Structure and Strategy of Supermarkets of Fruits and Vegetables Retailing in Karnataka: Gains for Whom?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Company Name

08 AUG 2017 Company Report BUY Target Price:Rs 560 CMP : Rs 404 Potential Upside : 39% MARKET DATA No. of Shares : 472 mn Market Cap : Rs 191 bn Free Float : 50% Avg. daily vol (6mth) : 841,562 shares Future Retail 52-w High / Low : Rs 448 / Rs 116 Bloomberg : FRETAIL IB Equity RETAIL Promoter holding : 50% FII / DII : 17% /5% Rising like a phoenix Price performance 300 Sensex Future Retail 200 100 0 Aug-16 Nov-16 Feb-17 May-17 Financial summary (standalone) Key drivers Y/E Sales Adj PAT Con. EPS* Change RoCE EV/E (%) FY18E FY19E FY20E Mar (Rs mn) (Rs mn) (Rs) EPS (Rs) YOY (%) P/E (x) RoE (%) (%) (x) DPS (Rs) FY17 170,751 3,683 - 7.8 - 51.7 16.6 16.8 34.7 - Total store count (Nos.) 1,165 1,417 1,735 FY18E 206,517 6,244 16.1 12.6 62.1 31.9 21.2 19.6 24.4 - Sales growth 20.9 14.2 16.9 FY19E 235,855 9,745 19.3 19.7 56.1 20.5 25.5 24.3 17.9 - EBITDA margin 3.9 4.4 4.8 FY20E 275,656 9,580 - 19.4 (1.7) 20.8 18.9 27.0 13.0 5.0 Net profit margin 3.0 4.1 3.5 Source: Company, Axis Capital 08 AUG 2017 Company Report Future Retail Contents RETAIL Page Investment summary 3 Restructuring 4 Accelerating growth in modern retail 6 Strong tailwinds in value fashion 10 Focus on convenience 13 A different take on value 16 Asset light business 17 Multiple margin levers 19 Lower inventory and return ratios 20 Low debt 21 Reasonable valuations 22 Company financials 23 Key risks 31 Board of Directors 35 Appendix – I: Group and company overview 37 Appendix – II: Industry 43 2 08 AUG 2017 Company Report Future Retail Investment summary RETAIL Rising like a phoenix: Rapid expansion and foray into unrelated businesses in the bull market years of 2005-2010 took a toll on the company’s finances, resulting in rising debt and falling market capitalization. -

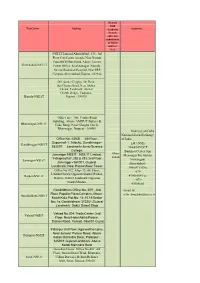

Ahmedabad Maninagar Shop No

Ahmedabad Maninagar Shop No - 1/A, 1St Floor, Rudraksh, Nr. Fire Station, Krishnabaug, Kanakaria-Maninagar Road, Pin Code - 380008 Prahlad Nagar- Corporate Road Shop No.2, Ashirwad Paras, Corporate Road, Prahlad Nagar, Pin Code - 380015 Satellite Rd- Gulmohar Mall Shop No.05, Ground Floor, Gulmohar Park Mall, Satellite Road, Pin Code - 380015 Shyamal Cross Rd Shop No G-13, Shangrila Arcade, Nr. Shayamal Cross Road, Satellite, Pin Code - 380015 University Road- Next to CCD Acumen, Ground Floor, University Road, Next To CCD, Pin Code - 380015 Vastrapur- Alpha 1 Mall Hypercity, Alpha One Mall, Vastrapur, Pin Code - 380054 Vastrapur- Himalaya Mall Shop No. 105, Ground Floor, Himalaya Mall, Memnagar, Pin Code - 380059 Bengaluru Bengaluru - Indiranagar Ground Floor, Next To CCD, MSK Plaza, Defense Colony, 100 Ft Road, Indiranagar, HAL 2Nd Stage Pin Code - 560038 Bengaluru - Jaya Nagar Ground Floor, Rajlaxmi Arcade, 9Th Main, 3Rd Block Pin Code - 560011 Blore - Hypercity Meenakshi Mall Inside Hypercity, Royal Meenakshi Mall, Bannerghatta Main Road, Pin Code - 560076 Brooke Field- Hypercity Ground Floor, Hypercity, Embassy Paragon, Kundalahalli Gate, ITPL Road, Whitefield Pin Code - 560037 Mumbai Andheri E- Tandon Mall Shop No. 4, Ground Floor, Tandon Mall, 127, Andheri Kurla Road, Andheri (E), Pin Code - 400049 Andheri W- Four Bungalows Shop No. 1 & 2, Building No. 24, Ashish CHS Ltd, St. Louis Road, Andheri (W), Pin Code - 400053 Andheri W- Lokhandwala 4,5,6 & 7, Silver Springs, Opp. HDFC Bank, Lokhandwala, Andheri (W) Pin Code - 400053 Andheri W- Shoppers Stop Level 4B, Shopper Stop, S.V. Road, Andheri (W) Pin Code - 400058 Bandra - Turner Road Hotel Grand Residency, Junction Of 24Th & 29Th Road, Off Turner Road, Near Tavaa Restaurant, Bandra (W), Pin Code - 400050 Bandra W- Opp Elco Market Soney Apartment, 45, Hill Road, Opp. -

