Introduction to LATEX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latex on Windows

LaTeX on Windows Installing MikTeX and using TeXworks, as described on the main LaTeX page, is enough to get you started using LaTeX on Windows. This page provides further information for experienced users. Tips for using TeXworks Forward and Inverse Search If you are working on a long document, forward and inverse searching make editing much easier. • Forward search means jumping from a point in your LaTeX source file to the corresponding line in the pdf output file. • Inverse search means jumping from a line in the pdf file back to the corresponding point in the source file. In TeXworks, forward and inverse search are easy. To do a forward search, right-click on text in the source window and choose the option "Jump to PDF". Similarly, to do an inverse search, right-click in the output window and choose "Jump to Source". Other Front End Programs Among front ends, TeXworks has several advantages, principally, it is bundled with MikTeX and it works without any configuration. However, you may want to try other front end programs. The most common ones are listed below. • Texmaker. Installation notes: 1. After you have installed Texmaker, go to the QuickBuild section of the Configuration menu and choose pdflatex+pdfview. 2. Before you use spell-check in Texmaker, you may need to install a dictionary; see section 1.3 of the Texmaker user manual. • Winshell. Installation notes: 1. Install Winshell after installing MiKTeX. 2. When running the Winshell Setup program, choose the pdflatex-optimized toolbar. 3. Winshell uses an external pdf viewer to display output files. -

Installation Guide

Introduction to LATEX Workshop: Installation Guide This is a brief guide describing various options for installing a LATEX compiler and editor on your laptop or other computational device. The major software providers all provide automatic installers so in most cases it is as simple as navigating to the proper website and double clicking on an application. 1 Installing LATEX on your computer 1.1 Installing LATEX on Mac The standard compiler for Mac computers is called MacTEXwhich can be downloaded and installed from: http://tug.org/mactex/. The editor TEXMaker can be downloaded and installed from: www.xm1math.net/texmaker. 1.2 Installing LATEX on Windows The standard compiler for Windows computers is called MikTEXwhich can be downloaded and installed from: http://miktex.org/. The editor TEXMaker can be downloaded and installed from: www.xm1math.net/texmaker. 1.3 Installing LATEX on Linux Many contemporary Unix distributions are already packaged with a LATEXcompiler and editor. If you are using Ubuntu or Debian then you can install directly from the terminal by entering: sudo apt-get install texlive-full followed by sudo apt-get install texmaker. On RedHat or CentOS you can use sudo yum install tetex to obtain the compiler. In- stalling TEXmaker is a little more complicated but any text editor will work as well. 2 Tablets and Mobile Devices Most of the online editors have app versions that can be used from your phone or tablet. If you want to compile documents on these devices without an internet connection there are a few options. There are two popular ios apps: TeXPad and TeXWriter. -

Here Comes Number Two

LATEX Documents ALATEX source file is an ordinary text file with interspersed typography markup. It may be created with any text editor (Notepad, Textedit, A gedit, emacs, vim) or with a dedicated LATEX editor with syntax LTEX highlighting (Texstudio, Texmaker). This text file will then be processed by a T X engine: Leif Andersson E latex, pdflatex, lualatex, xelatex The result is a .pdf file, which may be printed or read on screen. The Environment A Short Document The most fundamental LATEX component is the Environment. Inside an environment the text gets a special layout and/or special commands are defined. \documentclass{article} \usepackage{fourier} This is a paragraph with some This is a paragraph with some \usepackage[swedish]{babel} surrounding text. \begin{document} surrounding text. \begin{itemize} H¨ar kommer texten till mitt banbrytande dokument. \item This is the first point. This is the first point. \end{document} \item And here comes number two. • And here comes number two. \begin{enumerate} • The part between \documentclass and \begin{document} is \item Multiple levels are possible 1. Multiple levels are possible called the preamble, and may contain definitions special to this \item They get automatically 2. They get automatically document. In particular it may call on packages with the indented and enumerated. indented and enumerated. \end{enumerate} \usepackage command. \item The last point The last point • There are also style options \end{itemize} We also have some text after the \documentclass[a4paper,12pt]{article} We also have some text after different items. the different items. Documentclasses Special Characters To get Write Used for A Standard LTEX: $ \$ Start and end of math article report book letter memoir beamer % \% Comment to end of line Journals and conferences often have their own classes. -

