Perth Bands Were All the Rage, Man! Routes, Routines and Routes of Popular Music, Explored Through the End of Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Ade Papers

A GUIDE TO THE GEORGE ADE PAPERS PURDUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS © Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana Last Revised: July 26, 2007 Compiled By: Joanne Mendes, Archives Assistant TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) 1. Descriptive Summary……………………………………………….4 2. Restrictions on Access………………………………………………4 3. Related Materials……………………………………………………4-5 4. Subject Headings…………………………………………………….6 5. Biographical Sketch.......................………………………………….7-10 6. Scope and Content Note……….……………………………………11-13 7. Inventory of the Papers…………………………………………….14-100 Correspondence……...………….14-41 Newsletters……………………….....42 Collected Materials………42-43, 73, 99 Manuscripts……………………...43-67 Purdue University……………….67-68 Clippings………………………...68-71 Indiana Society of Chicago……...71-72 Scrapbooks and Diaries………….72-73 2 Artifacts…………………………..74 Photographic Materials………….74-100 Oversized Materials…………70, 71, 73 8. George Ade Addendum Collection ………………………………101-108 9. George Ade Filmography...............................................................109-112 3 Descriptive Summary Creator: Ade, George, 1866-1944 Title: The George Ade Papers Dates: 1878-1947 [bulk 1890s-1943] Abstract: Creative writings, correspondence, photographs, printed material, scrapbooks, and ephemera relating to the life and career of author and playwright George Ade Quantity: 30 cubic ft. Repository: Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries Acquisition: Gifts from George Ade, James Rathbun (George Ade's nephew by marriage and business manager), -

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

Media Release: Larrikin Puppets Launches Its Debut Song for Kids

Media Release: Larrikin Puppets Launches Its Debut Song For Kids MONDAY 30 MARCH, 2020: Popular Queensland children’s act Larrikin Puppets has released its debut song for kids ‘Dance Like A Unicorn’ with vocals by puppet monsters Scrambles and Marina. Well-established puppetry arts company Larrikin Puppets (Brett Hansen and Elissa Jenkins) perform colourful and exciting puppet shows and interactive puppetry workshops featuring zany characters and catchy songs. Highly entertaining and captivating, Larrikin Puppets’ fast-paced, feel-good puppetry celebrates fun, kindness and diversity while nurturing child development, encouraging audiences to talk, dance, sing and play along. Larrikin Puppets recorded four songs prior to lockdown and will be releasing them as singles in the coming months, with a view to completing their kids’ album by the end of 2020. Musician and Larrikin Puppets’ principal puppeteer Brett Hansen said he’s always valued the concept of not talking down to kids. “I was keen to create music for kids that featured simple lyrics, but didn’t talk down to them musically,” he said. “Already we’ve had a fan compare us to early ‘Tu-plang’ era Regurgitator which is a huge compliment for us as we recently performed puppets on stage and in the music video for Regurgitator Pogogo Show’s ‘Best Friends Forever’. Prior to running the successful puppetry arts company, Brett Hansen performed for 15 years in several Brisbane bands and played piano for improv theatre and kids theatre sports for six years. “It may seem strange for a puppet act to release songs for kids, but we are pretty renowned for doing things differently,” he said. -

Concert and Music Performances Ps48

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Collection CONCERT AND MUSIC PERFORMANCES PS48 This collection of posters is available to view at the State Library of Western Australia. To view items in this list, contact the State Library of Western Australia Search the State Library of Western Australia’s catalogue Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1975 April - September 1975 PS48/1975/1 Perth Concert Hall ABC 1975 Youth Concerts Various Reverse: artists 91 x 30 cm appearing and programme 1979 7 - 8 September 1979 PS48/1979/1 Perth Concert Hall NHK Symphony Orchestra The Symphony Orchestra of Presented by The 78 x 56 cm the Japan Broadcasting Japan Foundation and Corporation the Western Australia150th Anniversary Board in association with the Consulate-General of Japan, NHK and Hoso- Bunka Foundation. 1981 16 October 1981 PS48/1981/1 Octagon Theatre Best of Polish variety (in Paulos Raptis, Irena Santor, Three hours of 79 x 59 cm Polish) Karol Nicze, Tadeusz Ross. beautiful songs, music and humour 1989 31 December 1989 PS48/1989/1 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Elisa Wilson Embleton (soprano), John Kessey (tenor) Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1990 7, 20 April 1990 PS48/1990/1 Art Gallery and Fly Artists in Sound “from the Ros Bandt & Sasha EVOS New Music By Night greenhouse” Bodganowitsch series 31 December 1990 PS48/1990/2 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Emma Embleton Lyons & Lisa Brown (soprano), Anson Austin (tenor), Earl Reeve (compere) 2 November 1990 PS48/1990/3 Aquinas College Sounds of peace Nawang Khechog (Tibetan Tour of the 14th Dalai 42 x 30 cm Chapel bamboo flute & didjeridoo Lama player). -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Andrew Brassington | Managing Director [email protected] Mobile: 0408 445 562 | Direct: 03 6251 3118

