Composition's Eye/Orpheus's Gaze/ Cobain's Journals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home

WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER A) Identification Historic Name: Cobain, Donald & Wendy, House Common Name: Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home Address: 1210 E. First Street City: Aberdeen County: Grays Harbor B) Site Access (describe site access, restrictions, etc.) The nominated home is located mid block near the NW corner of E 1st Street and Chicago Avenue in Aberdeen. The home faces southeast one block from the Wishkah River adjacent to an alleyway. C) Property owner(s), Address and Zip Name: Side One LLC. Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City: Ocean Shores State: WA Zip: 98569 D) Legal boundary description and boundary justification Tax No./Parcel: 015000701700 - 11 - Residential - Single Family Boundary Justification: FRANCES LOT 17 BLK 7 / MAP 1709-04 FORM PREPARED BY Name: Lee & Danielle Bacon Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City / State / Zip: Ocean Shores, WA 98569 Phone: 425.283.2533 Email: [email protected] Nomination June 2021 Date: 1 WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER E) Category of Property (Choose One) building structure (irrigation system, bridge, etc.) district object (statue, grave marker, vessel, etc.) cemetery/burial site historic site (site of an important event) archaeological site traditional cultural property (spiritual or creation site, etc.) cultural landscape (habitation, agricultural, industrial, recreational, etc.) F) Area of Significance – Check as many as apply The property belongs to the early settlement, commercial development, or original native occupation of a community or region. The property is directly connected to a movement, organization, institution, religion, or club which served as a focal point for a community or group. -

A Case Study of Kurt Donald Cobain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) A CASE STUDY OF KURT DONALD COBAIN By Candice Belinda Pieterse Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University December 2009 Supervisor: Prof. J.G. Howcroft Co-Supervisor: Dr. L. Stroud i DECLARATION BY THE STUDENT I, Candice Belinda Pieterse, Student Number 204009308, for the qualification Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology, hereby declares that: In accordance with the Rule G4.6.3, the above-mentioned treatise is my own work and has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Signature: …………………………………. Date: …………………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several individuals that I would like to acknowledge and thank for all their support, encouragement and guidance whilst completing the study: Professor Howcroft and Doctor Stroud, as supervisors of the study, for all their help, guidance and support. As I was in Bloemfontein, they were still available to meet all my needs and concerns, and contribute to the quality of the study. My parents and Michelle Wilmot for all their support, encouragement and financial help, allowing me to further my academic career and allowing me to meet all my needs regarding the completion of the study. The participants and friends who were willing to take time out of their schedules and contribute to the nature of this study. Konesh Pillay, my friend and colleague, for her continuous support and liaison regarding the completion of this study. -

A Denial the Death of Kurt Cobain the Seattle Police Department

A Denial The Death of Kurt Cobain The Seattle Police Department Substandard Investigation & The Repercussions to Justice by Bree Donovan A Capstone Submitted to The Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University, New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies Under the direction of Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo and approved by _________________________________ Capstone Director _________________________________ Program Director Camden, New Jersey, December 2014 i Abstract Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) musician, artist songwriter, and founder of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band, Nirvana, was dubbed, “the voice of a generation”; a moniker he wore like his faded cardigan sweater, but with more than some distain. Cobain‟s journey to the top of the Billboard charts was much more Dickensian than many of the generations of fans may realize. During his all too short life, Cobain struggled with physical illness, poverty, undiagnosed depression, a broken family, and the crippling isolation and loneliness brought on by drug addiction. Cobain may have shunned the idea of fame and fortune but like many struggling young musicians (who would become his peers) coming up in the blue collar, working class suburbs of Aberdeen and Tacoma Washington State, being on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine wasn‟t a nightmare image. Cobain, with his unkempt blond hair, polarizing blue eyes, and fragile appearance is a modern-punk-rock Jesus; a model example of the modern-day hero. The musician- a reluctant hero at best, but one who took a dark, frightening journey into another realm, to emerge stronger, clearer headed and changing the trajectory of his life. -