Texworks: Lowering the Barrier to Entry

TEXworks: Lowering the barrier to entry Jonathan Kew 21 Ireton Court Thame OX9 3EB England [email protected] 1 Introduction The standard TEXworks workflow will also be PDF-centric, using pdfT X and X T X as typeset- One of the most successful TEX interfaces in recent E E E years has been Dick Koch's award-winning TeXShop ting engines and generating PDF documents as the on Mac OS X. I believe a large part of its success has default formatted output. Although it will still be been due to its relative simplicity, which has invited possible to configure a processing path based on new users to begin working with the system with- DVI, newcomers to the TEX world need not be con- out baffling them with options or cluttering their cerned with DVI at all, but can generally treat TEX screen with controls and buttons they don't under- as a system that goes directly from marked-up text stand. Experienced users may prefer environments files to ready-to-use PDF documents. T Xworks includes an integrated PDF viewer, such as iTEXMac, AUCTEX (or on other platforms, E based on the Poppler library, so there is no need WinEDT, Kile, TEXmaker, or many others), with more advanced editing features and project man- to switch to an external program such as Acrobat, agement, but the simplicity of the TeXShop model xpdf, etc., to view the typeset output. The inte- has much to recommend it for the new or occasional grated viewer also allows it to support source $ user. -

Setting up Your Working Environment

Setting Up your Working Environment By Christof Lutteroth This document gives some advice on how to get a working environment set up for an academic project in Computer Science. It outlines the various tools that make research in a group a little bit easier. If you have any questions, please discuss them with your supervisor. Collecting Citations using BibTeX BibTeX is the standard citation subsystem for LaTeX. It allows you to collect citations of various document types, such as conference papers, journal articles, books and technical reports. When using Google Scholar, you need to go to “Scholar Preferences” from the main page (scholar.google.com) and adjust the settings to make Google show links to BibTeX entries for each citation. The BibTex entries can be copied directly into your .bib file. If you are working from home and would like to access PDFs of publications through the university library, you can use the following Google Scholar proxy server: http://scholar.google.com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz Writing your Thesis using LaTeX The LaTeX typesetting system is a text-based compiler that reads a document description language and creates relatively nice looking documents such as PDFs. Although not always easy to use, it will help you to produce a thesis without having to worry too much about formatting issues. If you are working on Windows, make sure your computer has the MikTeX distribution installed (www.miktex.org). MikTeX is an implementation of LaTeX specifically for Windows. The “basic MikTeX system” should be enough. There are also LaTeX distributions for other operating systems. -

1 R Installation Instructions 2 LATEX Installation Instructions

1 R Installation Instructions 1. Download R from http://cran.r-project.org/mirrors.html.1 2. Once you've picked a mirror download R for your operating system. 3. When it's done downloading, install R. 4. (Optional) Download and install the most recent version of RStudio Desktop from http://www. rstudio.com/products/rstudio/download/.2 • Make sure you install R before RStudio. Not doing so could potentially cause issues. 2 LATEX Installation Instructions LaTeX is a powerful document preparation system. It allows you to output high-quality and customizable pdf documents. LATEX is a document markup language, meaning that it consists of syntax that specifies to the program how the document is to be formatted - that is, typesetting instructions. More common examples of markup languages are HTML and XML. Markup embedded in a LATEX document conveys formatting and processing specifications to the TEX engine. It then allows you to output fancy PDFs like this one (and just about everything else used in the Prefresher) To begin using LATEX you need to things: • LATEX front end or text editor to write a .tex file • LATEX compiler that processes the TEX code you've written and outputs the document you want Windows users: • Compiler: MiKTeX • Some editors: Texmaker , TeXnic Center , LyX. 3 Mac users: • Compiler: MacTeX • Some editors: TeXShop , Aquamacs , Texmaker , TextWrangler , Latexian 1It doesn't really matter which mirror you use. 2RStudio is, in my opinion, the best IDE (integrated development environment) for R. It allows you to simultaneously see your R Console, multiple scripts of code, all the objects in your workspace, your working directory, plots, installed packages, and help files. -

Fileweaver: Flexible File Management with Automatic Dependency Tracking Julien Gori Han L

FileWeaver: Flexible File Management with Automatic Dependency Tracking Julien Gori Han L. Han Michel Beaudouin-Lafon Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, Inria, Laboratoire de Recherche en Informatique F-91400 Orsay, France {jgori, han.han, mbl}@lri.fr ABSTRACT Specialized tools typically load and save information in pro- Knowledge management and sharing involves a variety of spe- prietary and/or binary data formats, such as Matlab1 .mat cialized but isolated software tools, tied together by the files files or SPSS2 .sav files. Knowledge workers have to rely on that these tools use and produce. We interviewed 23 scientists standardized exchange file formats and file format converters and found that they all had difficulties using the file system to communicate information from one application to the other, to keep track of, re-find and maintain consistency among re- leading to a multiplication of files. lated but distributed information. We introduce FileWeaver, a system that automatically detects dependencies among files Moreover, as exemplified by Guo’s “typical” workflow of a without explicit user action, tracks their history, and lets users data scientist [8, Fig. 2.1], knowledge workers’ practices often interact directly with the graphs representing these dependen- consist of several iterations of exploratory, production and cies and version history. Changes to a file can trigger recipes, dissemination phases, in which workers create copies of files either automatically or under user control, to keep the file con- to save their work, file revisions, e.g. to revise the logic of sistent with its dependants. Users can merge variants of a file, their code, and file variants, e.g. -

