at Sea Lefebvre and Maritime Fiction Frank, Søren Published in: Rhythms Now Publication date: 2019 Document version: Final published version Document license: CC BY-NC-ND Citation for pulished version (APA): Frank, S. (2019). Rhythms at Sea: Lefebvre and Maritime Fiction. In S. L. Christiansen, & M. Gebauer (Eds.), Rhythms Now: Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis Revisited (pp. 159-88). Aalborg Universitetsforlag. Interdisciplinære kulturstudier https://aauforlag.dk/shop/e-boeger/rhythms-now-henri-lefebvres-rhythmanalysis- re.aspx Go to publication entry in University of Southern Denmark's Research Portal Terms of use This work is brought to you by the University of Southern Denmark. Unless otherwise specified it has been shared according to the terms for self-archiving. If no other license is stated, these terms apply: • You may download this work for personal use only. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying this open access version If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details and we will investigate your claim. Please direct all enquiries to [email protected] Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Aalborg Universitet Rhythms Now Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited Christiansen, Steen Ledet; Gebauer, Mirjam Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Christiansen, S. L., & Gebauer, M. (Eds.) (2019). Rhythms Now: Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited. -

Golden Blade

A APPROACH TO CONTEMPORARY QUESTIONS IN THE LIGHT OF ANTHROPOSOPHY The Golden Blade The Occult Basis of Music RudoljSteiner A Lecture, hitherto untranslated, given at Cologne on December 3, 1906. A M u s i c a l P i l g r i m a g e Ferdinand Rauter Evolution; The Hidden Thread John Waterman The Ravenna Mosaics A. W.Mann Barbara Hepworth's Sculpture David Lewis Art and Science in the 20th Century George Adams THE Two Faces of Modern Art Richard Kroth Reforming the Calendar W alter Biihler Dramatic Poetry- and a Cosmic Setting Roy Walker With a Note by Charles Waterman The Weather in 1066 Isabel Wyatt An Irish Yew E.L.G. W. Christmas by the Sea Joy Mansfield Book Reviews hy Alfred Heidenreich, Adam Bittleston Poems by Sylvia Eckersley and Alida Carey Gulick and H. L. Hetherington Edited by Arnold Freeman and Charles Waterman 1956 PUBLISHED ANNUALLY SEVEN AND SIX The Golden Blade The Golden Blade Copies of the previous issues are available in limited numbers 1956 The contents include :— 1949 '95" The Threshold in S'niure and in Spiritual Knowledge : A Way of The Occult Basis of Music Rudolf Steiner I Man RLT50I.|' STEI.ski; Life Rudolf Steiner Tendencies to a Threefold Order Experience of liirth and Dealh A Lecture given at Cologne .A. C". Harwogi) in Childhood Kari. Konig, m.d. on Decembers, 1906. Goethe and the .Science of the Whal is a Farm ? Future riKORC.R Adams C. A. .Mier A M u s i c a l P i l g r i m a g e F e r d i n a n d R a u t e r 6 H7;n/ is a Heatlhy ."Society? Meditation and Time John Waterman 18 C i i A R L K S \ V a t i ; r . -

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: a Question of the Body and Its Reflections As Gesture

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: A Question of the Body and its Reflections as Gesture. ...material action is painting that has spread beyond the picture surface. The human body, a laid table or a room becomes the picture surface. Time is added to the dimension of the body and space. - "Material Action Manifesto," Otto Muhl, 1964 VIS 2 Winter 2017 When: Thursday: 6:30 p.m. to 8:20p.m. Where: PCYNH 106 Professor: Ricardo Dominguez Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Thursday. 11:00 a.m. to Noon. Room: VAF Studio 551 (2nd Fl. Visual Art Facility) The body-as-gesture has a long history as a site of aesthetic experimentation and reflection. Art-as-gesture has almost always been anchored to the body, the body in time, the body in space and the leftovers of the body This class will focus on the history of these bodies-as-gestures in performance art. An additional objective for the course will focus on the question of documentation in order to understand its relationship to performance as an active frame/framing of reflection. We will look at modernist, contemporary and post-contemporary, contemporary work by Chris Burden, Ulay and Abramovic, Allen Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, Anne Hamilton, William Pope L., Tehching Hsieh, Revered Billy, Nao Bustamante, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Adrian Piper, Sophie Calle, Ron Athey, Patty Chang, James Luna, and the work of many other body artists/performance artists. Students will develop 1 performance action a week, for 5 weeks, for a total of 5 gestures/actions (during the first part of the class), individually or in collaboration with other students. -

Re-Constructing Performance Art Processes and Practices of Historicisation, Documentation, and Representation (1960S – 1970S)

INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM Re-Constructing Performance Art Processes and Practices of Historicisation, Documentation, and Representation (1960s – 1970s) BOOK OF ABSTRACTS © 2018 Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence Philip Auslander Performance Documentation and Its Discontents; or, Does It Matter Whether or Not It Really Happened? It has become commonplace to assert that performances, as live events, cannot be adequately documented, or cannot be documented at all, or that performance documentation is at least highly problem- atic. Many critiques of performance documentation are premised on the belief that ephem- erality is the key defining characteristic of performance – that it is in performance’s nature to disappear and that to force it to remain through reproduction is to violate its very being. My approach to performance documentation is chiefly pragmatic. It is quite obvious to me that we regularly rely on documentation of one sort or another to give us a sense of perfor- mances that are not immediately available to us in live form. While I certainly recognise that the experience I can obtain from this record is not the same experience I would have had by participating in a live event, I still understand it as an experience of the performance. I do not carefully frame the experience of examining a performance document as an experience of the document only, to be understood as separate from and not necessarily related to an experience of the performance itself. If anything, I operate on the assumption that one can gain usable information about a performance and come to a valid understanding of it on the basis of its documentation. -

ON PAIN in PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das

BEARING WITNESS: ON PAIN IN PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Geography Royal Holloway, University of London, 2016 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Jareh Das hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 19th December 2016 2 Acknowledgments This thesis is the result of the generosity of the artists, Ron Athey, Martin O’Brien and Ulay. They, who all continue to create genre-bending and deeply moving works that allow for multiple readings of the body as it continues to evolve alongside all sort of cultural, technological, social, and political shifts. I have numerous friends, family (Das and Krys), colleagues and acQuaintances to thank all at different stages but here, I will mention a few who have been instrumental to this process – Deniz Unal, Joanna Reynolds, Adia Sowho, Emmanuel Balogun, Cleo Joseph, Amanprit Sandhu, Irina Stark, Denise Kwan, Kirsty Buchanan, Samantha Astic, Samantha Sweeting, Ali McGlip, Nina Valjarevic, Sara Naim, Grace Morgan Pardo, Ana Francisca Amaral, Anna Maria Pinaka, Kim Cowans, Rebecca Bligh, Sebastian Kozak and Sabrina Grimwood. They helped me through the most difficult parts of this thesis, and some were instrumental in the editing of this text. (Jo, Emmanuel, Anna Maria, Grace, Deniz, Kirsty and Ali) and even encouraged my initial application (Sabrina and Rebecca). I must add that without the supervision and support of Professor Harriet Hawkins, this thesis would not have been completed. -

Aalborg Universitet Rhythms Now Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis

Aalborg Universitet Rhythms Now Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited Christiansen, Steen Ledet; Gebauer, Mirjam Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Christiansen, S. L., & Gebauer, M. (Eds.) (2019). Rhythms Now: Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited. (Open Access ed.) Aalborg Universitetsforlag. Interdisciplinære kulturstudier General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: October 05, 2021 Edited by Steen Ledet Christiansen & Mirjam Gebauer Edited by Steen Ledet Christiansen & Mirjam Gebauer RHYTHMS NOW Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited AALBORG UNIVERSITETSFORLAG -

Traditional Narratives and Sculptural Forms: Translating Narratives Into Material Expressions

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 2017+ University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2017 Traditional Narratives and Sculptural Forms: Translating Narratives into Material Expressions Kathleen Stehr University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1 University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Stehr, Kathleen, Traditional Narratives and Sculptural Forms: Translating Narratives into Material Expressions, Masters of Philosophy (Research) thesis, School of the Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2017. -

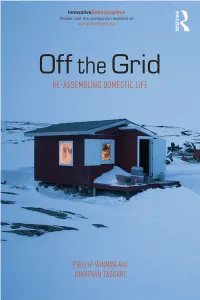

Off the Grid

Off the Grid Off-grid isn’t a state of mind. It isn’t about someone being out of touch, about a place that is hard to get to, or about a weekend spent offline. Off-grid is the property of a building (generally a home but sometimes even a whole town) that is disconnected from the electricity and the natural gas grid. To live off- grid, therefore, means having to radically re-invent domestic life as we know it, and this is what this book is about: individuals and families who have chosen to live in that dramatically innovative, but also quite old, way of life. This ethnography explores the day-to-day existence of people living off- the-grid in each Canadian province and territory. Vannini and Taggart demonstrate how a variety of people, all with different environmental con- straints, live away from contemporary civilization. The authors also raise important questions about our social future and whether off-grid living cre- ates an environmentally and culturally sustainable lifestyle practice. These homes are experimental labs for our collective future, an intimate look into unusual contemporary domestic lives, and a call to the rest of us leading ordinary lives to examine what we take for granted. This book is ideal for courses on the environment and sustainability as well as introduction to sociology and introduction to cultural anthropology courses. Visit www.lifeoffgrid.ca, for resources, including photos of Vannini and Taggart’s ethnographic work. Phillip Vannini is Canada Research Chair in Public Ethnography and Professor in the School of Communication & Culture at Royal Roads University in Victoria, BC, Canada. -

Aalborg Universitet Mapping Wild Rhythms Robert

Aalborg Universitet Mapping Wild Rhythms Robert Macfarlane as Rhythmanalyst Kirk, Jens Published in: Rhythms Now Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Kirk, J. (2019). Mapping Wild Rhythms: Robert Macfarlane as Rhythmanalyst. In S. L. Christiansen, & M. Gebauer (Eds.), Rhythms Now: Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis Revisited (pp. 127-141). Aalborg Universitetsforlag. Interdisciplinære kulturstudier General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: November 25, 2020 Aalborg Universitet Rhythms Now Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited Christiansen, Steen Ledet; Gebauer, Mirjam Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Christiansen, S.