(OSS/FS)? Look at the Numbers!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MORF: a Framework for Predictive Modeling and Replication at Scale with Privacy-Restricted MOOC Data

MORF: A Framework for Predictive Modeling and Replication At Scale With Privacy-Restricted MOOC Data Josh Gardner, Christopher Brooks Juan Miguel Andres, Ryan S. Baker School of Information Graduate School of Education The University of Michigan The University of Pennsylvania Ann Arbor, USA Philadelphia, USA fjpgard, [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Big data repositories from online learning plat- ing. For example, several works have explored prediction forms such as Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) rep- of various student outcomes using behavioral, linguistic, resent an unprecedented opportunity to advance research and assignment data from MOOCs to evaluate and predict on education at scale and impact a global population of learners. To date, such research has been hindered by poor various student outcomes including course completion [1], reproducibility and a lack of replication, largely due to three [2], [3], assignment grades [4], Correct on First Attempt types of barriers: experimental, inferential, and data. We (CFA) submissions [5], student confusion [6], and changes present a novel system for large-scale computational research, in behavior over time [7]. A key area of research has been the MOOC Replication Framework (MORF), to jointly address methods for feature engineering, or extracting structured these barriers. We discuss MORF’s architecture, an open- source platform-as-a-service (PaaS) which includes a simple, information from raw data (i.e. clickstream server logs, flexible software API providing for multiple modes of research natural language in discussion posts) [8]. (predictive modeling or production rule analysis) integrated with a high-performance computing environment. All experi- B. -

Ubuntu Kung Fu

Prepared exclusively for Alison Tyler Download at Boykma.Com What readers are saying about Ubuntu Kung Fu Ubuntu Kung Fu is excellent. The tips are fun and the hope of discov- ering hidden gems makes it a worthwhile task. John Southern Former editor of Linux Magazine I enjoyed Ubuntu Kung Fu and learned some new things. I would rec- ommend this book—nice tips and a lot of fun to be had. Carthik Sharma Creator of the Ubuntu Blog (http://ubuntu.wordpress.com) Wow! There are some great tips here! I have used Ubuntu since April 2005, starting with version 5.04. I found much in this book to inspire me and to teach me, and it answered lingering questions I didn’t know I had. The book is a good resource that I will gladly recommend to both newcomers and veteran users. Matthew Helmke Administrator, Ubuntu Forums Ubuntu Kung Fu is a fantastic compendium of useful, uncommon Ubuntu knowledge. Eric Hewitt Consultant, LiveLogic, LLC Prepared exclusively for Alison Tyler Download at Boykma.Com Ubuntu Kung Fu Tips, Tricks, Hints, and Hacks Keir Thomas The Pragmatic Bookshelf Raleigh, North Carolina Dallas, Texas Prepared exclusively for Alison Tyler Download at Boykma.Com Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their prod- ucts are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters or in all capitals. The Pragmatic Starter Kit, The Pragmatic Programmer, Pragmatic Programming, Pragmatic Bookshelf and the linking g device are trademarks of The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC. -

MICHAEL STRÖDER Phone +49 721 8304316 [email protected]

Klauprechtstr. 11 D-76137 Karlsruhe, Germany MICHAEL STRÖDER Phone +49 721 8304316 [email protected] http://www.stroeder.com/ OBJECTIVE A contractor position as a consultant for planning and implementing identity and access management (IAM), security infrastructures (PKI, directory services) and related applications. CAPABILITIES • Planning / designing architectures and implementing mechanisms for secure usage of IT services (PKI, SSL, S/MIME, VPN, LDAP, Identity & Access Management (IAM), Single Sign-On, Firewalls) • Designing, implementing and automatically installing/configuring (DevOps) secure software (e.g. web applications), object-oriented software design and programming (e.g. Python) • System integration and user management in large and complex environments • Training and workshops EXPERIENCE Diverse Projekte (05/2019..12/2020) • Concepts, development, pilots, deployment, integration • Development: Python, migration to Python 3 • Software: OpenLDAP/Æ-DIR, keycloak, integration MS AD • Configuration management: ansible, puppet • Operating systems: Debian Linux, CentOS/RHEL, SLE • Hardening Linux: AppArmor, systemd IT-company Data Science (10/2019..09/2020) • Improved and updated internal IAM based on Æ-DIR (OpenLDAP) • Configuration management with ansible • 3rd-level support for operations As a trainer (05/2019..02/2020) • Python for system administrators • LDAP/OpenLDAP/IAM Versicherung (03/2019) • Implemented secure and highly available configuration of OpenLDAP servers used for customer user accounts • Implemented puppet -

