Continuous Popliteal Sciatic Nerve Block for Postoperative Pain Control at Home a Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Study Brian M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Policy: Hyperemesis Gravidarum Treatment Reference Number: PA.CP.MP.34 Effective Date: 01/18 Coding Implications Last Review Date: 04/18 Revision Log

Clinical Policy: Hyperemesis Gravidarum Treatment Reference Number: PA.CP.MP.34 Effective Date: 01/18 Coding Implications Last Review Date: 04/18 Revision Log Description Hyperemesis gravidarum is a term reserved to describe the most severe cases of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP). It results from severe nausea and vomiting, and the resultant inability to rehydrate and replenish nutritional reserves. A diagnosis of hyperemesis gravidarum is best made when it is based on objective findings such as moderate to large ketonuria and weight loss. Weight loss of 5% or greater is often described as diagnostic of hyperemesis gravidarum but this is not to suggest that measures to improve nausea and vomiting should not be undertaken prior to this. Hyperemesis gravidarum tends to begin earlier in pregnancy and last longer than those patients with less severe NVP. When the step-approach algorithm does not allow for continued adequate hydration of the patient, intravenous (IV) infusion or subcutaneous (SQ) micropump infusion of metoclopramide or ondansetron can allow for treatment until the patient can reliably take oral medications. The ability to perform activities of daily living, tolerate most food intake, and take oral medications are measures that objectively and subjectively instruct the practitioner as to the value of these therapies. When these therapies have allowed the patient to return to the above states of function, they can be discontinued. Oral therapies can be used in conjunction with IV and SQ infusion if tolerated. There is not a place for continuous, long-term IV or SQ infusion of medications to manage hyperemesis if the patient is functioning as described above. -

Errors Associated with Oxytocin

February 2020 Volume 18 Issue 2 Now Available from ISMP Errors associated with oxytocin use: A multi- Expanded Smart Pump Guidelines organization analysis by ISMP and ISMP Canada We have just released revised and expanded Guidelines for Optimizing Safe ntravenous (IV) oxytocin used antepartum is indicated to induce labor in patients Implementation and Use of Smart Infusion with a medical indication, to stimulate or reinforce labor in selected cases of uterine Pumps to provide strategies for address - Iinertia, and as an adjunct in the management of incomplete or inevitable abortion. ing potential barriers and integrating this Used postpartum, IV oxytocin is indicated to produce uterine contractions during technology with other electronic systems. expulsion of the placenta and to control postpartum bleeding or hemorrhage. However, The expanded guidelines cover a broad improper administration of oxytocin can cause hyperstimulation of the uterus, which in scope of smart infusion pump usage in turn can result in fetal distress, the need for an emergency cesarean section, or uterine both inpatient and ambulatory settings, rupture. Sadly, a few maternal, fetal, and neonatal deaths have been reported. including perioperative, procedural, and radiology locations. The expanded guide - In October 2019, ISMP Canada published a multi-incident analysis 1 to identify oppor - lines also include recommendations to tunities to improve the safe use of this high-alert medication. A total of 144 reports of employ smart infusion pumps with dose incidents associated with oxytocin were analyzed from voluntary reports submitted error-reduction systems for plain IV fluid to ISMP Canada and the Canadian National System for Incident Reporting (NSIR) infusions. -

A Portable Mechanical Pump Providing Over Four Days of Patient-Controlled Analgesia by Perineural Infusion at Home

A Portable Mechanical Pump Providing Over Four Days of Patient-Controlled Analgesia by Perineural Infusion at Home Brian M. Ilfeld, M.D., and F. Kayser Enneking, M.D. Background and Objectives: Local anesthetics infused via perineural catheters postoperatively decrease opioid use and side effects while improving analgesia. However, the infusion pumps described for outpatients have been limited by several factors, including the following: limited local anesthetic reservoir volume, fixed infusion rate, and inability to provide patient-controlled doses of local anesthetic in combination with a continuous infusion. We describe a patient undergoing open rotator cuff repair who was discharged home with an interscalene perineural catheter and a mechanical infusion pump that allowed a variable rate of continuous infusion, as well as patient-controlled boluses of local anesthetic for over 4 days. Case Report: A 77-year-old woman, who had previously required a 3-day hospital admission for acute postoperative pain following an open repair of her left rotator cuff, presented for an open repair of her contralateral rotator cuff. Preoperatively she received an interscalene block and perineural catheter. After the procedure she was discharged home with a portable pump that infused ropivacaine continuously at a rate of 6 mL/h and allowed a 2-mL patient-controlled bolus every 20 minutes (550-mL reservoir). The basal infusion was decreased, as tolerated, by having the patient reprogram the pump with instructions given over the telephone. Without the use of any oral opioids, the patient scored her surgical pain 0 to 1 (on a scale of 0 to 10) while at rest and 2 to 3 for 2 physical therapy sessions during which she used the bolus function to reinforce her analgesia. -