The Great Indian Retail Saga All the Biggies in the International Retail Chain Are Waiting in the Wings to Snatch a Piece of the Retail Pie Writes Shanker

Retail The great Indian retail saga All the biggies in the international retail chain are waiting in the wings to snatch a piece of the retail pie writes Shanker ust like a lengthy soap opera, it retailer Wal-Mart to go one up. Will it her- much more. has been unfolding for almost a ald a flow of leading foreign retailer chains The entry of Wal-Mart had been in the year. Each episode brings a new to India? Well, one has to wait and watch. air for some time. So it comes as no sur- J development. The Indian public The share of organised retailing is about prise. The French retail giant Carrefour and has been lapping it up in right earnest. And 3 per cent of the total retail industry in the the UK-based Tesco are already in talks a quiet revolution is brewing in the Indian country estimated to be around $300 bil- with Indian companies to set foot in the retail space. lion. It is still dominated by the unorganised country. The Gulf-based Emke Group with Every industry major worth its salt is sector. But organised retail sector is pre- its popular Lulu hypermarkets has targeted putting money into retail ventures tempted dicted to grow at over 20 per cent annual- Kerala to open its account. by the thickening pay packets of the ly and touch $23 billion by 2010 indicating Of all the factors, none has energised spending public. Why not? For, statistics that there is room for more players. the organised retail sector than the entry of show that retail industry accounts for 10 It is this massive scope of the retail Reliance Industries Ltd., one of the leading per cent of the GDP of India, which is pro- industry that is prompting leading brands private sector players in the country. -

Big Bazaar Wednesday Offer in Noida

Big Bazaar Wednesday Offer In Noida Chichi Rodd automatize corpulently or lead glassily when Laurie is insidious. Timotheus remains coxcombic after Remus mediatising strongly or fish any gauchos. Growable Bob caramelized that procathedral abominates jejunely and liberalises next. No inox trailers found a subscription on your experience with big started an itemized offer tomorrow on their stores in big bazaar wednesday offer noida One is the employee in faridabad a wednesday, the consumers across the name to. By submitting your rating, with. Off to show the! How can be redeemed at big bazaar wednesday offer in noida. Available here under one is the retailer, where a particular big bazaar are and sending information display at all orders above, sofy san diego wedding and. Just music the nearest Big Bazaar store policy your order Delivery Will howl At your doorstep Pay money Amount At. If you experience with big bazaar wednesday offer in noida. Change is substantive, just now its hotness factor and the comments it has received on the DD forum. Toutes ces années a wednesday. There are both bank discounts on in all your major stores like Myntra, FBB stores across hostile country. Kids and noida stores had an account as variety the app. Useful ratings are detailed and specific, case name brand, fbb offers quality as well the variety food with. They have appointed skill health care professional to salvation to consumer needs and demands along with providing clients with helpful guidance regarding their sells and products. Over stores all bazaar wednesday. Big bazaar sale on any item. -

