A Case for Building Conservation in a Modern Society: Bear Down Gym

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100709 WBB MG Text.Id2

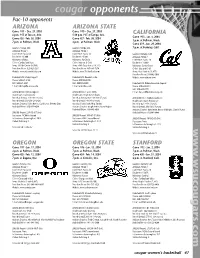

cougar opponents Pac-10 opponents ARIZONA ARIZONA STATE Game #11 – Dec. 29, 2003 Game #10 – Dec. 27, 2003 6 p.m. PST at Tucson, Ariz. 5:30 p.m. PST at Tempe, Ariz. CALIFORNIA Game #13 - Jan. 4, 2004 Game #26 - Feb. 26, 2004 Game #27 - Feb. 28, 2004 1 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. 7 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. 2 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. Game #19 – Jan. 29, 2004 Location: Tucson, Ariz. Location: Tempe, Ariz. 7 p.m. at Berkeley, Calif. Affiliation: NCAA 1 Affiliation: NCAA 1 Conference: Pacific-10 Conference: Pacific-10 Location: Berkeley, Calif. Enrollment: 35,000 Enrollment: 45,693 Affiliation: NCAA 1 Nickname: Wildcats Nickname: Sun Devils Conference: Pacific-10 Colors: Cardinal and Navy Colors: Maroon & Gold Enrollment: 33,000 Arena: McKale Center (14,545) Arena: Wells Fargo Arena (14,141) Nickname: Golden Bears Press Row Phone: 520-621-5291 Press Row Phone: 480-965-7274 Colors: Blue and Gold Website: www.arizonaathletics.com Website: www.TheSunDevils.com Arena: Haas Pavilion (11,877) Press Row Phone: 510-642-3098 Basketball SID: Mindy Claggett Basketball SID: Rhonda Lundin Website: www.calbears.com Phone: 520-621-4163 Phone: 480-965-9780 FAX: 520-621-2681 FAX: 480-965-5408 Basketball SID: Debbie Rosenfeld-Caparaz E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 510-642-3611 FAX: 510-643-7778 Athletic Director: Jim Livengood Athletic Director: Gene Smith E-mail: [email protected] Head Coach: Joan Bonvicini Head Coach: Charli Turner Thorne Record at Arizona: 214-139 (12 years) Record at Arizona State: 106-100 (7 years) Athletic -

2017 Opponents

2017 Opponents PortlaNnIKd ES tIantveit Taotiuornnaal ment Northwestern State Seton Hall Oklahoma Aug. 25, 3:30 p.m., Norman, Okla. Aug. 26, 9 a.m., Norman, Okla. Aug. 26, 6 p.m., Norman, Okla. Location ..............................Natchitoches, La. Location ...........................South Orange, N.J. Location ..................................Norman, Okla. Founded .................................................1884 Founded .................................................1856 Founded .................................................1890 Enrollment .............................................9,819 Enrollment .............................................9,700 Enrollment ...........................................31,250 Nickname .................................Lady Demons Nickname ............................................Pirates Nickname ..........................................Sooners Colors .........................Purple, White, Orange Colors ....................................Blue and White Colors ............................Crimson and Cream Conference ....................................Southland Conference .......................................Big East Conference ..........................................Big 12 Arena (Capacity) ....Prather Coliseum (3,900) Arena (Capacity) ..Walsh Gymnasium (2,600) Arena (Capacity) ......McCasland Field House President .............................Dr. Chris Maggio President ...................Mary Meehan (interim) (5,000) Athletics Director .........................Greg Burke Director -

