Network Effects and Legal Citation: How Antitrust Theory Predicts Who Will Build a Better Bluebook Mousetrap in the Age of Electronic Mice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bluebook Citation in Scholarly Legal Writing

BLUEBOOK CITATION IN SCHOLARLY LEGAL WRITING © 2016 The Writing Center at GULC. All Rights Reserved. The writing assignments you receive in 1L Legal Research and Writing or Legal Practice are primarily practice-based documents such as memoranda and briefs, so your experience using the Bluebook as a first year student has likely been limited to the practitioner style of legal writing. When writing scholarly papers and for your law journal, however, you will need to use the Bluebook’s typeface conventions for law review articles. Although answers to all your citation questions can be found in the Bluebook itself, there are some key, but subtle differences between practitioner writing and scholarly writing you should be careful not to overlook. Your first encounter with law review-style citations will probably be the journal Write-On competition at the end of your first year. This guide may help you in the transition from providing Bluebook citations in court documents to doing the same for law review articles, with a focus on the sources that you are likely to encounter in the Write-On competition. 1. Typeface (Rule 2) Most law reviews use the same typeface style, which includes Ordinary Times New Roman, Italics, and SMALL CAPITALS. In court documents, use Ordinary Roman, Italics, and Underlining. Scholarly Writing In scholarly writing footnotes, use Ordinary Roman type for case names in full citations, including in citation sentences contained in footnotes. This typeface is also used in the main text of a document. Use Italics for the short form of case citations. Use Italics for article titles, introductory signals, procedural phrases in case names, and explanatory signals in citations. -

Bluebook & the California Style Manual

4/21/2021 Purposes of Citation 1. To furnish the reader with legal support for an assertion or argument: a) provide information about the weight and persuasiveness of the BLUEBOOK & source; THE CALIFORNIA b) convey the type and degree of support; STYLE MANUAL c) to demonstrate that a position is well supported and researched. 2. To inform the reader where to find the cited authority Do You Know the Difference? if the reader wants to look it up. LSS - Day of Education Adrienne Brungess April 24, 2021 Professor of Lawyering Skills McGeorge School of Law 1 2 Bluebook Parts of the Bluebook 1. Introduction: Overview of the BB 2. Bluepages: Provides guidance for the everyday citation needs of first-year law students, summer associates, law clerks, practicing lawyers, and other legal professionals. Includes Bluepages Tables. Start in the Bluepages. Bluepages run from pp. 3-51. 3. Rules 1-21: Each rule in the Bluepages is a condensed, practitioner-focused version of a rule from the white pages (pp. 53-214). Rules in the Bluepages may be incomplete and may refer you to a rule(s) from the white pages for “more information” or “further guidance.” 4. Tables (1-17): Includes tables T1 – T16. The two tables that you will consult most often are T1 and T6. Tables are not rules themselves; rather, you consult them when a relevant citation rule directs you to do so. 5. Index 6. Back Cover: Quick Reference 3 4 1 4/21/2021 Getting Familiar with the Bluebook Basic Citation Forms 3 ways to In the full citation format that is required when you cite to Common rules include: a given authority for the first time in your document (e.g., present a Lambert v. -

Vol. 123 Style Sheet

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 123 STYLE SHEET The Yale Law Journal follows The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (19th ed. 2010) for citation form and the Chicago Manual of Style (16th ed. 2010) for stylistic matters not addressed by The Bluebook. For the rare situations in which neither of these works covers a particular stylistic matter, we refer to the Government Printing Office (GPO) Style Manual (30th ed. 2008). The Journal’s official reference dictionary is Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. The text of the dictionary is available at www.m-w.com. This Style Sheet codifies Journal-specific guidelines that take precedence over these sources. Rules 1-21 clarify and supplement the citation rules set out in The Bluebook. Rule 22 focuses on recurring matters of style. Rule 1 SR 1.1 String Citations in Textual Sentences 1.1.1 (a)—When parts of a string citation are grammatically integrated into a textual sentence in a footnote (as opposed to being citation clauses or citation sentences grammatically separate from the textual sentence): ● Use semicolons to separate the citations from one another; ● Use an “and” to separate the penultimate and last citations, even where there are only two citations; ● Use textual explanations instead of parenthetical explanations; and ● Do not italicize the signals or the “and.” For example: For further discussion of this issue, see, for example, State v. Gounagias, 153 P. 9, 15 (Wash. 1915), which describes provocation; State v. Stonehouse, 555 P. 772, 779 (Wash. 1907), which lists excuses; and WENDY BROWN & JOHN BLACK, STATES OF INJURY: POWER AND FREEDOM 34 (1995), which examines harm. -

Oh No! a New Bluebook!