ACR Manual on Contrast Media

ACR Manual On Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media Preface 2 ACR Manual on Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media © Copyright 2021 American College of Radiology ISBN: 978-1-55903-012-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page 1. Preface 1 2. Version History 2 3. Introduction 4 4. Patient Selection and Preparation Strategies Before Contrast 5 Medium Administration 5. Fasting Prior to Intravascular Contrast Media Administration 14 6. Safe Injection of Contrast Media 15 7. Extravasation of Contrast Media 18 8. Allergic-Like And Physiologic Reactions to Intravascular 22 Iodinated Contrast Media 9. Contrast Media Warming 29 10. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Contrast 33 Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Adults 11. Metformin 45 12. Contrast Media in Children 48 13. Gastrointestinal (GI) Contrast Media in Adults: Indications and 57 Guidelines 14. ACR–ASNR Position Statement On the Use of Gadolinium 78 Contrast Agents 15. Adverse Reactions To Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media 79 16. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) 83 17. Ultrasound Contrast Media 92 18. Treatment of Contrast Reactions 95 19. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially 97 Pregnant Patients 20. Administration of Contrast Media to Women Who are Breast- 101 Feeding Table 1 – Categories Of Acute Reactions 103 Table 2 – Treatment Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 105 Children Table 3 – Management Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 114 Adults Table 4 – Equipment For Contrast Reaction Kits In Radiology 122 Appendix A – Contrast Media Specifications 124 PREFACE This edition of the ACR Manual on Contrast Media replaces all earlier editions. -

Performance Drug List - Standard Control

October 2020 Performance Drug List - Standard Control The CVS Caremark® Performance Drug List - Standard Control is a guide within select therapeutic categories for clients, plan members and health care providers. Generics should be considered the first line of prescribing. If there is no generic available, there may be more than one brand-name medicine to treat a condition. These preferred brand-name medicines are listed to help identify products that are clinically appropriate and cost-effective. Generics listed in therapeutic categories are for representational purposes only. This is not an all-inclusive list. This list represents brand products in CAPS, branded generics in upper- and lowercase Italics, and generic products in lowercase italics. PLAN MEMBER HEALTH CARE PROVIDER Your benefit plan provides you with a prescription benefit program Your patient is covered under a prescription benefit plan administered by CVS Caremark. Ask your doctor to consider administered by CVS Caremark. As a way to help manage health prescribing, when medically appropriate, a preferred medicine from care costs, authorize generic substitution whenever possible. If you this list. Take this list along when you or a covered family member believe a brand-name product is necessary, consider prescribing a sees a doctor. brand name on this list. Please note: Please note: • Your specific prescription benefit plan design may not cover • Generics should be considered the first line of prescribing. certain products or categories, regardless of their appearance in • The member's prescription benefit plan design may alter this document. Products recently approved by the U.S. Food 1 and Drug Administration (FDA) may not be covered upon coverage of certain products or vary copay amounts based on release to the market. -

Coram Infusion Patient Resource Guide

Infusion Patient Resource Guide Coram Patient Resource Guide 1 Welcome to Coram At Coram® CVS Specialty® Infusion Services (Coram), we’re here to help make things a little easier. We know that starting infusion therapy at home will require some changes for you. At first, you may feel stressed—but we’re ready to help. Coram will provide ongoing education, care and support. We want to help you achieve success with your infusion therapy. We’re here for you every step of the way. Each day, skilled Coram nurses and dietitians work together. We provide complex infusion care to thousands of patients. The skilled staff at Coram will work as a team, along with your doctor, to arrange all aspects of your care. Your Coram care team can be reached 24 hours a day, every day, to answer questions about your health, medications, equipment or supplies. At every turn, Coram will help you stay on your path to better health. We work hard to make sure you always get the best care and personalized support to help you meet your health care needs. This guide will introduce you to the Coram team and provide you with facts about your infusion therapy. Please use this guide as a resource during your therapy. 1 Contents Your Home Infusion Therapy Support ................................. 3 Managing Your Medication and Supplies .............................. 3 Waste Disposal ..................................................... 4 Infusion Therapy .................................................... 5 How to Care For and Manage Your IV Catheter ........................ 6 How to Administer Your Infusion Therapy ............................. 7 Steps for Success with Your Home Infusion Therapy ................... 8 How to Contact Coram ............................................. -

