The Theory and Practice of Misspelling : a Linguistic Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Psychology of Money

The Psychology of Money Adrian Furnham Professor of Psychology e-mail: [email protected] SOME DEFINITIONS • Psychologist: – Man who goes to a strip show and looks at the audience. • Psychology: – Study of the id by the odd. • Psychologists’ greeting each other: – “You’re fine; how am I? • Business guru – Word used by journalists because they can’t spell charlatan. • Business consultant: – A simple organism designed to translate bullshit into air-miles. • Psychologist: • The next person you start talking to after you start talking to yourself. • Psychologist: • A professional who asks you a lot of expensive questions your partner asks you for nothing. • Psychologist: • A person who studies the problems of others in an attempt to understand their own problems. • Psychiatrist: • A doctor who can’t stand the sight of blood. • Psychotherapy: • The art of teaching people how to stand on their own feet while reclining on couches. • Psychoanalysis • The science that enables us to correct faults by confessing our parent's shortcomings. Is Money a Taboo Topic? • Rich people, who dictate etiquette, eschew discussing their money lest the poor figure out how to get it for themselves. Or because friends and relatives might want it or become envious of it. • It is superstitious to talk of money: it means it could be taken away. • Boasting about money could encourage envious others to inform tax authorities. • On some levels we know our attitudes to money reveal a lot about us which we would rather keep private. Five topics 1. Money at work 2. Emotional associations of money. 3. Learning about money. -

Jinx! – LED Matrix Control

Jinx! – LED Matrix Control User Manual Version 0.95a © 2013 Sven Karschewski http://www.live-leds.de Jinx! – LED Matrix Control Table of Contents Features ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Quick start ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Matrix Size ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Output Devices .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Patch Matrix .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Start Output ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Main Window .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Effect Generators .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Copy and Paste Effects ................................................................................................................................. -

CREATING FIRE-RESISTANT PROPERTIES and COMMUNITIES About

F I R E S C A P I N G DOUGLAS KENT MS, MLA CREATING FIRE-RESISTANT PROPERTIES AND COMMUNITIES About B&W by: Frederic Larson, The San Francisco Chronicle HISTORY CURRENTLY Photo by the Press Democrat, Oct. 2017 The Problem • Megafires, firestorms and fire tornados are now more common. • Scientists, fire professionals and ecologists believe the worst is still ahead. • The two primary reasons driving the increase in frequency and ferocity are well known: The Problem 1. Warming Planet Warmer temperatures create drier and more ignitable landscapes. Warming also increases the likelihood of fire weather—those exceptionally hot, low humidity and windy days. The Problem 2. More Structures in Fire Country Rural used to mean a few hundred people living in the hills, now it means a few thousand. According to fire experts, there are over 46 million homes representing a population of over 100 million living in high fire hazard areas within the U.S. Sixty percent of all new homes are being built in fire country. Twenty-five percent of California’s population are at risk of losing their homes—almost 10 million people. The Problem But, warming and growth are not all: Air Pollution: Both gaseous and particulate pollution impact native soils and plants and favor invasive plants that have changed historic patterns of fire. Altered Hydrology: Drawing down aquifers and dry season runoff have a profound impact in the foothills and riparian corridors. Suppression: Wildfires used to roam landscapes for weeks, if not months. Fires nowadays are immediately extinguished—and only get a foothold during severe fire weather. -

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Page 1 of 261

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Page 1 of 261 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Points No. Title Author Level 46456 Come Here, Tiger! Moran, Alex 0.3 0.5 EN 66246 Show and Tell Mayer, Mercer 0.3 0.5 EN 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol 0.3 0.5 41850 Clifford Makes a Friend Bridwell, Norman 0.4 0.5 EN 58042 I Can Read, Too: Book #9 Sargent, Dave/Pat 0.4 0.5 EN 66204 My Trip to the Zoo Mayer, Mercer 0.4 0.5 EN 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol 0.4 0.5 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 66200 Country Fair Mayer, Mercer 0.5 0.5 EN 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 49483 Down on the Farm Lascaro, Rita 0.5 0.5 EN 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol 0.5 0.5 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 31542 Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby 0.5 0.5 EN 35665 What Day Is It? Trimble, Patti 0.5 0.5 EN 66242 Beach Day Mayer, Mercer 0.6 0.5 EN 72887 Cat Who Barked, The Sargent, Dave 0.6 0.5 EN 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans 0.6 0.5 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. 0.6 0.5 9364 EN Funny Baby, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 72885 Little Big Cat Sargent, Dave 0.6 0.5 EN 9383 EN Magic Beans, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 3051 EN My Dog's the Best! Calmenson, Stephanie 0.6 0.5 9391 EN Three Bears, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9392 EN Three Goats, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9393 EN Three Little Pigs, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 https://c.na6.content.force.com/servlet/servlet.FileDownload?file=00P8000000BHUWr 2/ 22/ 2012 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice -

