Teacher Motivation and the Use of Computer-Based Interactive Multimedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PBS Kids Resources: Age Levels and Educational Philosophy

PBS Kids Resources: Age Levels and Educational Philosophy Ages 4-8 yr. olds: ARTHUR's goal is to help foster an interest in reading and writing, and to encourage positive social skills. Only available in PBS LearningMedia — Ages 3-7 yr. olds: BTL is a lively, educational blend of phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, and other teaching methods for preschool, kindergarten, and first grade students. Several independent, scientifically-based read- ing research studies have shown that Between the Lions has a significant impact in in- Ages 2-5 yr. olds: "Make believe" is key to early childhood development. Ages 2-6 yr. olds: The series supports young children’s science learning by introducing sci- entific inquiry skills, teaching core science concepts and vocabulary, and preparing pre- schoolers for kindergarten and first grade science curriculum — all in whimsical style. Ages 3-7 yr. olds: Modeling of ten positive character traits that represent social and emo- tional challenges that children face and must master in the course of development. Ages 3-5 yr. olds: The goal of the series is to inspire children to explore science, engineer- ing, and math in the world around them. Ages 8-11 yr. olds: Every episode, game and activity is motivated by Cyber- chase characters and settings, and on a math concept centered on national standards. From tackling fractions in ancient Greece to using decimals to repair train tracks in Rail- road Repair, kids learn that math is everywhere and a useful tool for solving problems. Ages 2-4 yr. olds: This series, for a new generation of children, tells its engaging stories about the life of a preschooler using musical strategies grounded in Fred Rogers’ land- mark social-emotional curriculum. -

AETN Resource Guide for Child Care Professionals

AAEETTNN RReessoouurrccee GGuuiiddee ffoorr CChhiilldd CCaarree PPrrooffeessssiioonnaallss Broadcast Schedule PARENTING COUNTS RESOURCES A.M. HELP PARENTS 6:00 Between the Lions The resource-rich PARENTING 6:30 Maya & Miguel COUNTS project provides caregivers 7:00 Arthur and parents a variety of multi-level 7:30 Martha Speaks resources. Professional development 8:00 Curious George workshops presented by AETN provide a hands-on 8:30 Sid the Science Kid opportunity to explore and use the videos, lesson plans, 9:00 Super WHY! episode content and parent workshop formats. Once child 9:30 Clifford the Big Red Dog care providers are trained using the materials, they are able to 10:00 Sesame Street conduct effective parent workshops and provide useful 11:00 Dragon Tales handouts to parents and other caregivers. 11:30 WordWorld P.M. PARENTS AND CAREGIVERS 12:00 Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood CAN ASK THE EXPERTS 12:30 Big Comfy Couch The PBS online Expert Q&A gives 1:00 Reading Rainbow parents and caregivers the opportunity to 1:30 Between the Lions ask an expert in the field of early childhood 2:00 Caillou development for advice. The service includes information 2:30 Curious George about the expert, provides related links and gives information 3:00 Martha Speaks about other experts. Recent subjects include preparing 3:30 Wordgirl children for school, Internet safety and links to appropriate 4:00 Fetch with Ruff Ruffman PBS parent guides. The format is easy and friendly. To ask 4:30 Cyberchase the experts, visit http://www.pbs.org/parents/issuesadvice. STAY CURRENT WITH THE FREE STATIONBREAK NEWS FOR EDUCATORS AETN StationBreak News for Educators provides a unique (and free) resource for parents, child care professionals and other educators. -

