MSE3 Ch12 Airmasses & Fronts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Disease and Air Quality in a Changing Climate by Kim Frauhammer

YP Perspective Global Disease and Air Quality in a Changing Climate by Kim Frauhammer Through the lens of the current global pandemic, a look at some of the existing challenges, such as environmental degradation, decreasing air quality, and climate change, that continue to put the human population at risk. 2020 has already been a year to remember, defined by the Seasonality of the Virus novel Coronavirus and its far-reaching effects on our health With how expansive this virus has proven to be, examining and economy. This global pandemic has restructured our all methods of transport is vital to understanding the future lives, while existing global challenges that continue to put the of global diseases. According to the U.S. Global Change human population at risk remain. Environmental degradation, Research Program, a set of “vulnerability factors” determine decreasing air quality, and climate change continue to expose whether someone is at risk for adverse health outcomes: the human population to higher risks of illness and loss of exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity.1 The climate and resources. COVID-19 has provided us with a unique window environment are a part of all three. The virus first emerged into identifying these underlying risks and highlights the and spread rampantly during the Northern Hemisphere benefits between preserving the future of not only our Winter and there is scientific evidence to point to why. health, but our environment as well. Humidity is the greatest factor. em • The Magazine for Environmental Managers • A&WMA • August 2020 YP Perspective In the midlatitudes of the Northern Hemisphere (broadly be - Recent research from Harvard University cites that people tween 30 and 60 degrees), the atmosphere cools down as the who live in areas of poor air quality are more likely to die Earth is tilted farther away from the sun during the winter. -

An Air Stagnation Index to Qualify Extreme Haze Events in Northern China

OCTOBER 2018 F E N G E T A L . 3489 An Air Stagnation Index to Qualify Extreme Haze Events in Northern China JIN FENG Institute of Urban Meteorology, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing, China, and National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado JIANNONG QUAN Institute of Urban Meteorology, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing, China HONG LIAO Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Environment Monitoring and Pollution Control, Collaborative Innovation Center of Atmospheric Environment and Equipment Technology, School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, China YANJIE LI State Key Laboratory of Numerical Modeling for Atmospheric Sciences and Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China XIUJUAN ZHAO Institute of Urban Meteorology, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing, China (Manuscript received 27 November 2017, in final form 18 June 2018) ABSTRACT Stagnation weather affects atmospheric diffusion ability, and hence causes the occurrence of haze events, which have been happening frequently in northern China (NC). This work puts forward an air stagnation index (ASITS) to characterize the stagnation weather in NC, in which the processes of ventilation, vertical diffusion, and wet deposition potency are concerned. ASITS can be applied to analyze air stagnation conditions with daily to monthly time scale. It is shown that the ASITS and particulate matter smaller than 2.5 mmindiameter(PM2.5) concen- trations own similar lognormal probability distribution functions on both daily and monthly time scales. And the correlation analyses between the ASITS and PM2.5 concentrations indicate that the ASITS can reflect the monthly and daily variations in PM2.5 concentrations in NC. -

Asthma Aggravation, Combustion, and Stagnant Air

466 Thorax 2000;55:466–470 Asthma aggravation, combustion, and stagnant air Gary Norris, Timothy Larson, Jane Koenig, Candis Claiborn, Lianne Sheppard, Dennis Finn Abstract meteorology with a knowledge of specific air Background—The relationship between pollution point sources. current concentrations of ambient air Other studies have combined meteorology pollution and adverse health eVects is with chemical composition of particulate mat- controversial. We report a meteorological ter. For instance, factor analysis with a varimax index of air stagnation that is associated rotation of the particulate matter composition with daily visits to the emergency depart- collected from 1957 to 1961 from 30 cities ment for asthma in two urban areas. across the USA found seven factors represent- Methods—Data on daily values of a stag- ing heavy industry or steel production, internal nation persistence index and visits to the combustion engines, coal combustion, possible emergency department for asthma were gas production, a zinc-tin factor, plating, and collected for approximately two years in copper.6 Gatz7 included meteorological vari- Spokane, Washington, USA and for 15 ables (mean wind speed, maximum wind months in Seattle, Washington, USA. The speed, ventilation rate, wind direction, rain) stagnation persistence index represents along with the composition of particulate mat- the number of hours during the 24 hour ter in a factor analysis to help identify sources. day when surface wind speeds are less In that study wind direction was the only than the annual hourly median value, an meteorological variable that was correlated index readily available for most urban with particulate matter concentration. 8 areas. Associations between the daily Thurston and Spengler used factor analysis stagnation persistence index and daily with a varimax rotation separately on particu- emergency department visits for asthma late matter composition and meteorological were tested using a generalised additive parameters. -

