Global Financial Markets Liquidity Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Up to EUR 3,500,000.00 7% Fixed Rate Bonds Due 6 April 2026 ISIN

Up to EUR 3,500,000.00 7% Fixed Rate Bonds due 6 April 2026 ISIN IT0005440976 Terms and Conditions Executed by EPizza S.p.A. 4126-6190-7500.7 This Terms and Conditions are dated 6 April 2021. EPizza S.p.A., a company limited by shares incorporated in Italy as a società per azioni, whose registered office is at Piazza Castello n. 19, 20123 Milan, Italy, enrolled with the companies’ register of Milan-Monza-Brianza- Lodi under No. and fiscal code No. 08950850969, VAT No. 08950850969 (the “Issuer”). *** The issue of up to EUR 3,500,000.00 (three million and five hundred thousand /00) 7% (seven per cent.) fixed rate bonds due 6 April 2026 (the “Bonds”) was authorised by the Board of Directors of the Issuer, by exercising the powers conferred to it by the Articles (as defined below), through a resolution passed on 26 March 2021. The Bonds shall be issued and held subject to and with the benefit of the provisions of this Terms and Conditions. All such provisions shall be binding on the Issuer, the Bondholders (and their successors in title) and all Persons claiming through or under them and shall endure for the benefit of the Bondholders (and their successors in title). The Bondholders (and their successors in title) are deemed to have notice of all the provisions of this Terms and Conditions and the Articles. Copies of each of the Articles and this Terms and Conditions are available for inspection during normal business hours at the registered office for the time being of the Issuer being, as at the date of this Terms and Conditions, at Piazza Castello n. -

(NSE), India, Using Box Spread Arbitrage Strategy

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business - September-December, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2013 Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business Vol. 15, No. 3 (September - December 2013): 269 - 285 Efficiency of S&P CNX Nifty Index Option of the National Stock Exchange (NSE), India, using Box Spread Arbitrage Strategy G. P. Girish,a and Nikhil Rastogib a IBS Hyderabad, ICFAI Foundation For Higher Education (IFHE) University, Andhra Pradesh, India b Institute of Management Technology (IMT) Hyderabad, India Abstract: Box spread is a trading strategy in which one simultaneously buys and sells options having the same underlying asset and time to expiration, but different exercise prices. This study examined the effi- ciency of European style S&P CNX Nifty Index options of National Stock Exchange, (NSE) India by making use of high-frequency data on put and call options written on Nifty (Time-stamped transactions data) for the time period between 1st January 2002 and 31st December 2005 using box-spread arbitrage strategy. The advantages of box-spreads include reduced joint hypothesis problem since there is no consideration of pricing model or market equilibrium, no consideration of inter-market non-synchronicity since trading box spreads involve only one market, computational simplicity with less chances of mis- specification error, estimation error and the fact that buying and selling box spreads more or less repli- cates risk-free lending and borrowing. One thousand three hundreds and fifty eight exercisable box- spreads were found for the time period considered of which 78 Box spreads were found to be profit- able after incorporating transaction costs (32 profitable box spreads were identified for the year 2002, 19 in 2003, 14 in 2004 and 13 in 2005) The results of our study suggest that internal option market efficiency has improved over the years for S&P CNX Nifty Index options of NSE India. -

Master Thesis the Use of Interest Rate Derivatives and Firm Market Value an Empirical Study on European and Russian Non-Financial Firms

Master Thesis The use of Interest Rate Derivatives and Firm Market Value An empirical study on European and Russian non-financial firms Tilburg, October 5, 2014 Mark van Dijck, 937367 Tilburg University, Finance department Supervisor: Drs. J.H. Gieskens AC CCM QT Master Thesis The use of Interest Rate Derivatives and Firm Market Value An empirical study on European and Russian non-financial firms Tilburg, October 5, 2014 Mark van Dijck, 937367 Supervisor: Drs. J.H. Gieskens AC CCM QT 2 Preface In the winter of 2010 I found myself in the heart of a company where the credit crisis took place at that moment. During a treasury internship for Heijmans NV in Rosmalen, I experienced why it is sometimes unescapable to use interest rate derivatives. Due to difficult financial times, banks strengthen their requirements and the treasury department had to use different mechanism including derivatives to restructure their loans to the appropriate level. It was a fascinating time. One year later I wrote a bachelor thesis about risk management within energy trading for consultancy firm Tensor. Interested in treasury and risk management I have always wanted to finish my finance study period in this field. During the master thesis period I started to work as junior commodity trader at Kühne & Heitz. I want to thank Kühne & Heitz for the opportunity to work in the trading environment and to learn what the use of derivatives is all about. A word of gratitude to my supervisor Drs. J.H. Gieskens for his quick reply, well experienced feedback that kept me sharp to different levels of the subject, and his availability even in the late hours after I finished work. -