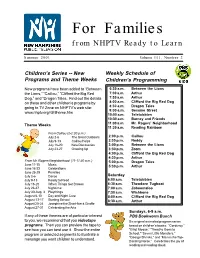

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn Summer 2001 Volume III, Number 2 Children’s Series -- New Weekly Schedule of Programs and Theme Weeks Children’s Programming New programs have been added to “Between 6:30 a.m. Between the Lions the Lions,” “Caillou,” “Clifford the Big Red 7:00 a.m. Arthur Dog,” and “Dragon Tales. Find out the details 7:30 a.m. Arthur on these and other children’s programs by 8:00 a.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog going to TV Zone on NHPTV’s web site: 8:30 a.m. Dragon Tales 9:00 a.m. Sesame Street www.nhptv.org/rtl/rtlhome.htm 10:00 a.m. Teletubbies 10:30 a.m. Barney and Friends Theme Weeks 11:00 a.m. Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood 11:30 a.m. Reading Rainbow From Caillou (2-2:30 p.m.) July 2-6 The Great Outdoors 2:00 p.m. Caillou July 9-13 Caillou Helps 2:30 p.m. Noddy July 16-20 New Discoveries 3:00 p.m. Between the Lions July 23-27 Growing Up 3:30 p.m. Zoom 4:00 p.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog 4:30 p.m. Arthur From Mr. Rogers Neighborhood (11-11:30 a.m.) 5:00 p.m. Dragon Tales June 11-15 Music 5:30 p.m. Arthur June 18-22 Celebrations June 25-29 Families July 2-6 Dance Saturday July 9-13 Ready to Read 6:00 a.m. Teletubbies July 16-20 When Things Get Broken 6:30 a.m. -

November (English)

Dennis-Yarmouth Title I From the Title I Coordinator Volume 1, Issue ii recommendations on books for you. ◊ Set aside time for reading. Designate a time November, 2017 of day when family members can read for pleasure. Make reading a part of your family routine. ◊Make reading special. Children should feel as if having a book is special. Help them create a space for storing their books. However, if your child doesn’t show an interest or strong ability in read- ing, be patient, but do not give up. Reading should be viewed as an enjoyable activity. ◊ Use your local library. One of the best resources you will have as a parent is access to your community’s library. It costs nothing to borrow books. Many libraries offer story hours and other fun literacy activities. Make visits to your library a routine activity. Yarmouth Libraries South Yarmouth—508-7600-4820 f you have any questions, please Parents play a specific role in their child’s literacy Yarmouthport—508-362-3717 contact me, Cookie Stewart, at 508- 778-7599 ext. 6204 or development by: creating a literacy-rich environ- West Yarmouth—508-775-5206 [email protected] ment; sharing reading and writing activities; acting Dennis Libraries as reading models; and demonstrating attitudes Jacob Sears—508-385-8151 toward education. A strong educational environ- Dennis Public Library—508-760-6219 ment at home can be a major factor in reinforcing the home-school connection. Limit television time. Monitior program selection Read to Your Child for your children. Discuss programs with them. -

The Relations of Parental Acculturation, Parental Mediation, and Children's Educational Television Program Viewing in Immigrant Families Yuting Zhao

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Relations of Parental Acculturation, Parental Mediation, and Children's Educational Television Program Viewing in Immigrant Families Yuting Zhao Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION THE RELATIONS OF PARENTAL ACCULTURATION, PARENTAL MEDIATION, AND CHILDREN’S EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION PROGRAM VIEWING IN IMMIGRANT FAMILIES By YUTING ZHAO A Thesis submitted to the Department of Educational Psychology and Learning Systems in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Yuting Zhao defended this thesis on December 7th, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Beth M. Phillips Professor Directing Thesis Alysia D. Roehrig Committee Member Yanyun Yang Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... vii -

The 35Th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy Award

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES 35th ANNUAL DAYTIME ENTERTAINMENT EMMY ® AWARD NOMINATIONS Daytime Emmy Awards To Be Telecast June 20, 2008 On ABC at 8:00 p.m. (ET) Live from Hollywood’s’ Kodak Theatre Regis Philbin to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York – April 30, 2008 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences today announced the nominees for the 35th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy ® Awards. The announcement was made live on ABC’s “The View”, hosted by Whoopi Goldberg, Joy Behar, Elisabeth Hasselbeck, and Sherri Shepherd. The nominations were presented by “All My Children” stars Rebecca Budig (Greenlee Smythe) and Cameron Mathison (Ryan Lavery), Farah Fath (Gigi Morasco) and John-Paul Lavoisier (Rex Balsam) of “One Life to Live,” Marcy Rylan (Lizzie Spaulding) from “Guiding Light” and Van Hansis (Luke Snyder) of “As the World Turns” and Bryan Dattilo (Lucas Horton) and Alison Sweeney (Sami DiMera) from “Days of our Lives.” Nominations were announced in the following categories: Outstanding Drama Series; Outstanding Lead Actor/Actress in a Drama Series; Outstanding Supporting Actor/Actress in a Drama Series; Outstanding Younger Actor/Actress in a Drama Series; Outstanding Talk Show – Informative; Outstanding Talk Show - Entertainment; and Outstanding Talk Show Host. As previously announced, this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award will be presented to Regis Philbin, host of “Live with Regis and Kelly.” Since Philbin first stepped in front of the camera more than 40 years ago, he has ambitiously tackled talk shows, game shows and almost anything else television could offer. Early on, Philbin took “A.M. Los Angeles” from the bottom of the ratings to number one through his 7 year tenure and was nationally known as Joey Bishop’s sidekick on “The Joey Bishop Show.” In 1983, he created “The Morning Show” for WABC in his native Manhattan. -

