A Naval Aviator in the Cold War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

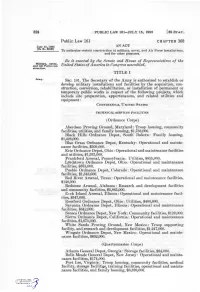

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

US Base Closings in Newfoundland, 1961–1994 Steven High

Document generated on 09/29/2021 3:10 a.m. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies Farewell Stars and Stripes US Base Closings in Newfoundland, 1961–1994 Steven High Volume 32, Number 1, Spring 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/nflds32_1art02 See table of contents Publisher(s) Faculty of Arts, Memorial University ISSN 1719-1726 (print) 1715-1430 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article High, S. (2017). Farewell Stars and Stripes: US Base Closings in Newfoundland, 1961–1994. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, 32(1), 42–85. All rights reserved © Memorial University, 2017 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Farewell Stars and Stripes: US Base Closings in Newfoundland, 1961–1994 Steven High Despite a chilly wind off of Placentia Bay, thousands of people gath- ered in Argentia to watch the controlled implosion of the 10-storey Combined Bachelor Quarters, known affectionately as the “Q,” on 6 November 1999. Cars lined up bumper to bumper for eight kilometres on the only road leading to the former US Navy base on Newfound- land’s Avalon Peninsula. In anticipation, the organizers had prepared a designated viewing area, a bandstand, a first aid station, and conces- sion stands where visitors could purchase their “Implosion ’99” t-shirts. -

UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER July 2013

OUR CREED: To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives in the pursuit of duties while serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments. Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of America and its constitution. UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER July 2013 1 Lost Boats 3 Picture of the Month 10 Members 11 Honorary Members 11 CO’s Stateroom 12 XO’S Stateroom 14 Meeting Attendees 15 Minutes 15 Old Business 15 New Business 16 Good of the Order 16 Base Contacts 17 Birthdays 17 Welcome 17 Binnacle List 17 Quote of the Month 17 Word of the Month 17 Member Profile of the Month 18 Traditions of the Naval Service 21 Dates in U.S. Naval History 23 Dates in U.S. Submarine History 28 Submarine Memorials 48 Monthly Calendar 53 Submarine Trivia 54 Advertising Partners 55 2 USS S-28 (SS-133) Lost on July 4, 1944 with the loss of 50 crew members. She was conducting Lost on: training exercises off Hawaii with the US Coast Guard Cutter Reliance. After S-28 dove for a practice torpedo approach, Reliance lost contact. No 7/4/1944 distress signal or explosion was heard. Two days later, an oil slick was found near where S-28. The exact cause of her loss remains a mystery. US Navy Official Photo BC Patch Class: SS S Commissioned: 12/13/1923 Launched: 9/20/1922 Builder: Fore River Shipbuilding Co Length: 219 , Beam: 22 #Officers: 4, #Enlisted: 34 Fate: Brief contact with S-28 was made and lost. -

Ladies and Gentlemen

reaching the limits of their search area, ENS Reid and his navigator, ENS Swan decided to push their search a little farther. When he spotted small specks in the distance, he promptly radioed Midway: “Sighted main body. Bearing 262 distance 700.” PBYs could carry a crew of eight or nine and were powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-1830-92 radial air-cooled engines at 1,200 horsepower each. The aircraft was 104 feet wide wing tip to wing tip and 63 feet 10 inches long from nose to tail. Catalinas were patrol planes that were used to spot enemy submarines, ships, and planes, escorted convoys, served as patrol bombers and occasionally made air and sea rescues. Many PBYs were manufactured in San Diego, but Reid’s aircraft was built in Canada. “Strawberry 5” was found in dilapidated condition at an airport in South Africa, but was lovingly restored over a period of six years. It was actually flown back to San Diego halfway across the planet – no small task for a 70-year old aircraft with a top speed of 120 miles per hour. The plane had to meet FAA regulations and was inspected by an FAA official before it could fly into US airspace. Crew of the Strawberry 5 – National Archives Cover Artwork for the Program NOTES FROM THE ARTIST Unlike the action in the Atlantic where German submarines routinely targeted merchant convoys, the Japanese never targeted shipping in the Pacific. The Cover Artwork for the Veterans' Biographies American convoy system in the Pacific was used primarily during invasions where hundreds of merchant marine ships shuttled men, food, guns, This PBY Catalina (VPB-44) was flown by ENS Jack Reid with his ammunition, and other supplies across the Pacific. -