Michigan Law Review Volume 90 Issue 6 1992 Oh No! A New Bluebook! James D. Gordon III Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation James D. Gordon III, Oh No! A New Bluebook!, 90 MICH. L. REV. 1698 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol90/iss6/39 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OH NO! A NEW BLUEBOOK! James D. Gordon Ill* THE BLUEBOOK: A UNIFORM SYSTEM OF CITATION. 15th ed. By the Columbia Law Review, the Harvard Law Review, the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, and The Yale Law Journal Cambridge: Harvard Law Review Association. 1991. Pp. xvii, 343. Paper, $8.45. The fifteenth edition of A Uniform System of Citation is out, caus ing lawyers and law students everywhere to hyperventilate with excite ment. Calm down. The new edition is not likely to overload the pleasure sensors in the brain. The title, A Uniform System ofCitation, has always been somewhat odd. The system is hardly uniform, and the book governs style as well as citations. 1 Moreover, nobody calls it by its title; everybody calls it The Bluebook. In fact, the book's almost nameless2 editors have amended the title to reflect this fact: it is now titled The Bluebook.· A Uniform System of Citation. -

Author Citations and the Indexer

Centrepiece to The Indexer, September 2013 C1 Author citations and the indexer Sylvia Coates C4 Tips for newcomers: Wellington 2013 Compiled by Jane Douglas C7 Reflections on the Wilson judging for 2012 Margie Towery Author citations and the indexer Sylvia Coates Sylvia Coates explores the potentially fraught matter of how to handle author citations in the index, looking first at the extensive guidelines followed by US publishers, and then briefly considering British practice where it is rare for an indexer to be given any such guidelines. In both situations the vital thing is to be clear from the very beginning exactly what your client’s expectations are. As an indexing instructor for over 12 years, I have observed discussion of this individual in relationship to their actions that most students assume that indexing names is an easy or to an event and not as a reference as is the case with a task. Unfortunately, as experienced indexers come to under- citation. stand, this is not the case and there are a myriad of issues Editors rightly expect the subject of any text discussion to to navigate when indexing names. An examination of all be included in the index. More problematic are the names of these issues is beyond the scope of this article, and my ‘mentioned in passing.’ Some clients expect to see every discussion will be limited to the indexing of name and author single name included in the text, regardless of whether the citations for US and British publishers. name is a passing mention or not. Other clients thankfully I will define what is and is not an author citation, and allow the indexer to use their own judgement in following briefly review the two major citation systems and style the customary indexing convention on what constitutes a guides pertinent to author citations. -

Washington Apple Pi Journal, May 1988

Wa1hington Journal of WasGhington Appl e Pi, Ltd Volume. 10 may 1988 number 5 Hiahliaht.1 ' . ~ The Great Apple Lawsuit- (pgs4&so) • Timeout AppleWorks Enhancements - I IGs •Personal Newsletter & Publish It! ~ MacNovice: Word Processing- The Next Generati on ~ Views & Reviews: MidiPaint and Performer ~ Macintosh Virus: Technical Notes In This Issue. Officers & Staff, Editorial ................................ ...................... 3 Personal Newsletter and Publish It! .................... Ray Settle 40* President's Corner ........................................... Tom Warrick 4 • GameSIG News ....................................... Charles Don Hall 41 Event Queue, General Information, Classifieds ..................... 6 Plan for Use of Tutorial Tapes & Disks ................................ 41 AV-SIG News .............................................. Nancy Sefcrian 6 The Design Page for W.A.P .................................. Jay Rohr 42 Commercial Classifieds, Job Mart .......................................... 7 MacNovice Column: Word Processing .... Ralph J. Begleiter 47 * WAP Calendar, SIG News ..................................................... 8 Developer's View: The Great Apple Lawsuit.. ..... Bill Hole 50• WAP Hotline............................................................. ............. 9 Macintosh Bits & Bytes ............................... Lynn R. Trusal 52 Q & A ............................... Robert C. Platt & Bruce F. Field 10 Macinations 3 .................................................. Robb Wolov 56 Using -

1 the YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 128 STYLE SHEET the Yale Law Journal Follows the Bluebook: a Uniform System of Citation (20Th