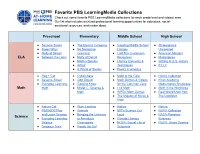

Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections Check out Some Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections for Each Grade Level and Subject Area

Favorite PBS LearningMedia Collections Check out some favorite PBS LearningMedia collections for each grade level and subject area. Our list also includes archived professional learning opportunities for educators, social- emotional resources, and maker ideas. Preschool Elementary Middle School High School ● Sesame Street ● The Electric Company ● Inspiring Middle School ● Shakespeare ● Super Why! ● No Nonsense Literacy Uncovered ● Molly of Denali Grammar ● LGBTQ+ Curriculum ● American Masters ELA ● Between the Lions ● Molly of Denali Resources ● Masterpiece ● Martha Speaks ● Literary Elements & ● Writing in U.S. History ● Arthur Techniques ● It’s Lit ● A World of Stories ● Poetry in America ● Peg + Cat ● Cyberchase ● Math at the Core ● NOVA Collection ● Sesame Street ● Odd Squad ● Math Games & Videos ● Khan Academy ● Everyday Learning: ● Good to Know for the Common Core Mathematics Showcase Math Math ● Mister C: Science & ● I <3 Math ● Math in the Workforce Math ● WPSU Math Games ● Real World Math from ● The Majesty of Music & The Lowdown Math ● Nature Cat ● Plum Landing ● Nature ● Nature ● PBS KIDS Play ● Animals ● MIT's Science Out ● NOVA Collection and Learn Science ● Bringing the Universe Loud ● NASA Planetary Science ● Everyday Learning: to America’s ● Climate Literacy Sciences Science Classrooms ● NOVA: Secret Life of ● NOVA: Gross Science ● Dinosaur Train ● Ready Jet Go! Scientists ● Let’s Go Luna ● All About the Holidays ● Teaching with Primary ● Access World Religions ● Xavier Riddle and ● NY State & Local Source Inquiry Kits -

Olson Medical Clinic Services Que Locura Noticiero Univ

TVetc_35 9/2/09 1:46 PM Page 6 SATURDAY ** PRIME TIME ** SEPTEMBER 5 TUESDAY ** AFTERNOON ** SEPTEMBER 8 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> The Lawrence Welk Show ‘‘When Guy Lombardo As Time Goes Keeping Up May to Last of the The Red Green Soundstage ‘‘Billy Idol’’ Rocker Austin City Limits ‘‘Foo Fighters’’ Globe Trekker Classic furniture in KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Barney & Friends The Berenstain Between the Lions Wishbone ‘‘Mixed Dragon Tales (S) Arthur (S) (EI) WordGirl ‘‘Mr. Big; The Electric Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase Nightly Business KUSD d V the Carnival Comes’’; ‘‘Baby and His Royal By Appearances December Summer Wine Show ‘‘Comrade Billy Idol performs his hits to a Grammy Award-winning group Foo Hong Kong; tribal handicrafts of the Street (S) (EI) (N) (S) (EI) Bears (S) (S) (EI) Breeds’’ (S) (EI) Book Ends’’ (S) (EI) Company (S) (EI) Ruffman (S) (EI) ‘‘Codename: Icky’’ Report (N) (S) Elephant Walk’’; ‘‘Tiger Rag.’’ Canadians (S) Harold’’ (S) packed house. (S) Fighters perform. (S) Makonde tribes. (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The Faith Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The King Is Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show (Season News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News News (N) (S) The Insider (N) Law & Order: Criminal Intent A Law & Order A firefighter and his Law & Order: Special Victims News (N) (S) Saturday Night Live Anne Hathaway; the Killers. -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Exploring the Vocabulary Teaching Strategies Used in Children's Educational Television

