Helquist's and Snicket's All-Seeing Eyes: Panopticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bad Beginning by Lemony Snicket Book Discussion and Activities

The Bad Beginning By Lemony Snicket Book Discussion and Activities Discussion Questions: 1. At the beginning of the book, how did the author make you want to keep reading? 2. How do you picture the city where the Baudelaire children live? 3. Tell me what you think of Mr. Poe. 4. What is the first impression the Baudelaires have of Count Olaf? How often do you rely on the first impression you have of someone? How much effort do you put into making a good first impression when you meet someone new? 5. Count Olaf is obviously a villain. Think of other villains in other books that you have read and compare him to them. 6. Talk about the personalities of Violet, Klaus, and Sunny. To which character are you most similar? 7. Eyes are all around Count Olaf. What is the meaning of the eyes? 8. Lemony Snicket will often use a word like “standoffish” as an example and then add “a word here which means . .” Did this help you learn the meanings of new words? Do you think it is important to have a good vocabulary? Why? 9. Why does the author give the reader hope that things will go well for the children, for example with Justice Strauss, and then take away the hope? 10. How would the story be different if the orphans fought with each other rather than working together to solve their problems? Extension Activities: 1. Character suitcase - pick one of the characters from the story and pack a suitcase for that character to take on a trip. -

EBCS AR Titles

EBCS AR Titles QUIZNO TITLE 41025EN The 100th Day of School 35821EN 100th Day Worries 661EN The 18th EmerGency 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea 11592EN 2095 8001EN 50 Below Zero 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins 413EN The 89th Kitten 80599EN A-10 Thunderbolt II 16201EN A...B...Sea (Crabapples) 67750EN Abe Lincoln Goes to WashinGton 1837-1865 101EN Abel's Island 9751EN Abiyoyo 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't Roast Marshmallows 13551EN Abraham Lincoln 866EN Abraham Lincoln 118278EN Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War 17651EN The Absent Author 21662EN The Absent-Minded Toad 12573EN The Absolutely True Story...How I Visited Yellowstone... 17501EN Abuela 15175EN Abyssinian Cats (Checkerboard) 6001EN Ace: The Very Important PiG 35608EN The Acrobat and the AnGel 105906EN Across the Blue Pacific: A World War II Story 7201EN Across the Stream 1EN Adam of the Road 301EN Addie Across the Prairie 6101EN Addie Meets Max 13851EN Adios, Anna 135470EN Adrian Peterson 128373EN Adventure AccordinG to Humphrey 451EN The Adventures of Ali Baba Bernstein 20251EN The Adventures of Captain Underpants 138969EN The Adventures of Nanny PiGGins 401EN The Adventures of Ratman 64111EN The Adventures of Super Diaper Baby 71944EN AfGhanistan (Countries in the News) 71813EN Africa 70797EN Africa (The Atlas of the Seven Continents) 13552EN African-American Holidays EBCS AR Titles 13001EN African Buffalo (African Animals Discovery) 15401EN African Elephants (Early Bird Nature) 14651EN Afternoon on the Amazon 83309EN Air: A Resource Our World Depends -

![[Zm8ep.Ebook] a Series of Unfortunate Events #4: the Miserable Mill Pdf Free](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6347/zm8ep-ebook-a-series-of-unfortunate-events-4-the-miserable-mill-pdf-free-576347.webp)

[Zm8ep.Ebook] a Series of Unfortunate Events #4: the Miserable Mill Pdf Free

zm8ep [Read ebook] A Series of Unfortunate Events #4: The Miserable Mill Online [zm8ep.ebook] A Series of Unfortunate Events #4: The Miserable Mill Pdf Free Par Lemony Snicket audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #65016 dans eBooksPublié le: 2009-10-13Sorti le: 2009-10- 13Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 30.Mb Par Lemony Snicket : A Series of Unfortunate Events #4: The Miserable Mill before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised A Series of Unfortunate Events #4: The Miserable Mill: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Shirley, you must be joking.Par BernieOnce again, the Baudelaire orphans are transplanted in what will turn out to be a "Series of Unfortunate Events." Their newest home is the Lucky Smells Lumbermill dormitory.Here once again Lemony tells the meaning of many words (usually with words that need the meaning explained.) We are treated to the difference of literally and figurative among other such concepts.Naturally, they think everyone is Olaf. Moreover, of course they are correct. A mystery has to be solved and to do this Violet must learn Klaus's skills of reading apprehension. Then there are lives to be saved and Klaus must learn Violets' inventive skills. Sunny stays En garde.The Wide Window: Or, Disappearance! (A Series of Unfortunate Events, Book 3)0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Shirley, you must be joking?Par BernieOnce again the Baudelaire orphans are transplanted in what will turn out to be a "Series of Unfortunate Events." Their newest home is the Lucky Smells Lumbermill dormitory.Here once again Lemony tells the meaning of many words (usually with words that need the meaning explained.) We are treated to the difference of literally and figurative among other such concepts.Naturally they think everyone is Olaf. -

