Botanical Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Pruritus: a Systematic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rare Diseases: GI/Metabolic

Rare Diseases: GI / Metabolic Ciara Kennedy, PhD, MBA – Head of Cholestatic Liver Disease David Piccoli, MD – Chief of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition, Children’s Hospital Of Philadelphia Our purpose We enable people with life-altering conditions to lead better lives. The “SAFE HARBOR” Statement Under the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 Statements included in this announcement that are not historical facts are forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements can be identified by words such as “aspiration”, “will”, “expect”, “forecast”, “aspiration”, “potential”, “estimates”, “may”, “anticipate”, “target”, “project” or similar expressions suitable for identifying information that refers to future events. Forward-looking statements involve a number of risks and uncertainties and are subject to change at any time. In the event such risks or uncertainties materialize, Shire’s results could be materially adversely affected. The risks and uncertainties include, but are not limited to, that: . Shire’s products may not be a commercial success; . revenues from ADDERALL XR are subject to generic erosion and revenues from INTUNIV will become subject to generic competition starting in December 2014; . the failure to obtain and maintain reimbursement, or an adequate level of reimbursement, by third-party payors in a timely manner for Shire's products may impact future revenues, financial condition and results of operations; . Shire conducts its own manufacturing operations for certain of its products and is reliant on third party contractors to manufacture other products and to provide goods and services. Some of Shire’s products or ingredients are only available from a single approved source for manufacture. Any disruption to the supply chain for any of Shire’s products may result in Shire being unable to continue marketing or developing a product or may result in Shire being unable to do so on a commercially viable basis for some period of time. -

European Guideline Chronic Pruritus Final Version

EDF-Guidelines for Chronic Pruritus In cooperation with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) and the Union Européenne des Médecins Spécialistes (UEMS) E Weisshaar1, JC Szepietowski2, U Darsow3, L Misery4, J Wallengren5, T Mettang6, U Gieler7, T Lotti8, J Lambert9, P Maisel10, M Streit11, M Greaves12, A Carmichael13, E Tschachler14, J Ring3, S Ständer15 University Hospital Heidelberg, Clinical Social Medicine, Environmental and Occupational Dermatology, Germany1, Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland2, Department of Dermatology and Allergy Biederstein, Technical University Munich, Germany3, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Brest, France4, Department of Dermatology, Lund University, Sweden5, German Clinic for Diagnostics, Nephrology, Wiesbaden, Germany6, Department of Psychosomatic Dermatology, Clinic for Psychosomatic Medicine, University of Giessen, Germany7, Department of Dermatology, University of Florence, Italy8, Department of Dermatology, University of Antwerpen, Belgium9, Department of General Medicine, University Hospital Muenster, Germany10, Department of Dermatology, Kantonsspital Aarau, Switzerland11, Department of Dermatology, St. Thomas Hospital Lambeth, London, UK12, Department of Dermatology, James Cook University Hospital Middlesbrough, UK13, Department of Dermatology, Medical University Vienna, Austria14, Department of Dermatology, Competence Center for Pruritus, University Hospital Muenster, Germany15 Corresponding author: Elke Weisshaar -