Tlaunch: a Launcher for a TEX Live System

TLaunch: a launcher for a TEX Live system Siep Kroonenberg June 29, 2017 This manual is for tlaunch, the TEX Live Launcher, version 0.5.3. Copyright © 2017 Siep Kroonenberg. Copying and distribution of this file, with or without modification, are permitted in any medium without royalty provided the copyright notice and this notice are preserved. This file is offered as-is, without any warranty. Contents 1 The launcher5 1.1 Introduction............................5 1.1.1 Localization........................6 1.2 Modes...............................6 1.2.1 Normal mode.......................6 1.2.2 Initializing.........................6 1.2.3 Forgetting.........................6 1.3 Using scripts............................7 1.4 The ini file.............................7 1.4.1 Location..........................7 1.4.2 Encoding..........................7 1.4.3 Syntax...........................7 1.4.4 The Strings section....................9 1.4.5 Sections for filetype associations (FTAs)........9 1.4.6 Sections for utility scripts................ 10 1.4.7 The built-in functions.................. 10 1.4.8 Menus and buttons.................... 11 1.4.9 The General section.................... 12 1.5 Editor choice............................ 12 1.6 Launcher-based installations................... 13 1.6.1 The tlaunchmode script................. 14 1.6.2 TEX Live Manager..................... 14 2 The launcher at the RUG 15 2.1 Historical.............................. 15 2.2 RES desktops........................... 16 2.3 Components of the rug TEX installation............ 16 2.4 Directory organization...................... 17 2.5 Fixes for add-ons......................... 17 2.5.1 TeXnicCenter....................... 17 2.5.2 TeXstudio......................... 18 2.5.3 SumatraPDF........................ 18 2.5.4 LyX............................. 18 3 CONTENTS 4 2.6 Moving the XeTEX font cache................. -

The Gsemthesis Class∗

The gsemthesis class∗ Emmanuel Rousseaux [email protected] February 9, 2015 Abstract This article introduces the gsemthesis class for LATEX. The gsemthesis class is a PhD thesis template for the Geneva School of Economics and Management (GSEM), University of Geneva, Switzerland. The class provides utilities to easily set up the cover page, the front matter pages, the pages headers, etc. with respect to the official guidelines of the GSEM Faculty for writing PhD dissertations. This class is released under the LaTeX Project Public License version 1.3c. ∗This document corresponds to gsemthesis v0.9.4, dated 2015/02/09. 1 Contents 1 Introduction3 2 Usage 3 2.1 Requirements..................................3 2.2 Getting started.................................3 2.3 Configuring your editor to store files in UTF-8...............4 2.4 Writing the dissertation in French......................4 2.5 Configuring and printing the cover page...................4 2.6 Configuring and printing the front matter pages...............4 2.7 Introduction and conclusion..........................5 2.8 Bibliography..................................5 2.8.1 Configure TeXstudio to run biber...................5 2.8.2 Configure Texmaker to run biber...................5 2.8.3 Configure Rstudio/knitr to run biber.................5 2.8.4 Basic commands............................6 2.8.5 Using you own bibliography management configuration......6 2.9 Draft mode...................................6 2.10 Miscellaneous..................................6 3 Minimal working example7 4 Implementation8 4.1 Document properties..............................8 4.2 Colors......................................8 4.3 Graphics.....................................8 4.4 Link management................................9 4.5 Maths......................................9 4.6 Page headers management...........................9 4.7 Bibliography management........................... 10 4.8 Cover page.................................. -

