Dramatic Exchanges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Rosena Hill Jackson Resume

ROSENA M. HILL JACKSON 941-350-8566 [email protected] www.RosenaHill.com BROADWAY/New York Carousel Nettie Jack O’Brien/Justin Peck Prince of Broadway swing Harold Prince/ Susan Stroman After Midnight Rosena Warren Carlyle/Daryl Waters/Wynton Marsalis Carousel Ensemble Avery Fisher Hall/PBS “Live at Lincoln Center” Cotton Club Parade Rosena Encores City Center Lost in the Stars Mrs. Mckenzie Encores Z City Center Come Fly Away Featured Vocalist Marriott Marqui Theatre/Twyla Tharp The Tin Pan Alley Rag Monisha/Miss Lee Roundabout Theatre Co./Stafford arima,dir Oscar Hammerstein II: The Song is You Soloist Carnegie Hall/New York Pops Color Purple Church Lady Broadway Theatre Spamalot Lady of the Lake/Standby Mike Nichols dir. Imaginary Friends Mrs. Stillman & others Jack O'Brien dir. Oklahoma Ellen Trevor Nunn mus dir./Susan Stroman chor. Riverdance on Broadway Amanzi Soloist Gershwin Theater Marie Christine Ozelia Graciela Daniele dir. Ragtime Sarah’s Friend u/s Frank Galati, Graciela Daniele/Ford’s Center REGIONAL The Toymaker Sarah NYMF/Lawrence Edelson,dir The World Goes Round Woman #1 Pittsburgh Public Theater/Marcia Milgrom Dodge,dir Ragtime Sarah White Plains Performing Arts Center Man of Lamancha Aldonza White Plains Performning Arts Center Baby Pam/s Papermill Playhouse Dreamgirls Michelle North Carolina Theater Ain’t Misbehavin’ Armelia Playhouse on the Green Imaginary Friends Smart women soloist Globe Theater 1001 Nights Sophie George Street Playhouse Mandela (with Avery Brooks) Winnie Steven Fisher dir./Crossroads Brief History -

The Morning Line

THE MORNING LINE DATE: Tuesday, June 7, 2016 FROM: Melissa Cohen, Michelle Farabaugh Emily Motill PAGES: 19, including this page C3 June 7, 2016 Broadway’s ‘The King and I’ to Close By Michael Paulson Lincoln Center Theater unexpectedly announced Sunday that it would close its production of “The King and I” this month. The sumptuous production, which opened in April of 2015, won the Tony Award for best musical revival last year, and had performed strongly at the box office for months. But its weekly grosses dropped after the departure of its Tony-winning star, Kelli O’Hara, in April. Lincoln Center, a nonprofit, said it would end the production on June 26, at which point it will have played 538 performances. A national tour is scheduled to begin in November. The show features music by Richard Rodgers and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. The revival is directed by Bartlett Sher. C3 June 7, 2016 No More ‘Groundhog Day’ for One Powerful Producer By Michael Paulson Scott Rudin, a prolific and powerful producer on Broadway and in Hollywood, has withdrawn from a much- anticipated project to adapt the popular movie “Groundhog Day” into a stage musical. The development is abrupt and unexpected, occurring just weeks before the show is scheduled to begin performances at the Old Vic Theater in London. “Groundhog Day” is collaboration between the songwriter Tim Minchin and the director Matthew Warchus, following their success with “Matilda the Musical.” The new musical is scheduled to run there from July 15 to Sept. 17, and had been scheduled to begin performances on Broadway next January; it is not clear how Mr. -

Drama Book Shop Became an Independent Store in 1923

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD I N P R O U D COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE PLAYERS, NEW YORK CITY THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION SALUTING A UNIQUE INSTITUTION ♦ Monday, November 26 Founded in 1917 by the Drama League, the Drama Book Shop became an independent store in 1923. Since 2001 it has been located on West 40th Street, where it provides a variety of services to the actors, directors, producers, and other theatre professionals who work both on and off Broadway. Many of its employees THE PLAYERS are young performers, and a number of them take part in 16 Gramercy Park South events at the Shop’s lovely black-box auditorium. In 2011 Manhattan the store was recognized by a Tony Award for Excellence RECEPTION 6:30, PANEL 7:00 in the Theatre . Not surprisingly, its beneficiaries (among them Admission Free playwrights Eric Bogosian, Moises Kaufman, Lin-Manuel Reservations Requested Miranda, Lynn Nottage, and Theresa Rebeck), have responded with alarm to reports that high rents may force the Shop to relocate or close. Sharing that concern, we joined The Players and such notables as actors Jim Dale, Jeffrey Hardy, and Peter Maloney, and writer Adam Gopnik to rally support for a cultural treasure. DAKIN MATTHEWS ♦ Monday, January 28 We look forward to a special evening with DAKIN MATTHEWS, a versatile artist who is now appearing in Aaron Sorkin’s acclaimed Broadway dramatization of To Kill a Mockingbird. In 2015 Dakin portrayed Churchill, opposite Helen Mirren’s Queen Elizabeth II, in the NATIONAL ARTS CLUB Broadway transfer of The Audience. -