Update of the Guideline on Chronic Pruritus

Update of the Guideline on Chronic Pruritus Developed by the Guideline Subcommittee “Chronic Pruritus” of the European Dermatology Forum Subcommittee Members: Prof. Dr. Elke Weisshaar, Heidelberg (Germany) Prof. Dr. Sonja Ständer, Münster (Germany) Prof. Dr. Erwin Tschachler, Wien (Austria) Prof. Dr. Torello Lotti, Florence (Italy) Prof. Dr. Johannes Ring, Munich (Germany) Prof. Dr. Laurent Misery, Brest (France) Dr. Markus Streit, Aarau (Switzerland) Prof. Dr. Thomas Mettang, Wiesbaden (Germany) Prof. Dr. Jacek Szepietowski, Wroclaw (Poland) Prof. Dr. Joanna Wallengren, Lund (Sweden) Dr. Peter Maisel, Münster (Germany) Prof. Dr. Uwe Gieler, Gießen (Germany) Prof. Dr. Malcolm Greaves (Singapore) Prof. Dr. Ulf Darsow, Munich (Germany) Prof. Dr. Julien Lambert, Antwerp (Belgium) Members of EDF Guideline Committee: Prof. Dr. Werner Aberer, Graz (Austria) Prof. Dr. Dieter Metze, Münster (Germany) Prof. Dr. Martine Bagot, Paris (France) Dr. Kai Munte, Rotterdam (Netherlands) Prof. Dr. Nicole Basset-Seguin, Paris (France) Prof. Dr. Gilian Murphy, Dublin (Ireland) Prof. Dr. Ulrike Blume-Peytavi, Berlin (Germany) Prof. Dr. Martino Neumann, Rotterdam (Netherlands) Prof. Dr. Lasse Braathen, Bern (Switzerland) Prof. Dr. Tony Ormerod, Aberdeen (UK) Prof. Dr. Sergio Chimenti, Rome (Italy) Prof. Dr. Mauro Picardo, Rome (Italy) Prof. Dr. Alexander Enk, Heidelberg (Germany) Prof. Dr. Johannes Ring, Munich (Germany) Prof. Dr. Claudio Feliciani, Rome (Italy) Prof. Dr. Annamari Ranki, Helsinki (Finland) Prof. Dr. Claus Garbe, Tübingen (Germany) Prof. Dr. Berthold Rzany, Berlin (Germany) Prof. Dr. Harald Gollnick, Magdeburg (Germany) Prof. Dr. Rudolf Stadler, Minden (Germany) Prof. Dr. Gerd Gross, Rostock (Germany) Prof. Dr. Sonja Ständer, Münster (Germany) Prof. Dr. Vladimir Hegyi, Bratislava (Slovakia) Prof. Dr. Eggert Stockfleth, Berlin (Germany) Prof. Dr. -

Pruritus Ani (Itchy Bottom)

PRURITUS ANI (ITCHY BOTTOM) What is pruritus ani? Pruritus ani means a chronic (persistent) itchy feeling around the anus. The main symptom is an urge to scratch your anus which is difficult to resist. The urge to scratch may occur at any time. However, it tends to be more common after you have been to the toilet to pass faeces, and at night (particularly just before falling asleep). The itch may be made worse by heat, wool, moisture, leaking, soiling, stress, and anxiety. About 1 in 20 people develop pruritus ani at some stage. It is common in both adults and children. What causes pruritus ani? Pruritus ani is a symptom, not a final diagnosis. Various conditions may cause pruritus ani. However, in many cases the cause is not clear. This is called ‘idiopathic pruritus ani’, which means ‘itchy anus of unknown cause’. Known causes of pruritus ani There are various causes which include the following: Inflamed anal skin is a common cause (a localised dermatitis). The inflammation is usually due to the skin ‘reacting’ to small amounts of faeces (sometimes called stools or motions) left on the skin, and/or to sweat and moisture around the anus. Young children who may not wipe themselves properly, adults with sweaty jobs, and adults with a lot of hair round the anus may be especially prone to this. Thrush and fungal infections. These germs like it best in moist, warm, airless areas, such as around the anus. Thrush is more common in people with diabetes. Other infections such as scabies, herpes, anal warts and some other sexually transmitted diseases can cause itch around the anus. -

European Guideline on Chronic Pruritus in Cooperation with the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV)

