ON 23(2) 303-306.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Auto Guia Version Ingles

Parque Natural Metropolitano Tel: (507) 232-5516/5552 Fax: (507) 232-5615 www.parquemetropolitano.org Ave. Juan Pablo II final P.O. Box 0843-03129 Balboa, Ancón, Panamá República de Panamá 2 Taylor, L. 2006. Raintree Nutrition, Tropical Plant Database. http://www.rain- Welcome to the Metropolitan Natural Park, the lungs of Panama tree.com/plist.htm. Date accessed; February 2007 City! The park was established in 1985 and contains 232 hectares. It is one of the few protected areas located within the city border. Thomson, L., & Evans, B. 2006. Terminalia catappa (tropical almond), Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Permanent Agriculture Resources You are about to enter an ecosystem that is nearly extinct in Latin (PAR), Elevitch, C.R. (ed.). http://www.traditionaltreeorg . Date accessed March America: the Pacific dry forests. Whether your goals for this walk 2007-04-23 are a simple walk to keep you in shape or a careful look at the forest and its inhabitants, this guide will give you information about Young, A., Myers, P., Byrne, A. 1999, 2001, 2004. Bradypus variegatus, what can be commonly seen. We want to draw your attention Megalonychidae, Atta sexdens, Animal Diversity Web. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Bradypus_var toward little things that may at first glance seem hidden away. Our iegatus.html. Date accessed March 2007 hope is that it will raise your curiosity and that you’ll want to learn more about the mysteries that lie within the tropical forest. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The contents of this book include tree identifications, introductions Text and design: Elisabeth Naud and Rudi Markgraf, McGill University, to basic ecological concepts and special facts about animals you Montreal, Canada. -

Threatened Birds of the Americas

GREAT XENOPS Megaxenops parnaguae K12 Dry woodland in the heavily populated interior of north-east Brazil is the habitat of this apparently very local and little known mid-storey bark-gleaner, which is presumably suffering from land clearance. DISTRIBUTION The Great Xenops (see Remarks 1) is known from a few localities thinly scattered over a large area in interior north-eastern and central Brazil. The assumption that it occurs in “probably all the caatinga region of northeastern Brazil” (Vaurie 1980: 325 and map 55) is in need of further supporting evidence, but it is certainly true that very recent records have hugely extended its known range. Ceará A specimen was collected in March 1925 at Várzea Formosa, near Ipueiras, on the eastern escarpments of the Serra da Ibiapaba (Hellmayr 1929a). Sight records of this bird are known from Chapada do Araripe, recently (Vaurie 1980, Teixeira et al. 1989, J. F. Pacheco and B. M. Whitney in litt. 1991, M. Pearman in litt. 1992), Quixadá in 1982 and Tauá in 1983 (R. Otoch in litt. 1986). Piauí The type-material was two specimens collected in June 1903 on the trail from Parnaguá to Olho d'Agua (untraceable); several other specimens were shot (but not conserved) at the same place on the same day (Reiser 1926). There is a sight record from near Manoel Emídio in July 1987 (P. Roth in litt. 1987; also Roth 1987c, 1989b). The species is well represented in Serra da Capivara National Park (Olmos in press). Six specimens (in AMNH, CM) were taken over two days at Parnaguá, 300 m, in June 1927 (see Remarks 2). -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Evolution of the Ovenbird-Woodcreeper Assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Б/ Major Shifts in Nest Architecture and Adaptive Radiatio

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 37: 260Á/272, 2006 Evolution of the ovenbird-woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) / major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation Á Martin Irestedt, Jon Fjeldsa˚ and Per G. P. Ericson Irestedt, M., Fjeldsa˚, J. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2006. Evolution of the ovenbird- woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Á/ major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation. Á/ J. Avian Biol. 37: 260Á/272 The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) form an extraordinary morphologically and ecologically diverse passerine radiation, which includes many examples of species that are superficially similar to other passerine birds as a resulting from their adaptations to similar lifestyles. The ovenbirds further exhibits a truly remarkable variation in nest types, arguably approaching that found in the entire passerine clade. Herein we present a genus-level phylogeny of ovenbirds based on both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA including a more complete taxon sampling than in previous molecular studies of the group. The phylogenetic results are in good agreement with earlier molecular studies of ovenbirds, and supports the suggestion that Geositta and Sclerurus form the sister clade to both core-ovenbirds and woodcreepers. Within the core-ovenbirds several relationships that are incongruent with traditional classifications are suggested. Among other things, the philydorine ovenbirds are found to be non-monophyletic. The mapping of principal nesting strategies onto the molecular phylogeny suggests cavity nesting to be plesiomorphic within the ovenbirdÁ/woodcreeper radiation. It is also suggested that the shift from cavity nesting to building vegetative nests is likely to have happened at least three times during the evolution of the group. -