The YA Novel in the Digital Age by Amy Bright a Thesis

The YA Novel in the Digital Age by Amy Bright A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies University of Alberta © Amy Bright, 2016 Abstract Recent research by Neilsen reports that adult readers purchase 80% of all young adult novels sold, even though young adult literature is a category ostensibly targeted towards teenage readers (Gilmore). More than ever before, young adult (YA) literature is at the center of some of the most interesting literary conversations, as writers, readers, and publishers discuss its wide appeal in the twenty-first century. My dissertation joins this vibrant discussion by examining the ways in which YA literature has transformed to respond to changing social and technological contexts. Today, writing, reading, and marketing YA means engaging with technological advances, multiliteracies and multimodalities, and cultural and social perspectives. A critical examination of five YA texts – Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief, Libba Bray’s Beauty Queens, Daniel Handler’s Why We Broke Up, John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars, and Jaclyn Moriarty’s The Ghosts of Ashbury High – helps to shape understanding about the changes and the challenges facing this category of literature as it responds in a variety of ways to new contexts. In the first chapter, I explore the history of YA literature in order to trace the ways that this literary category has changed in response to new conditions to appeal to and serve a new generation of readers, readers with different experiences, concerns, and contexts over time. -

Count Olaf's Failures Seen in Lemony Snicket's a Series Of

PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI COUNT OLAF’S FAILURES SEEN IN LEMONY SNICKET’S A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS: THE BAD BEGINNING AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By NIKO NEKA PRASETYA Student Number: 084214099 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2013 i PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis COUNT OLAF’S FAILURES SEEN IN LEMONY SNICKET’S A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS: THE BAD BEGINNING By NIKO NEKA PRASETYA Student Number: 084214099 Approved by Dewi Widyastuti S. Pd., M. Hum. October 16, 2013. Advisor Ni Luh Putu Rosiandani S. S., M. Hum. October 16, 2013. Co-Advisor ii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis COUNT OLAF’S FAILURES SEEN IN LEMONY SNICKET’S A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS: THE BAD BEGINNING By NIKO NEKA PRASETYA Student Number: 084214099 Defended before the Board of Examiners on October 28, 2013 and Declared Acceptable BOARD OF EXAMINERS Name Signature Chairman : Dr. F.X. Siswadi, M. A ____________ Secretary : Sri Mulyani, Ph.D. Member 1. : Sri Mulyani, Ph.D. Member 2. : Dewi Widyastuti, S.Pd., M.Hum. Member 3 : Ni Luh Putu Rosiandani S. S., M. Hum. Yogyakarta, October 31, 2013 Faculty of Letters Sanata Dharma University Dean Dr. F.X. Siswadi, -

A Worldfor Children, a World Ofallusion: an Analysis Ofthe Allusions Within a Series Ofunfortunate Events

A Worldfor Children, A World ofAllusion: An Analysis ofthe Allusions within A Series ofUnfortunate Events An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Ashley Starling Thesis Advisor Dr. Joyce Huff Signed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2015 Expected Date of Graduation May 2015 l 2 Abstract Children's literature is often a genre that is considered to be too simple or too juvenile for serious scholarly consideration. This genre, typically associated with teaching children basic morals or cultural values, is one that adults do not often venture to read. This does not mean that all of children's literature does not contain elements that make them appropriate for both children and adult readers. In this thesis, I examine Daniel Handler's A Series ofUnfortunate Events and the way in which Handler utilizes allusions specifically in a way that mimics the very stage of childhood. Handler creates a series that is intended for a child audience but its clever use of the literary archive deems it also enjoyable by adult readers. 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Joyce Huff for advising me through this project. Her insight into various areas and aspects of literature became quite valuable for the completion of this project. Furthermore, her personal enjoyment of Handler' s series has helped to keep my interest in this project through the end. 4 A World for Children, A World of Allusion: An Analysis of the Allusions within A Series ofUnfortunate Events Introduction Daniel Handler's A Series ofUnfortunate Events is a series that includes concepts that are not typically found in all children's books--one of the most obvious of these being the prolific inclusion of allusions. -

The Slippery Slope a Series of Unfortunate Events Book 10 Pdf Book by Lemony Snicket