European Guideline on Chronic Pruritus In cooperation with the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Weisshaar, Elke; Szepietowski, Jacek C.; Darsow, Ulf; Misery, Laurent; Wallengren, Joanna; Mettang, Thomas; Gieler, Uwe; Lotti, Torello; Lambert, Julien; Maisel, Peter; Streit, Markus; Greaves, Malcolm W.; Carmichael, Andrew; Tschachler, Erwin; Ring, Johannes; Staenders, Sonja Published in: Acta Dermato-Venereologica DOI: 10.2340/00015555-1400 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Weisshaar, E., Szepietowski, J. C., Darsow, U., Misery, L., Wallengren, J., Mettang, T., Gieler, U., Lotti, T., Lambert, J., Maisel, P., Streit, M., Greaves, M. W., Carmichael, A., Tschachler, E., Ring, J., & Staenders, S. (2012). European Guideline on Chronic Pruritus In cooperation with the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). Acta Dermato-Venereologica, 92(5), 563- 581. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-1400 Total number of authors: 16 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ LUND UNIVERSITY Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Pharmacological Interventions for Pruritus in Adult Palliative Care Patients (Review)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Pharmacological interventions for pruritus in adult palliative care patients (Review) Siemens W, Xander C, Meerpohl JJ, Buroh S, Antes G, Schwarzer G, Becker G Siemens W, Xander C, Meerpohl JJ, Buroh S, Antes G, Schwarzer G, Becker G. Pharmacological interventions for pruritus in adult palliative care patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD008320. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008320.pub3. www.cochranelibrary.com Pharmacological interventions for pruritus in adult palliative care patients (Review) Copyright © 2016 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 4 BACKGROUND .................................... 6 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 9 METHODS ...................................... 9 RESULTS....................................... 15 Figure1. ..................................... 16 Figure2. ..................................... 22 Figure3. ..................................... 23 ADDITIONALSUMMARYOFFINDINGS . 34 DISCUSSION ..................................... 54 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 57 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 58 REFERENCES ..................................... 59 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 69 DATAANDANALYSES. 164 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Naltrexone versus placebo, Outcome 1 A) Pruritus on VAS scale (0-10 cm) in CP participants. ................................. -

Pruritus Ani Fact Sheet

PRURITUS ANI FACT SHEET What is Pruritus Ani? Pruritus Ani is an intense itching sensation at or near the anus. What causes Pruritus Ani? The most common cause of anal itching is excessive anal cleaning. Other less common causes include: Irritation: soaps, scented toilet tissue, feminine hygiene products, and creams or ointments can bring about the condition. Diet: foods containing caffeine may cause and/or contribute to Pruritus Ani. Coffee, tea, colas, and chocolate have caffeine. Other offenders may include tomatoes, ketchup, milk products and beer. Diarrhea: Pruritus Ani can be caused or aggravated by loose, runny stools. Anxiety: nervous tension and stress may cause or worsen anal itching. Other rare causes of Pruritus Ani include psoriasis, yeast infections, pinworms and contact dermatitis. How is Pruritus Ani treated? If you are experiencing an intense itching sensation in or near your anus, consult with your physician for proper diagnosis. He or she may recommend the following: • No soap – use only water when washing the anal area, keeping it as clean as possible. • Avoid the previously mentioned foods and beverages. • Avoid foods and beverages which may cause diarrhea. • Stop the use of medications and ointments on the anal area, except when prescribed by your physician. • Wear cotton undergarments. Pruritus Ani symptoms do not disappear immediately. Patience, following the above instructions and seeing your physician for a follow-up examination can eliminate your problems with anal itching. Fox Valley Surgical Associates 1818 N. Meade Street, Suite 240 West | Appleton, WI 54911 (920) 731-8131 or (800) 574-3872 www.fvsa-wi.com. -

Chapter 5 – Gastrointestinal System

CHAPTER 5 – GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Nurses in Primary Care. The content of this chapter was revised October 2011. Table of Contents ASSESSMENT OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM ......................................5–1 EXAMINATION OF THE ABDOMEN ........................................................................5–2 COMMON PROBLEMS OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM .........................5–4 Anal Fissure .......................................................................................................5–4 Constipation .......................................................................................................5–5 Dehydration (Hypovolemia) ...............................................................................5–8 Diarrhea ...........................................................................................................5–11 Diverticular Disease .........................................................................................5–15 Diverticulitis ......................................................................................................5–15 Diverticulosis ....................................................................................................5–16 Dyspepsia ........................................................................................................5–17 Gallbladder Disease .........................................................................................5–18 Biliary Colic ......................................................................................................5–21 -