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 128 STYLE SHEET The Yale Law Journal follows The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (20th ed. 2015) for citation form and the Chicago Manual of Style (17th ed. 2017) for stylistic matters not addressed by The Bluebook. For the rare situations in which neither of these works covers a particular stylistic matter, we refer to the Government Printing Office (GPO) Style Manual (31st ed. 2016). The Journal’s official reference dictionary is Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. This Style Sheet codifies Journal-specific guidelines that take precedence over these sources. Rules 1-21 correspond to and supplement Rules 1-21 in the Bluebook. Rule 22 focuses on recurring matters of style that are not addressed in the Bluebook. Throughout, several rules have red titles; this indicates a correction to an error in the Bluebook, and these will be removed as the Bluebook is updated. Rule 1: Structure and Use of Citations.......................................................................................................... 3 S.R. 1.1(b): String Citations in Textual Sentences in Footnotes ............................................................... 3 S.R. 1.1: Two Claims in One Sentence ..................................................................................................... 3 S.R. 1.4: Order of Authorities ................................................................................................................... 4 S.R. 1.5(a)(i): Parenthetical Information.................................................................................................. -

APA Format Requirements Bluebook Vs

Developing Legal Citations in APA Format‐Identifying Differences Between Bluebook and APA Style Abbi Loving, Business Administration ‐ FRL Kellogg Honors College Convocation 2013 Mentor: Dr. John B. Wyatt III Introduction I set out on the journey of writing a legal citation guide with two key purposes in mind. The first of which was to give myself a competitive edge in law school and the second was to provide a clear explanation of how to construct legal citations in APA format. Legal writing is the foundation of first year law school, and as a student who will be attending law school in the fall; this capstone was a preparation tool in learning how to write legal citations. After speaking with numerous attorneys, it was brought to my attention that a common problem with law school students and graduates is they do not have a clear understanding of how to construct proper legal citations. In addition, the legal education system has a limited amount of resources that explain the legal citation process. Resources I came across were confusing and lacking clear explanations of the APA legal citation formatting process, which is essential to understand when writing articles for legal journals and law review. The problem is that law schools refer to the Bluebook for legal citations, but when citing references for law journals, APA format must be used. APA format incorporates various changes in the Bluebook style. I set out on a quest to solve this problem and created a guide that students, in addition to myself, will be able to refer to. -

Download, Including1 17N REU, Ramlink Partition, Jimymon-64 (ML Monitor)

C 0 T E T S ISSUE Published June 1996 COMMODORE WORLD 6 Wheels-Laying More Than A Patch THE NEWS MAGAZINE FOR COMMODORE 64 » 1'■ I 1J',[ K1. Bruce Thonuu 14 GOFA-A Modulap- Pcogpamming System Fob The Coeimodore 64 http://wviw.cmiweb.am/cwhtme.hlml George Flanagan General Manager Chinks ft Christiansen ♦ Editor Review; Doug Cot Ion ♦ 24 Software: Centipede 126 E>r Gaelwe R. Gasson Advegtisinq Sales A Look ai ihe Newesi Commodore I2S BBS Program Charles A. Christiansen (413) 525-0023 ♦ Graphic Acts Doug Cotton .UMN! '♦ 26 Jusr Fob Starters by Jason Compton Electronic Pre-Press & Pointing Maiuir/Holden Helpful Hints for Handling Disk Drives ♦ 30 Graphic Interpretation by Bruce Thomas Cover Design by Doug Cotton GEOS: For ti Good lime... 32 Carrier Detect by Gaelyne B. Gasson Tclecommunicationi News & Updates 36 S16 Beat by Mark Fellows Things to Look Out For When Program/Hint- the 65X16 Commodore1" and [he respective Commodore producl names are trademarks or registered trademarks of Commodore, a 38 Over The Edge by Jeffrey L. Jones division of Tulip Compulers. Commodore World is in no way aftiliated wilrtthe owner n! ".he Commodore logo ana technology. Commodore Programming in a SuperCPU World Commodore Worla (ISSN 1078-2515) is published 8 limos annually by Creative Micro Designs. Inc.. 15 Benton Drive, Easl Longrneadow MA 01028-0646. Secono-Class Postage Paid at EasL Longmeaflow MA. (USPS «)n-801| Annual subscnpiion rale is USS29.95 fci U.S. addresses. USS35.95(orC3nada0'Maiico.USSJS.95!orallECCounlnB5. Department paymanlsmusl be provided in U S. Dollars. Mail subscriptions 2 From the Editor to CW Subscriptions, do Crestiva Micro Designs. -