Download The Slippery Slope A Series of Unfortunate Events Book 10 pdf book by Lemony Snicket You're readind a review The Slippery Slope A Series of Unfortunate Events Book 10 ebook. To get able to download The Slippery Slope A Series of Unfortunate Events Book 10 you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this file on an database site. Book File Details: Original title: The Slippery Slope (A Series of Unfortunate Events, Book 10) Age Range: 8 - 12 years Grade Level: 5 - 6 Lexile Measure: 1150L Series: A Series of Unfortunate Events (Book 10) 352 pages Publisher: HarperCollins (September 23, 2003) Language: English ISBN-10: 0064410137 ISBN-13: 978-0064410137 Product Dimensions:5 x 1.2 x 7 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 13330 kB Description: NOW A NETFLIX ORIGINAL SERIESLike bad smells, uninvited weekend guests or very old eggs, there are some things that ought to be avoided.Snickets saga about the charming, intelligent, and grossly unlucky Baudelaire orphans continues to alarm its distressed and suspicious fans the world over. The tenth book in this outrageous publishing effort features... Review: After a lull with the previous few books, Lemony Snicket is back to his finest with this tenth installment! It is exciting to see the Baudelaire girls maturing and experience firsts. Helquists illustrations do a fine job of showing our three favorite orphans taller and stronger as they face frightening frenemies and fiascoes. -

The Slippery Slope

The Slippery Slope scholastic.com /teachers/lesson-plan/whos-character-discussion-guide-slippery-slope This is based on A Series of Unfortunate Events: The Slippery Slope by Lemony Snicket. About the Book Pack your snow picks, folks, because once again, youre in for the adventure of your lives in this action- packed tale of the Baudelaire children and their continuing conflict with the evil Count Olaf. The story opens as Violet and Klaus, the older Baudelaire orphans, are speeding uncontrollably in a caravan along a high mountain path, heading fast down Mortmain Mountain, about to topple into the swirling waters of Stricken Stream. But Violet-ever the clever inventor-quickly concocts a sticky substance that helps to slow down the moving caravan and save the two from a painful fate. Meanwhile, Sunny, the youngest Baudelaire sibling, is traveling uphill, kidnapped by Count Olaf and forced to share a car ride with the evil man, his girlfriend, Esmé, and other assorted characters. The story takes twists and turns until Violet and Klaus—suffering indignities from snow gnats to a casserole dish—rescue Sunny from Olaf's clutches. Once united, the three children find themselves in a toboggan on Stricken Stream, separated from their friend, Quigley. Will the orphans ever be reunited with Quigley? One can only hope. Set the Stage Get students ready to read by discussing the cover and reviewing what they know about the main characters, which they probably recall from reading other books in the series. The Baudelaire children often find themselves in dangerous situations. Read aloud the title and study the illustration. -

Kristen Wilson the Slippery Slope

SURF Conference Proceedings 2016 Author: Kristen Wilson Session 3A Faculty Advisor: Kathleen Moran The Slippery Slope: How American Children's Literature at the Turn of the Millennium Prepares Children for the Nature of Evil & Adulthood “If you are interested in stories with happy endings, you would be better off reading some other book” (The Bad Beginning 1), or so Lemony Snicket (Daniel Handler) introduces his child readers to the world of the Baudelaire orphans, a bleak and depressing reality populated by horrors as absurd as they are persistent. This is hardly the world of optimism and promise that American children are so often inducted into through children’s literature, but why does this series of children’s books strike such a different tone than the majority of its contemporaries, let alone the long tradition of buoyant didacticism and general idealism of American children’s literature that came before it? After all, The Series of Unfortunate Events—a thirteen book series Handler published under the penname of Lemony Snicket between 1999 and 2006—hardly exists in a vacuum. No cultural work does. What elements and anxieties of the new millennium allowed and inspired Handler to break with tradition and enjoy mainstream success in a market traditionally the domain of the singularly uplifting? Moreover, how does Handler explore these anxieties and how do they function in a societal context? In this paper, I would like to explore Handler’s treatment of three central anxieties of the millennium: loss of structure, grief, and morality in a fallen world. First: loss of structure. The most profound and arguably important tragedy of the series happens even before the first page of the first book when the Baudelaires lose their parents and all of their worldly possessions in a terrible fire that burns their mansion to the ground. -