Key Points in Air Pollution Meteorology

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Key Points in Air Pollution Meteorology Isidro A. Pérez * , Mª Ángeles García , Mª Luisa Sánchez, Nuria Pardo and Beatriz Fernández-Duque Department of Applied Physics, Faculty of Sciences, University of Valladolid, Paseo de Belén, 7, 47011 Valladolid, Spain; [email protected] (M.Á.G.); [email protected] (M.L.S.); [email protected] (N.P.); [email protected] (B.F.-D.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 September 2020; Accepted: 9 November 2020; Published: 11 November 2020 Abstract: Although emissions have a direct impact on air pollution, meteorological processes may influence inmission concentration, with the only way to control air pollution being through the rates emitted. This paper presents the close relationship between air pollution and meteorology following the scales of atmospheric motion. In macroscale, this review focuses on the synoptic pattern, since certain weather types are related to pollution episodes, with the determination of these weather types being the key point of these studies. The contrasting contribution of cold fronts is also presented, whilst mathematical models are seen to increase the analysis possibilities of pollution transport. In mesoscale, land–sea and mountain–valley breezes may reinforce certain pollution episodes, and recirculation processes are sometimes favoured by orographic features. The urban heat island is also considered, since the formation of mesovortices determines the entry of pollutants into the city. At the microscale, the influence of the boundary layer height and its evolution are evaluated; in particular, the contribution of the low-level jet to pollutant transport and dispersion. -

10-519 WFO Air Quality Products Specification

Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE INSTRUCTION 10-519 October 10, 2017 Operations and Services Public Weather Services, NWSPD 10-5 WFO AIR QUALITY PRODUCTS SPECIFICATION NOTICE: This publication is available at: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/. OPR: W/AFS21 (J. Ferrell) Certified by: W/AFS21 (M. Hawkins) Type of Issuance: Routine SUMMARY OF REVISIONS: This directive supersedes NWSI 10-519, “WFO Air Quality Products Specification,” dated August 31, 2013. Changes made to reflect NWS Headquarters reorganization effective April 1, 2015. No content changes were made. Signed 9/26/2017 Andrew D. Stern Date Director Analyze, Forecast, and Support Office NWSI 10-519 October 10, 2017 WFO Air Quality Products Specification Table of Contents: Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Air Quality Statement (AQI) 3 2.1 Mission Connection 3 2.2 Issuance Guidelines 3 2.2.1 Creation Software 3 2.2.2 Issuance Criteria 3 2.2.2.1 Routine Issuances 3 2.2.3 Issuance Time 4 2.2.4 Valid Time 4 2.2.5 Product Expiration Time 4 2.3 Technical Description 4 2.3.1 Universal Geographic Code (UGC) Type 4 2.3.2 Mass News Disseminator (MND) Broadcast Instruction Line 4 2.3.3 MND Product Type Line 4 2.3.4 Content 5 2.4 Updates and Corrections 5 3. Air Quality Alert Message (AQA) 5 3.1 Mission Connection 5 3.2 Issuance Guidelines 5 3.2.1 Creation Software 5 3.2.2 Issuance Criteria 5 3.2.2.1 Non-Routine Issuances 6 3.2.3 Issuance Time 6 3.2.4 Valid Time 6 3.2.5 Product Expiration Time 6 3.3 Technical Description 6 3.3.1 UGC Type 6 3.3.2 MND Broadcast Instruction Line 6 3.3.3 MND Product Type Line 6 3.3.4 Content 7 3.4 Updates and Corrections 7 APPENDIX – Product Examples and Air Quality Resources A-1 2 NWSI 10-519 October 10, 2017 1. -