Smart Pumps, Smart Management, Safe Patients When Organizations and Clinicians Team Up, Patients Are Protected

Smart pumps, smart management, safe patients When organizations and clinicians team up, patients are protected. By Dawn Berndt, DNP, RN, CRNI®, and Marlene Steinheiser, PhD, RN, CRNI® MEDICATION administration errors are among the most vexing and costly events in health- care. For the patient, errors related to thera- peutic infusions can present grave conse- quences, including therapy disruption, over- or underdosing that reduces the therapeutic ef- fect, debilitating injury, or death. In 2020, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) published Guidelines for Optimizing Safe Im- plementation and Use of Smart Infusion Pumps. This resource, compiled and reviewed by clinical experts, outlines the components necessary for developing an organizational in- Bi-directional benefits and challenges Bi-directional smart infusion pumps raise frastructure that promotes safe patient care us- the standard of care but also present some challenges. ing smart infusion pump technology. In April 2021, The Joint Commission released a Sen- Benefits tinel Event Alert on smart infusion pumps that Bi-directional smart infusion pumps • also contains useful strategies. remove the human factor from manually Smart infusion pumps are sophisticated programming the infusion pump computer systems that communicate within a • connect the pump channel, medication or- der, and patient network, using software and hardware de- • promote safe medication administration signed to send the exact amount of medica- based on the provider’s order tion at a precise rate to each patient. At the in- • facilitate consistent and timely documenta- terface between the infusion pump and the tion of each infusion in the patient’s elec- nurse, critical decisions are made, presump- tronic health record. -

University of Michigan Home Care Services

1 GEMSTAR -6-NEONATE Administration of IV Medications Using the GemStar Pump Drug Name: ______________________________________ FLUSHING: Saline Volume and Rate: __________________________________ Drug Saline Schedule: _________________________________________ Heparin KEY POINTS: 1. Always wash your hands with an antibacterial soap or antiseptic hand gel before any procedure for 15 seconds. Do not touch anything dirty, such as your clothes, glasses or skin after washing your hands. If you do, rewash them. 2. If your medication needs refrigeration, remove at least 2 hours before using. 3. Check the bags and syringes for leaks, expiration dates, color changes and floating materials. If any of these occur, set aside and use another. Notify HomeMed. 4. Always check the bag label for your name, drug name, dose and how frequently the drug should be given. If the information does not match, call HomeMed immediately. 5. Work at a comfortable pace. The risk of contamination increases if you rush. 6. Change your IV tubing every 3 days. Labels will be provided. 7. YOU WILL PRIME TUBING WITH ONE IV MEDICATION BAG AND CHANGE TO ANOTHER FOR YOUR DOSE. YOU WILL DO THIS ON TUBING CHANGE DAYS ONLY. SUPPLIES: (2) Prefilled IV medication bag (1) GemStar IV tubing (remove from package) (2) Prefilled saline flush syringes (remove from package) (1) Prefilled Heparin lock syringe (remove from package) GemStar pump (3) Blunt needles (2) Locking blunt cannulas (“winged adaptors”) (4) Alcohol wipes Household cleaner (such as bleach, alcohol or dish soap) & paper towels University of Michigan Hospitals and Health Centers. All Rights Reserved. PROCEDURE: 1. Place a trash can next to your work area. -

Infusion Pumps for Medication & Parenteral Fluid

TITLE INFUSION PUMPS FOR MEDICATION & PARENTERAL FLUID ADMINISTRATION SCOPE DOCUMENT # Provincial, Clinical PS-70-01 APPROVAL LEVEL Executive Leadership Team SPONSOR INITIAL EFFECTIVE DATE Provincial Medication Management Committee January 04, 2016 CATEGORY REVISED Patient Safety Not applicable PARENT DOCUMENT TYPE & TITLE Infusion Pumps for Medication & Parenteral Fluid Administration Policy Level 1 NOTE: The first appearance of terms in bold in the body of this document (except titles) are defined terms – please refer to the Definitions section. If you have any questions or comments regarding the information in this procedure, please contact the Policy & Forms Department at [email protected]. The Policy & Forms website is the official source of current approved policies, procedures, directives, and practice support documents. OBJECTIVES • To describe the process for the management of an infusion pump involved in an adverse event or close call. • To outline the process for the management of soft stops/limits and hard stops/limits for infusion pumps with dose error reduction software (DERS). APPLICABILITY Compliance with this procedure is required by all Alberta Health Services employees, members of the medical and midwifery staffs, students, volunteers, and other persons acting on behalf of Alberta Health Services (including contracted service providers as necessary). This procedure does not limit any legal rights to which you may otherwise be entitled. PROCEDURE ELEMENTS 1. Education and Support 1.1 Refer to the Standards -