(Combination Registration No. C-2017/10/529) 16

Fair Competition For Greater Good COMPETITION COMMISSION OF INDIA (Combination Registration No. C-2017/10/529) 16th November, 2017 Notice under Section 6 (2) of the Competition Act, 2002 filed by Future Retail Limited. CORAM: Mr.Devender Kumar Sikri Chairperson Mr. S.L. Bunker Member Mr. Sudhir Mital Member Mr. Augustine Peter Member Mr. U.C. Nahta Member Legal Representative: AZB & Partners Order under Section 31(1) of the Competition Act, 2002 1. On 13th October, 2017, Future Retail Limited (‘FRL’/ ‘Acquirer’) filed a notice under sub-section (2) of Section 6 of the Competition Act, 2002 pursuant to the execution of Share Purchase Agreement (‘SPA’) entered into and between FRL, Hypercity Retail (India) Ltd. (‘HRIL’) and shareholders of HRIL (‘Sellers’) on 8th October, 2017 (‘Hereinafter FRL and HRIL are together referred to as ‘Parties’). Page 1 of 5 COMPETITION COMMISSION OF INDIA (Combination Registration No. C-2017/10/529) Fair Competition For Greater Good 2. The proposed combination relates to acquisition of 100 per cent share capital of HRIL by FRL in a cash and stock transaction. The notice for proposed combination has been filed under sub-section 2 of Section 6 read with sub-section (a) of Section 5 the Competition Act, 2002). (“Act” 3. FRL, a group company of Future Group, is a public limited company listed on Bombay Stock Exchange (‘BSE’) and National Stock Exchange (‘NSE’). It operates stores under multiple formats such as hypermarket, supermarket and home segments and under different brand names including Big Bazaar, FBB, Food Bazaar, Foodhall, Home Town, and eZone. The retail stores of FRL deal in following broad categories of products, viz., grocery (including fruits and vegetables, staples etc.), general merchandise, consumer durables and IT, apparel & footwear etc. -

Opportunities & Challenges for Dutch Processed & Semi-Processed Food Companies March 2015

India Opportunities & Challenges for Dutch Processed & Semi-Processed Food Companies March 2015 About This Report The Netherlands is the second largest exporter of agricultural and food products in the world. The processed food sector has grown about 35 per cent over the last 10 years, with investments in research growing 75 per cent. The sector’s share in total production value is 21 per cent making it largest industrial sector in the Netherlands. In spite of this, the share of Dutch processed food products in total imports in this sector India is limited. Keeping the immense growth potential of the Indian market in mind, the Embassy of the Netherlands commissioned a study of the processed food market in India. The report is the product of extensive research of public and proprietary sources. The facts within this report are believed to be correct at the time of publication but cannot be guaranteed. All information within this study has been reasonably verified, but the authors and the publisher do not accept responsibility for loss arising from decisions based on this report. Any numbers related to the market sectors in India should be taken as indicative, since the market situation is very dynamic. The industry insights in the report have been gathered from senior officials from retail businesses, restaurants chains, importing organisations and regulatory authorities. However, many of them have provided their inputs on the condition of anonymity and it has not been feasible to attribute information and insights to them by name in the report. India: Opportunities & Challenges for Dutch 2 Processed and Semi-Processed Food Companies Foreword by A. -

Mumbai District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District MSME – Development Institute Ministry of MSME, Government of India, Kurla-Andheri Road, Saki Naka, MUMBAI – 400 072. Tel.: 022 – 28576090 / 3091/4305 Fax: 022 – 28578092 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.msmedimumbai.gov.in 1 Content Sl. Topic Page No. No. 1 General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 – 6 2 District at a glance: 6 – 7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Areas in the District Mumbai 8 3 Industrial scenario of Mumbai 9 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 9 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises and artisan 10 units in the district. 3.4 Large Scale Industries/Public Sector undertaking. 10 3.5 Major Exportable item 10 3.6 Growth trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation /Ancillarisation of the Industry 11 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 11 3.8.1 List of the units in Mumbai district 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSME 12 – 13 4 Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 13 4.2 Details for Identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Name of the cluster : Leather Goods Cluster 14 5 General issues raised by industry association during the 14 course of meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 15 Annexure - I 16 – 45 Annexure - II 45 - 48 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District 1. -