Meteorology-Driven Variability of Air Pollution (PM1

Meteorology-driven variability of air pollution (PM1) revealed with explainable machine learning Roland Stirnberg1,2, Jan Cermak1,2, Simone Kotthaus3, Martial Haeffelin3, Hendrik Andersen1,2, Julia Fuchs1,2, Miae Kim1,2, Jean-Eudes Petit4, and Olivier Favez5 1Institute of Meteorology and Climate Research, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany 2Institute of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany 3Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, École Polytechnique, CNRS, Institut Polytechnique de Paris, Palaiseau, France 4Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, CEA/Orme des Merisiers, Gif sur Yvette, France 5Institut National de l’Environnement Industriel et des Risques, Parc Technologique ALATA, Verneuil en Halatte, France Correspondence: Roland Stirnberg ([email protected]) Abstract. Air pollution, in particular high concentrations of particulate matter smaller than 1 µm in diameter (PM1), continues to be a major health problem, and meteorology is known to substantially influence atmospheric PM concentrations. How- ever, the scientific understanding of the ways by which complex interactions of meteorological factors lead to high pollution episodes is inconclusive RS:, as the effects of meteorological variables are not easy to separate and quantify. In this study, a novel, data-driven 5 approach based on empirical relationships is used to characterise, and better understand the meteorology-driven component of PM1 variability. A tree-based machine learning model is set up to reproduce concentrations of speciated PM1 at a suburban site southwest of Paris, France, using meteorological variables as input features. RS:The model is able to capture the majority 2 of occurring variance of mean afternoon total PM1 concentrations (coefficient of determination (R ) of 0.58), with model performance depending on the individual PM1 species predicted. -

Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Imapct Study

Van Buren Boulevard Commercial Development Center Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Impact Study City of Jurupa Valley, CA Prepared for: Alex Flores Control Management, Inc. PO Box 7398 La Verne, CA 91750 Prepared by: MD Acoustics, LLC Mike Dickerson, INCE 1197 Los Angeles Ave, Ste C-256 Simi Valley, CA 93065 Date: 10/23/2019 Van Buren Boulevard Commercial Development Center Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Impact Study City of Jurupa Valley, CA TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose of Analysis and Study Objectives 1 1.2 Project Summary 1 1.2.1 Site Location 1 1.2.2 Project Description 1 1.2.3 Sensitive Receptors 2 1.3 Executive Summary of Findings and Mitigation Measures 2 2.0 Regulatory Framework and Background .................................................................................. 7 2.1 Air Quality Regulatory Setting 7 2.1.1 National and State 7 2.1.2 South Coast Air Quality Management District 9 2.2 Greenhouse Gas Regulatory Setting 12 2.2.1 International 12 2.2.2 National 12 2.2.3 California 13 2.2.4 South Coast Air Quality Management District 19 2.2.5 City of Jurupa Valley 20 3.0 Setting ................................................................................................................................... 23 3.1 Existing Physical Setting 23 3.1.1 Local Climate and Meteorology 23 3.1.2 Local Air Quality 24 3.1.3 Attainment Status 27 3.2 Greenhouse Gases 28 4.0 Modeling Parameters and Assumptions................................................................................. 30 4.1 Construction 30 4.2 Operations 31 4.3 Localized Construction Analysis 32 4.4 Localized Operational Analysis 33 5.0 Thresholds of Significance ..................................................................................................... -