State of the Ark

SSTTAATTEE OOFF TTHHEE AARRKK Dedicated to rescuing, housing and adopting homeless animals Look! It’s a Bird! It’s a Plane! It’s SuperDaisy … able to leap farm fences in a single bound … Volunteers, please note: Daisy has recently taken to scaling the farm fences to try her paw at a game of Canine Frogger on Route 29. Very soon she will begin training with an invisible fence but we ask that volunteers PLEASE exercise extreme diligence while Daisy is out as she has even broken away from her cable run. And while the invisible fence training process is supposed to be fairly quick, it is Daisy and if any dog were ever going to figure a way around this, it’s going to be her. Please help us keep Daisy safe. Thanks. Adoption Statistics Through December 31, 2006, the Humane Society adopted out 278 animals into loving homes: 183 cats, 64 dogs, 5 rabbits, 23 guinea pigs, 1 horse, 1 hamster and 1 fish! In addition, we transferred 11 cats and 19 dogs to other facilities for adoption. A special thanks to all of our foster homes, home visit volunteers, socializers, outreach program volunteers and adoption placement volunteers. HELPING THE COMMUNITY Through December 2006, we provided financial assistance or supplies to the public for approximately 40 animals to receive the medical care or supplies they needed. As you know, the HSFC instituted a new feral TNR (Trap, Neuter & Return) program in late 2003. Through December, the feral outreach program trapped, neutered and released (TNR’d) approximately 148 cats and kittens. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Wednesday, March 18, 2009 2:36:33PM School: Churchland Academy Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 36573 EN Big Egg Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 9329 EN Oh No, Otis! Frankel, Julie LG 0.4 0.5 97 F 9333 EN Pet for Pat, A Snow, Pegeen LG 0.4 0.5 71 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 9305 EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Stevens, Philippa LG 0.5 0.5 100 F 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet LG 0.5 0.5 144 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 196 F 7282 EN Lucky Bear Phillips, Joan LG 0.5 0.5 150 F 31542 EN Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby LG 0.5 0.5 106 F 901618 EN Night Watch (SF Edition) Fear, Sharon LG 0.5 0.5 51 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 74854 EN Cooking with the Cat Worth, Bonnie LG 0.6 0.5 135 F 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans LG 0.6 0.5 74 F 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. -

Jazzy and Kaleidoscopic, Like Fall Leaves, with Personalities to Match

For the friends of the Independent Cat Society, a no-kill cat shelter Fall 2011, # 134 Jazzy and kaleidoscopic, like fall leaves, with personalities to match... othing says “cozy” quite like the sight of a charming calico cat curled up in a Ncomfy ball of color. Colorful and delightful, calico cats are beloved by cat lovers everywhere. Like torties and tabbies, calicos are not a breed but rather a color pattern, created by the combination of white, black, and orange. In the case of calicos, the whole is most definitely greater than the sum of the parts! The name “calico” comes from a cloth first imported to Britain from India in the 17th century. Calico fabric was and still is brightly colored and distinctively patterned just like the cats. In Japan, tri-colored cats are called mi-ke, meaning “triple fur,” and in Holland they are called lapjeskat, which is Dutch for “patches.” It should come as no surprise that the two most common names for a calico cat are “Callie” and “Patches,” but there are other names inspired by their coat that may suit one of these multi- hued beauties, such as Autumn, Calista, Dottie, Jewel, Kalie (as in “kaleidoscope,”) Rainbow, or Sunset, and many more. Our own Paulette Gonzalez has made a science out of naming calicos, coming up with some of the most outrageous names, like Fiesta, Confetti, Maddie and Sophie (a dilute calico) are ICS alumni, and great examples Spumoni, and Salsa! Regardless of what you of calico beauty, as well as sisterly love! choose to call your own example of living color, she still may or may not come when you call her. -