Behind the Music

Q&A BEHIND THE MUSIC It’s crazy to think that this year marks the 20th Anniversary of Kurt Cobain’s passing – a true game-changer in our industry, and a man who, in many ways, revolutionised music, inadvertently spawning a whole new scene. Nevermind is a seminal record, and its success was the catalyst for record labels’ mission impossible, the search for ‘the next Nirvana’. Although he might not have known it at the time, those 16 days recording Nevermind would change Butch Vig’s career forever. It paved the way for a remarkable musical journey, the production of a string of hit records for supergroups such as The Smashing Pumpkins, The Foo Fighters, and many more... Not to mention Garbage, Vig’s own band, which has enjoyed more than 17 million record sales over the last two decades. This legend of the game reveals some of his trade secrets, and shares some fond, unforgettable memories... Your career speaks for itself, but first up, how did it all begin for you? Well, I played in bands in high school in a small town in Wisconsin, and then I went to University in Madison. I started getting into the local music scene, and joined a band, which was sort of a power pop, new wave band called Spooner; and Duke [Erikson] from Garbage was the guitarist and lead singer at the time. I also got a degree in film, and ended up doing a lot of music for film; a lot of synth, and abstract music, and that’s where I kind of got the recording bug. -

Dave Grohl's Growth Mindset

! Handout 2 - Dave Grohl’s Growth Mindset To some, Dave Grohl is the drummer from the groundbreaking Seattle “Grunge” band Nirvana. Other music fans likely know him as the guitarist, vocalist, frontman, and songwriter of the arena- filling band, Foo Fighters. Still others that have seen Grohl on the HBO series Sonic Highways or the documentary Sound City may recognize him as a music historian and film director. The truth is that Dave Grohl is all of the above. Thinking back to his childhood during an episode of the Sonic Highways series, Grohl remembers his artistic “light bulb” turning on during a family vacation to Chicago. Grohl, only twelve at the time, accompanied a cousin to a local Punk concert. It was awesome. He left the show inspired, asking himself, “why can’t I do this?” Then, he realized he could. Once home in Springfield, VA, a Beltway suburb about thirteen miles from the White House, the young Grohl tapped into D.C.’s thriving Punk scene. He befriended members of the local music community such as Ian MacKaye, a go-getter who played bass in Teen Idles, sang in Minor Threat, and later handled guitar and vocals in Fugazi, all while co-founding the Dischord Records label. In the mid and late 1980s, the major record labels, radio, and MTV--basically all the national tastemakers--were mostly focused on Glam Rock, Synth Pop, and Michael Jackson. D.C. Punk wasn’t even on their radar. But, rather than get discouraged or bitter about the lack of outside investment, many in the D.C. -

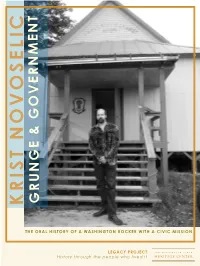

Krist Novoselic

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

Rewriting in Neil Gaiman´S Graphic Novel Sandman

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature Rewriting in Neil Gaiman´s Graphic Novel Sandman Bachelor thesis Šárka Nygrýnová Brno, April 2009 Supervisor: Mgr. Pavla Buchtová Hereby I declare that I have worked on my thesis on my own and that no other sources except for those enumerated in bibliography were used. ................................................... Šárka Nygrýnová 2 I would like to thank Mgr. Pavla Buchtová for her kind guidance and valuable advice she provided to me. 3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................5 Opening.......................................................................................................................6 1. Postmodernisms......................................................................................................7 1.1 The beginning of postmodernisms............................................................7 1.2 The history of postmodernisms.................................................................8 1.3 Basic distinction between modernism and postmodernisms...................10 1.4 Devices of postmodernisms......................................................................11 1.4.1 Reading and interpretation.............................................11 1.4.2 Distribution....................................................................11 1.5 The death of postmodernisms...................................................................12 -