Corydon Gateway Development Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Impact Study City of Lake Elsinore, CA

Appendix A Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Impact Study AZ Office CA Office 4960 S. Gilbert Rd, Suite 1-461 1197 Los Angeles Ave, Suite C-256 Chandler, AZ 85249 Simi Valley, CA 93065 p. (602) 774-1950 p. (805) 426-4477 www.mdacoustics.com October 21, 2020 Mr. Brandon Humann Rancho Development Partners, LLC 25425 Jefferson Avenue, Ste 101 Murrieta, CA 92562 Subject: Corydon Gateway Development – Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Impact Study, City of Murrieta, , City of Lake Elsinore, CA – Memo #1 Dear Mr. Humann: MD Acoustics, LLC (MD) has been working with RED Corydon, LLC and team as it relates to the Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas (AQ/GHG) study for the Cordon Gateway Development project located at the southwest corner of Mission Trail and Lemon Street, in the City of Lake Elsinore, CA. MD competed a revised AQ/GHG study 9/14/2020, which addresses the comments prepared by Helix. In addition, MD provided response to comments for those comments provided. The intent of this memo is to address the slight difference between the project’s land uses and the ones identified in the AQ/GHG report. Originally, the project showed a drive-thru fast food on parcel 4. Now the new site plan illustrates a tire store. Although the project’s land uses have changed since the preparation of the report, the land uses/assumptions used in the modeling and analysis provide a conservative analysis as the trip generation rates for drive-thru restaurants are higher than for tire stores. MD is pleased to provide this memo. -

58.01.01, Rules for the Control of Air

IDAPA 58 – DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Air Quality Division 58.01.01 – Rules for the Control of Air Pollution in Idaho To whom does this rule apply? This rule applies to the general public and businesses that emit air pollution. What is the purpose of this rule? This rule provides for the control of air pollution in Idaho. What is the legal authority for the agency to promulgate this rule? This rule implements the following statutes passed by the Idaho Legislature: Health and Safety - Environmental Quality: • Section 39-105, Idaho Code – Powers and Duties of the Director • Section 39-107, Idaho Code – Board-Composition – Officers – Compensation – Powers – Subpoena – Depositions – Review - Rules • Section 39-114(4), Idaho Code – Open Burning of Crop Residue • Section 39-115(3), Idaho Code – Pollution Source Permits • Section 39-116B, Idaho Code – Vehicle Inspection and Maintenance Program Who do I contact for more information on this rule? Paula Wilson Department of Environmental Quality 1410 N. Hilton Boise, ID 83706 Phone: (208) 373-0418 Fax: (208) 373-0481 Email: [email protected] www.deq.idaho.gov Zero-Based Regulation Review – 2022 for Rulemaking and 2023 Legislative Review Table of Contents IDAPA 58 – DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 58.01.01 – Rules for the Control of Air Pollution in Idaho 000. Legal Authority. ............................................................................................... 10 001. Title And Scope. ............................................................................................. -

Nashville 1999 Field Study Science Plan

NASHVILLE 1999 FIELD STUDY SCIENCE PLAN DRAFT October 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Proposed Research 7 Primary PM and PM Precursor Emissions 11 PBL Dynamics 13 Ozone Production Efficiency 19 Characterization of Loss Processes 23 VOC Contribution to Ozone and PM Formation 27 Fine Particulate Matter Formation and Characterization 31 Nighttime Chemistry and Dynamics 37 Instrumented Aircraft 41 Ground-Based Measurements 61 Tracer Release 67 References 69 Appendix A Ð Southern Center for the Integrated Study of Secondary Air Pollutants (SCISSAP) A-1 Appendix B Ð The National Parks Service Enhanced Monitoring Network B-1 Appendix C Ð TVA/EPRI/NPS Enhanced Monitoring Site GSMNP C-1 Appendix D Ð SEARCH D-1 Nashville 99 Science Plan INTRODUCTION The SOS Paradigm and commercial organizations can manage the accumulation of ozone and other photochemical The oxidant-management approaches being used oxidants in the atmosphere, and decrease the during the 1980s were based largely on scientific injurious effects of these airborne chemicals in findings, air quality models, and related air quality various urban and rural areas. management tools from research conducted in southern California and the urban megalopolis in the northeastern United States. Few scientific studies had SOS Research been conducted in the South. In the late 1980s, however, studies began to emerge that pointed to the Prior to the late 1980Õs, biogenic hydrocarbons were SouthÕs unique air quality management problems. believed to play little or no role in ozone formation in -

