Bovington Garrison & the Armour Centre: a History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Frome 8, Piddle Catchmentmanagement Plan 88 Consultation Report

N 6 L A “ S o u t h THE FROME 8, PIDDLE CATCHMENTMANAGEMENT PLAN 88 CONSULTATION REPORT rsfe ENVIRONMENT AGENCY NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House. Goldhay Way. Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR NRA National Rivers Authority South Western Region M arch 1995 NRA Copyright Waiver This report is intended to be used widely and may be quoted, copied or reproduced in any way, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and that due acknowledgement is given to the National Rivers Authority. Published March 1995 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Hill IIII llll 038007 FROME & PIDDLE CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT YOUR VIEWS The Frome & Piddle is the second Catchment Management Plan (CMP) produced by the South Wessex Area of the National Rivers Authority (NRA). CMPs will be produced for all catchments in England and Wales by 1998. Public consultation is an important part of preparing the CMP, and allows people who live in or use the catchment to have a say in the development of NRA plans and work programmes. This Consultation Report is our initial view of the issues facing the catchment. We would welcome your ideas on the future management of this catchment: • Hdve we identified all the issues ? • Have we identified all the options for solutions ? • Have you any comments on the issues and options listed ? • Do you have any other information or ideas which you would like to bring to our attention? This document includes relevant information about the catchment and lists the issues we have identified and which need to be addressed. -

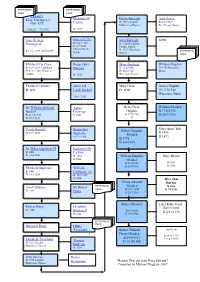

Meaden Descent from King Edward I Compiled by Michael Dugdale

EXTENDED EXTENDED TREE TREE Edward I Eleanore Of Henry Burleigh Amy Sexey King Plantagenet B: 1619 Langton B: 26/8/1627 1216 - 1272 Castile Maltravers, Dorset Bere Regis, Dorset. 17/6/1239 – 7/7/1307 D: 1290 Joan Of Acre Gilbert (Sir) The John Burleigh JANE Red De Clare Plantagenet B: 3/1654 Turners B: 2/9/1243. Puddle, Dorset Christ Church, B:1272. Acre ‘Holy Land’ D: 1727, Wareham Hants EXTENDED Dorset TREE Elizabeth De Clare Roger (Sir) Mary Burleigh William Dugdale B: 16/9/1295 Tewksbury Damory B: 11/4/1690 D: 1756 Wareham, D: 4?11/1360. Minories, D: 24/8/1766 Dorset Aldgate D: 1322 Wareham, Dorset Elizabeth Damory John (3rd Mary Dean Daniel Dugdale B: 1318 Lord) Bardolf D: 1800 D:17/3/1782 Wareham, Baker 1350 - 1363 Sir William 4th Lord Agnes Betty Dean William Meaden Bardolf Poynings Dugdale B 17/8/1756 B: 21/10/1349 D:1403 B 11/3/1766 D 30/9/1796 D: 29/1/1385 D Cecily Bardolf Brian (Sir) Mary Ann Clark Robert Dugdale D: 29/9/1432 B 1805 Stapleton Meaden 1377 - 1438 D 1892 B 1795 D 6/4/1845 Sir Miles Stapleton VI Katherine De B: 1408 La Pole D: 1/10/1466 B: 1416 William Dugdale Mary Brown D:1488 Meaden B 2/12/1828 B 1831 D 26/9/1903 D 1906 Elizabeth Stapleton William B: 1441 Calthorpe VII D: 18/2/1504 B: 30/1/1409 D:1494 Alice Jane Henry Edward Burton Ann Calthorpe Sir Robert EXTENDED Meaden B 1854 TREE B 22/1/ 1854 D 7/8/1923 D: 1494 Drury D 23/3/1918 Robert Meaden Ethel Ruby Good Robert Drury Elizabeth 2 B29/9/1890 D: 1589 Brudenell B 8/3/1884 D 8/11/1948 D:1542 D 29/9/1945 E XTENDED TREE Margaret Drury Henry Trenchard Robert William Ivy Wells Henry Meaden B 24/11/1913 Elizabeth Trenchard B 24/4/1912 D 14/3/1995 Thomas D 13 /4/1988 D: 1627 Lytchett Burleigh Maltravers, Dorset B: 1558 Henry Burleigh Hester B: 1590 Langton Heybourne Meaden Descent from King Edward I Maltravers, Dorset Compiled by Michael Dugdale. -

