Introducing the Literature of the Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

MODERN BRITISH LITERATURE (C. 1900 to 1950) READING LIST

MODERN BRITISH LITERATURE (c. 1900 to 1950) READING LIST Please note that there are two lists below. The first is the full list with the core readings in bold; the second is the core list separated out. You are responsible for all core readings and may incorporate readings from the full list into your tailored list. Unless otherwise noted, selections separated by commas indicate all works students should know. A. FICTION Beckett, Samuel. One of the following: Murphy, Watt, Molloy Bennett, Arnold. Clayhanger Bowen, Elizabeth. The Heat of the Day Butler, Samuel. The Way of All Flesh Chesterton, G.K. The Man Who Was Thursday Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness AND one of: Lord Jim, The Secret Agent, Nostromo, Under Western Eyes Ford, Ford Madox. The Good Soldier Forster, E. M. Howards End, A Passage to India (plus the essays “What I Believe” and “The Challenge of Our Times” in Two Cheers for Democracy) Galsworthy, John. The Man of Property Greene, Graham. One of: Brighton Rock, The Power and the Glory, The Heart of the Matter Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World Joyce, James. Dubliners, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses Kipling, Rudyard. Kim Lawrence, D. H. Two of: Sons and Lovers, Women in Love, The Rainbow, The Plumed Serpent Lewis, Wyndham. Tarr, manifestos in BLAST 1 Mansfield, Katherine. “Prelude,” “At the Bay,” “The Garden Party,” “The Daughters of the Late Colonel” (in Collected Stories) Orwell, George. 1984 (or Aldous Huxley, Brave New World) Wells, H. G. One of the following: Ann Veronica, Tono-Bungay, The New Machiavelli West, Rebecca. -

Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2012 The nbU ought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N. Boggs Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boggs, Richard N., "The nbouU ght Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature" (2012). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 21. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/21 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Mentor: Dr. Thomas Cook Reader: Dr. Gail Sinclair Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature By Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Project Approved: ________________________________________ Mentor ________________________________________ Reader ________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Dedicated to my wife Elizabeth for her love, her patience and her unceasing support. CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Greek Pre-Chivalry 5 III. Roman Pre-Chivalry 11 IV. The Rise of Christian Chivalry 18 V. The Age of Chivalry 26 VI. -

Introduction to British Literature By: Patrick Mccann V 1.0 INTRODUCTION to BRITISH LITERATURE

Introduction to British Literature By: Patrick McCann v 1.0 INTRODUCTION TO BRITISH LITERATURE INSTRUCTIONS Welcome to your Continental Academy course “Introducti on to British Literature”. It is m ade up of 6 individual lessons, as listed in the Table of Contents. Each lesson includes practice questions with answers. You will progress through this course one lesson at a time, at your own pace. First, study the lesson thoroughly. Then, complete the lesson reviews at the end of the lesson and carefully che ck your answers. Sometimes, those answers will contain information that you will need on the graded lesson assignments. When you are ready, complete the 10-question, multiple choice lesson assignment. At the end of each lesson, you will find notes to help you prepare for the online assignments. All lesson assignments are open-book. Continue working on the lessons at your own pace until you have finished all lesson assignments for this course. When you have completed and passed all lesson assignments for this course, complete the End of Course Examination. If you need help understanding any part of the lesson, practice questions, or this procedure: Click on the “Send a Message” link on the left side of the home page Select “Academic Guidance” in the “To” field Type your question in the field provided Then, click on the “Send” button You will receive a response within ONE BUSINESS DAY 2 INTRODUCTION TO BRITISH LITERATURE About the Author… Mr. Patrick McCann taught English (Language and Literature) 9 through 12 for the past 13 years in the Prince Georges County (MD) school system. -