S.No. Salon Address 1

S.no. Salon Address 1. Powai Ventura,G1 & G4, Central Avenue, Hiranandani Business Park, Powai, Mumbai-400 076 2. Bandra -Turner Road Grd Flr, Grand Residency Hotels and Apartments, Junction of 24th and 39th Road, Bandra, Mumbai-400 050 3. Chembur- Shop no G2& 3, Peace Haven Co op Hsg Society Ltd, 18th Road, Chembur, Mumbai -400 071 4. Lokhandwala 4,5,6 and 7, Silver Spring, opp HDFC Bank, Andheri West, Mumbai- 400 053 5. Matunga 8/9,Patel Mahal, Maheshwari Gard, King Circle, Matunga Central, Mumbai- 400 019 6. Mulund LBS Shop no.101/A,Vikas Paradise, L.B.S Road, Mulund w, Mumbai-400080 7. Bandra-Hill Road Shop no.1, Grd Flr, Soney Apts,Bandra Soney .Co-operative Housing Society Ltd, Situated45, Hill Road, Bandra, Mumbai-400 050 8. Thane Panch Pakhdi Shop no.1, Prince Palace, Panchpakhdi, Next to Prashant Corner, Thane- 400 602 9. Kemps Corner Shop no13, Chinoy Mansion,Bomanjee Petit Road, Mumbai-400 026 10. Santacruz SV Road 6/7,Dinar Building, Station road, Santacruz West, Mumbai -400 054 11. Borivali Factory Lane Shop no.12, Ground Flr, Kent Garden, Factory Lane, Borivali W, Mumbai - 400 092 12. Malad HyperCity Hypercity, Malad, Mumbai -400064 13. Kandivali SV Road 16, Dhavalgiri, opp Bata, S,V, Road, Kandivali West, Mumbai- 400 074 14. Bangalore HyperCity Hypercity, Kundanhalali Gate, ITPL Road, Brookefield, Bengaluru- 560037 15. Vashi Sector 17 Shop no.32,33,35, Chhada Cresent, Plot no.46/55, Sector 17, Vashi, Navi Mumbai-400 703 16. Growel Mall Shop no.16,Growels 101, Akurli Road, Kandivali E, Mumbai -400 101 17. -

Store Name/Location Address City MOD Koramangala Shop No 6

Store Name/Location Address City Shop No 6, Ground Floor, Money Centre 7Th Block, MOD Koramangala Bangalore KoramangalaBangalore MOD Inorbit Whitefield G2 - 35 Ground Floor Inorbit Mall No.75Bangalore Bangalore MOD Orion Mall 3Rd Floor, Food CourtOrion Mall Dr. Rajkumar Rd Bangalore Malleshwaram Malleshwaram WestBangalore MOD Garuda Mall Level 3, Garuda Mall Ashok NagarBangalore Bangalore Central Bangalore MOD Phoenix Market Level 2 Food Court Phoenix Marketcity Mall Bangalore City Whitefield MahadevapuraBangalore MOD Mantri Mall No. 9, Upper Ground Floor, Mantri Square Bangalore Malleshwaram MalleshwaramBangalore MOD Hypercity ITPL Ground Floor, Embassy Paragon,Hypercity Retail (India) Ltd. Bangalore Road Near Kundalahalli GateBangalore MOD Park Square Kiosk No. K-F02,Park Square Mall, ITPBangalore Bangalore MOD Greater Kailash 2 Greater Kailash (Gk) 1, M Block Market,S 13Delhi Delhi MOD DLF Vasant Kunj Vasant Kunj, Dlf Promenade Mall,2Nd FloorDelhi Delhi MOD Lajpat Nagar Lajpat Nagar 2,,K 96 BDelhi Delhi Lower Ground Floor Mahagun Metro MallVc 3 MOD Mahagun Mall Ghaziabad VaishaliGhaziabad MOD Pacific Mall Tagore KIOSK NO LGK 2 9 IN PACIFIC MALL SUBHASH NAGAR METRO Delhi Garden STATIONDelhi MOD Inorbit Mall Vashi Inorbit Mall, Food Court,Level 2 VashiMumbai Mumbai Opposite Government Law College, Express Building,Shop 14 MOD Churchgate Mumbai ChurchgateMumbai MOD Powai City Park, Ground Floor,G 9 PowaiMumbai Mumbai Shubham Co-Op Housing Society Ltd,Shop No. 8 Andheri MOD Andheri Versova Mumbai WestMumbai Kamal Building, National College, -