Pruritus: a New Look at an Old Problem

problems in family practice Pruritus: A New Look a t an Old Problem Richard Rubenstein, MD Chicago, Illinois Pruritus, a frequent complaint heard by family physicians, is a complex physiolog ical phenomenon mediated by histamine and other peptides. It is associated with a number of common dermatologic diseases but has significant psychological fac tors as well. In some patients pruritus may be an important marker of systemic disease. Diagnostic approach includes a careful physical examination of primary skin lesions and goal-directed laboratory tests. Careful skin care and oral antihis tamines are basic measures to alleviate pruritus. ruritus, or itching, is a frequent complaint heard by PATHOPHYSIOLOGY P family physicians. Although generally considered to be a benign symptom, pruritis can have adverse affects on The actual sensation of itching is believed to be produced patients’ well-being and can be incapacitating in its severe by stimulation of the small, slow C and possibly A delta form. The mechanisms of pruritus are not particularly fibers in the superficial layers of the skin. These are non well understood and are compounded by the subjective myelinated, polymodal fibers, each having varying nature of the process itself. Pruritus occurs with a host of threshholds. None are uniquely adapted to itch; indeed, dermatologic conditions but can also be a marker of sys pain, touch, and pressure can be registered centrally by temic disease. It is clearly important for the family phy these fibers. sician to be aware of the varied causes of itching. Itching is distinct from pain but related; it is sometimes Everyone knows what the sensation of itch is, yet it is called mild pain. -

The Clinical Conundrum of Pruritus Victoria Garcia-Albea, Karen Limaye

FEATURE ARTICLE The Clinical Conundrum of Pruritus Victoria Garcia-Albea, Karen Limaye ABSTRACT: Pruritus is a common complaint for derma- Pruritus is also the most common symptom in derma- tology patients. Diagnosing the cause of pruritus can tological disease and can be a symptom of several sys- be difficult and is often frustrating for patients and pro- temic diseases (Bernhard, 1994). The overall incidence viders. Even after the diagnosis is made, it can be a chal- of pruritus is unknown because there are no epidemio- lenge to manage and relieve pruritus. This article reviews logical databases for pruritus (Norman, 2003). According common and uncommon causes of pruritus and makes to a 2003 study, pruritus and xerosis are the most com- recommendations for proper and thorough evaluation mon dermatological problems encountered in nursing and management. home patients (Norman, 2003). Key words: Itch, Pruritus INTRODUCTION ETIOLOGY Pruritus (itch) is the most frequent symptom in derma- The skin is equipped with a network of afferent sensory tology (Serling, Leslie, & Maurer, 2011). Itch is the pre- and efferent autonomic nerve branches that respond to dominant symptom associated with acute and chronic various chemical mediators found in the skin (Bernhard, cutaneous disease and is a major symptom in systemic dis- 1994). It is believed that maximal itch production is ease (Elmariah & Lerner, 2011; Steinhoff, Cevikbas, Ikoma, achieved at the basal layer of the epidermis, below which & Berger, 2011). It can be a frustration for both the patient pain is perceived (Bernhard, 1994). Autonomic nerves in- and the clinician. This article will attempt to provide an nervate hair follicles, pili erector muscles, blood vessels, overview of pruritus, a method for thorough and com- eccrine, apocrine, and sebaceous glands (Bernhard, 1994). -

Superbill ICD-10(2)