SDM 7.61 Open Source and Third-Party Licenses

Structured Data Manager Software Version 7.61 Open Source and Third-party Licenses Document Release Date: February 2019 Software Release Date: February 2019 Open Source and Third-party Licenses Legal notices Copyright notice © Copyright 2017-2019 Micro Focus or one of its affiliates. The only warranties for products and services of Micro Focus and its affiliates and licensors (“Micro Focus”) are set forth in the express warranty statements accompanying such products and services. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. Micro Focus shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. Adobe™ is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Microsoft® and Windows® are U.S. registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. UNIX® is a registered trademark of The Open Group. This product includes an interface of the 'zlib' general purpose compression library, which is Copyright © 1995-2002 Jean-loup Gailly and Mark Adler. Documentation updates The title page of this document contains the following identifying information: l Software Version number, which indicates the software version. l Document Release Date, which changes each time the document is updated. l Software Release Date, which indicates the release date of this version of the software. You can check for more recent versions of a document through the MySupport portal. Many areas of the portal, including the one for documentation, require you to sign in with a Software Passport. If you need a Passport, you can create one when prompted to sign in. Additionally, if you subscribe to the appropriate product support service, you will receive new or updated editions of documentation. -

An Introduction to Software Licensing

An Introduction to Software Licensing James Willenbring Software Engineering and Research Department Center for Computing Research Sandia National Laboratories David Bernholdt Oak Ridge National Laboratory Please open the Q&A Google Doc so that I can ask you Michael Heroux some questions! Sandia National Laboratories http://bit.ly/IDEAS-licensing ATPESC 2019 Q Center, St. Charles, IL (USA) (And you’re welcome to ask See slide 2 for 8 August 2019 license details me questions too) exascaleproject.org Disclaimers, license, citation, and acknowledgements Disclaimers • This is not legal advice (TINLA). Consult with true experts before making any consequential decisions • Copyright laws differ by country. Some info may be US-centric License and Citation • This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). • Requested citation: James Willenbring, David Bernholdt and Michael Heroux, An Introduction to Software Licensing, tutorial, in Argonne Training Program on Extreme-Scale Computing (ATPESC) 2019. • An earlier presentation is archived at https://ideas-productivity.org/events/hpc-best-practices-webinars/#webinar024 Acknowledgements • This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR), and by the Exascale Computing Project (17-SC-20-SC), a collaborative effort of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science and the National Nuclear Security Administration. • This work was performed in part at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is managed by UT-Battelle, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725. • This work was performed in part at Sandia National Laboratories. -

Openoffice.Org News Highlights Table of Contents Octo Ber 2004

OpenOffice.org News Highlights Table of Contents Octo ber 2004 ................................................................................................ R eplacing FrameMaker with OOo Writer ............................................................................................. Ger mans claim Linux lowers costs ......................................................................................................... Ope n approach offers Mindef more choice ............................................................................................ Ball mer calls for horse-based attack on Star Office ............................................................................... Ope n for Business - The 2004 OfB Choice Awards .............................................................................. Sep tember 2004 ............................................................................................ Ope nOffice.org reveals marketing ambitions ......................................................................................... No nprofit brings Linux and open source to Hawaii ............................................................................... UK charity builds Linux network on a shoestring .................................................................................. N SW opens door to Linux offers ............................................................................................................ L eading Edge Forum Report 2004 - Open Source: Open for Business ................................................. -