Piddle Valley Conservation Area Review

Item 14 Council Meeting – 16 January 2018 Piddle Valley Conservation Area review 1. Purpose of report The purpose of this report is to seek the Council’s approval to adopt the draft appraisal and boundary proposal prepared for Piddle Valley Conservation Area. 2. Key issues 2.1 The Council designates and reviews conservation areas in fulfilment of statutory duties under Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. Purbeck District has twenty five Conservation Areas, twenty-two of which have been appraised and reviewed since their designation, twenty-one of these since 2008. 2.2 A conservation area is a historic built environment designation. The designation promotes the preservation and enhancement of groups of buildings and structures which hold special historic or architectural interest, together with associated spaces and trees. This is primarily achieved through the sensitive management of change within the planning process. 2.3 Paragraph 127 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) highlights the importance of ensuring that conservation area designations are justified. This is the key objective of the boundary review, and ensures fairness in the application of controls, and soundness in case of appeal against planning decisions. 2.4 The Council has a statutory duty to consider the impact of planning proposals upon conservation areas. This is reflected in paragraph 129 of the NPPF, which requires local planning authorities to assess the significance of heritage assets as part of the development management process. Assessment of significance is a key objective of conservation area character appraisals, and therefore provides the Council with an important part of the required evidence base in decision making. -

MOIGNE COMBE ESTATE Dorchester • Dorset • DT2 8JA

MOIGNE COMBE ESTATE Dorchester • Dorset • DT2 8JA MOIGNE COMBE ESTATE Dorchester • Dorset • DT2 8JA Moreton railway station (London Waterloo 2 hrs 54 mins) – 1.5 miles Dorchester – 6 miles • The coast at Ringstead Bay – 8 miles Bournemouth – 25 miles Southampton Airport – 52 miles • London – 125 miles (Distances and times approximate) A Charming Compact Amenity Estate With Impressive Principal Residence 10 bedroom principal house in need of modernisation Separate detached former Stable House with walled garden An attractive let farm with period farmhouse Private and secluded location A pair of let cottages Attractive woodlands, grazing and lakes Additional cottages available by separate negotiation Available as a whole or in 4 Lots In all about 140 acres Wimborne Salisbury Wessex House, Priors Walk Rolfes House, 60 Milford Street Wimborne BH21 1PB Salisbury SP1 2BP Contact: Ashley Rawlings Contact: George Syrett Tel: 01202 856800 Tel: 01722 426810 [email protected] [email protected] savills.co.uk Introduction The Moigne Combe Estate was purchased prior to 1895 by Harry Pomeroy Bond and Moigne Combe House was then built in 1900. After the War Office requisitioned their principal home and Estate at Tyneham for the War effort in 1943, Ralph & Evelyn Bond moved to Moigne Combe. Following his retirement from the Army in 1972, their son, Major-General Mark Bond took over the running of the Estate and pursued an active public life. He lived there happily, surrounded by the Moigne Combe Woods and the tranquillity he loved, until his death in 2017. The Moigne Combe Estate is a privately situated, picturesque estate located just 6 miles from Dorchester, comprising a substantial 10 bedroom manor house, a further four- bedroom detached Stable House and two let cottages. -

The Evolution of British Tactical and Operational Tank Doctrine and Training in the First World War

The evolution of British tactical and operational tank doctrine and training in the First World War PHILIP RICHARD VENTHAM TD BA (Hons.) MA. Thesis submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy by the University of Wolverhampton October 2016 ©Copyright P R Ventham 1 ABSTRACT Tanks were first used in action in September 1916. There had been no previous combat experience on which to base tactical and operational doctrine for the employment of this novel weapon of war. Training of crews and commanders was hampered by lack of vehicles and weapons. Time was short in which to train novice crews. Training facilities were limited. Despite mechanical limitations of the early machines and their vulnerability to adverse ground conditions, the tanks achieved moderate success in their initial actions. Advocates of the tanks, such as Fuller and Elles, worked hard to convince the sceptical of the value of the tank. Two years later, tanks had gained the support of most senior commanders. Doctrine, based on practical combat experience, had evolved both within the Tank Corps and at GHQ and higher command. Despite dramatic improvements in the design, functionality and reliability of the later marks of heavy and medium tanks, they still remained slow and vulnerable to ground conditions and enemy counter-measures. Competing demands for materiel meant there were never enough tanks to replace casualties and meet the demands of formation commanders. This thesis will argue that the somewhat patchy performance of the armoured vehicles in the final months of the war was less a product of poor doctrinal guidance and inadequate training than of an insufficiency of tanks and the difficulties of providing enough tanks in the right locations at the right time to meet the requirements of the manoeuvre battles of the ‘Hundred Days’. -

