Paradoxes of Ghettoization: Juhapura 'In' Ahmedabad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Model Code Casts Shadow on World Heritage Week Celebrations

2/7/2020 Model Code casts shadow on World Heritage Week celebrations Claim your 100 coins now ! Sign Up HOME PHOTOS INDIA ENTERTAINMENT SPORTS WORLD BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY LIFESTYLE Sexuality Happy Rose Valentine's Day 2020: Day 2020: From Share these Rose Day to WhatsApp Promise Day, messages, here's f... $S14M.99S, couplets wit$h10.1..9. 9 $99.99 NADA bans Indian$15.29 boxer Sumit San$gwan29.99 Propose Day 2020: Best This Valentine's Day, surprise your bae for a year for failing dope test WhatsApp messages, with 'pizza ring'; h... Diwali 2019: 5 DIY ways to use fairy lights SMS, couplets, quotes to Rose Day 2020: From Red to peach, here's for decoration this Diwali express... what colours of rose represen... TRENDING# Delhi Elections 2020 CAA protests Ind vs NZ Nirbhaya JNU Home » India » Ahmedabad Model Code casts shadow on World Heritage Week celebrations The civic body is taking steps on how to ensure that the week-long World Heritage Week celebration is a memorable one in wake of the Model Code of Conduct Bhadra Fort Bhadra Fort, which is a heritage site in the city The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation is all geared up to celebrate the World Heritage Week from November 19, the rst after it was declared as SHARE the rst World Heritage City of India by the UNESCO on July 8. However, AMC which had to shelve its plan to observe fortnight-long celebration beginning August 1 to showcase its achievement, in the wake WRITTEN BY of heavy rains and subsequent widespread oods across the state does n want to take any chances this time. -

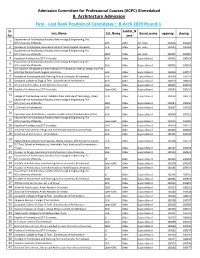

B. Architecture Admission First - Last Rank Position of Candidates :: B.Arch 2020 Round-1 Sr

Admission Committee for Professional Courses (ACPC) Ahmedabad B. Architecture Admission First - Last Rank Position of Candidates :: B.Arch 2020 Round-1 Sr. SubCat_N Inst_Name Cat_Name Board_name opening closing No. ame Department of Architecture,Faculty of technology & Engineering,The 1 M.S.University of Baroda GEN Other ALL India 300001 300001 2 Institute of Architecture, Hemchandracharya North Gujarat University GEN Other ALL India 300003 300004 Department of Architecture,Faculty of technology & Engineering,The 3 M.S.University of Baroda SEBC Other ALL India 300087 300087 4 Faculty of Architecture,CEPT University GEN Other Gujarat Board 100001 100048 Department of Architecture,Faculty of technology & Engineering,The 5 M.S.University of Baroda GEN Other Gujarat Board 100002 100059 Shri Gijubhai Chhaganbhai Patel Institute of Architecture, Interior Design and Fine 6 Arts,Veer Narmad South Gujarat University GEN Other Gujarat Board 100003 100717 7 Institute of Architecture and Planning, Nirma University, Ahmedabad GEN Other Gujarat Board 100004 100113 8 Sarvajanik College Of Engg. & Tech. ,Surat faculty of Architecture GEN Other Gujarat Board 100019 100245 9 School of Architecture, Anant National University GEN Other Gujarat Board 100032 100219 10 Faculty of Architecture,CEPT University Open-EWS Other Gujarat Board 100054 100115 11 College of Architecture, Sardar Vallabhai Patel Institute of Technology, Vasad. GEN Other Gujarat Board 100060 100731 Department of Architecture,Faculty of technology & Engineering,The 12 M.S.University of Baroda -