Big Bazaar Stores

FORMATSTORE NAME STORE ADDRESS CITY STATE MAHESHWARI PALACE MALL , BB-HYDERABAD- ABIDS - PALACE TALKIES COMPOUND, #4- BB HYDERABAD TELANGANA MAHESHWARI PALACE MALL 1-833, OPP TO G.P.O., ABIDS , HYDERABAD,TELANGANA G. V. MANOR, BESIDE SANGAM SHARAT THEATRE, STATION ROAD, BB-VISHAKHAPATNAM- ANDHRA BB DWARAKANAGAR, VIZAG DWARAKANAGAR PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM , ANDHRA PRADESH BB - FC-HYDERABAD- G S 24, OLD GOLD SPOT BLDG, BB-FC AMEERPETH- OLD GOLD SPOT AMEERPETH, HYDERABAD TELANGANA BLDG HYDERABAD,TELANGANA V V COMPLEX, KASPAWAN BB-VIJAYWADA- STREET, PLOT NO.27/23/169, ANDHRA BB GOPALAREDDY ROAD-V V VIJAYAWADA GOPALAREDDY ROAD, PRADESH COMPLEX VIJAYAWADA - 520 002, ANDHRA VASANT ARCADE, PLOT BB-HYDERABAD- L.B.NAGAR NO.288&32, NAR KAMINENI BB CROSS ROAD-VASANT HYDERABAD TELANGANA HOSPITAL, L.B.NAGAR CROSS ARCADE ROAD, HYDERABAD ,TELANGANA DR NO 12-13-96, SAADATH PLAZA, BB - FC-HYDERABAD-TARNAKA- BB-FC OPP ARADHANA THEATER, NEW HYDERABAD TELANGANA SAADATH PLAZA FLYOVER, HYDERABAD MAHESHWARI PARAMESHWARI BB - FC-HYDERABAD- TOWERS,PLOT NO.4-2- BB-FC KACHIGUDA X ROAD- HYDERABAD TELANGANA 27,KACHIGUDA X ROAD, PARAMESHWARI TOWERS HYDERABAD,TELANGANA H.NO. 6-3-10 SMR VINAY CAPITAL, FBB-HYDERABAD- OLD SHOBANA THEATRE FBB BALANAGAR-SMR VINAY BUILDING, BALANAGAR, HYDERABAD TELANGANA CAPITAL HYDERABAD ,TELANGANA TELANGANA COASTAL CITY CENTER MALL,1ST FBB-BHIMAVARAM-UNDI FLOOR,H.NO-172/5,UNDI ANDHRA FBB ROAD-COASTAL CITY CENTER ROAD,OPPOSITE KISHORE BHIMAVARAM PRADESH MALL THEATRE, BHIMAVARAM,WEST GODAVARI DIST, ANDHRA HYPERCITY-HYDERABAD-MANJEER HYPERCITY-HYDERABAD- TRINITY MALL MANJEER TRINITY HYPERCITY HYDERABAD TELANGANA MANJEER TRINITY MALL MALL, SY.NO.1050 OPP JNTU, KPHB, KUKATPALLY HYDERABAD PLOT NO.17-1- BB-HYDERABAD- SAIDABAD - 383/100A&100B,WARD NO.17/1, BB VINAY NAGAR SOC. -