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Honors Projects Honors College Fall 12-11-2017 Exploring the Vocabulary Teaching Strategies Used in Children’s Educational Television Rebecca Wettstein [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Repository Citation Wettstein, Rebecca, "Exploring the Vocabulary Teaching Strategies Used in Children’s Educational Television" (2017). Honors Projects. 383. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects/383 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Running head: VOCABULARY IN EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION 1 Exploring the Vocabulary Teaching Strategies Used in Children’s Educational Television Rebecca C. Wettstein Bowling Green State University Submitted to the Honors College at Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with University Honors December 11, 2017 Dr. Virginia Dubasik, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Advisor Jeffrey Burkett, College of Education, Advisor VOCABULARY IN EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION 2 Abstract The present study explored the extent to which vocabulary instructional strategies are used in the children’s educational television show Word Girl, and whether or not the occurrences of vocabulary instructional strategies changed over the time the show was aired. Instructional strategies included repetition of target words, labeling, defining/mislabeling, and onscreen print. A total of eighteen episodes between 2007 and 2015 were analyzed. The early time period included episodes aired from 2007-2009, the middle time period included episodes aired from 2010-2012, and the late time period included episodes aired from 2013-2015. -

Get Wild About Reading! a Guide for Kindergarten Teachers from "Between the Lions." INSTITUTION WGBH-TV, Boston, MA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 446 856 PS 028 990 AUTHOR Cerier, Laura TITLE Get Wild about Reading! A Guide for Kindergarten Teachers from "Between the Lions." INSTITUTION WGBH-TV, Boston, MA. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC.; Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 37p.; A co-production of WGBH Boston and Sirius Thinking Ltd. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Beginning Reading; Childrens Television; Class Activities; *Emergent Literacy; Family School Relationship; Kindergarten; *Kindergarten Children; Learning Activities; Parent Materials; Parent School Relationship; Preschool Teachers; Primary Education; *Reading Instruction IDENTIFIERS Public Broadcasting ABSTRACT "Between the Lions" is a Public Broadcasting System program promoting literacy for children 4 through 7 years combining state-of-the-art puppetry, animation, live action, and music to achieve its mission of helping young children learn to read. This guide is designed to help kindergarten teachers integrate "Between the Lions" and its curriculum into their current classroom strategies. Organized around key topics in the series, the guide models the series' innovative whole-part-whole approach. The guide includes activities for the classroom, suggestions for particular episodes or segments to watch, separate take-home activities for families, recommended children's book titles, and related Web sites. The chapters are as follows: (1) "The ABCs of Between the Lions," an illustrated guide to the series, its characters, and its curriculum; (2) "Episode Descriptions"; (3) "Reading Aloud"; (4) "The Sounds of Words"; (5) "Print All Around Us"; (6) "Writing"; (7) "Using Technology"; (8) "Reading Milestones," basic guidelines on how reading ability develops; (9) "Marvelous Music," using music to teach language and reading skills; and (10) "Puppets," including characters to photocopy and cut out for classroom use.(KB) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Parentmatters

parPublishede by Thirteen/WNETnt Newm York’s Educationa Departmenttters summerSummer 20052004 Congratulations to our kids lineup Young Writers Weekdays AM and Illustrators! 6:30 Barney & Friends 7:00 Sesame Street ith hundreds of entries submitted 8:00 Cyberchase W for the local Reading Rainbow 8:30 Arthur Young Writers and Illustrators Contest, 9:00 Clifford The Big Red Dog 9:30 Dragon Tales the judges had a diffi cult task. In the end, 10:00 Postcards From Buster the work of four talented young people 10:30 Caillou stood out; the 2005 grand prize winners 11:00 Berenstain Bears are pictured here. 11:30 Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood Weekdays PM On May 7, the Brooklyn Public Library held 2:30 Reading Rainbow / Between The Lions KINDERGARTEN: their annual Reading Rainbow Celebration SECOND GRADE: Amin Mustefa, Eric Benjamin 3:00 Zoom I Wish I Was a Vampire to honor contest winners. First place Morgenstern, 3:30 Postcards From Buster stories were brought to life by Storyteller Adam’s Rock Band 4:00 Arthur 4:30 Maya & Miguel Tammy Hall. After the presentation of the 5:00 Cyberchase prizes, magician Darryl Barnes performed Sundays AM awe-inspiring tricks and, in the end, pulled 6:30 Barney & Friends a rabbit out of his hat! 7:00 George Shrinks 7:30 Clifford’s Puppy Days We would like to thank the Brooklyn Public 8:00 Thomas & Friends Library for coordinating and hosting this 8:30 Bob The Builder event and Staples Business Advantage for 9:00 Arthur FIRST GRADE: their generous donation of the prizes.