DOWNLOAD JBT Syllabus

SYLLABI AND COURSES OF STUDY DIPLOMA IN ELEMENTARY EDUCATION (EFFECTIVE from 2013-2014) Price Rs ----------- For Admission to the 2-year Diploma in Elementary Education Syllabi And Courses of Study The Jammu and Kashmir State Board of School Education First Edition 2013 For any other information or clarification please contact: Secretary Jammu and Kashmir Board of School Education, Srinagar/ Jammu. Telephone No’s: Srinagar: 0194-2491179, Fax 0194-2494522 (O) Telephone No’s: Jammu: 0191-2583494, Fax 0191-2585480. Published by the State Board of School Education and Printed at: -------------------------------------------------- The Jammu and Kashmir State Board of School Education (Academic Division, By-pass Bemina, Srinagar -1900 18 and Rehari Colony, Jammu Tawi-180 005) CONTENTS S.No Description Page No. 1. Preamble and Objectives of Elementary Education 2. Duration of the Course 3. Eligibility 4. Medium of Instruction and Examination 5. Submission of Applications 6. Admission in the Institution 7. Monitoring and Evaluation of Teacher Education Program 8. Curriculum and its Transaction 9. Teaching Practice 10. General Scheme of Examination 11. Pass Criteria 12. Curriculum structure for 1st and 2nd Year The Curriculum is based on the following courses 1. Child studies a. Childhood and the development of children b. Cognition learning and Socio-Cultural Context 2. Contemporary Studies b. Diversity Gender and Inclusive Education 3. Education Studies a. Education, Society, Culture and Learners b. Towards understanding the Self c. Teacher Identity and School Culture d .School Culture Leadership and Change 4. Pedagogic Studies a. Pedagogy across the Curriculum b. Understanding Language and Literacy c. Pedagogy of Environmental Studies d. -

Beatrice Catanzaro Documentation MAMMALITURCHI Temporary Public Installation Wood Structure + 431 Lights

Beatrice Catanzaro documentation MAMMALITURCHI Temporary public installation wood structure + 431 lights A 10 meters illuminated sign placed under two trees on the most pop- ular beach in Porto Cesario (Puglia), saying PUNKABBESTIA. Porto Cesario - Italy 2007 Porto Cesario is a small community of 5000 inhabitants during winter season (that reaches picks of 100.000 in summer), due to it size, relations among citizen of Porto Cesario are very close. On the contrary, the “foreign” (“what comes from outside”) is often seen with a certain degree of suspect. With the installation I intended to comment on the seasonal fear of hippies (punkab- bestia) free camping on the southern cost of Italy and on the mystification of this phenomenon by local media. PUNKABBESTIA / from Wikipedia Punkabbestia is a slangy term used for identifying a type of vaga- bond and met-ropolitan homeless.Etymology The word seems to derive from the union of the words punk (subculture with which the punkabbestia have in common nu-merous nihilistic attitudes as the abuse of alcohol or other drugs, but not neces-sarily the musical references or the look) and beast (because of the stray dogs with which they are accompanied and of the displayed lack of care and personal hy-giene).According to others the word punkabbes-tia would have been coined in the years ‘80 from the Tuscan punks. Initially such term pointed out the punks that brought their ideological choice to the extreme, both politically and aesthetically, refusing in the whole in force society.Sociologi- cal description Punkabbestia is a term that has the ten-dency to be used for pointing out differ-ent types of social behaviours, also very distant between them: the term would treat therefore more an aesthetical pre-conception that a real category of people. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Visual Foxpro

RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT BHINDER IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/2/2003 33835 Sh.Bhagwati Lal Choubisa N.A.* 2 R/223/2007 47749 Sh.Laxman Giri Goswami L.T.M. 3 R/393/2018 82462 Sh.Manoj Kumar Regar N.A.* 4 R/3668/2018 85737 Kum.Kalavati Choubisa N.A.* 5 R/2130/2020 93493 Sh.Lokesh Kumar Regar N.A.* 6 R/59/2021 94456 Sh.Kailash Chandra Khariwal L.T.M. 7 R/3723/2021 98120 Sh.Devi Singh Charan N.A.* Total RAWF Members = 2 Total Terminated = 0 Total Defaulter = 0 N.A.* => Not Applied for Membership, L.T.M. => Life Time Member, Termi => Terminated Member RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT GOGUNDA IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/460/1975 6161 Sh.Purushottam Puri NIL + 1250 = 1250 1250 16250 2 R/337/1983 11657 Sh.Kanhiya Lal Soni 6250+2530+1250=10030 10125 25125 3 R/125/1994 18008 Sh.Yuvaraj Singh L.T.M. -