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY Master's Thesis the M26 Pershing

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY Master’s Thesis The M26 Pershing: America’s Forgotten Tank - Developmental and Combat History Author : Reader : Supervisor : Robert P. Hanger Dr. Christopher J. Smith Dr. David L. Snead A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts In the Liberty University Department of History May 11, 2018 Abstract The M26 tank, nicknamed the “General Pershing,” was the final result of the Ordnance Department’s revolutionary T20 series. It was the only American heavy tank to be fielded during the Second World War. Less is known about this tank, mainly because it entered the war too late and in too few numbers to impact events. However, it proved a sufficient design – capable of going toe-to-toe with vaunted German armor. After the war, American tank development slowed and was reduced mostly to modernization of the M26 and component development. The Korean War created a sudden need for armor and provided the impetus for further development. M26s were rushed to the conflict and demonstrated to be decisive against North Korean armor. Nonetheless, the principle role the tank fulfilled was infantry support. In 1951, the M26 was replaced by its improved derivative, the M46. Its final legacy was that of being the foundation of America’s Cold War tank fleet. Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 1. Development of the T26 …………………………………………………..………..10 Chapter 2. The M26 in Action in World War II …………...…………………………………40 Chapter 3. The Interwar Period ……………………………………………………………….63 Chapter 4. The M26 in Korea ………………………………………………………………….76 The Invasion………………………………………………………...………77 Intervention…………………………………………………………………81 The M26 Enters the War……………………………………………………85 The M26 in the Anti-Tank Role…………………………………………….87 Chapter 5. -

Procurement Politics, Technology Transfer and the Challenges of Collaborative MBT Projects in the NATO Alliance Since 1945

A Standard European Tank? Procurement Politics, Technology Transfer and the Challenges of Collaborative MBT Projects in the NATO Alliance since 1945 Mike Cubbin School of Arts and Media Salford University Submitted to the University of Salford in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 Abstract International cooperation in weapons technology projects has long been a feature of alliance politics; and, there are many advantages to both international technology transfer and standardisation within military alliances. International collaboration between national defence industries has produced successful weapon systems from technologically advanced fighter aircraft to anti-tank missiles. Given the success of many joint defence projects, one unresolved question is why there have been no successful collaborative international main battle tank (MBT) projects since 1945. This thesis seeks to answer this question by considering four case studies of failed attempts to produce an MBT through an international collaborative tank project: first and second, the Franco-German efforts to produce a standard European tank, or Euro-Panzer (represented by two separate projects in 1957-63 and 1977- 83); third, the US-German MBT-70 project (1963-70); and, fourth, the Anglo-German Future Main Battle Tank, or KPz3 (1971-77). In order to provide an explanation of the causes of failure on four separate occasions, the analysis includes reference to other high-technology civilian and military joint projects which either succeeded, -

![[DORSET.] 750 [POST OFFICE • Cerne](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4330/dorset-750-post-office-cerne-1474330.webp)