Uncanny Domesticity and the Woman of Shame in Jessica Hagedorn's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Chung Hsing University Institutional Repository Tamkang Review 43.1 (December 2012): R3-26.un through the Jungle 3 ■ Run through the Jungle: Uncanny Domesticity and the Woman of Shame in Jessica Hagedorn’s Dream Jungle* Shu-ching Chen National Chung Hsing University Abstract This paper investigates the uncanniness of the decolonizing projects con- ducted by the local and global agents in Jessica Hagedorn’s Dream Jungle to accentuate the spectral afterlife of imperialism that haunts the Asia-Pacific in the age of globalization. Linking the uncanniness of the jungle with the for- mation of the subjugated and subjectivized body of the Filipina, the paper argues that the uncanny projects of nation-building and failed attempts of decolonization mark the beginning of the impoverishment of the Philippines in the restructuring of global capitalism in the 1980s. The outcome of the impoverishment is especially acute for Filipinas, for they are the group that bears the brunt of the economic change in the Philippines. My reading of the text consists of two parts. In the first part I draw upon Amy Kaplan’s conceptualization of “manifest domesticity” and the Freudian concept of the uncanny to examine the Filipino male characters’ nation-building and domes- tic managements, as well as the neocolonial tendency that belies America’s Shu-ching Chen is Professor of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at National Chung Hsing University in Taiwan. She received her Ph.D. in English at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. -

God Is There, After

Copyright © 2019, Dr. Mamata Dey All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. Published in India by Prowess Publishing, YRK Towers, Thadikara Swamy Koil St, Alandur, Chennai, Tamil Nadu 600016 eISBN: 978-81-944495-7-7 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication 1 The supposedly haunted house stood large and looming in the distance, silhouetted against the pale moonlight. Facing the narrow road that led to the only high school in the village, the house, atop a hill, orcharded trees bearing flowers and fruits that withered up on the branches, being untouched by human hands for many years. The boundary wall was not too high, but no school boy ever dared to jump over it and enter the grounds for fear of ghosts. It was rumoured that a tramp who had slept in the verandah one stormy night was found dead the next morning with blood oozing out of his tightly closed lips. Fruit trees of almost every variety was there in the garden and while mangoes, jackfruits and litchis hung lusciously from the branches in summer, red and yellow berries in winter tantalized way-farers. If anyone made bold to scale the wall and enter, others dissuaded him with such vehemence that he had to drop the idea. -

A Rattle of Pebbles

A Rattle of Pebbles: The First World War Diaries of Two Canadian Airmen Brereton Greenhous Un crépitement de galets: Les journaux de deux aviateurs canadiens de la première guerre mondiale Cover The cover illustration reproduces a pen and ink sketch, “Personality Counts In The Air”, by Frederick Horsman Varley (1881-1969), a founding member of Canada’s Group of Seven. This sketch was one of a series drawn in 1917 for re- cruiting posters and advertisements issued by RFC Canada — The Royal Flying Corps training organization set up in Canada to provide pilots for the war in Europe. (Courtesy Canadian War Museum) Couverture L’illustration reproduite en couverture est une esquisse plume et encre intitulée “Personality Counts In The Air”, de Frederick Horsman Varley (1881-1969), un des membres fondateurs du Groupe des Sept du Canada. Elle fait partie d’une série de dessins préparés en 1917 pour la conception d’affiches et d’annonces visant le recrutement pour la RFC Canada, organisme du Royal Flying Corps créé, au Canada, pour l’entraînement de pilots devant servir en Europe. (Courtoisie de Musée de Guerre canadien) DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL DEFENCE MINISTÈRE DE LA DÉFENSE NATIONALE DIRECTORATE OF HISTORY SERVICE HISTORIQUE Monograph No. 4 Monographie No. 4 Monograph/Monographie No. 1: F.J. Hatch, Aerodrome of Democracy: Canada and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan 1939-1945 Le Canada, aérodrome de la démocratie: Le plan d’entraînement aérien du Commonwealth britannique 1939-1945 Monograph/Monographie No. 2: O.A. Cooke, The Canadian Military Experience 1867-1983: A Bibliography Bibliographie de la vie militaire au Canada 1867-1983 Monograph/Monographie No. -