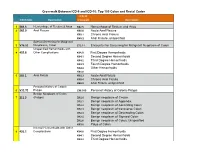

SUPERBILL Name Appt Date Time Ticket # Today's Charge Primary Insurance Acct. # Today's Payment Pt. Balance Co-pay Today's Balance Office Visits Procedure Diagnosis (Continued) New Patients 99201 Problem Focused 45300 Proctosigmoidoscopy R15.1 Fecal Smearing 99202 Expanded Problem 46600 Diagnostic Anoscopy K62.5 Hemorrhage Anus/Rectum 99203 Detailed 46221 Hemorrhoid Ligation K64.8 Internal Hemorrhoids (w/o mention of 99204 Moderate 46220 Removal, Anal Tag degree) 99205 Comprehensive 46230 Removal, 2+ Anal Tags K64.9 Internal Hemorrhoids - Bleeding (w/o 46083 Incision Ext. Hemorrhoid mention of degree) Consultations 46320 Excision Ext. Hemorrhoid K64.0 1st Degree Hemorrhoids (Grade I) - 99241 Problem Focused 45005 I&D Abscess w/o Proplapse Outside Anal Canal 99242 Expanded Problem 46910 Viral Wart, Condyloma, K64.1 2nd Degree Hemorrhoids (Grade II) – Papilloma destruction by That Prolapse with Straining but 99243 Detailed electrodesiccation (any Retract Spontaneously number) K64.2 3rd Degree Hemorrhoids (Grade III) – 99244 Moderate That Prolapse with Straining and 99245 Comprehensive 46924 Viral Wart, Condyloma, Require Manual Replacement Papilloma destruction by Established Patients laser, cryosurgery, K64.3 4th Degree Hemorrhoids (Grade IV) – 99211 Problem Focused electrosurgery (any number) with Prolapsed Tissue That Cannot be 99212 Expanded Problem J3490 Nitroglycerin Ointment Manually Replaced 99213 Detailed A4550 Surgical Trays O22.4 Hemorrhoids Complicating Pregnancy 99214 Moderate Diagnosis O87.2 Hemorrhoids Complicating Puerperium -

ICD-10 Coding

Crosswalk Between ICD-9 and ICD-10: Top 100 Colon and Rectal Codes ICD-10 ICD-9 Code Description Crosswalk Description 1 569.3 Hemorrhage of Rectum & Anus K62.5 Hemorrhage of Rectum and Anus 2 565.0 Anal Fissure K60.0 Acute Anal Fissure K60.1 Chronic Anal Fissure K60.2 Anal Fissure, unspecified Special Screening for Malignant 3 V76.51 Neoplasms, Colon Z12.11 Encounter for Screening for Malignant Neoplasm of Colon Unspecified Hemorrhoids with 4 455.8 Other Complications K64.0 First Degree Hemorrhoids K64.1 Second Degree Hemorrhoids K64.2 Third Degree Hemorrhoids K64.3 Fourth Degree Hemorrhoids K64.4 Other Hemorrhoids K64.8 5 565.1 Anal Fistula K60.3 Acute Anal Fistula K60.4 Chronic Anal Fistula K60.5 Anal Fistula, unspecified Personal History of Colonic 6 V12.72 Polyps Z86.010 Personal History of Colonic Polyps Benign Neoplasm of Colon 7 211.3 (Polyps) D12.0 Benign neoplasm of Cecum D12.1 Benign neoplasm of Appendix D12.2 Benign neoplasm of Ascending Colon D12.3 Benign neoplasm of transverse Colon D12.4 Benign neoplasm of Descending Colon D12.5 Benign neoplasm of Sigmoid Colon D12.6 Benign neoplasm of Colon, Unspecified K63.5 Polyp of Colon Internal Hemorrhoids with Other 8 455.2 Complications K64.0 First Degree Hemorrhoids K64.1 Second Degree Hemorrhoids K64.2 Third Degree Hemorrhoids Crosswalk Between ICD-9 and ICD-10: Top 100 Colon and Rectal Codes K64.3 Fourth Degree Hemorrhoids K64.8 Other Hemorrhoids 9 569.42 Anal or Rectal Pain K62.89 Other Specified Diseases of Anus and Rectum 10 698.0 Pruritus Ani L29.0 Pruritus Ani Internal Hemorrhoids