Barrington Pheloung's Cv

BARRINGTON PHELOUNG’S CV 2004/05 FILMS SHOPGIRL Production Company: Hyde Park Entertainment Directed by: Anand Tucker Produced by: Jon Jashni, Ashok Amritraj & Steve Martin Written by: Steve Martin LITTLE FUGITIVE Production Company: Little Fugitive Directed by: Joanna Lipper Produced by: Joanna Lipper, Vince Maggio, Nicholas Paleologos & Fredrick Zollo Written by: Joanna Lipper A PREVIOUS ENGAGEMENT Production Company: Bucaneer Films Directed by: Joan Carr-Wiggin Produced by: Joan Carr-Wiggin , David Gordian & Damita Nikapota Written by: Joan Carr-Wiggin TELEVISION IMAGINE: SMOKING DIARIES Directed by: Margy Kinmonth Production Company: BBC THE WORLD OF NAT KING COLE Produced by: Kari Lia Production Company: Double Jab Productions 2002/03 FILMS TOUCHING WILD HORSES Production Company: Animal Tales Productions Inc. Directed by: Eleanore Lindo Produced by: Lewis B. Chesler, David M. Perlmutter, Frank Huebner, Rob Vaughan Written by: Murray McRae TELEVISION THE STRANGE TALE OF BARRY WHO Directed by: Margy Kinmonth Documentary on Barry Joule Produced by: Margy Kinmonth/Sam Organ Production Company: Darlowsmithson Productions For BBC4. MOVE TO LEARN Directed by: Sheila Liljeqvist Documentary for Video Produced by: Sheila Liljeqvist and Barbara Pheloung Australian documentary, children with learning difficulties. SHORTS ARDEEVAN Short Feature film made in the UK. Directed and Produced by: Jonathan Richardson NIGHT’S NOONTIME Short Feature film made in the Canada. Executive Producers: Richard Clifford & Amar Singh Produced by: Hanna Tower Directed -

PETER PAN Or the Boy Who Would Not Grow Up

PRESS RELEASE NORTH HIGH SCHOOL to present PETER PAN or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up The Appleton North High School Theatre Department will present the play PETER PAN or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up on May 16th through the 19th in the North High School Auditorium, 5000 North Ballard Road. This new version adapted from the original J.M. Barrie play and novel by Trevor Nunn and John Caird for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre of London enjoyed phenomenal success when first produced. The famous team known for their productions of THE LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF NICHOLAS NICKLEBY and the musical LES MISERABLES have painstakingly researched and restored Barrie’s original play. “. .a national masterpiece.”—London Times. This is the beloved story of Peter, Wendy, Michael, John, Capt. Hook, Smee, the lost boys, pirates, and the Indians, and of course, Tinker Bell, in their adventures in Never Land. However, for the first time, the play is here restored to Barrie’s original intentions. In the words of adaptor, John Caird: “ We were fascinated to discover that there was no one single document called PETER PAN. What we found was a tantalizing number of different versions, all of them containing some very agreeable surprises….We have made some significant alterations, the greatest of which is the introduction of a new character, the Storyteller, who is in fact the author himself.” North’s theatre director, Ron Parker, states, “This is a very different PETER PAN than the one most people are familiar with. It is neither the popular musical version nor the Disney animated recreation, but goes back to Barrie’s original play and novel. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

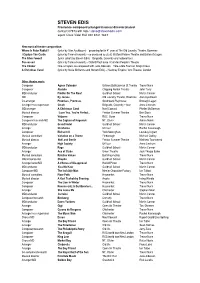

STEVEN EDIS Freelance Composer/Arranger/Musical Director/Pianist Contact 07973 691168 / [email protected] Agent Clare Vidal Hall 020 8741 7647