Red Cliff Museum Enhancement Project a Collection O/Interviews, Research, Pictures and Stories

Red Cliff Museum Enhancement Project A collection o/Interviews, Research, Pictures and Stories Table of Contents 1.0 Background Information/Summaries 1.1 Red Clitf - American Radar Station 1951-1962 1.2 The American Connection of Red Cliff on our Town 2.0 Interview Reports and Consent Forms: 2.1 Lannis Huckabee 2.2 Jeremiah Pahukula 2.3 Norvell and Alice Simpson 2.4 Jay Stephens 2.5 Paul Winterson 3.0 Stories 3.1 All's Fair in Love and War 3.2 How I met my wife 3.3 My First Day at Red Cliff 3.4 On Duty? or On Air? 4.0 Red Cliff Questionnaires 4.1 Summary of respondents 4.2 Original copies of completed questionnaires 5.0 Pictures 5. I Present day (2007) Red CI i ff 6.0 Miscellaneous/Appendix 6.1 Picture of a USAF Squadron Emblem 6.2 Open House Poster 6.3 Emails 7.0 Sources of Research 7.1 "US Military Locations" 7.2 "St. John's (Red Clift), NF" 7.3 "Pinetreeline Miscellaneous" 7.4 "Memories of Red Clift" 7.5 "Life Goes On" Red Cliff American Radar Station 1951-1962 Construction of the American Air Force radar station at Red Cliff began in 1951. The station became operational in 1954. The facility was one of a series of AAF radar stations called the Pine Tree Line. The Pine Tree Line included radar stations across North America and as far as Greenland, and its purpose was to be a defense system against enemy aircraft during the Cold War. -

House' of Representatives

6132 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE Ap1"il 16 jobs one at a t~e. This is so for these send the restricted bill without delay to sented to the ·President of tlie United reasons: the Hguse, whose concurrence in the States the following-enrolled bills: First. Malpractices in the internal af action of the Senate would make it rea S. 144. An act to modify Reorganization fairs of unionS and problems arising out sonably certain that union treasuries Plan No. II of 1939 and Reorganization Plan of the external relations of industry and will not be pillaged with impunity by No. 2 of 1953; and · labor are quite dissimilar in nature, and their custodians, that unrepentant con S. 1096. An act to authorize appropriations require quite different legislative treat victed felons and racketeers will not be to the National Aeronautics and Space Ad ment. To combine the· consideration of given dominion over honest and law ministration for salari-es and expenses, re such diverse matters is not conducive to search and development, construction and abiding union members, that dictatorial equipment, and for other purposes, sound legislation because it tends to con union officers will not be allowed to rob fuse issues and distract legislators. union members of their basic rights by Second. The passage of needed legis-. abuse of the trustee process, that cor REC~SS lation to outlaw malpractices in the in.; rupt union officers will not be permitted The PRESIDING OFFICER. What is ternal affairs of unions ought not to oe to connive with management to betray· put in jeopardy by saddling such legisla the union members they represent, and the wish of the Senate? tion with unrelated controversies be that union members will possess the Mr. -

Comparative Connections

Pacific Forum CSIS Comparative Connections A Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations edited by Carl Baker Brad Glosserman May – August 2014 Vol. 16, No.2 September 2014 http://csis.org/program/comparative-connections Pacific Forum CSIS Based in Honolulu, Hawaii, the Pacific Forum CSIS operates as the autonomous Asia- Pacific arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1975, the thrust of the Forum’s work is to help develop cooperative policies in the Asia- Pacific region through debate and analyses undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate arenas. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic/business, and oceans policy issues. It collaborates with a network of more than 30 research institutes around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating its projects’ findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and publics throughout the region. An international Board of Governors guides the Pacific Forum’s work. The Forum is funded by grants from foundations, corporations, individuals, and governments, the latter providing a small percentage of the forum’s annual budget. The Forum’s studies are objective and nonpartisan and it does not engage in classified or proprietary work. Comparative Connections A Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations Edited by Carl Baker and Brad Glosserman Volume 16, Number 2 May – August 2014 Honolulu, Hawaii September 2014 Comparative Connections A Triannual Electronic Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations Bilateral relationships in East Asia have long been important to regional peace and stability, but in the post-Cold War environment, these relationships have taken on a new strategic rationale as countries pursue multiple ties, beyond those with the US, to realize complex political, economic, and security interests. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES Loan Act of 1933, As Amended; Making Appropriations for the Depart S