A Brief Introduction to Latex.Pdf

ME 601A, 2016-17, SEM II IIT Kanpur What are TeX and LaTeX? • LaTeX is a typesetting systems suitable for producing scientific and mathematical documents — LaTeX enables authors to typeset and print their work at the highest typographical quality. — LaTeX is pronounced “Lay-te ch”. — LaTeX uses TeX formatter as its typesetting engine. • TeX is a program written by Donald Kunth for typesetting text and mathematical formulas Why LaTeX ? • Easy to use, especially for typing mathematical formulas • Portability (Windows, Unix, Mac) • Stability and interchangeability Why LaTeX ? contd... • High quality Most journals /conferences have their LaTeX styles One will be forced to use it, since everyone else around is using it. Why LaTeX ? contd... Documentation and forums A universal acceptance among researchers Error finding and troubleshooting are not difficult ∞ J[x(⋅),u(⋅)] = ∫ F (x(t),u(t),t)dt t0 References for LaTeX — The not so short introduction to LaTeX2e http://tobi.oetiker.ch/lshort/lshort.pdf — Comprehensive TeX archive network http://www.ctan.org/ — Beginning LaTeX http://www.cs.cornell.edu/Info/Misc/LaTeX-Tutorial/LaTeX- Home.html — Google Leslie Lamport H. Kopka Process to Create a Document Using LaTeX TeX input file Your source LaTeX file.tex document Run LaTeX program DVI file Device independent file.dvi output Run Device Driver Unix Commands Output file > latex file.tex runs latex file.ps or file.pdf > xdiv file.dvi previewer > dvips file.dvi creates .ps > pdflatex file.tex creates .pdf directly How to Setup LaTeX for Windows • Download and install MikTeX LaTeX package http://www.miktex.org/ • Install Ghostscript and Gsview http://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~ghost/ PS device driver … • Install Acrobat Reader • Install Editor — WinEdt For MAC Users http://www.winedt.com/ TeXShop — TexnicCenter iTexMac http://www.texniccenter.org/ Texmaker — Emacs, vi, etc. -

More Latex and Julia and How to Use It to Prepare a Homework

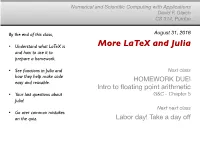

Numerical and Scientific Computing with Applications David F. Gleich CS 314, Purdue By the end of this class, August 31, 2016 • Understand what LaTeX is More LaTeX and Julia and how to use it to prepare a homework. • See functions in Julia and Next class how they help make code HOMEWORK DUE! easy and reusable. Intro to floating point arithmetic • Your last questions about G&C - Chapter 5 Julia! Next next class • Go over common mistakes on the quiz. Labor day! Take a day off Logistics 1. Final exam We will have the final EARLY (December 2) based on the results of the poll which overwhelmingly picked this option. Course Survey Matlab only 33 Numpy/Scipy only 5 Both 16 Latex 9 Taylor series 23 Topics Monte Carlo, ODEs, Matrices Stuff Julia & Mandelbrot sets! Quiz Results … at end of class ... LaTeX • A document typesetting system designed for beautiful mathematical documents. • TeX was designed by Donald Knuth • LaTeX was designed by Leslie Lamport • Both won Turing awards - Nobel prize of CS • You need to “compile” your documents. pdflatex myfile.tex # produces myfile.pdf Recommended packages + editors Windows • MiKTex and TexStudio Mac • MacTex and TexStudio or TexMaker Linux • TeXLive (or apt-get / yum package) + Kile or TexStudio Online • Overleaf • Juliabox Notebooks Making a simple document \documentclass{article} \usepackage[margin=1in]{geometry} \title{My document} \author{David and Collaborators} \begin{document} \maketitle \section{Problem 1} \section*{Solution} \section{Problem 1} \section*{Solution} \end{document} demo Editing a homework demo Back to Julia! . -

Latex in Twenty Four Hours

Plan Introduction Fonts Format Listing Tabbing Table Figure Equation Bibliography Article Thesis Slide A Short Presentation on Dilip Datta Department of Mechanical Engineering, Tezpur University, Assam, India E-mail: [email protected] / datta [email protected] URL: www.tezu.ernet.in/dmech/people/ddatta.htm Dilip Datta A Short Presentation on LATEX in 24 Hours (1/76) Plan Introduction Fonts Format Listing Tabbing Table Figure Equation Bibliography Article Thesis Slide Presentation plan • Introduction to LATEX Dilip Datta A Short Presentation on LATEX in 24 Hours (2/76) Plan Introduction Fonts Format Listing Tabbing Table Figure Equation Bibliography Article Thesis Slide Presentation plan • Introduction to LATEX • Fonts selection Dilip Datta A Short Presentation on LATEX in 24 Hours (2/76) Plan Introduction Fonts Format Listing Tabbing Table Figure Equation Bibliography Article Thesis Slide Presentation plan • Introduction to LATEX • Fonts selection • Texts formatting Dilip Datta A Short Presentation on LATEX in 24 Hours (2/76) Plan Introduction Fonts Format Listing Tabbing Table Figure Equation Bibliography Article Thesis Slide Presentation plan • Introduction to LATEX • Fonts selection • Texts formatting • Listing items Dilip Datta A Short Presentation on LATEX in 24 Hours (2/76) Plan Introduction Fonts Format Listing Tabbing Table Figure Equation Bibliography Article Thesis Slide Presentation plan • Introduction to LATEX • Fonts selection • Texts formatting • Listing items • Tabbing items Dilip Datta A Short Presentation on LATEX