STEVEN EDIS Freelance composer/arranger/musical director/pianist contact 07973 691168 / [email protected] agent Clare Vidal Hall 020 8741 7647 New musical theatre composition: Where Is Peter Rabbit? (lyrics by Alan Ayckbourn) – preparing for its 4 th year at The Old Laundry Theatre, Bowness I Capture The Castle (lyrics by Teresa Howard) – co-produced by (& at) Watford Palace Theatre and Bolton Octagon The Silver Sword (lyrics (also!) by Steven Edis) – Belgrade, Coventry and national tour Possessed (lyrics by Teresa Howard) – Oxford Playhouse / Camden People's Theatre The Choker One-act opera co-composed with Jude Alderson – Tête-a-tête Festival. King's Cross A Christmas Carol (lyrics by Susie McKenna and Steven Edis) – Hackney Empire / Arts Theatre, London Other theatre work: Composer Agnes Colander Ustinov,Bath/Jermyn St Theatre Trevor Nunn Composer Aladdin Chipping Norton Theatre John Terry MD/conductor Fiddler On The Roof Guildhall School Martin Connor MD By Jeeves Old Laundry Theatre, Bowness Alan Ayckbourn Co-arranger Promises, Promises Southwark Playhouse Bronagh Lagan Arranger/mus.supervisor Crush Belgrade, Coventry + tour Anna Linstrum MD/arranger A Christmas Carol Noel Coward Phelim McDermott Musical director I Love You, You're Perfect... Frinton Summer Theatre Ben Stock Composer Volpone RSC, Swan Trevor Nunn Composer/research/MD The Captain of Köpenick NT, Olivier Adrain Noble MD/conductor Grand Hotel Guildhall School Martin Connor Arranger Oklahoma UK tour Rachel Kavanaugh Composer Richard III York/Nottingham Loveday Ingram -

Applause Magazine, Applause Building, 68 Long Acre, London WC2E 9JQ

1 GENE WIL Laughing all the way to the 23rd Making a difference LONDON'S THEATRE CRITI Are they going soft? PIUS SAVE £££ on your theatre tickets ,~~ 1~~EGm~ Gf1ll~ G~rick ~he ~ ~ e,London f F~[[ IIC~[I with ever~ full price ticket purchased ~t £23.50 Phone 0171-312 1991 9 771364 763009 Editor's Letter 'ThFl rul )U -; lmalid' was a phrase coined by the playwright and humourl:'t G eorge S. Kaufman to describe the ailing but always ~t:"o lh e m Broadway Theatre in the late 1930' s . " \\ . ;t" )ur ul\'n 'fabulous invalid' - the West End - seems in danger of 'e:' .m :: Lw er from lack of nourishmem, let' s hope that, like Broadway - presently in re . \ ,'1 'n - it too is resilient enough to make a comple te recovery and confound the r .: i " \\' ho accuse it of being an en vironmenta lly no-go area whose theatrical x ;'lrJ io n" refuse to stretch beyond tired reviva ls and boulevard bon-bons. I i, clUite true that the season just past has hardly been a vintage one. And while there is no question that the subsidised sector attracts new plays that, =5 'ears ago would a lmost certainly have found their way o nto Shaftes bury Avenue, l ere is, I am convinced, enough vitality and ingenuity left amo ng London's main -s tream producers to confirm that reports of the West End's te rminal dec line ;:m: greatly exaggerated. I have been a profeSSi onal reviewer long enough to appreciate the cyclical nature of the business. -