A Practitioner's Guide to Structuring Listed Equity Derivative Securities

21 A Practitioner’s Guide to Structuring Listed Equity Derivative Securities JOHN C. BRADDOCK, MBA Executive Director–Investments CIBC Oppenheimer A Division of CIBC World Markets Corp., New York BENJAMIN D. KRAUSE, LLB Senior Vice President Capital Markets Division Chicago Board Options Exchange, New York Office INTRODUCTION Since the mid-1980s, “financial engineers” have created a wide array of instru- ments for use by professional investors in their search for higher returns and lower risks. Institutional investors are typically the most voracious consumers of structured derivative financial products, however, retail investors are increasingly availing themselves of such products through public, exchange- listed offerings. Design and engineering lie at the heart of the market for equity derivative securities. Through the use of computerized pricing and val- uation technology and instantaneous worldwide communications, today’s financial engineers are able to create new and varied instruments that address day-to-day client needs. This in turn has encouraged the development of new financial products that have broad investor appeal, many of which qualify for listing and trading on the principal securities markets. Commonly referred to as listed equity derivatives because they are listed on stock exchanges and trade under equity rules, these new financial products fuse disparate invest- ment features into single instruments that enable retail investors to replicate both speculative and risk management strategies employed by investment pro- fessionals. Options on individual common stocks are the forerunners of many of today’s publicly traded equity derivative products. They have been part of the 434 GUIDE TO STRUCTURING LISTED EQUITY DERIVATIVE SECURITIES securities landscape since the early 1970s.1 The notion of equity derivatives as a distinct class of securities, however, did not begin to solidify until the late 1980s. -

307439 Ferdig Master Thesis

Master's Thesis Using Derivatives And Structured Products To Enhance Investment Performance In A Low-Yielding Environment - COPENHAGEN BUSINESS SCHOOL - MSc Finance And Investments Maria Gjelsvik Berg P˚al-AndreasIversen Supervisor: Søren Plesner Date Of Submission: 28.04.2017 Characters (Ink. Space): 189.349 Pages: 114 ABSTRACT This paper provides an investigation of retail investors' possibility to enhance their investment performance in a low-yielding environment by using derivatives. The current low-yielding financial market makes safe investments in traditional vehicles, such as money market funds and safe bonds, close to zero- or even negative-yielding. Some retail investors are therefore in need of alternative investment vehicles that can enhance their performance. By conducting Monte Carlo simulations and difference in mean testing, we test for enhancement in performance for investors using option strategies, relative to investors investing in the S&P 500 index. This paper contributes to previous papers by emphasizing the downside risk and asymmetry in return distributions to a larger extent. We find several option strategies to outperform the benchmark, implying that performance enhancement is achievable by trading derivatives. The result is however strongly dependent on the investors' ability to choose the right option strategy, both in terms of correctly anticipated market movements and the net premium received or paid to enter the strategy. 1 Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction4 Problem Statement................................6 Methodology...................................7 Limitations....................................7 Literature Review.................................8 Structure..................................... 12 Chapter 2 - Theory 14 Low-Yielding Environment............................ 14 How Are People Affected By A Low-Yield Environment?........ 16 Low-Yield Environment's Impact On The Stock Market........ -

Forward Contracts and Futures a Forward Is an Agreement Between Two Parties to Buy Or Sell an Asset at a Pre-Determined Future Time for a Certain Price

Forward contracts and futures A forward is an agreement between two parties to buy or sell an asset at a pre-determined future time for a certain price. Goal To hedge against the price fluctuation of commodity. • Intension of purchase decided earlier, actual transaction done later. • The forward contract needs to specify the delivery price, amount, quality, delivery date, means of delivery, etc. Potential default of either party: writer or holder. Terminal payoff from forward contract payoff payoff K − ST ST − K K ST ST K long position short position K = delivery price, ST = asset price at maturity Zero-sum game between the writer (short position) and owner (long position). Since it costs nothing to enter into a forward contract, the terminal payoff is the investor’s total gain or loss from the contract. Forward price for a forward contract is defined as the delivery price which make the value of the contract at initiation be zero. Question Does it relate to the expected value of the commodity on the delivery date? Forward price = spot price + cost of fund + storage cost cost of carry Example • Spot price of one ton of wood is $10,000 • 6-month interest income from $10,000 is $400 • storage cost of one ton of wood is $300 6-month forward price of one ton of wood = $10,000 + 400 + $300 = $10,700. Explanation Suppose the forward price deviates too much from $10,700, the construction firm would prefer to buy the wood now and store that for 6 months (though the cost of storage may be higher). -