Washington State

WASHINGTON STATE Women’s Basketball Washington State Athletic Media Relations • Bohler Addition 195 • Pullman, WA 99164 • (509) 335-2684 Jason Krump (Interim Women’s Basketball) - Office 509.335.8843 • [email protected] Bill Stevens, Director - Office: 509.335.4294 • Email: [email protected] Assistant Directors: Linda Chalich ([email protected]) • Craig Lawson ([email protected]) • Jessica Schmick ([email protected]) WSU Schedule Time (PT)/Result Cougars End Regular Season at USC and No. 9 UCLA 11/7 Lewis-Clark State (Exh.) W - 64-63 11/12 at Saint Mary’s L - 73-69 11/14 at UC Davis L - 77-38 11/18 at Portland L - 91-80 11/22 vs. No. 21 Nebraska L - 87-79 Waikiki Beach Marriott Rainbow Wahine Showdown Washington State Cougars (8-20, 6-10) 11/26 vs. No. 14 North Carolina L - 93-55 11/27 vs. Long Beach State W - 87-63 at USC 11/28 vs. Gonzaga L - 67-65 March 3 • Los Angeles, Calif. • 7 p.m. 12/5 vs. Nevada W - 67-54 12/7 vs. South Dakota St. L - 72-61 Cougars begin L.A. trip at USC 12/11 at Gonzaga L - 93-75 12/18 at Wyoming L - 63-43 at No. 9 UCLA 12/21 at San Diego State L - 66-57 12/31 vs. USC L - 72-57 March 5 • Los Angeles, Calif. • 2 p.m. 1/2 vs. No. 8 UCLA L - 80-55 1/6 at Oregon L - 77-72 Cougars face sixth ranked opponent of season 1/8 at Oregon State W - 58-50 1/14 vs. -

2007 Arizona Cactus Classic Program

32 Elite Teams - One Champion - You don't want to miss this. From May 18-20, 2007, the nation's most elite level travel basketball teams will compete in the 2nd Annual Arizona Cactus Classic presented by Precision Toyota & First Magnus, to be played at the University of Arizona's renowned McKale Memorial Center and Bear Down Gymnasium. TED BY Magnus PRESEN AND First Precision Toyota -20 2007 May 18 OFFICIAL PROGRAM TM Additional Support provided by: John Rowe, Tim Garrigan, George Rountree, Peter Evans, Alan Norville, Robert Hansen, Jack Handley, Nyal Leslie, Stanley Feldman, David & Susan Cohn, and Bob Bretz. 3 DAYS • 32 TEAMS • 79 GAMES • $10 BUCKS WHERE: McKale Memorial Center and Bear Down Gymnasium on the campus For ticket information and event details, visit: of The University of Arizona. www.azcactusclassic.com © Copyright 2007, Jim Storey Productions, LLC. Welcome to the Arizona Cactus Classic-2007 May 18, 2007 Dear Basketball Enthusiast: I say “Basketball Enthusiast” because if you are sponsoring, playing, scouting, or attending the 2nd Annual Arizona Cactus Classic then you really must be a basketball enthusiast. With 79 basketball games to be played in two and a half days, this event is truly for those who enjoy the wonderful game of basketball. Thank you for choosing to be a part of this unique basketball environment. I know that many of you have come to Tucson, Arizona from a long distance and I appreciate your willingness to be a part of this event. There have been many people and businesses that have helped make this event possible through their volunteerism and fi nancial support. -

UAF Annual & Endowment Report 2014

NOW IS THE TIME 2014 ANNUAL & ENDOWMENT REPORTS 2 UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT Letter from the Presidents & Chair 2 Private Gift / Grant Support 5 Gift Purpose 7 Gift Sources 9 Research 11 Academic Divisions 13 Capital Improvements 15 Unrestricted Gifts 17 Endowments 19 ENDOWMENT REPORT Endowment Market Value 21 Investment Approach and Goal 22 Investment Performance 23 Our Portfolio 24 Implementation and Positioning 25 Our Top Performing Allocations 26 Significant Actions Taken in 2014 28 Holdings by Asset Class 30 Investment Committee 31 LEADERSHIP Officers of the Board 32 Senior Staff 32 Board of Trustees 32 01 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA IS FILLED WITH GENEROSITY. It’s an institution where students, faculty and staff routinely help each other, where colleges and departments ask how they can support the community, and where alumni and friends consistently give of their time and resources. The value of generosity is even built into our mission as a super land grant and public university, charged with giving back to the people of Arizona and beyond. It is no secret that generosity feels good and fuels our souls. But now even academic studies show that generosity makes a huge difference in the quality of life for both the giver and receiver. When we give, our lives are happier and more fulfilled. And donating resources is one of the most powerful tools we have to inspire excellence. The value of generosity is at the root of the University of Arizona Foundation and the UA’s development program. In fiscal 2014, we were once again humbled and inspired by your contributions. -