Widsith Beowulf. Beowulf Beowulf

CHAPTER 1 OLD ENGLISH LITERATURE The Old English language or Anglo-Saxon is the earliest form of English. The period is a long one and it is generally considered that Old English was spoken from about A.D. 600 to about 1100. Many of the poems of the period are pagan, in particular Widsith and Beowulf. The greatest English poem, Beowulf is the first English epic. The author of Beowulf is anonymous. It is a story of a brave young man Beowulf in 3182 lines. In this epic poem, Beowulf sails to Denmark with a band of warriors to save the King of Denmark, Hrothgar. Beowulf saves Danish King Hrothgar from a terrible monster called Grendel. The mother of Grendel who sought vengeance for the death of her son was also killed by Beowulf. Beowulf was rewarded and became King. After a prosperous reign of some forty years, Beowulf slays a dragon but in the fight he himself receives a mortal wound and dies. The poem concludes with the funeral ceremonies in honour of the dead hero. Though the poem Beowulf is little interesting to contemporary readers, it is a very important poem in the Old English period because it gives an interesting picture of the life and practices of old days. The difficulty encountered in reading Old English Literature lies in the fact that the language is very different from that of today. There was no rhyme in Old English poems. Instead they used alliteration. Besides Beowulf, there are many other Old English poems. Widsith, Genesis A, Genesis B, Exodus, The Wanderer, The Seafarer, Wife’s Lament, Husband’s Message, Christ and Satan, Daniel, Andreas, Guthlac, The Dream of the Rood, The Battle of Maldon etc. -

İED 142 (02) Classical Literature Instructor: Assist

Hacettepe University Faculty of Letters Department of English Language and Literature Course: İED 142 (02) Classical Literature Instructor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Taşdelen Year/Term: 2019-2020 Spring Class Hours: Monday 09:00-11:50 B2/203 Office Hours: Wednesday 10:00-12:00 Aim of the Course: This course intends to enable students to acquire a knowledge and appreciation of classical literature, through the study of the social and political life of Greece and Rome; and create awareness of a common European heritage deriving from the civilisations of Greece and Rome. It undertakes a brief survey of classical Greek and Roman literature with special emphasis on the epic and dramatic genres through the study of exemplary texts, which is essential for a better understanding and appreciation of not only British literature but also all Western literature and art. Course Content: In this course, ancient Greek and Roman civilisations are introduced to students within a social, cultural, historical, and literary context. Oral literary tradition, the epic tradition, Homeric epics, the birth and development of Classical Greek and Roman tragedy as well as comedy are dealt with in the light of representative literary texts. Course Outline: Week I: General introduction Brief history of ancient Greece General characteristics of Classical Greek literature The heroic ideal and heroic age Week II-VI: The epic tradition and the Homeric epics Homer The Iliad Week VII: Midterm I (06.04.2020) Week VIII: The birth, development, and features of Classical Greek tragedy Week IX: Greek tragedy Sophocles Oedipus the King Week X: The birth, development, and features of Roman tragedy Seneca Thyestes Week XI: Midterm II (04.05.2020) Week XII: The birth, development, and features of Classical Greek comedy Aristophanes Lysistrata Week XIII: The birth, development, and characteristics of Roman comedy Plautus Pot of Gold Week XIV: Bank Holiday *There may be changes to the course outline. -

Study Material for Ba English History of English Literature

STUDY MATERIAL FOR B.A ENGLISH HISTORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE - II SEMESTER - IV, ACADEMIC YEAR 2020 - 21 UNIT CONTENT PAGE NO I AGE OF JHONSON-EIGHTEENTH CENTURY PROSE 02 AGE OF WORDSWORTH- EARLY NINTEENTH CENTURY II 04 POETS (THE ROMANTICS) AGE OF TENNYSON- NINETEENTH CENTURY NOVELISTS III 05 (VICTORIAN NOVELISTS) IV AGE OF HARDY 07 V THE PRESENT AGE 09 Page 1 of 12 STUDY MATERIAL FOR B.A ENGLISH HISTORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE - II SEMESTER - IV, ACADEMIC YEAR 2020 - 21 UNIT - I EIGHTEENTH CENTURY PROSE DANIEL DEFOE (1659-1731) Daniel Defoe wrote in bulk. His greatest work is the novel Robinson Crusoe. It is based on an actual event which took place during his time. Robinson Crusoe is considered to be one of the most popular novels in English language. He started a journal named The Review. His A Journal of the Plague Year deals with the Plague in London in 1665. Sir Richard Steele and Joseph Addison worked together for many years. Richard Steele started the periodicals The Tatler, The Spectator, The Guardian, The English Man, and The Reader. Joseph Addison contributed in these periodicals and wrote columns. The imaginary character of Sir Roger de Coverley was very popular during the eighteenth century. Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) is one of the greatest satirists of English literature. His first noteworthy book was The Battle of the Books. A Tale of a Tub is a religious allegory like Bunyan‟s Pilgrim’s Progress. His longest and most famous work is Gulliver’s Travels. Another important work of Jonathan Swift is A Modest Proposal. -