1955 .CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE 9249 ment of the Senate to the bill CH. R. ministering oaths and taking acknowledg Keller in ·behalf of physically handicapped 4904) to extend the Renegotiation Act ments by offi.cials of Federal penal and cor persons throughout ·the world. of 1951for2 years, and requesting a con rectional institutions; and H. R. 4954. An act to amend the Clayton The message also announced that the ference with the Senate on the disagree Act by granting a right of action to the Senate agrees to the amendments of the ing votes·of the two Houses thereon. United States to recover damages under the House to a joint resolution of the Sen Mr. BYRD. I move that the Senate antitrust laws, establishing a uniform ate of the following title: insist upon its amendment, agree to the statute of limitati9ns, and for other purposes. request of the House for a conference, S. J. Res. 67. Joint resolution to authorize The message also announced that the the Secretary of Commerce to sell certain and ~hat the Chair appoint the conferees Senate had passed bills and a concur vessels to citizens of the Republic of the on the part of the Senate. Philippines; to provide for the rehabilita The motion was agreed to; and the rent resolution of the following titles, in tion of the interisland commerce of the Acting President pro tempore appointed which the concurrence of the House is Philippines, and for other purposes. Mr. BYRD, Mr. GEORGE, Mr. KERR, Mr. requested: The message also announced that th~ MILLIKIN, and Mr. -

National Defense

National Defense of 32 code PARTS 700 TO 799 Revised as of July 1, 1999 CONTAINING A CODIFICATION OF DOCUMENTS OF GENERAL APPLICABILITY AND FUTURE EFFECT AS OF JULY 1, 1999 regulations With Ancillaries Published by the Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration as a Special Edition of the Federal Register federal VerDate 18<JUN>99 04:37 Jul 24, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8091 Sfmt 8091 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX 183121f PsN: 183121F 1 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1999 For sale by U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402±9328 VerDate 18<JUN>99 04:37 Jul 24, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 8092 Sfmt 8092 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX 183121f PsN: 183121F ?ii Table of Contents Page Explanation ................................................................................................ v Title 32: Subtitle AÐDepartment of Defense (Continued): Chapter VIÐDepartment of the Navy ............................................. 5 Finding Aids: Table of CFR Titles and Chapters ....................................................... 533 Alphabetical List of Agencies Appearing in the CFR ......................... 551 List of CFR Sections Affected ............................................................. 561 iii VerDate 18<JUN>99 00:01 Aug 13, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 8092 Sfmt 8092 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX pfrm04 PsN: 183121F Cite this Code: CFR To cite the regulations in this volume use title, part and section num- ber. Thus, 32 CFR 700.101 refers to title 32, part 700, section 101. iv VerDate 18<JUN>99 04:37 Jul 24, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 8092 Sfmt 8092 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX 183121f PsN: 183121F Explanation The Code of Federal Regulations is a codification of the general and permanent rules published in the Federal Register by the Executive departments and agen- cies of the Federal Government. -

Annual Naval Weather Service Association Reunion 10 – 14 September, 2008 Waukesha, Wi

(847) 438-4716 [email protected] Chaplain: CWO4 Bill Bowers, USN RET (352) 750-2970 [email protected] Finance: CAPT Bob Titus, USN RET (Chair) (775) 345-1949 [email protected] CAPT Dave Sokol, USN RET CAPT Chuck Steinbruck, USN RET Historian: CDR Don Cruse, USN RET (703) 524-9067 [email protected] Scholarship: AGCM Pat O’Brien, USN RET (Chair) (850) 968-0552 [email protected] xAG3 Charles E Moffett III, USN REL (609) 492-2883 [email protected] LCDR Mike Gilroy, USN RET (425) 418-8164 [email protected] Nominating: AGCM Moon Mullen, USN RET (805) 496-1348 [email protected] Parliamentary: AGCM Moon Mullen, USN RET (805) 496-1348 [email protected] Master-At-Arms: AGC Dan Hewins, USN RET COVER INFORMATION. This cover was inspired by an email between Frank Baillie and Frenchy Corbeille. From Frank Baillie: I was a young AG1 aboard USS Eldorado which arrived in Yokosuka in late 1952 with Phib Gru 3embarked. We tied up at a finger pier adjacent to the carrier pier. On an earlier Yokosuka port visit in USS Estes (1951) a carrier had arrived in port & used the Association Officers: "Pinwheel" maneuver to dock. The roar of all those President: AGCM Pat O’Brien, USN RET engines was deafening. 515 Ashley Rd., Cantonment FL 32533-0552 (850) 968-0552 [email protected] The Bridges at Toko-Ri - the rest of the story! 1st Vice President: CWO4 Bill Bowers, USN RET CAPT Paul N. Gray, USN, Ret, USNA '41, 5416 Grove Manor, Lady Lake FL32159-3533 former CO of VF-54 352 750-2970 [email protected] Forward by Carl Schneider 2nd Vice President: LCDR Earl Kerr, USN RET Having flown 100 combat missions during the brutally cold 386 Deception Rd., Anacortes WA 98221-9740 winter of 1950-51 in Korea on the same type of sorties as 360 293-5835 [email protected] those described---I can readily understand the situation. -