Sales Representatives Manual 2020

Sales Representatives Manual Volume 4 2020 Volume 4 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Overview of Derivatives Transactions ………… 1 Chapter 2 Products of Derivatives Transactions ……………99 Derivatives Transactions and Chapter 3 Articles of Association and ……………… 165 Various Rules of the Association Exercise (Class-1 Examination) ……………………………………… 173 Chapter 1 Overview of Derivatives Transactions Introduction ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 3 Section 1. Fundamentals of Derivatives Transactions ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 10 1.1 What Are Derivatives Transactions? ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 10 Section 2. Futures Transactions ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 10 2.1 What Are Futures Transactions? ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 10 2.2 Futures Price Formation ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 14 2.3 How to Use Futures Transactions ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 17 Section 3. Forward Transactions ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 24 3.1 What Are Forward Transactions? ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 24 Section 4. Option Transactions ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 25 4.1 What Are Options Transactions? ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 25 4.2 Options’ Price Formation ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 32 4.3 Characteristics of Options Premiums ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 36 4.4 Sensitivity of Premiums to the Respective Factors ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 38 4.5 How to Use Options ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 46 4.6 Option Pricing Theory ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 57 Section 5. Swap Transactions ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 63 5.1 What Are Swap Transactions? ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 63 Section 6. Risks in Derivatives Transactions ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 72 Conclusion ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ 82 Introduction Introduction 1. History of Derivatives Transactions Chapter 1 The term “derivatives” is used for financial instruments that “derive” from financial assets, meaning those that have securities such as shares or bonds as their underlying assets or financial transactions that use a reference indicator such as interest rates or exchange rates. Today the term “derivative” is used widely throughout society and not just on the financial markets. Although there has been criticism that they amplify financial risks and have a harmful impact on the Chapter 2 economy, derivatives are an indispensable requirement in supporting finance in the present age, and have become accepted as the leading edge of financial innovation. -

The Behaviour of Small Investors in the Hong Kong Derivatives Markets

Tai-Yuen Hon / Journal of Risk and Financial Management 5(2012) 59-77 The Behaviour of Small Investors in the Hong Kong Derivatives Markets: A factor analysis Tai-Yuen Hona a Department of Economics and Finance, Hong Kong Shue Yan University ABSTRACT This paper investigates the behaviour of small investors in Hong Kong’s derivatives markets. The study period covers the global economic crisis of 2011- 2012, and we focus on small investors’ behaviour during and after the crisis. We attempt to identify and analyse the key factors that capture their behaviour in derivatives markets in Hong Kong. The data were collected from 524 respondents via a questionnaire survey. Exploratory factor analysis was employed to analyse the data, and some interesting findings were obtained. Our study enhances our understanding of behavioural finance in the setting of an Asian financial centre, namely Hong Kong. KEYWORDS: Behavioural finance, factor analysis, small investors, derivatives markets. 1. INTRODUCTION The global economic crisis has generated tremendous impacts on financial markets and affected many small investors throughout the world. In particular, these investors feared that some European countries, including the PIIGS countries (i.e., Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain), would encounter great difficulty in meeting their financial obligations and repaying their sovereign debts, and some even believed that these countries would default on their debts either partially or completely. In response to the crisis, they are likely to change their investment behaviour. Corresponding author: Tai-Yuen Hon, Department of Economics and Finance, Hong Kong Shue Yan University, Braemar Hill, North Point, Hong Kong. Tel: (852) 25707110; Fax: (852) 2806 8044 59 Tai-Yuen Hon / Journal of Risk and Financial Management 5(2012) 59-77 Hong Kong is a small open economy. -

An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming John Jackson Ada Li Asani Sarkar Patricia Zobel Staff Report No. 557 March 2012 Revised October 2012 FRBNY Staff REPORTS This paper presents preliminary fi ndings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily refl ective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming, John Jackson, Ada Li, Asani Sarkar, and Patricia Zobel Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 557 March 2012; revised October 2012 JEL classifi cation: G12, G13, G18 Abstract This paper examines the over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives (IRD) market in order to inform the design of post-trade price reporting. Our analysis uses a novel transaction-level data set to examine trading activity, the composition of market participants, levels of product standardization, and market-making behavior. We fi nd that trading activity in the IRD market is dispersed across a broad array of product types, currency denominations, and maturities, leading to more than 10,500 observed unique product combinations. While a select group of standard instruments trade with relative frequency and may provide timely and pertinent price information for market partici- pants, many other IRD instruments trade infrequently and with diverse contract terms, limiting the impact on price formation from the reporting of those transactions. -