Iv-1 Acid Rain Action Stage Advection Advisory Ahps Air

Cloud or rain droplets containing pollutants or oxides of sulfur and nitrogen to ACID RAIN make them acidic. The level of a river or stream that may cause minor flooding, and at which ACTION STAGE concerned interests should take action. Also called the Warning Stage. The horizontal transport of air or atmospheric properties. Commonly used with ADVECTION temperatures and moisture (e.g., “warm air advection” or “moisture advection”). Issued for weather situations that cause significant inconveniences but do not ADVISORY meet warning criteria and, if caution is not exercised, could lead to situations that may threaten life and/or property. Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service. A web-based suite of graphical AHPS forecast products. They display the magnitude and uncertainty of the occurrence of floods or droughts, from hours to days and months, in advance. A large body of air having similar horizontal temperature and moisture AIR MASS characteristics. A meteorological situation in which there is a major buildup of air pollution in the atmosphere. This usually occurs when an air mass is parked over the AIR STAGNATION same area for several days. During this time, the light winds cannot “cleanse” the buildup of smoke, dust, gases, and other industrial air pollution. A low-pressure system that moves out of southwest Canada and mainly ALBERTA affects the Plains, Midwest, and Great Lakes region. Usually accompanied by CLIPPER light snow, strong winds, and colder temperatures. Another variation of the same system is called a “Saskatchewan Screamer”. ALTOCUMULUS Mid-altitude clouds with a cumuliform shape. ALTOSTRATUS Mid-altitude clouds with a flat, sheet-like appearance. -

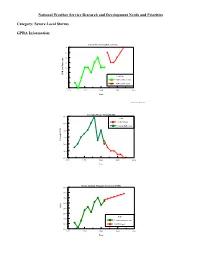

National Weather Service Research and Development Needs and Priorities

National Weather Service Research and Development Needs and Priorities Category: Severe Local Storms GPRA Information: Annual Mean Tornado Lead Time 14 13 12 11 10 9 TOR lead time, min Lead Time 8 TOR lead time Actual 7 TOR lead time Goal 6 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Year GPRA_REVISED_FEB02_DM.PDW Tornado Mean Annual FAR 80.0 FAR TOR FAR goal 78.0 Tornado FAR actual 76.0 74.0 Tornado FAR Tornado 72.0 70.0 68.0 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Year Mean Annual Tornado Accuracy (POD) 80.0 75.0 70.0 65.0 POD 60.0 55.0 POD 50.0 Tornado accuracy actual 45.0 TOR POD goal 40.0 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Year Statement of Need: Research and development are needed to improve warning, forecast accuracy and lead times for severe local storms (e.g., large hail, severe thunderstorms, weak tornadoes, and lightning). Priority: Justification: Each year, hundreds of lives and billions of dollars are lost due to severe storms, floods and other natural events. However, research and development is needed to meet GPRA goals in this category. The current linear lead time trend does not favor reaching the goal within the next decade. The 2001 tornado lead time goal was 12 minutes. Actual performance was 10 minutes. By 2008, the tornado lead time goal increases to 15 minutes. The 2001 tornado probability of detection (POD) goal was .68. Actual performance was .67. By 2008, the POD goal increases to .74. The 2001 tornado mean annual false alarm ratio (FAR) goal was .74.