87 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

87 bus time schedule & line map 87 Kalupur Terminus - Chandkheda View In Website Mode The 87 bus line (Kalupur Terminus - Chandkheda) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chandkheda: 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM (2) Kalupur Terminus: 7:50 AM - 10:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 87 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 87 bus arriving. Direction: Chandkheda 87 bus Time Schedule 26 stops Chandkheda Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Monday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Maninagar Maninagar Railway Station, Ahmadābād Tuesday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Jawahar Chowk Wednesday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Bhairavnath Thursday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Friday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Sah Alam Darwaja Saturday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM S. T. Stand Kamnath Mahadev / Raipur Darwaja Sarangpur 87 bus Info Direction: Chandkheda Kalupur Stops: 26 Trip Duration: 47 min Naroda Road, Ahmadābād Line Summary: Maninagar, Jawahar Chowk, Prem Darwaja Bhairavnath, Sah Alam Darwaja, S. T. Stand, Kamnath Mahadev / Raipur Darwaja, Sarangpur, Kalupur, Prem Darwaja, Dariyapur Darwaja, Delhi Dariyapur Darwaja Darwaja, Income Tax O∆ce, Usmanpura, Vadaj Bus Terminuss, Subhash Bridge, Keshav Nagar, Delhi Darwaja Dharmanagar, Ram Nagar, Chintamani Society, Abu Koba Cross Road, Gujarat Stadium, Motera Gam, Income Tax O∆ce Government Engineering College, Santokba Hospital, Shivshakti Nagar, Chandkheda Usmanpura Vadaj Bus Terminuss Subhash Bridge Keshav Nagar Dharmanagar Ram Nagar Chintamani Society Abu Koba Cross Road Ram Bag Road, Ahmadābād Gujarat Stadium -

RAJASTHAN STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY, JAIPUR MEDIATION TRAINING PROGRAMME up to 31-5-2012 S.No

RAJASTHAN STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY, JAIPUR MEDIATION TRAINING PROGRAMME UP TO 31-5-2012 S.No. Divisional Head Date of holding the Concerned No. of No. Judicial officer Total No. of No. of No. of Name of trainers Remarks. Quarter Mediation training districts Advocates Trained Trained Referral mediators Judicial Judges. Advocates Offers as Mediator 01 Jaipur HQ 25 .4.2009 to -- 13Adv.+4 02 Dy. 18 02 --- Mr. Prasad Subbanna, 30.4.2009 Adv. Total Sec. RSLSA Advocate and 18 Mediator and co- ordinator, Bangalore. Mr. B.K. Mehta, Advcoate & mediator, Bangalore 02 Jodhpur HQ 31 Marth 2011 to 1st RHC Jodhpur 18 -- 18 -- 25 Mrs. Neena Krishna April,2011 and 9 to Bansal- Home Court 12 April, 2011 Delhi. Shri Arun Kumar Arya- Home Court – Delhi. 03 Jaipur Division 15.7.2011 to Jaipur Distt. 07 08 40+01 42 32 Mr. V.K. Bansal- Home 17.7.2011 Jaipur Metro 11+01 S.W. 14 123 Court,Delhi 22.7.2011 to Dausa 05 04 11 09310384709 24.7.2011 Sikar 04 04 13 Ms. Anju Bajaj 2nd round Jhunjhunu 06 04 12 Chandra- Home 06-01-2012 to 08-1- Alwar 07 08 55 Court,Delhi 2012 and 27-1-2012 09910384712 to 29-1-2012 2nd round 10-2-2012 to 12-2- Anju Bajaj chandana & 2012and 24 to 26-02- V.Khana , Shalinder 2012 JPR DISTT. kaur.(Jaipur Distt.) 11-5-2012 to 13-5- Ms. Neena Krishana 2012 and 25-5-2012 Bansal 09910384633 to 27-5-2012 Sh. Dharmesh Sharma 09910384689 04 Ajmer Division 05.08-2011 to Ajmer 10+01 S.W. -