Half-Yearly Financial Report at 30 June 2019

Half-Yearly Financial Report at 30 June 2019 Contents Composition of the Corporate Bodies 3 The first half of 2019 in brief Economic figures and performance indicators 4 Equity figures and performance indicators 5 Accounting statements Balance Sheet 7 Income Statement 9 Statement of comprehensive income 10 Statements of Changes in Shareholders' Equity 11 Statement of Cash Flows 13 Report on Operations Macroeconomic situation 16 Economic results 18 Financial aggregates 22 Business 31 Operating structure 37 Significant events after the end of the half and business outlook 39 Other information 39 Notes to the Financial Statements Part A – Accounting policies 41 Part B – Information on the balance sheet 78 Part C – Information on the income statement 121 Part D – Comprehensive Income 140 Part E – Information on risks and relative hedging policies 143 Part F – Information on capital 155 Part H – Transactions with related parties 166 Part L – Segment reporting 173 Certification of the condensed Half-Yearly Financial Statements pursuant to Article 81-ter of 175 CONSOB Regulation 11971 of 14 May 1999, as amended Composition of the Corporate Bodies Board of Directors Chairperson Massimiliano Cesare Chief Executive Officer Bernardo Mattarella Director Pasquale Ambrogio Director Leonarda Sansone Director Gabriella Forte Board of Statutory Auditors Chairperson Paolo Palombelli Regular Auditor Carlo Ferocino Regular Auditor Marcella Galvani Alternate Auditor Roberto Micolitti Alternate Auditor Sofia Paternostro * * * Auditing Firm PricewaterhouseCoopers -

International Harmonization of Reporting for Financial Securities

International Harmonization of Reporting for Financial Securities Authors Dr. Jiri Strouhal Dr. Carmen Bonaci Editor Prof. Nikos Mastorakis Published by WSEAS Press ISBN: 9781-61804-008-4 www.wseas.org International Harmonization of Reporting for Financial Securities Published by WSEAS Press www.wseas.org Copyright © 2011, by WSEAS Press All the copyright of the present book belongs to the World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Editor of World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Press. All papers of the present volume were peer reviewed by two independent reviewers. Acceptance was granted when both reviewers' recommendations were positive. See also: http://www.worldses.org/review/index.html ISBN: 9781-61804-008-4 World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Preface Dear readers, This publication is devoted to problems of financial reporting for financial instruments. This branch is among academicians and practitioners widely discussed topic. It is mainly caused due to current developments in financial engineering, while accounting standard setters still lag. Moreover measurement based on fair value approach – popular phenomenon of last decades – brings to accounting entities considerable problems. The text is clearly divided into four chapters. The introductory part is devoted to the theoretical background for the measurement and reporting of financial securities and derivative contracts. The second chapter focuses on reporting of equity and debt securities. There are outlined the theoretical bases for the measurement, and accounting treatment for selected portfolios of financial securities. -

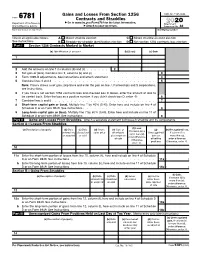

Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to for the Latest Information

Gains and Losses From Section 1256 OMB No. 1545-0644 Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form6781 for the latest information. 2020 Department of the Treasury Attachment Internal Revenue Service ▶ Attach to your tax return. Sequence No. 82 Name(s) shown on tax return Identifying number Check all applicable boxes. A Mixed straddle election C Mixed straddle account election See instructions. B Straddle-by-straddle identification election D Net section 1256 contracts loss election Part I Section 1256 Contracts Marked to Market (a) Identification of account (b) (Loss) (c) Gain 1 2 Add the amounts on line 1 in columns (b) and (c) . 2 ( ) 3 Net gain or (loss). Combine line 2, columns (b) and (c) . 3 4 Form 1099-B adjustments. See instructions and attach statement . 4 5 Combine lines 3 and 4 . 5 Note: If line 5 shows a net gain, skip line 6 and enter the gain on line 7. Partnerships and S corporations, see instructions. 6 If you have a net section 1256 contracts loss and checked box D above, enter the amount of loss to be carried back. Enter the loss as a positive number. If you didn’t check box D, enter -0- . 6 7 Combine lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Short-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 40% (0.40). Enter here and include on line 4 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. See instructions . 8 9 Long-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 60% (0.60). Enter here and include on line 11 of Schedule D or on Form 8949.