Check List 5(2): 222–237, 2009

Check List 5(2): 222–237, 2009. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Birds (Aves), Serrania Sadiri, Parque Nacional Madidi, Depto. La Paz, Bolivia Peter Andrew Hosner 1 Kenneth David Behrens 2 A. Bennett Hennessey 3 1 University of Kansas, Museum of Natural History, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Division of Ornithology. Dyche Hall, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66046. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Tropical Birding, 1 Toucan Way. Bloubergrise 7441, South Africa. 3 Asociación Civil Armonía. Avenida Lomas de Arena, Casilla 3566, Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Abstract We surveyed the Serrania Sadiri for birds at elevations between 500-950m for a combined total of 15 days in three different months. The area surveyed was along the Tumupasa/San Jose de Uchupiamones trail at the edge of Parque Nacional Madidi in Depto. La Paz, Bolivia. We report observations of 231 species of birds detected by sight and sound, including many outlying ridge specialists. We report and present photographs of a new species for Depto. La Paz (Caprimulgis nigrescens), the second Bolivian localities for Porphyrolaema prophyrolaema, Zimerius cinereicapillus, and Basileuterus chrysogaster, and five new species records for Parque Nacional Madidi. Introduction Foothills and outlying ridges of the Andes are From the small village of Tumupasa (14°8'46" S, often very difficult or impossible to access. As a 67°53'17" W; 400 m a.s.l; Figures 1 and 2), an old result, many of the specialist bird species in these trail leads generally southwest over the Serrania areas are poorly known and some only recently Sadiri to the town of San Jose de Uchupiamones described, and these areas generally have unique (14°12'47" S, 68°03'14" W; 520 m a.s.l). -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae)

The Auk 116(4):891-911, 1999 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF NEOTROPICAL OVENBIRDS (FURNARIIDAE) KRZYSZTOF ZYSKOWSKI • AND RICHARD O. PRUM NaturalHistory Museum and Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Wereviewed the tremendousarchitectural diversity of ovenbird(Furnari- idae) nestsbased on literature,museum collections, and new field observations.With few exceptions,furnariids exhibited low intraspecificvariation for the nestcharacters hypothe- sized,with the majorityof variationbeing hierarchicallydistributed among taxa. We hy- pothesizednest homologies for 168species in 41 genera(ca. 70% of all speciesand genera) and codedthem as 24 derivedcharacters. Forty-eight most-parsimonious trees (41 steps,CI = 0.98, RC = 0.97) resultedfrom a parsimonyanalysis of the equallyweighted characters using PAUP,with the Dendrocolaptidaeand Formicarioideaas successiveoutgroups. The strict-consensustopology based on thesetrees contained 15 cladesrepresenting both tra- ditionaltaxa and novelphylogenetic groupings. Comparisons with the outgroupsdemon- stratethat cavitynesting is plesiomorphicto the furnariids.In the two lineageswhere the primitivecavity nest has been lost, novel nest structures have evolved to enclosethe nest contents:the clayoven of Furnariusand the domedvegetative nest of the synallaxineclade. Althoughour phylogenetichypothesis should be consideredas a heuristicprediction to be testedsubsequently by additionalcharacter evidence, this first cladisticanalysis -

On the Origin and Evolution of Nest Building by Passerine Birds’

T H E C 0 N D 0 R r : : ,‘ “; i‘ . .. \ :i A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY ,I : Volume 99 Number 2 ’ I _ pg$$ij ,- The Condor 99~253-270 D The Cooper Ornithological Society 1997 ON THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF NEST BUILDING BY PASSERINE BIRDS’ NICHOLAS E. COLLIAS Departmentof Biology, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1606 Abstract. The object of this review is to relate nest-buildingbehavior to the origin and early evolution of passerinebirds (Order Passeriformes).I present evidence for the hypoth- esis that the combinationof small body size and the ability to place a constructednest where the bird chooses,helped make possiblea vast amountof adaptiveradiation. A great diversity of potential habitats especially accessibleto small birds was created in the late Tertiary by global climatic changes and by the continuing great evolutionary expansion of flowering plants and insects.Cavity or hole nests(in ground or tree), open-cupnests (outside of holes), and domed nests (with a constructedroof) were all present very early in evolution of the Passeriformes,as indicated by the presenceof all three of these basic nest types among the most primitive families of living passerinebirds. Secondary specializationsof these basic nest types are illustratedin the largest and most successfulfamilies of suboscinebirds. Nest site and nest form and structureoften help characterizethe genus, as is exemplified in the suboscinesby the ovenbirds(Furnariidae), a large family that builds among the most diverse nests of any family of birds. The domed nest is much more common among passerinesthan in non-passerines,and it is especially frequent among the very smallestpasserine birds the world over. -