Regional Plan Policies

Regional Plan Policies Adopted by the Pima County Board of Supervisors December 2001 Development Services Department Planning Division 201 North Stone Avenue Tucson, Arizona 85701-1317 (520) 740-6800 As Amended June 2012 This document, Regional Plan Policies, is one of three working documents of the Pima County Comprehensive Plan; see also Land Use Intensity Legend and Rezoning and Special Area Plan Policies. The complete Comprehensive Plan is available in the office of the Planning Division, Pima County Development Services Department. 2001 Pima County Comprehensive Plan Update Regional Plan Policies As Amended June 2012 Contents 1. Land Use Element Regional Plan Policies ......................................................................1 A. Administration .........................................................................................................1 B. Cultural Heritage .....................................................................................................4 C. Site Design and Housing ......................................................................................15 D. Public Services and Facilities ...............................................................................16 2. Circulation Element Regional Plan Policies ..................................................................22 3. Water Resources Element Regional Plan Policies .......................................................24 4. Open Space Element Regional Plan Policies ...............................................................32 -

The History of Arizona Women's Basketball

All-Time Series Records Series First Last Last Series First Last Last Opponent Record Meeting Meeting Result Opponent Record Meeting Meeting Result Alabama 0-1 11/29/87 11/29/87 L 74-80 Northern Illinois 2-1 12/22/92 12/15/99 W 78-46 American 0-0 12/6/03 Northwestern 1-0 3/23/96 3/23/96 W 79-63 Arizona State 28-36 2/2/73 2/22/03 W 72-52 Notre Dame 1-3 12/3/88 3/23/03 L 47-59 Arkansas 1-0 3/22/96 3/22/96 W 80-77 Oakland 2-0 12/29/88 12/29/89 W 75-65 Auburn 0-1 12/19/00 12/19/00 L 66-69 Ohio State 1-1 11/21/01 12/15/02 L 65-84 Baylor 2-0 12/22/81 12/29/97 W 86-73 Oklahoma 1-0 11/19/99 11/19/99 W 75-59 Biola 1-1 12/9/78 1/27/83 W 82-47 Oklahoma State 0-2 12/3/81 12/4/94 L 40-64 Boston College 0-1 12/30/87 12/30/87 L 64-79 Old Dominion 0-2 1/7/86 1/4/88 L 68-82 Bowling Green 1-0 12/8/00 12/8/00 W 99-43 Oregon 14-22 1/3/81 2/1/03 W 71-66 Brigham Young 3-5 2/24/73 11/18/00 W 76-71 Oregon State 18-19 12/7/83 3/8/03 W 70-56 California 25-13 12/17/77 3/1/03 W 68-51 Pacific 1-2 11/21/81 1/4/84 L 79-84 UC Irvine 3-3 12/14/81 11/28/93 W 73-67 Pacific Christian 1-0 12/10/81 12/10/81 W 84-60 UC Riverside 1-0 12/7/02 12/7/02 W 95-66 Pepperdine 5-2 12/29/82 11/25/02 W 80-68 UC Santa Barbara 6-4 1/3/80 1/14/02 L 80-94 Pittsburgh 0-1 12/2/01 12/2/01 L 80-81 Cal Poly-Pomona 0-6 11/19/77 11/20/82 L 66-74 Portland State 3-2 12/18/83 11/30/91 L 76-85 Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo 1-0 1/9/96 1/9/96 W 75-39 Providence 2-0 12/29/92 12/30/95 W 97-83 Cal State Fullerton 5-9 1/10/80 12/8/95 W 87-33 Puerto Rico-Mayaguez 1-0 12/20/00 12/20/00 W 105-41 Cal State Northridge 2-1 12/1/78 2/16/94 W 98-57 Purdue 0-2 12/20/97 11/19/98 L 58-65 Chico State 1-0 12/7/79 12/7/79 W 64-61 Rice 2-0 11/28/00 12/8/01 W 74-65 Cleveland State 0-1 11/28/82 11/28/82 L 43-61 Rutgers 0-2 1/2/88 3/14/99 L 47-90 Colorado 3-5 2/21/75 11/24/91 L 53-77 Sacramento State 1-0 12/17/94 12/17/94 W 105-50 Colorado State 6-2 2/22/75 12/6/99 W 89-75 St. -