[DORSET.] 750 [POST OFFICE • Cerne

[DORSET.] 750 [POST OFFICE • Cerne. Totcombe and l\Iodbury:-Cattistock, Cerne Wimborne St. GiJes :-Hampreston, Wimborne St. Giles. Abba!o1, Compton Abbas, Godmanstoue, Hilfield, Nether Winfrith :-Coombe Keynes, East Lulworth, East Stoke, Cerne. Moreton Poxwell, Warmwell, Winfrith Newburgh, Woods- Cogdean :-Canford Magna, Charlton Marshall, Corfe ford. Mullen, Halllworthy, Kinson or Kin~stone, Longfleet, WJke Regis and Elwellliberty :-Wyke Regis. Lytchett Matl'avers, LJtchett l\1inster, Parkstone, 8tur- Yetminster :- Batcomhe, Chetnole, Clifton May bank, minster Marshall. Leigh, Melbury Bllbb, Melbury OSlllond, Yetminster. Coombs Ditch :-Anderilon, Blandford St. Mary, Bland- Bridport borough :-Bridport. ford Forum, Bloxworth, Winterborne Clenstone, Winter- Dorchester borough :-AlI Saints (Dorchester), Holy borne Thomson, Winterborne Whitechurch. Trinity (Dorchester), St. Peter (Dorchester). Corfe Castle :-Corfe Castle. Lyme Regis boroug-h. Cranborne :-Ashmore, Bellehalwell.Cranborne, Edmons- Poole Town and County: -St. James (Poole). ham. Farnham Tollard, Pentridge, Shillingstone or Shilling Shaftesbury borough :-Holy Trinity (Shaftesbury), St. Okeford, Tarrant Gunville, Tarrant Rushton, Turnwortb, James (Shaftesbury), St. Peter (Shaftesbury). West Parley, Witchampton. Wareham borough :-Lady St. Mary (Wareham), St. Culliford Tree:-Broadway, Buckland Ripers, Osmington, Martin (Wareham), The Holy Trinity (Wareham). Radipole, West Chickerell, West Knightoll, West Stafford, Weymouth borough :-Melcombe Regis, Weymouth. Whitcom be, Winterbourne Came, Winterbourne Herring- The old Dorset County Pauper Lunatic Asylum, is situated stone, Winterbourne Moncktoll. at Forston, 2~ miles north-west from Charminster: it fiu- Dewlish liberty :-Dewlish. nishes accommodation for 150 patients: it was formerly the E!!gerton :-Askerswell, Hook, Long Bredy, Poorstock, seat of the late Fl'ancis John Browne, who ~ave it to the Winterbourne Abbas, Wraxall. county for this purpose, and was opened in 1832; it has been FOl'dil1~toll' liberty :-Fordington, Frampton, Hermitage. -

Beacon Ward Beaminster Ward

As at 21 June 2019 For 2 May 2019 Elections Electorate Postal No. No. Percentage Polling District Parish Parliamentary Voters assigned voted at Turnout Comments and suggestions Polling Station Code and Name (Parish Ward) Constituency to station station Initial Consultation ARO Comments received ARO comments and proposals BEACON WARD Ashmore Village Hall, Ashmore BEC1 - Ashmore Ashmore North Dorset 159 23 134 43 32.1% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed Melbury Abbas and Cann Village BEC2 - Cann Cann North Dorset 433 102 539 150 27.8% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed Hall, Melbury Abbas BEC13 - Melbury Melbury Abbas North Dorset 253 46 Abbas Fontmell Magna Village Hall, BEC3 - Compton Compton Abbas North Dorset 182 30 812 318 39.2% Current arrangements adequate – no Fontmell Magna Abbas changes proposed BEC4 - East East Orchard North Dorset 118 32 Orchard BEC6 - Fontmell Fontmell Magna North Dorset 595 86 Magna BEC12 - Margaret Margaret Marsh North Dorset 31 8 Marsh BEC17 - West West Orchard North Dorset 59 6 Orchard East Stour Village Hall, Back Street, BEC5 - Fifehead Fifehead Magdalen North Dorset 86 14 76 21 27.6% This building is also used for Gillingham Current arrangements adequate – no East Stour Magdalen ward changes proposed Manston Village Hall, Manston BEC7 - Hammoon Hammoon North Dorset 37 3 165 53 32.1% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed BEC11 - Manston Manston North Dorset 165 34 Shroton Village Hall, Main Street, BEC8 - Iwerne Iwerne Courtney North Dorset 345 56 281 119 -