Open Source Projects As Incubators of Innovation

RESEARCH CONTRIBUTIONS TO ORGANIZATIONAL SOCIOLOGY AND INNOVATION STUDIES / STUTTGARTER BEITRÄGE ZUR ORGANISATIONS- UND INNOVATIONSSOZIOLOGIE SOI Discussion Paper 2017-03 Open Source Projects as Incubators of Innovation From Niche Phenomenon to Integral Part of the Software Industry Jan-Felix Schrape Institute for Social Sciences Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies Jan-Felix Schrape Open Source Projects as Incubators of Innovation. From Niche Phenomenon to Integral Part of the Software Industry. SOI Discussion Paper 2017-03 University of Stuttgart Institute for Social Sciences Department of Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies Seidenstr. 36 D-70174 Stuttgart Editor Prof. Dr. Ulrich Dolata Tel.: +49 711 / 685-81001 [email protected] Managing Editor Dr. Jan-Felix Schrape Tel.: +49 711 / 685-81004 [email protected] Research Contributions to Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies Discussion Paper 2017-03 (May 2017) ISSN 2191-4990 © 2017 by the author(s) Jan-Felix Schrape is senior researcher at the Department of Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies, University of Stuttgart (Germany). [email protected] Additional downloads from the Department of Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies at the Institute for Social Sciences (University of Stuttgart) are filed under: http://www.uni-stuttgart.de/soz/oi/publikationen/ Abstract Over the last 20 years, open source development has become an integral part of the software industry and a key component of the innovation strategies of all major IT providers. Against this backdrop, this paper seeks to develop a systematic overview of open source communities and their socio-economic contexts. I begin with a recon- struction of the genesis of open source software projects and their changing relation- ships to established IT companies. -

Linux and Free Software: What and Why?

Linux and Free Software: What and Why? (Qué son Linux y el Software libre y cómo beneficia su uso a las empresas para lograr productividad económica y ventajas técnicas?) JugoJugo CreativoCreativo Michael Kerrisk UniversidadUniversidad dede SantanderSantander UDESUDES © 2012 Bucaramanga,Bucaramanga, ColombiaColombia [email protected] 77 JuneJune 20122012 http://man7.org/ man7.org 1 Who am I? ● Programmer, educator, and writer ● UNIX since 1987; Linux since late 1990s ● Linux man-pages maintainer since 2004 ● Author of a book on Linux programming man7.org 2 Overview ● What is Linux? ● How are Linux and Free Software created? ● History ● Where is Linux used today? ● What is Free Software? ● Source code; Software licensing ● Importance and advantages of Free Software and Software Freedom ● Concluding remarks man7.org 3 ● What is Linux? ● How are Linux and Free Software created? ● History ● Where is Linux used today? ● What is Free Software? ● Source code; Software licensing ● Importance and advantages of Free Software and Software Freedom ● Concluding remarks man7.org 4 What is Linux? ● An operating system (sistema operativo) ● (Operating System = OS) ● Examples of other operating systems: ● Windows ● Mac OS X Penguins are the Linux mascot man7.org 5 But, what's an operating system? ● Two definitions: ● Kernel ● Kernel + package of common programs man7.org 6 OS Definition 1: Kernel ● Computer scientists' definition: ● Operating System = Kernel (núcleo) ● Kernel = fundamental program on which all other programs depend man7.org 7 Programs can live -

Producing Open Source Software How to Run a Successful Free Software Project

Producing Open Source Software How to Run a Successful Free Software Project Karl Fogel Producing Open Source Software: How to Run a Successful Free Software Project by Karl Fogel Copyright © 2005-2018 Karl Fogel, under the CreativeCommons Attribution-ShareAlike (4.0) license. Version: 2.3098 Home site: http://producingoss.com/ Dedication This book is dedicated to two dear friends without whom it would not have been possible: Karen Under- hill and Jim Blandy. i Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................. vi Why Write This Book? ............................................................................................... vi Who Should Read This Book? .................................................................................... vii Sources ................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... viii For the first edition (2005) ................................................................................ viii For the second edition (2017) ............................................................................... x Disclaimer .............................................................................................................. xiii 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