User Manual Is Delivered Subject to the Conditions and Restrictions Listed in This Section

Important Notice The Sapphire Infusion Pump User Manual is delivered subject to the conditions and restrictions listed in this section. Clinicians, qualified hospital staff, and home users should read the entire User Manual prior to operating the Sapphire pump in order to fully understand the functionality and operating procedures of the pump and its accessories. • Healthcare professionals should not disclose to the patient the pump's security codes, Lock levels, or any other information that may allow the patient access to all programming and operating functions. • Improper programming may cause injury to the patient. • Home users of the Sapphire pump should be instructed by a certified home healthcare provider or clinician on the proper use of this pump. Prescription Notice Federal United States law restricts this device for sale by or on the order of a physician only {21 CFR 801.109(b) (1)}. The Sapphire pump is for use at the direction of, or under the supervision of, licensed physicians and/or licensed healthcare professionals who are trained in the use of the pump and in the administration of blood, medication and parenteral nutrition. The instructions for use presented in this manual should in no way supersede established medical protocol concerning patient care. Copyright, Trademark and Patent Information © 2015, Q Core Medical Ltd. All right reserved. Sapphire and Q Core (with or without logos) are trademarks of Q Core Medical Ltd. The design, pumping mechanism and other features of the Sapphire pump are protected under one or more US and Foreign Patents. 1 Sapphire Infusion Pump User Manual Disclaimer The information in this manual has been carefully examined and is believed to be reliable. -

How Safety Features Make Or Break Infusion Pump Design

Expert View HOW SAFETY FEATURES MAKE OR BREAK INFUSION PUMP DESIGN In this article, Charlotte Harvey, Medical Sector Manager, and Tim Frearson, Senior Consultant, both of Sagentia, overview the safety systems required when designing an infusion pump system, with a focus on free-flow prevention, occlusion detection and air-in-line detection. Infusion pumps are complex New entrants to the world of infusion pumps electromechanical devices used to deliver will find that safety features are a major fluids into a patient’s body in a controlled driving force behind their design, as they manner. They typically serve the needs of control every aspect of a user’s interaction hospital-bound patients, where life-saving with the device and have the potential to make medication is normally delivered via it unusable when things go wrong. This article intravenous infusion. With the desire for reviews different pump types, their typical patients to be able to manage their own safety features, and the implementation of conditions outside of a hospital setting, three of the most important safety features in together with the trend towards continuous infusion pump design. drug delivery, the use of at-home, ambulatory and wearable infusion pumps is on the rise. IDENTIFYING THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF INFUSION PUMP “Many of the learnings There are several types of infusion device. The type of pump used is dependent on from volumetric and the patient’s needs, such as the required syringe pumps are also volume and the speed of the desired relevant to ambulatory or infusion. And different types of pump are more or less suited to hospital, at-home or wearable pumps, as they ambulatory usage. -

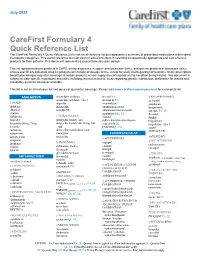

Carefirst Formulary 4 Quick Reference List

July 2021 CareFirst Formulary 4 Quick Reference List The CareFirst Formulary 4 Quick Reference List is not an all-inclusive list but represents a summary of prescribed medications within select therapeutic categories. This useful reference tool can assist medical providers in selecting therapeutically appropriate and cost-effective products for their patients. This document represents a closed formulary plan design. This list represents brand products in CAPS, branded generics in upper- and lowercase Italics, and generic products in lowercase italics. Unless specifically indicated, drug list products will include all dosage forms, except for orally disintegrating formulations. Some prescription benefit plan designs may alter coverage of certain products or vary copay amounts based on the condition being treated. This document is subject to state-specific regulations and rules, including, but not limited to, those regarding generic substitution, preference for brands and mandatory generics whenever available. This list is not an all-inclusive list and does not guarantee coverage. Please visit www.carefirst.com/myaccount for a complete list. ANALGESICS amoxicillin-clavulanate linezolid PA § ANTIARRHYTHMICS amoxicillin-clavulanate ext-rel linezolid inj PA acebutolol § NSAIDs ampicillin metronidazole amiodarone diclofenac dicloxacillin nitrofurantoin ext-rel disopyramide diflunisal penicillin VK nitrofurantoin macrocrystals dofetilide PA, SP etodolac praziquantel QL, PA flecainide § TETRACYCLINES flurbiprofen rifabutin ibutilide doxycycline