Behrouz Biryani

Online Offer – Behrouz Biryani: • G 42, Shree Mahalaxmi Shops, Rudra Square, Bodakdev, Ahmedabad • 25, Rivera Arcade, Near Prahlad Nagar Garden, Prahlad Nagar, Ahmedabad • 2, IM Complex, Vastrapur Lake, Vastrapur, Ahmedabad • G/F 1, Animesh Complex, Panchavati Ellis Bridge, Near Chandra Colony, C G Road, Ahmedabad • 14, Ground Floor, Vitthal the Mall, Near Swagat Status, Chandkheda • C-19-20 Swagat Rainforest 2, Village Kudasan, Ta and District, Airport Gandhinagar Highway, Gandhinagar, Ahmedabad • 7th Cross Road, 8th Main, BTM Layout, Bangalore • Near Sony World Signal, Koramangala 6th Block, Bangalore • Kodichikkanahalli Main Road, Begur Hobli, Bommanahalli, Bangalore • Ground Floor, Actove Hotel, Kadubisanahalli, Marathahalli, Bangalore • Food Court, Sjr I-Park, Built In, Whitefield, Bangalore • Old Airport Road, Old Airport Road, Bangalore • Devatha Plaza, Residency Road, Bangalore • 123, Kamala Complex, AECS Layout, ITPL Main Road, Whitefield, Bangalore • 2318, Sector 1, Near NIFT College, HSR Layout, Bangalore • Kaggadaspura, CV Raman Nagar, Bangalore • Shop A-94 6/2, Opposite State Bank of India, 2nd Phase, J P Nagar, Bangalore • 101, Ground Floor, Manjunatha Complec, 22nd Main Road, 2nd Stage, Banashankari, Bangalore • Site No 8, New No 1, Channasandra, Property No 121, 2nd Main Road, Kr Puram Hobli, Kasturi Nagar, Bangalore • Shop 10-11, Electronic City Phase-1, 2nd Cross Road, Near Infosys Gate 1, Bangalore • 2283, 1st Main Road, Sahakar Nagar D Block, Bangalore • 3, 1st Floor, Apple City, Kadugodi Hoskote, Main Road, Seegehalli, Bangalore • Shop No. 837, BEML 3rd Stage, Halagevaderahalli, Rajarajeshwari Nagar, Bangalore • Dodaballapur Main Road, Puttenahalli, Yelahanka, Bangalore • Colony Skylineapartment, Canara Bank, Chandra Layout, Bangalore • Shop No. 90, First Floor, Sanjay Nagar Main Road, Geddalahalli, Bangalore • 6, First Floor, 9 Cross, 2nd Main, Binnamangala, 1st Stage, Indiranagar, Bangalore • Shop No. -

Monetary Aspects of Bahmani Copper Coinage in Light of the Akola Hoard

Monetary Aspects of Bahmani Copper Coinage in Light of the Akola Hoard Phillip B. Wagoner and Pankaj Tandon Draft: 9/24/16 **Please do not quote or disseminate without permission of the authors** The Bahmanis of the Deccan produced copper coinage from the very outset of the state’s founding in AH 748/1347 CE, but it was clearly secondary to the silver tankas upon which their monetary system was based. By the first several decades of the fifteenth century, however, as John Deyell has shown, the relative production values of silver and copper coinage had reversed, and there was an enormous expansion in copper output, both in terms of the numbers of coins produced and in terms of the range of their denominations (Fig.1).1 This phenomenon has attracted the attention of several scholars, but fundamental questions yet remain about the copper coinage and how it functioned within the Bahmani monetary system. Given the dearth of contemporary written documents shedding light on these matters, it is understandable that many would simply give up on trying to answer these questions. But to do so would be to ignore the physical, material evidence afforded in abundance by the coinage itself, including such aspects as its metrology and denominational structure, and most importantly, the indications of its usage patterns embodied within the composition and geographic distribution of individual coin hoards. Ultimately, we may wish to know why Bahmani copper coinage production should have undergone such a sudden expansion in the 1420s and 1430s, but in order to realize this goal, we must first address the physical nature of the coinage itself and what it can tell us about how it was used. -