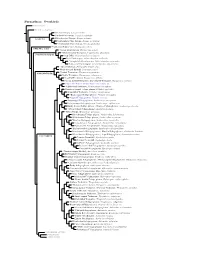

Furnariinae Species Tree, Part 1

Furnariinae: Ovenbirds Sclerurinae Dendrocolaptinae Streaked Xenops, Xenops rutilans Slender-billed Xenops, Xenops tenuirostris Xenops minutus XENOPINI White-throated Xenops, Northwestern Plain Xenops, Xenops mexicanus !Southeastern Plain Xenops, Xenops genibarbus !Point-tailed Palmcreeper, Berlepschia rikeri BERLEPSCHIINI ! Rufous-tailed Xenops, Microxenops milleri !White-throated Treerunner, Pygarrhichas albogularis PYGARRHICHADINI Crag Chilia, Ochetorhynchus melanurus Rock Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus andaecola !Straight-billed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus ruficaudus Band-tailed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus phoenicurus !Spotted Barbtail, Premnoplex brunnescens White-throated Barbtail, Premnoplex tatei !Pearled Treerunner, Margarornis squamiger MARGARORNINI Ruddy Treerunner, Margarornis rubiginosus Beautiful Treerunner, Margarornis bellulus Fulvous-dotted Treerunner / Star-chested Treerunner, Margarornis stellatus Cryptic Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti !Pale-browed Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes leucophrus Cinnamon-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor pyrrhodes Sharp-billed Treehunter, Philydor contaminatus !Black-capped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor atricapillus Alagoas Foliage-gleaner, Philydor novaesi Slaty-winged Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscipennis Rufous-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops erythrocercus Dusky-cheeked Foliage-gleaner / Bamboo Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops dorsalis !White-collared Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscus !Great Xenops, Megaxenops parnaguae Ochre-breasted Foliage-gleaner, Anabacerthia lichtensteini White-browed -

Minimum Longevity Estimates for Some Neotropical Landbirds of Southeastern Peru

Minimum longevity estimates for some Neotropical landbirds of southeastern Peru Authors: Micah N. Scholer, Christopher L. Merkord, Gustavo A. Londoño, and Jill E. Jankowski Source: The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 130(3) : 818-823 Published By: Wilson Ornithological Society URL: https://doi.org/10.1676/17-095.1 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/The-Wilson-Journal-of-Ornithology on 1/10/2019 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by University of Florida 818 The Wilson Journal of Ornithology Vol. 130, No. 3, September 2018 Selection and justification for a suite of indicator of Cuban vertebrates]. La Habana (Cuba): Editorial species. Ecological Indicators. 44:148–163. Academia; p. 214. Pavez EF, Lobos GA, Jaksic FM. 2010. Cambios de largo Snyder NFR, Beissinger SR, Chandler RE. 1989. Repro- plazo en el paisaje y los ensambles de micromam´ıferos duction and demography of the Florida Everglades y rapaces en Chile central [Long-term changes in (Snail) Kite. -

Ecology and Flock-Following Behavior of the Wedge-Billed Woodcreeper in Eastern Ecuador Abigail Darrah University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 Ecology and Flock-Following Behavior of the Wedge-Billed Woodcreeper in Eastern Ecuador Abigail Darrah University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, Poultry or Avian Science Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Darrah, Abigail, "Ecology and Flock-Following Behavior of the Wedge-Billed Woodcreeper in Eastern Ecuador" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 807. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/807 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ECOLOGY AND FLOCK-FOLLOWING BEHAVIOR OF THE WEDGE-BILLED WOODCREEPER IN EASTERN ECUADOR ECOLOGY AND FLOCK-FOLLOWING BEHAVIOR OF THE WEDGE-BILLED WOODCREEPER IN EASTERN ECUADOR A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology by Abigail Darrah Ohio University Bachelor of Science in Biology, 2003 University of Arkansas Master of Science in Biology, 2006 May 2013 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT The wedge-billed woodcreeper (Glyphorynchus spirurus) is a common understory suboscine passerine of lowland Neotropical rainforests. It frequently joins mixed-species understory flocks but also regularly forages alone, and thus is an excellent model species on which to conduct comparative behavioral observations to examine the hypothesized costs and benefits of flock- following. Individuals exhibit variable flocking propensities (proportion of time spent with flocks), and thus observing the correlations between flocking propensity and physical and environmental factors can provide further insight into the importance of flock-following to the ecology of this species.