1. What's in the Witch's Kitchen? (Early Years) 2. Where's Spot

1. What's in the Witch's Kitchen? (Early years) Author: Nick Sharratt ISBN: 9781406340075 Publisher: Walker Books Ltd Britain's most popular artist presents a brilliantly original format that very young children will delight in time and again. The witch has hidden a trick and a treat in her magical kitchen cupboards! 2. Where's Spot? (Early Years) Author: Eric Hill ISBN: 9780141343747 Publisher: Penguin Random House Children's UK In Spot's first adventure children can join in the search for the mischievous puppy by lifting the flaps on every page to see where he is hiding. The simple text and colourful pictures will engage a whole new generation of pre- readers as they lift the picture flaps in search of Spot. 3. Red Rockets and Rainbow Jelly? (Early Years) Author: Sue Heap ISBN: 9780141383385 Publisher: Penguin Random House Children's UK Sue and Nick are best friends who like lots of different things in lots of different colours. Here, they show us some of their favourite things from purple hair and all things blue to red cars and red dogs. The artwork is stunning with each artist contributing alternate pages in their own inimitable style. Read at Home English booklist 1 4. Fancy Dress Farmyard (Early Years) Author: Nick Sharratt ISBN: 9781407115917 Publisher: Scholastic There's a party at the farmyard, and it's going to be fancy dress. Children will love lifting the flaps to discover which animals are hiding behind the disguises. Pig has come as a pirate, Duck as a superhero and Sheep as a wizard. -

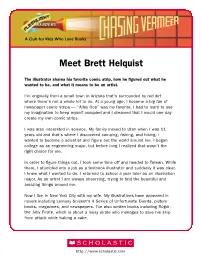

Meet Brett Helquist

A Club for Kids Who Love Books Meet Brett Helquist The illustrator shares his favorite comic strip, how he figured out what he wanted to be, and what it means to be an artist. I'm originally from a small town in Arizona that's surrounded by red dirt where there's not a whole lot to do. At a young age, I became a big fan of newspaper comic strips — “Alley Oop” was my favorite. I had to learn to use my imagination to keep myself occupied and I dreamed that I would one day create my own comic strips. I was also interested in science. My family moved to Utah when I was 11 years old and that's where I discovered camping, fishing, and hiking. I wanted to become a scientist and figure out the world around me. I began college as an engineering major, but before long I realized that wasn't the right choice for me. In order to figure things out, I took some time off and headed to Taiwan. While there, I stumbled into a job as a textbook illustrator and suddenly it was clear. I knew what I wanted to do. I returned to school a year later as an illustration major. As an artist I am always observing, trying to find the beautiful and amazing things around me. Now I live in New York City with my wife. My illustrations have appeared in novels including Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events, picture books, magazines, and newspapers. I've also written books including Roger, the Jolly Pirate, which is about a lousy pirate who manages to save his ship from attack while baking a cake. -

UNIVERSITY of VAASA Faculty of Philosophy English Studies Veera

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Osuva UNIVERSITY OF VAASA Faculty of Philosophy English Studies Veera Taipale Violet, Klaus and Sunny in Lemony Snicket’s The Series of Unfortunate Events Master’s Thesis Vaasa 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 3 1 INTRODUCTION 5 2 CHILDREN’S LITERATURE 13 2.1 Characteristics of Children’s Literature 14 2.2 Formula Stories 16 2.3 Literary Orphans 16 2.4 Fiction Series 20 3 CHARACTERS IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE 22 3.1 Collective Characters 22 3.2 Gender and Child Characters 24 4 VIOLET, KLAUS AND SUNNY AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO THE COLLECTIVE CHARACTER 32 4.1 Violet 32 4.2 Klaus 46 4.3 Sunny 55 5 CONCLUSIONS 61 6 WORKS CITED 63 3 UNIVERSITY OF VAASA Faculty of Philosophy Discipline: English Studies Author: Veera Taipale Master’s Thesis: Violet, Klaus and Sunny in Lemony Snicket’s The Series of Unfortunate Events. Degree: Master of Arts Date: 2016 Supervisor: Tiina Mäntymäki ABSTRACT Tässä tutkimuksessa tarkastellaan Lemony Snicketin The Series of Unfortunate Events - nimisen kirjasarjan kolmea päähenkilöä. Tutkimuksen päämääränä on selvittää, minkälaisia hahmoja Violet, Klaus ja Sunny Baudelaire ovat ja kuinka he muuttuvat sarjan edetessä. Lisäksi päähenkilöt muodostavat kollektiivisen hahmon, ja tutkimuksessa tarkastellaan sen vuoksi myös sitä, millä tavoin päähenkilöt täydentävät toisiaan ja kuinka kollektiivinen hahmo muuttuu sitä mukaa, kun erilliset hahmot kehittyvät. Tässä tutkimuksessa on hyödynnetty Maria Nikolajevan teoriaa selvitettäessä mitä lastenkirjallisuus on, mitä toistuvia teemoja siitä on löydettävissä, ja minkälaisia hahmoja lastenkirjallisuudessa usein esiintyy. Erityisesti Nikolajevan teoria kollektiivisista hahmoista luo pohjaa analyysille.