PUBLIC LAW 765-SEPT. 1, 1954 1119 Public Law 765 CHAPTER

68 STAT.] PUBLIC LAW 765-SEPT. 1, 1954 1119 Public Law 765 CHAPTER 1210 AN ACT September 1, 19!>4 To provide for family quarters for personnel of the military departments of the [H. R. 9924] Department of Defense and their dependents, and for other purposes. Be it enacted l)y the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assemhled, Forc- ^"ye *famil ^avyy houis, Ai-r ing. TITLE I SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized further to develop ^'"^' military installations and facilities by providing family housing for personnel of the military departments and their dependents by the construction or installation of public works, Avhich include site prepara tion, appurtenances, utilities, equipment and the acquisition of land, as follows: CONTINENTAL UNITED STA'i'ES (Third Army Area) Fort Campbell, Kentucky: Three hundred units of family housing, $4,093,000. (Fourth Army Area) Fort Bliss, Texas: Two hundred and fiftv units of family housing, $3,213,000. Fort Hood, Texas: Six hundred units of family housing, $8,099,000. (Fifth Army Area) Camp Carson, Colorado: One thousand units of family housing, $13,427,000. Camp Crowder, Missouri: Seventy units of family housing, $952,000. (Sixth Army Area) Fort Lewis, Washington: Eight hundred units of family housing, $10,686,000. Camp Cooke (United States Disciplinary Barracks), California: Fifty units of family housing, $663,000. Yuma Test Station, Arizona: Twenty units of family housing, $267,000. (Quartermaster Corps) Belle Mead General Depot, New Jersey: Ten units of family hous ing, $158,000. (Chemical Corps) Dugway Proving Ground, Utah: Thirty units of family housing, $486,000. -

An Analysis of International Air Freight Forwarding Support for the United States Navy

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1985 An analysis of international air freight forwarding support for the United States Navy. Lake, Robert H. Jr. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/27966 DUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA 93943 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS AN ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL AIR FREIGHT FORWARDING SUPPORT FOR THE UNITED STATES NAVY by Robert H. Lake, Jr. June 19 8 5. Thesis Advisor D.C. Soger Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. 1222865 UNCLASSIFIED SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE (Whan Data Entered) REPORT DOCUMENTATION READ INSTRUCTIONS PAGE BEFORE 1. REPORT NUMBER COMPLETING FORM 2. GOVT ACCESSION 3 NO - RECIPIENTS CATALOG NUMBER" « TITLE (and Subtitle) TYPE 5. OF REPORT 4 PERIOD COVERED An Analysis of International Air Freight Master's Thesis Forwarding Support For the United States Navy June 1985 6. PERFORMING ORG. REPORT NUMBER 7- AUTHORCsj 8 CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBERC.j" Robert H. Lake, Jr. 9- PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS ,0 - " ' "OGRAM ELEMENT, AREA PROJECT TASK Naval Postgraduate School & WORK UNIT NUMBERS Monterey, California 93943-5100 H. CONTROLLING OFFICE NAME AND ADDRESS 12. REPORT DATE Naval Postgraduate School June Monterey, 1985 California 93943-5100 '3. NUMBER OF PAGES 104 1«. MONITORING AGENCY NAME & ADDRESSf// different from Controlling Office) 15. SECURITY CLASS, (of tht, report) Unclassified ' 5 *' DECLASSIFICATION/ DOWNGRADING o\->H fc. !_J U Lb E. 16. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT (of this Report) Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. 17. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT (of the abstract entered In Block 20, II different from Report) 18. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 19. KEY WORDS (Continue on reverse side If necessary and Identity by block numb.