Disengaging from the Bluebook

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Caveat Volume 46 Issue 1 2012 Old Habits Die Hard: Disengaging from the Bluebook Mark Garibyan University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr_caveat Part of the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Mark Garibyan, Comment, Old Habits Die Hard: Disengaging from the Bluebook, 46 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM CAVEAT 71 (2012). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr_caveat/vol46/iss1/15 This Comment was originally cited as Volume 2 of the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Online. Volumes 1, 2, and 3 of MJLR Online have been renumbered 45, 46, and 47 respectively. These updated Volume numbers correspond to their companion print Volumes. Additionally, the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Online was renamed Caveat in 2015. This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Caveat by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN J OURNAL of LAW REFORM ONLINE COMMENT OLD HABITS DIE HARD: DISENGAGING FROM THE BLUEBOOK Mark Garibyan* Incoming first-year law students dread many aspects of what lies ahead: the cold calls, the challenging course load, and the general stress -

The University of Chicago Manual of Legal Citation ("The Maroon Book"), 21 J

UIC Law Review Volume 21 Issue 1 Article 12 Fall 1987 The University of Chicago Manual of Legal Citation ("The Maroon Book"), 21 J. Marshall L. Rev. 233 (1987) Joel R. Cornwell Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Legal Profession Commons, and the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Joel R. Cornwell, The University of Chicago Manual of Legal Citation ("The Maroon Book"), 21 J. Marshall L. Rev. 233 (1987) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol21/iss1/12 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEW THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MANUAL OF LEGAL CITATION ("THE MAROON BOOK"), UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, 1986, 25 PAGES, PAPERBACK: $3.50 Reviewed by Joel R. Cornwell* When human endeavors become dysfunctional on account of form, the form must be reworked to serve the end of function. One can point to many revolutions in human thought which have been compelled by this end, among them the rise of analytical philosophy and legal realism in the early twentieth century.' One can also make too much over a citation manual. Nevertheless, the emergence of the University of Chicago Manual of Legal Citation marks a functional revolution in an admittedly narrow field and, at a minimum, sends an overdue message to the Harvard Law Review Association, which has heretofore monopolized legal citation form with its manual, A Uniform System of Citation, a.k.a. -

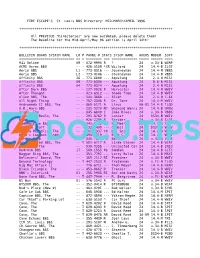

S 314 Area Code BBS Directory

FIRE ESCAPE'S St. Louis BBS Directory: MID-MARCH/APRIL 1996 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ All PREVIOUS "Directories" are now outdated, please delete them! The Deadline for the Mid-April/May 96 edition is April 14th! ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ BULLETIN BOARD SYSTEM NAME L# P PHONE # STATS SYSOP NAME HOURS MODEM SOFT ============================ == = ======== === ============= ===== ====== ==== 911 Online 09 - 872-9990 R ? 24 v.34-B WGRP ACME Acres BBS -- - 426-5159 *CR Wizlord 24 14.4-B SLGT Aerie BBS L1 - 773-8316 --- Journeyman 24 14.4-N VBBS Aerie BBS L2 - 773-8186 --- Journeyman 24 14.4-B VBBS Affinity BBS 26 - 771-6800 --- Aqualung 24 2.4-N MISC Affinity BBS 09 - 771-6300 --- Aqualung 24 9.6-B MISC Affinity BBS 04 - 771-9374 --- Aqualung 24 2.4-N MISC After Dark BBS -- - 227-9828 R Harvester 24 14.4-N WWIV After Thought -- - 423-6312 --- Shade Tree 24 14.4-B WWIV Alien BBS, The -- - 544-3668 --- Alien 24 2.4-N C-64 All Night Thing -- - 752-3308 R Dr. Tone 24 14.4-M WWIV Andromeda II BBS, The -- - 869-5171 A Linus 06-01 14.4-B TLGD A.R. Ware BBS -- - 231-9270 N? Weekend Warri 24 14.4-B UNKW Arena, The -- - 845-6849 C Jake Blues 24 v.34-B VBBS Asgardian Realm, The -- - 291-6762 R Lancer 24 DS34-B WWIV Babylon 7 -- - 926-2206 R Strider 24 v.34-B SLGT BadMedicine BBS -- T 341-5038 AR BadMedic 22-07 14.4-B TRI Balls & Shaft -- - 532-4409 --- Gambit 24 DS34-B WWIV Banana Republic, The -- - 282-3337 CR Dr.