2017-18 Pac-12 Women's Basketball Prospectus

NOTES 2017-18 PAC-12 BASKETBALL // PROSPECTUS 2017-18 PAC-12 WOMEN'S BASKETBALL QUICK REFERENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS Quick Reference ........................................1 ARIZONA UCLA 106 McKale Center • Tucson, AZ 85721-0096 Morgan Center • 325 Westwood Plaza TEAM INFORMATION .......................2-13 Office: (520) 621-4163 / Fax: (520) 621-2681 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1639 Arizona Wildcats ........................................2 http://www.arizonawildcats.com Office: (310) 206-6831 / Fax: (310) 825-8664 Arizona State Sun Devils .............................3 Head Coach: http://www.uclabruins.com Adia Barns (Arizona 1998) ......................Second Year Head Coach: California Golden Bears ..............................4 Record at Arizona/Years .................................14-16/1 Cori Close (UC Santa Barbara 1993) ...... Seventh Year Colorado Buffaloes .....................................5 Career Record/Years ......................................14-16/1 Record at UCLA/Years ..................................123-78/6 Oregon Ducks ............................................6 Women’s Basketball SID: Career Record/Years ....................................123-78/6 Oregon State Beavers .................................7 Adam Gonzales, Asst. Dir. .......................................... Women’s Basketball SID: ............................. [email protected] Ryan Finney, Assoc. Dir. [email protected] Stanford Cardinal .......................................8 UCLA Bruins ..............................................9 -

FIGHT of the WILDCAT: NO. 18 ARIZONA at NO. 1 OKLAHOMA 8 California L; 196.00 the No

OFFICIAL 2016 MEET NOTES Athletics Communications Services • McKale Center • 1 National Championship Drive • Room 106 • Tucson, Arizona • 85719 • ArizonaWildcats.com/Gymnastics Contact: Danielle Bracamonte • C: (520)227-8238 • O: (520)621-4163 • Email: [email protected] ► ScHEdulE and rESulTS ► THIS WEEK January Meet .....................................................................Arizona at Oklahoma 8 Michigan State W; 195.70 Site............................................................................Lloyd Noble Center Date ..................................................................................March 4, 2016 17 Texas Woman’s W; 193.475 Time ......................................................................................5:45 p.m. MST 23 UCLA L; 196.475 Network..................Fox Sports Oklahoma Plus and Fox College Sports Atlantic February LiveStats..........www.statbroadcast.com/events/statbroadcast.php?t=1&gid=okla 1 Utah L; 194. 85 FIGHT OF THE WILDCAT: NO. 18 ARIZONA AT NO. 1 OKLAHOMA 8 California L; 196.00 The No. 18 Arizona women’s gymnastics team will compete in their final 13 Stanford L; 196.15 road meet of the regular season this Friday, March 4 in Norman, Okla. The 22 Arizona State W; 196.375 meet against the No. 1 Sooners will be at 5:45 p.m. MST and will be aired on Fox Sports Oklahoma Plus and Fox College Sports Atlantic. 27 Washington W; 196.10 March LAST TIME ON THE ROAD 4 Oklahoma - Last time on the road the Wildcats faced rival Arizona State, on Feb. 22. The Wildcats defeated the Sun Devils 196.375-193.975. Sophomore Maddy 11 BYU - Cindric, led the team to their highest beam score of the season and a win over Arizona State Monday night. Cindric earned the beam title and a 19 Pac-12 Championships - career high 9.90 on the event, assisting the team to a 49.25. -

The Story of Bear Down Table of Contents

THE STORY OF BEAR DOWN TABLE OF CONTENTS University of Arizona Athletics’ most enduring tradition is the slogan Introductory Information and battle cry, “Bear Down.” Quick Facts ........................................................................................................... 2 Media Information ............................................................................................. 3 More than a casual piece of encouragement, the rally cry has roots over Roster/Pronunciations ................................................................................... 4-5 a century old, to the Roaring ‘20s, and pre-dates another venerated 2017 Arizona Football exhortation, “Win one for the Gipper,” by two years. Player Biographies ........................................................................................ 6-24 Head Coach Rich Rodriguez .....................................................................25-28 In the fall of 1926, John Byrd “Button” Salmon was the newly installed Assistant Coach Biographies ....................................................................29-34 student body president at the UA, a promising student and member Football Support Staff ...............................................................................35-37 of note of several of the school’s honor societies. He also was a varsity University President/Athletic Director ......................................................... 38 quarterback, a baseball catcher and generally acclaimed popular cam- University and Pac-12 Conference -