Large Castles and Large War Machines In

Large castles and large war machines in Denmark and the Baltic around 1200: an early military revolution? Autor(es): Jensen, Kurt Villads Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/41536 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_30_11 Accessed : 5-Oct-2021 17:35:20 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Kurt Villads Jensen * Revista de Historia das Ideias Vol. 30 (2009) LARGE CASTLES AND LARGE WAR MACHINES IN DENMARK AND THE BALTIC AROUND 1200 - AN EARLY MILITARY REVOLUTION? In 1989, the first modern replica in Denmark of a medieval trebuchet was built on the open shore near the city of Nykobing Falster during the commemoration of the 700th anniversary of the granting of the city's charter, and archaeologists and interested amateurs began shooting stones out into the water of the sound between the islands of Lolland and Falster. -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Using Medieval Literature to Teach Introductory Composition in the Community College Setting David Vernon Martin Iowa State University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Repository @ Iowa State University Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2011 Using Medieval Literature to Teach Introductory Composition in the Community College Setting David Vernon Martin Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Martin, David Vernon, "Using Medieval Literature to Teach Introductory Composition in the Community College Setting" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12178. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Using medieval literature to teach introductory composition in the community college setting by David Martin A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee: Susan Yager, Major Professor Gloria Betcher Geoff Sauer Iowa State University Ames, IA 2011 Copyright © David Martin, 2011. All rights reserved. ii TABLE -

Introduction to Victorian and Twentieth-Century Literature Heesok Chang

Introduction to Victorian and Twentieth-Century Literature Heesok Chang Unlike the preceding three volumes in this Companion to British Literature – the Medieval, Early Modern, and Long Eighteenth Century – the current one attempts to cover at least two distinct periods: the Victorian and the Twentieth Century. To make matters more difficult, the second of these hardly counts as a single period; it is less an epoch than a placeholder. In terms of periodization, the Victorian era is succeeded – or some might say, overthrown – by the Modern. But modernism is not capacious enough to encompass the various kinds of literary art that emerged in Britain following World War II, the postmodern and the postcolonial, for example. We could follow the lead of recent scholars and expand the modernist period beyond the “high” to include the “late” and arguably the “post” as well. But this conceptual as well as temporal expansion does not take in the vital British literature written from the 1970s onward, an historical era distinct from the “postwar” that critics refer to, for now, as the “contemporary” (see English 2006). Of course, all periods are designated after they have finished, including the Victo- rian, which was very much a modernist creation. Yet it is unlikely we will come to call the period stretching from the middle of the last century to the early decades of the new millennium, from the breakup of Britain’s empire to the devolution of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, “Elizabethan.” And this despite the Victo- rian longevity of the Windsor monarch’s reign. The queen is one and the same, but the national culture is anything but. -

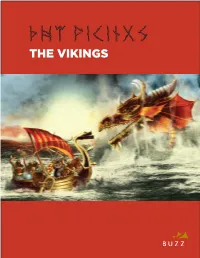

THE Vikings the VIKINGS

THE vikings THE VIKINGS 1 TABLE DES MATI RES TABLE OF CONTENTS Artistic Direction WHO WERE THE VIKINGS? Sylvain Lapointe Who were they? .............................................................................................. 4 Where did they come from? ...................................................................... ... 5 Text Pier-Luc Lasalle When did they live? .................................................................................... ... 5 Sailors ................................................................................................................ 6 Music Explorer-pirates and bandit-tradesmen ................................................ ... 7 Enrico O. Dastous How did one turn Viking? ......................................................................... ... 7 Mode of government ..................................................................................... 8 Staging Eloi ArchamBaudoin Trade ................................................................................................................. 8 Viking currency ............................................................................................... 9 Authorship of the Pedagogical Document Agriculture ....................................................................................................... 9 Aude Le Dubé DAILY LIFE IN THE VIKING ERA Translation Gaëtan Chénier Tasks ............................................................................................................. ... 10 Housing Cover Illustration Food