Integrated Land Use and Transport Planning Ahmedabad City

29.09.2014 INTEGRATED LAND USE AND TRANSPORT PLANNING AHMEDABAD CITY By I.P.GAUTAM, VICE CHAIRMAN & MANAGING DIRECTOR AHMEDABAD METRO RAIL CO.(MEGA ) GANDHINAGAR , GUJARAT URBAN PROFILE OF GUJARAT • Gujarat : One of the Most Urbanized States in the Country. Accounts for 6% of the total geographical area of the Country Around 5% of the Country’s population of 1.21 billion. Total Population of Gujarat 60.4 million State Urban Population 25.7 million (42.58%) Gujarat Urban Population Gujarat Rural Population National Urban Population 31.16% 42.58% 57.42% State Urban Population 42.58% 0 1020304050 Source : Census 2011 ( Provisional Figures) Ahmedabad – Gandhinagar Region Ahmedabad 7th largest city in India Population 6.4 million 3 JANMARG Network Operational BRT Network Proposed BRT Network Built up Area River BRTS AHMEDABAD & LAND USE Chandkheda Sabarmati Rly. stn Naroda Ranip Ahmedabad village Sola RoB Airport. RTO Naroda GIDC NarodaNaroda AEC Gujarat University DuringGandhigram peak Rly. Odhav Bopal stn Kalupur Rly. Industrial estate hours Stn. Odhav Shivranjani Nehrunagar Soninicha During off peak ManinagarRl ali Geeta y. stn. hoursMandir Kankaria Anjali Danilimda Junction JashodanagarJn Narol Vatva Industrial Narol estate Metro rail alignment – First phase North South Corridor 15.4 km East West Corridor 20.5 Km 6 Intergrated MRT & BRTS Ahmedabad 7 Metro integration with AMTS & BRTS in 2018/2021 8 Special Provisions for Urban Transport System in the Development Plans of Ahmedabad & Gandhinagar 1. Proposed Metro Rail & BRTS corridors are integral part of Development Plan 2021. / Master Plan of Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA) and Gandhinagar Urban Development Authority (GUDA), 2. -

Ahmedabad Gandhinagar Metro - MEGA, Ahmedabad

Birla Vishvakarma Mahavidyalaya Engineering College, V. V. Nagar 388120 A Report on Industrial/Site Visit Ahmedabad Gandhinagar Metro - MEGA, Ahmedabad Construction of Helipad Building at V. S. Hospital, Ahmedabad Organized by: Structural Engineering Department Starting Date & Time: 05/1001/20167, 08:030 am Pick up point: BVM Engineering College, V. V. Nagar Venue & Place of Company: 1. Ahmedabad Gandhinagar Metro - MEGA, Ahmedabad 2. Construction of Helipad Building at V. S. Hospital, Ahmedabad Duration: 1 Day Faculty Members: • Prof. B. R. Dalwadi • Prof. V. A. Arekar Co-ordinated by: Prof. V. V. Agrawal Total Number of Students: 25 (Students of Elective: DESIGN OF PRESTRESSED CONCRETE STRUCTURES & BRIDGES) A technical tour for a day was organized for the students of civil engineering department by Structure engineering department of our college Birla Vishvakarma Mahavidyalaya under IEI. Students gathered at the college campus at around 8:30 am for registration and total 25 students registered themselves for the visit. We had 4 faculties from structure department along with us. Ahmedabad Gandhinagar Metro - MEGA First of all we went to the Ahmedabad Metro Rail Project site-phase 1 which was in the stretch of 6 km. The construction of the site was under J. Kumar pvt. ltd. The financing was done by state and central government. JICA of Japan has funded it with 4870 crores for the entire stretch of the Metro Link Express For Gandhinagar and Ahmedabad (MEGA) Company Ltd. On the casting yard we first met the planning engineer of the site Devam Patel who was the representative of J. kumar. He gave us the detailed information of the project regarding concrete mix, grade of concrete, design of segment, launching of girders, station details.