Adaptation and Narrative Structure in the Orpheus Myth Ryan Cadrette

Tracing Eurydice: Adaptation and Narrative Structure in the Orpheus Myth Ryan Cadrette Master’s Thesis in The Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Media Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2013 © Ryan Cadrette, 2013 iii Abstract Tracing Eurydice: Adaptation and Narrative Structure in the Orpheus Myth Ryan Cadrette The primary purpose of this thesis is to postulate a working method of critical inquiry into the processes of narrative adaptation by examining the consistencies and ruptures of a story as it moves across representational form. In order to accomplish this, I will draw upon the method of structuralist textual analysis employed by Roland Barthes in his essay S/Z to produce a comparative study of three versions of the Orpheus myth from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. By reviewing the five codes of meaning described by Barthes in S/Z through the lens of contemporary adaptation theory, I hope to discern a structural basis for the persistence of adapted narrative. By applying these theories to texts in a variety of different media, I will also assess the limitations of Barthes’ methodology, evaluating its utility as a critical tool for post-literary narrative forms. iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Peter van Wyck, for his reassurance that earlier drafts of this thesis were not necessarily indicative of insanity, and, hopefully, for his forgiveness of my failure to incorporate all of his particularly insightful feedback. I would also like to thank Matt Soar and Darren Wershler for agreeing to actually read the peculiar monstrosity I have assembled here. -

Spawn Origins: Book 4 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SPAWN ORIGINS: BOOK 4 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Todd McFarlane,Alan Moore | 325 pages | 27 Sep 2011 | Image Comics | 9781607064374 | English | Fullerton, United States Spawn Origins: Book 4 PDF Book Spawn Origins TPB 1 - 10 of 20 books. Dissonance Volume 1. I love seeing Malebolgia and listening to Count Cogliostro. Includes the classic "Christmas" issue as well as the double-sized issue 50! Revisit stories of deception and betrayal,with Al's former boss, Jason Wynn, in the center of it all. Jun 08, Julian rated it it was ok Shelves: comic-books , spawn. Average rating 3. I was aware of Neil Gaiman's legal battles over Angela, Cogliostro and Medieval Spawn but I had no idea the extent to which later issues would continually refer back to ideas which were outsourced. View basket. Showing I dunno they don't tell you much and it's a odd place to start. Another darn good volume of Spawn. Spawn: Origins, Volume 9. United Kingdom. And for years, the passengers and crew of the vessel Orpheus found the endless void between realities to be a surprisingly peaceful home. Spawn: Hell On Earth. Then the last one is kind of a weird one about Spawn seeing a different outlook on things and maybe not being a complete dick to everyone he meets all the time. Anyway next 4 issues begin the "Hunt" which has basically put Terry, Spawn's friend, in the middle of a all out war and everyone wants him done. Brit, Volume 1: Old Soldier. Seller Inventory ADI The guest writers on the early Spawn titles Moore, Morrison and Gaiman really hit it out of the park by establishing interesting lore that had implications for the whole Spawn universe. -

Stagger Lee How Violent Nostalgia Created an American Folk Song Standard

Essay Stagger Lee How Violent Nostalgia Created an American Folk Song Standard Duncan Williams University of York Tradition ist die Weitergabe des Feuers und nicht die Anbetung der Asche. ~ Attr. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911, German composer) Tradition is tending the flame, not worshipping the ashes (Translation by author) Tending the Flame There is a long tradition of storytelling in folksong. Before methods for transcribing and later for recording definitive versions existed, the oral tradition was used to pass on tales and deeds. And, as anyone familiar with ‘Chinese whispers’ will know, this process is not always accurate. Even when transcription methods had become available, the accuracy of the record can be questioned, as is the case in Sabine Bearing-Gould (1834-1924), an 18th century Anglican reverend, perhaps most famous for his earnest documentation of werewolves (Baring-Gould 1973), as well as many collections of English folk song, which were often unsurprisingly edited from the pious perspective of a religious man of the time, likely due to the collectors profession. Often, such songs are cautionary or moral tales, and thus the process of collecting and editing can change an oral history dramatically. This essay will consider how one such instance, the song Stagger Lee, reflects changing attitudes of the audience and the narrator towards violence and masculinity in its portrayal of an initially real-world, and later supernatural, violent protagonist. How, and why this paean to violence, with its fetishistic vision of extreme masculinity, has become something of a standard in the American folk canon. It considers both the retelling of Stagger Lee’s tale in song, and subsequent appropriation by cinema in depictions of race, sex, and violence as admirable or heroic qualities.