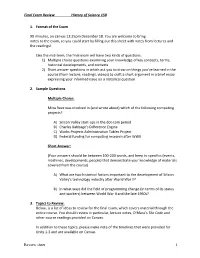

Final Exam Review History of Science 150

Final Exam Review History of Science 150 1. Format of the Exam 90 minutes, on canvas 12:25pm December 18. You are welcome to bring notes to the exam, so you could start by filling out this sheet with notes from lectures and the readings! Like the mid-term, the final exam will have two kinds of questions. 1) Multiple choice questions examining your knowledge of key concepts, terms, historical developments, and contexts 2) Short answer questions in which ask you to draw on things you’ve learned in the course (from lecture, readings, videos) to craft a short argument in a brief essay expressing your informed issue on a historical question 2. Sample Questions Multiple Choice: Mina Rees was involved in (and wrote about) which of the following computing projects? A) Silicon Valley start-ups in the dot-com period B) Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine C) Works Projects Administration Tables Project D) Federal funding for computing research after WWII Short Answer: (Your answers should be between 100-200 words, and keep to specifics (events, machines, developments, people) that demonstrate your knowledge of materials covered from the course) A) What are two historical factors important to the development of Silicon Valley’s technology industry after World War II? B) In what ways did the field of programming change (in terms of its status and workers) between World War II and the late 1960s? 3. Topics to Review: Below, is a list of ideas to review for the final exam, which covers material through the entire course. You should review in particular, lecture notes, O’Mara’s The Code and other course readings provided on Canvas. -

Linux at 25 PETERHISTORY H

Linux at 25 PETERHISTORY H. SALUS Peter H. Salus is the author of A n June 1991, at the USENIX conference in Nashville, BSD NET-2 was Quarter Century of UNIX (1994), announced. Two months later, on August 25, Linus Torvalds announced Casting the Net (1995), and The his new operating system on comp.os.minix. Today, Android, Google’s Daemon, the Gnu and the Penguin I (2008). [email protected] version of Linux, is used on over two billion smartphones and other appli- ances. In this article, I provide some history about the early years of Linux. Linus was born into the Swedish minority of Finland (about 5% of the five million Finns). He was a “math guy” throughout his schooling. Early on, he “inherited” a Commodore VIC- 20 (released in June 1980) from his grandfather; in 1987 he spent his savings on a Sinclair QL (released in January 1984, the “Quantum Leap,” with a Motorola 68008 running at 7.5 MHz and 128 kB of RAM, was intended for small businesses and the serious hobbyist). It ran Q-DOS, and it was what got Linus involved: One of the things I hated about the QL was that it had a read-only operating system. You couldn’t change things ... I bought a new assembler ... and an editor.... Both ... worked fine, but they were on the microdrives and couldn’t be put on the EEPROM. So I wrote my own editor and assembler and used them for all my programming. Both were written in assembly language, which is incredibly stupid by today’s standards. -

Annex I Definitions

Annex I Definitions Free and Open Source Software (FOSS): Software whose source code is published and made available to the public, enabling anyone to copy, modify and redistribute the source code without paying royalties or fees. Open source code evolves through community cooperation. These communities are composed of individual programmers and users as well as very large companies. Some examples of open source initiatives are GNU/Linux, Eclipse, Apache, Mozilla, and various projects hosted on SourceForge1 and Savannah2 Web sites. Proprietary software -- Software that is distributed under commercial licence agreements, usually for a fee. The main difference between the proprietary software licence and the open source licence is that the recipient does not normally receive the right to copy, modify, redistribute the software without fees or royalty obligations. Something proprietary is something exclusively owned by someone, often with connotations that it is exclusive and cannot be used by other parties without negotiations. It may specifically mean that the item is covered by one or more patents, as in proprietary technology. Proprietary software means that some individual or company holds the exclusive copyrights on a piece of software, at the same time denying others access to the software’s source code and the right to copy, modify and study the software. Open standards -- Software interfaces, protocols, or electronic formats that are openly documented and have been accepted in the industry through either formal or de facto processes, which are freely available for adoption by the industry. The open source community has been a leader in promoting and adopting open standards. Some of the success of open source software is due to the availability of worldwide standards for exchanging information, standards that have been implemented in browsers, email systems, file sharing applications and many other tools.