Heritage at Risk Register 2012

HERITAGE AT RISK 2012 / SOUTH WEST Contents HERITAGE AT RISK 3 Reducing the risks 7 Publications and guidance 10 THE REGISTER 12 Content and assessment criteria 12 Key to the entries 15 Heritage at risk entries by local planning authority 17 Bath and North East Somerset (UA) 19 Bournemouth (UA) 22 Bristol, City of (UA) 22 Cornwall (UA) 25 Devon 62 Dorset 131 Gloucestershire 173 Isles of Scilly (UA) 188 North Somerset (UA) 192 Plymouth, City of (UA) 193 Poole (UA) 197 Somerset 197 South Gloucestershire (UA) 213 Swindon (UA) 215 Torbay (UA) 218 Wiltshire (UA) 219 Despite the challenges of recession, the number of sites on the Heritage at Risk Register continues to fall. Excluding listed places of worship, for which the survey is still incomplete,1,150 assets have been removed for positive reasons since the Register was launched in 2008.The sites that remain at risk tend to be the more intractable ones where solutions are taking longer to implement. While the overall number of buildings at risk has fallen, the average conservation deficit for each property has increased from £260k (1999) to £370k (2012).We are also seeing a steady increase in the proportion of buildings that are capable of beneficial re-use – those that have become redundant not because of any fundamental lack of potential, but simply as the temporary victims of the current economic climate. The South West headlines for 2012 reveal a mixed picture. We will continue to fund Monument Management It is good news that 8 buildings at risk have been removed Schemes which, with match-funding from local authorities, from the Register; less good that another 15 have had to offer a cost-effective, locally led approach to tackling be added. -

Appendix C(I)

Thriving communities in balance with the natural environment Final Accounts 2018 - 2019 www.dorsetforyou.gov.uk Statement of Accounts 2018/19 Contents Narrative Report Page Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Corporate Strategy 2 3. Council performance 2-4 4. Risk and performance management 4 - 5 5. Financial performance 5-11 6. Economy, efficiency and effectiveness 12 7. Local government reorganisation 12 Statement of Responsibilities 13 Audit Opinion Annual Governance Statement 15-23 12 12 12 Statement of Accounts Section 1- Core Financial Statements Introduction 24 Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement 25 Movement in Reserves Statement 26 Balance Sheet 27-28 Cash Flow Statement 29 Section 2 - Notes to the Core Financial Statements General Notes Note 1 Accounting Standards issued but not yet 30 adopted Note 2 Accounting Policies 30 - 43 General Principles 30 Policy 1 Accounting Estimates 31 Policy 2 Accounting Policy Changes 31 Policy 3 Accruals of Income and Expenditure 31 Policy 4 Business Rates Appeals 31 Policy 5 Cash and Cash Equivalents 32 Policy 6 Contingent Assets and Liabilities 32 Policy 7 Employee Benefits 33 Policy 8 Events After the Balance Sheet Date 34 Policy 9 Financial Instruments 34 Policy 10 Financial Loans 35 Policy 11 Foreign Currency Transactions 35 Policy 12 Government Grants and Contributions 36 Policy 13 Heritage Assets 36 Policy 14 Intangible Assets 36 Contents continued Page Page Policy 15 Inventories and Long Term Contracts 37 Policy 16 Investment Property 37 Policy 17 Leases 37 Policy 18 Non-Current Assets -

Purbeck Forest Plan Affpuddle and Moreton

Purbeck Forest Design Plan Plan Name: Affpuddle & Moreton FOREST ENTERPRISE Application for Forest Design Plan Approvals FE Plan Reference Number: NEW 106 Forest District: South Forest District FC Geographic Block No : 11 Woodland / Property Name: Affpuddle & Moreton Forest Date of Commencement of Plan: 1 August, 2013 FE Reference Number: NEW 106 Approval Period: 1 August 2013 to 31 July 2023 (10 years) Nearest town or village: Bovington Summary of Activity within Approval Period: OS Grid Reference: SY 816 911 (Centre of Site) Local Authority: Purbeck District Council All areas in hectares Activity Conifers Broadleaves Other Heathland Total I apply for Forest Design Plan approval for the property described above and in the enclosed Open or Mire Area Forest Design Plan. Space Felling 96.5 96.5 I undertake to obtain any permissions necessary for the implementation of the approved Restocking 51.4 3.8 55.2 Plan. Other 41.3 41.3 Habitat Restoration Signed: Michael Seddon, Deputy Surveyor, New Forest Total Plan Area: 411 Ha Date: Approved: ...................................................................................... Conservator Conservancy: ............................................................................................................ Date: ...................................................... | Purbeck FDP | May 2013 | Purbeck Forest Design Plan woodland through a programme of phased felling and replanting and the current proposals 7. Affpuddle & Moreton NEW 106 will continue this process. The inclusion of areas of woodland