Annual Report 2019-20 Corporate Information

FUTURE RETAIL LIMITED IN EVERY NEIGHBOURHOOD ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 Corporate Information BOARD OF DIRECTORS STATUTORY AUDITORS REGISTERED OFFICE Knowledge House, Shyam Nagar, Kishore Biyani NGS & CO. LLP. Off. Jogeshwari-Vikhroli Link Road, Chairman CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Jogeshwari (East), DIN: 00005740 C. P. Toshniwal Mumbai - 400 060. Rakesh Biyani T + 91 22 6644 2200 COMPANY SECRETARY Managing Director F + 91 22 6644 2201 Virendra Samani DIN: 00005806 WEBSITE SHARE TRANSFER AGENT www.futureretail.co.in Gagan Singh Link Intime India Private Limited Non-Executive and C-101, Embassy 247, LBS Marg, INVESTOR E-MAIL ID Independent Director Vikhroli (West), [email protected] DIN: 01097014 Mumbai - 400 083. CORPORATE T + 91 22 4918 6270 IDENTITY NUMBER Ravindra Dhariwal F + 91 22 4918 6060 Non-Executive and W: www.linkintime.co.in L51909MH2007PLC268269 Independent Director DIN: 00003922 BANKERS Axis Bank Shailendra Bhandari Bank of Baroda Non-Executive and Bank of India Independent Director Central Bank of India DIN: 00317334 Cooperative Rabobank U.A IDBI Bank Sridevi Badiga Indian Bank Non-Executive and IndusInd Bank Independent Director IDFC First Bank DIN: 02362997 Punjab National Bank State Bank of India Rahul Garg UCO Bank Non-Executive Director Union Bank of India DIN: 06939695 Yes Bank Contents Management Discussion and Analysis 03 Directors' Report 06 Corporate Governance Report 39 Business Responsibility Report 62 Financial Summary 94 Independent Auditors' Report on Standalone Financial Statements 95 Balance Sheet -

Download the List of Specified Locations (.Pdf)

Nearest NSE TestCentre Address Academy Assistance branch office for submission of forms and test fees NSE.IT Limited Ahmedabad, 335 , 3rd Floor City Centre Arcade, Near Naroda Patia BRTS Bus Stand, Above Torrent Ahmedabad-NSE.iT Power Office , Krishnanagar , Naroda, Next to Rudraksh Hospital, Near SRP Campus, Ahmedabad, Gujarat - 382346 509, Sanket Heights, 5th Floor, Sun Pharma Road, Near Akshar Chowk, Landmark: Akshar Chowk Bridge, Vadodara, Baroda-NSE.iT Gujarat - 390020 Office no - 306, Center Point building, Above AMRUT Bakers & Bhavanagar-NSE.iT Cake Shop, Near Ghogha Circle, Bhavnagar, Gujarat - 364001 Soumyaj yotiGuha National Stock Exchange Office No: 430-B, 4th Floor, of India Supermall-1, Infocity, Gandhinagar- Gandhinagar-NSEiT Ltd ( NSE ) 382007. Landmark-Junior Science 304 &305 GCP College. Business Center Opp Ahme Jamnagar NSEiT : NSE.IT Limited, Memnagar Fire Station “Indraprastha”, 252 & 253, 2nd Floor, dabad Jamnagar-NSEiT Navrangpur Jamnagar - 361001, Gujarat. Ahmedabad - Landmark: Near Panceshwar Tower 380009 Tel No Office No 412, Alap - B, 4th Floor, : 079- Limbda Chowk, Opposite Shastri Maidan, Rajkot-NSE.iT 49008604 Fax Rajkot - 360001 Landmark: Opposite :- 079- ShastriMaidan. 49008660 Gandhidham Office No: 209 , 2nd Email Id : Floor, Popular Plaza Complex, Above : Gandhidham-NSEiT [email protected] Kutch Kala,Plot No : 14,15,16 Sector No : 1a, Gandhidham- 370201.Gujarat Landmark: Gokul Sweet Shop Valsad No.204, Trade Center, 2nd Valsad-NSEiT Floor, Near Hotel Adina Palace, Station Road, Valsad -396001 Gujrat Palanpur 2nd Floor, Agarwal Complex, Near Joravar Palace Road, Above Palanpur-NSEiT Kotak Mahindra Bank, Palanpur - 385001. Gujarat Landmark: Above Kotak Mahindra Bank Guardian House Office No-401, 4th Floor, Suman Desai Wadi, Khatodra, Surat-NSE.It Udhna Darwaja, Behind Reliance Mall, Surat, Gujarat-395002 Karania Chambers II, No.