The Jinx, the Imposter, and Re-Enacting the Digital Thriller in True Crime Documentaries

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 3-23-2017 "You want it all to happen now!": The inxJ , The Imposter, and Re-enacting the Digital Thriller in True Crime Documentaries Brett ichM ael Phillips University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Phillips, Brett ichM ael, ""You want it all to happen now!": The inxJ , The mposI ter, and Re-enacting the Digital Thriller in True Crime Documentaries" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6743 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “You want it all to happen now!”: The Jinx, The Imposter, and Re-enacting the Digital Thriller in True Crime Documentaries by Brett Phillips A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Amy Rust, Ph.D. Maria Cizmic, Ph.D. Andrew Berish, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 10, 2017 Keywords: True crime, Documentary, Digital, Thriller, Reenactment, Affect Copyright © 2017, Brett Phillips ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, thank you to Amy, Maria, and Andrew for not only helping me shape this thesis—with both tiny chisel and sledgehammer—but for guiding me through an entire discipline with kindness and understanding. -

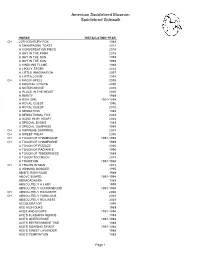

Saddlebred Sidewalk List 1989-2018

American Saddlebred Museum Saddlebred Sidewalk HORSE INSTALLATION YEAR CH 20TH CENTURY FOX 1989 A CHAMPAGNE TOAST 2011 A CONVERSATION PIECE 2014 A DAY IN THE PARK 2018 A DAY IN THE SUN 1999 A DAY IN THE SUN 1998 A KINDLING FLAME 1989 A LIKELY STORY 2014 A LITTLE IMAGINATION 2007 A LOTTA LOVIN' 1998 CH A MAGIC SPELL 2005 A MAGICAL CHOICE 2000 A NOTCH ABOVE 2016 A PLACE IN THE HEART 2000 A RARITY 1989 A RICH GIRL 1991-1994 A ROYAL QUEST 1996 A ROYAL QUEST 2010 A SENSATION 1989 A SENSATIONAL FOX 2002 A SONG IN MY HEART 2004 A SPECIAL EVENT 1989 A SPECIAL SURPRISE 1998 CH A SUPREME SURPRISE 2001 CH A SWEET TREAT 2000 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE 1991-1994 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE 1989 A TOUCH OF PIZZAZZ 2006 A TOUCH OF RADIANCE 1995 A TOUCH OF TENDERNESS 1989 A TOUCH TOO MUCH 2018 A TRADITION 1991-1994 CH A TRAVELIN' MAN 2012 A WINNING WONDER 1995 ABIE'S IRISH ROSE 1989 ABOVE BOARD 1991-1994 ABRACADABRA 1989 ABSOLUTELY A LADY 1999 ABSOLUTELY COURAGEOUS 1991-1994 CH ABSOLUTELY EXQUISITE 2005 CH ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS 2001 ABSOLUTELY NO LIMITS 2001 ACCELERATOR 1998 ACE HIGH DUKE 1989 ACES AND EIGHTS 1991-1994 ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS 1989 ACE'S QUEEN ROSE 1991-1994 ACE'S REFRESHMENT TIME 1989 ACE'S SOARING SPIRIIT 1991-1994 ACE'S SWEET LAVENDER 1989 ACE'S TEMPTATION 1989 Page 1 American Saddlebred Museum Saddlebred Sidewalk HORSE INSTALLATION YEAR ACTIVE SERVICE 1996 ADF STRICTLY CLASS 1989 ADMIRAL FOX 1996 ADMIRAL'S AVENGER 1991-1994 ADMIRAL'S BLACK FEATHER 1991-1994 ADMIRAL'S COMMAND 1989 CH ADMIRAL'S FLEET 1998 CH ADMIRAL'S MARK 1989 CH ADMIRAL'S MARK