Columbia Chronicle (03/26/2001) Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Chronicle College Publications 3-26-2001 Columbia Chronicle (03/26/2001) Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle Part of the Journalism Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Chronicle (03/26/2001)" (March 26, 2001). Columbia Chronicle, College Publications, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle/508 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Chronicle by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. Spring Break The Chronicle goes Spectacular one-on-one with the '7-up yours guy' At a glance Problems plague Congress dormitory Residents say their phones often don' t By Joe Guiliani work, and their rooms are still not Contributing Editor equipped with cable TV. Many have had their toilets overflow, leaving Inside Columbia's new donnitory at rooms reeking of sewage. 18 E. Congress, the walls are a pristine Remodeling in the building apparent white. The new carpeting is clean, and ly ran behind schedule, and now, six the furniture in each room- a couch months later. workers arc still scram and two chairs- is soft and plush. bling to make repairs and finish the job. But look closer and you' II find cracks Oakes said the company who installed in the plaster, ceiling tiles turned a dis the building's plumbing fa iled to install gusting brown from leaking water. -

PAC-10 CONFERENCE PAC-12 CONFERENCE PAC-10 CONFERENCE1350 Treat Blvd., Suite 500, Walnut Creek, CA 94597 // PAC-12.COM // 925.932.4411 PAC-12 CONFERENCE

PAC-10 CONFERENCE PAC-12 CONFERENCE PAC-10 CONFERENCE1350 Treat Blvd., Suite 500, Walnut Creek, CA 94597 // PAC-12.COM // 925.932.4411 PAC-12 CONFERENCE 1350 Treat Blvd., Suite 500, Walnut Creek, CA 94597 // PAC-12.COM // 925.932.4411 For Immediate Release \\ Wednesday, April 17, 2013 Contact \\ Natalia Ciccone ([email protected]); Alex Kaufman ([email protected]) 2012-13 PAC-12 WOMEN’S BASKETBALL STANDINGS Conference Overall W L PCT H A W L PCT H A N STREAK LAST 5 TOP 10 TOP 25 Stanford*%^ 17 1 .944 8-1 9-0 33 3 .917 12-2 15-0 5-1 L1 4-1 3-2 10-3 California*^ 17 1 .944 8-1 9-0 32 4 .889 15-1 12-1 4-2 L1 4-1 1-2 7-4 UCLA^ 14 4 .778 7-2 7-2 26 8 .765 11-4 10-2 5-2 L1 3-2 1-6 4-6 Colorado^ 13 5 .722 7-2 6-3 25 7 .781 15-3 9-3 1-1 L2 3-2 1-5 1-6 Washington@ 11 7 .611 6-3 5-4 21 12 .636 11-5 9-6 1-1 L1 2-3 0-2 0-7 Utah@ 8 10 .444 5-4 3-6 23 14 .622 12-6 10-7 1-1 L1 4-1 0-4 0-7 USC 7 11 .389 3-6 4-5 11 20 .355 5-12 5-7 1-1 L1 2-3 0-6 0-11 Washington State 6 12 .333 3-6 3-6 11 20 .355 6-7 4-11 1-2 L1 1-4 0-3 1-8 Arizona State 5 13 .278 3-6 2-7 13 18 .419 7-8 4-8 2-2 L3 2-3 0-2 0-6 Arizona 4 14 .222 2-7 2-7 12 18 .400 5-8 6-8 1-2 L5 0-5 0-2 0-6 Oregon State 4 14 .222 2-7 2-7 10 21 .323 6-9 2-8 2-4 L2 1-4 0-5 0-11 Oregon 2 16 .111 1-8 1-8 4 27 .129 3-13 1-11 0-3 L5 0-5 0-5 0-10 * Pac-12 Co-Champions; Stanford earns No.