Rory Kinnear

RORY KINNEAR Film: Peterloo Henry Hunt Mike Leigh Peterloo Ltd Watership Down Cowslip Noam Murro 42 iBoy Ellman Adam Randall Wigwam Films Spectre Bill Tanner Sam Mendes EON Productions Trespass Against Us Loveage Adam Smith Potboiler Productions Man Up Sean Ben Palmer Big Talk Productions The Imitation Game Det Robert Nock Morten Tydlem Black Bear Pictures Cuban Fury Gary James Griffiths Big Talk Productions Limited Skyfall Bill Tanner Sam Mendes Eon Productions Broken* Bob Oswald Rufus Norris Cuba Pictures Wild Target Gerry Jonathan Lynne Magic Light Quantum Of Solace Bill Tanner Marc Forster Eon Productions Television: Guerrilla Ch Insp Nic Pence John Ridley & Sam Miller Showtime Quacks Robert Andy De Emmony Lucky Giant The Casual Vacancy Barry Fairbrother Jonny Campbell B B C Penny Dreadful (Three Series) Frankenstein's Creature Juan Antonio Bayona Neal Street Productions Lucan Lord Lucan Adrian Shergold I T V Studios Ltd Count Arthur Strong 1 + 2 Mike Graham Linehan Retort Southcliffe David Sean Durkin Southcliffe Ltd The Hollow Crown Richard Ii Various Neal Street Productions Loving Miss Hatto Young Barrington Coupe Aisling Walsh L M H Film Production Ltd Richard Ii Bolingbroke Rupert Goold Neal Street Productions Black Mirror; National Anthem Michael Callow Otto Bathurst Zeppotron Edwin Drood Reverend Crisparkle Diarmuid Lawrence B B C T V Drama Lennon Naked Brian Epstein Ed Coulthard Blast Films First Men Bedford Damon Thomas Can Do Productions Vexed Dan Matt Lipsey Touchpaper T V Cranford (two Series) Septimus Hanbury Simon Curtis B B C Beautiful People Ross David Kerr B B C The Thick Of It Ed Armando Iannucci B B C Waking The Dead James Fisher Dan Reed B B C Ashes To Ashes Jeremy Hulse Ben Bolt Kudos For The Bbc Minder Willoughby Carl Nielson Freemantle Steptoe & Sons Alan Simpson Michael Samuels B B C Plus One (pilot) Rob Black Simon Delaney Kudos Messiah V Stewart Dean Harry Bradbeer Great Meadow Rory Kinnear 1 Markham Froggatt & Irwin Limited Registered Office: Millar Court, 43 Station Road, Kenilworth, Warwickshire CV8 1JD Registered in England N0. -

Ull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater

Hull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater U DPR Papers of Alan Plater 1936-2012 Accession number: 1999/16, 2004/23, 2013/07, 2013/08, 2015/13 Biographical Background: Alan Frederick Plater was born in Jarrow in April 1935, the son of Herbert and Isabella Plater. He grew up in the Hull area, and was educated at Pickering Road Junior School and Kingston High School, Hull. He then studied architecture at King's College, Newcastle upon Tyne, becoming an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1959 (since lapsed). He worked for a short time in the profession, before becoming a full-time writer in 1960. His subsequent career has been extremely wide-ranging and remarkably successful, both in terms of his own original work, and his adaptations of literary works. He has written extensively for radio, television, films and the theatre, and for the daily and weekly press, including The Guardian, Punch, Listener, and New Statesman. His writing credits exceed 250 in number, and include: - Theatre: 'A Smashing Day'; 'Close the Coalhouse Door'; 'Trinity Tales'; 'The Fosdyke Saga' - Film: 'The Virgin and the Gypsy'; 'It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet'; 'Priest of Love' - Television: 'Z Cars'; 'The Beiderbecke Affair'; 'Barchester Chronicles'; 'The Fortunes of War'; 'A Very British Coup'; and, 'Campion' - Radio: 'Ted's Cathedral'; 'Tolpuddle'; 'The Journal of Vasilije Bogdanovic' - Books: 'The Beiderbecke Trilogy'; 'Misterioso'; 'Doggin' Around' He received numerous awards, most notably the BAFTA Writer's Award in 1988. He was made an Honorary D.Litt. of the University of Hull in 1985, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1985. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream”: a Director's Notebook Natasha Bunnell Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Institute for the Humanities Theses Institute for the Humanities Spring 2003 “A Midsummer Night's Dream”: A Director's Notebook Natasha Bunnell Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/humanities_etds Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Bunnell, Natasha. "“A Midsummer Night's Dream”: A Director's Notebook" (2003). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, Humanities, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/d8jv-a035 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/humanities_etds/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for the Humanities at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute for the Humanities Theses by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM: A DIRECTOR’S NOTEBOOK by Natasha Bunnell B. A. August 1997, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HUMANITIES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2003 Approved by: Christopher Hanna (Director) Erfime Hendrix (Mdmber) Jary Copyright © 2003 by Natasha Bunnell. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1414392 Copyright 2003 by Bunnell, Natasha All rights reserved. ® UMI UMI Microform 1414392 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O.