JAKS Song list You Shook Me All Night Long - AC/DC Big Jet Plane - Angus & Julia Stone Breakout - Ash Grunwald Reckless - Australian Crawl Wake Me Up - Avicii Buses and Trains - Bachelor Girl All I Want Is You - Ball Park Music Pompeii - Bastille Songbird - Bernard Fanning Firestone - Beth All the Small Things - Blink 182 Closer to Free - Bodeans Drop the Game - Chet Faker Farewell Rocketship - Children Collide Clocks - Coldplay Low - Cracker Bad Moon Rising - Creedence Clearwater Revival Down on the Corner - Creedence Clearwater Revival Fall at Your Feet - Crowded House Don't Dream It's Over - Crowded House Breakfast at Tiffany's - Deep Blue Something April Sun In Cuba - Dragon Save Tonight - Eagle Eye Cherry Cool Kids - Echosmith Home - Edward Sharpe www.ient.com.au Andrew Brassington | Managing Director [email protected] Mobile: 0408 445 562 | Direct: 03 6251 3118 Times Like These - Foo Fighters Pumped Up Kicks - Foster the People Take Me Out - Franz Ferdinand Shimmer - Fuel Budapest - George Ezra Blame it on me - George Ezra Shotgun - George Ezra Somebody That I Used to Know - Gotye Time of Your Life - Green Day She - Green Day Just Ace - Grinspoon Ways to Go - Grouplove Bittersweet - Hoodoo Gurus Throw Your Arms Around Me - Hunters n Collectors Never Tear Us Apart - INXS Way Out West - James Blundell/James Reyne Are You Gonna Be My Girl - Jet The Middle - Jimmy Eat World Happy - Pharrell Williams Country Roads - John Denver R.O.C.K in the USA - John Mellancamp Love Me Again - John Newman Notion - Kings of Leon Dinosaur - Kisschasy -

DJ Playlist.Djp

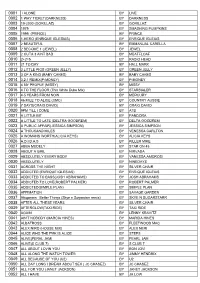

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

Newsletter Art Barn and Finch Lane Gallery ǀ Newsletter of the Salt Lake City Arts Council

SUMMER 2013 NEWSLETTER ART BARN AND FINCH LANE GALLERY ǀ NEWSLETTER OF THE SALT LAKE CITY ARTS COUNCIL TABLE OF CONTENTS 2013 TWILIGHT CONCERT SERIES Click title below to go directly to story. The Salt Lake City Arts Council is pleased to announce the 2013 Twilight Concert Series, now in its 26th season, returning to Pioneer Park with another tremendous Twilight Concert Series lineup. The series will run July 18 through September 5 every Thursday evening, with special back-to-back shows scheduled for Wednesday, August 7 and Thursday, Oelerich & Somsen Exhibition August 8. Featured performing artists include Belle & Sebastian, Blitzen Trapper, Public Art Program The Flaming Lips, The National, Sharon Van Etten, Grizzly Bear, Youth Lagoon, Erykah Badu, Kid Cudi, Empire of the Sun, and MGMT. Twilight concerts are a Wheatley & Ashcraft Exhibition longtime staple of Salt Lake City‘s downtown landscape, recognized for inviting Brown Bag Concert Series some of today‘s most impressive names in music to perform on summer nights, when the air is slightly cooler and where the community can come together under New Visual Arts Season a canopy of stars. City Arts Grants Deadlines For 2013, tickets are still just $5 for each concert and $35 for season tickets. Arts Council Welcomes New Season tickets are on sale now via the local ticketing agency, www.24tix.com. Staff Member Additionally, individual tickets will go on sale June 1 at noon and will be available online at 24tix.com and all Graywhale locations throughout the valley. Day of Lifelong Learning Class show entry will be allowed at the gate for $5. -

He Died with a Felafel Music Credits

(Cast) Melbourne University Choral Society Anna Cumming, Kim Asher, Anh-Dao Vlachos, Rachel Harris, Sarah Chan, Olivia March, Olivia Eckel, Michael Watts, Justin Presser, Arran Stewart, Benno Rice, Berin Boughton, Donald Shaw Music Editor & Soundtrack Producer Richard Lowenstein BestBoy Liaison Gary Seeger Music Supervision Mana Music Chris Gough Julie Spinks "Golden Brown" (Cornwell/Burnell/Greenfield/Black) Complete Music Limited/Festival Music Pty Ltd \EMI Music Publishing Performed by The Stranglers ℗ 1981 EMI Records Ltd Courtesy of EMI Music Australia "Buy Me A Pony" (Spiderbait) Sony/ATV Music Publishing Australia Performed by Spiderbait Courtesy of Grudge Records Under licence from Universal Music Australia "Run On" (Richard 'Moby' Hall) © 1999 Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp (BMI) & The Little Idiot Music (BMI) All rights on behalf of The Little Idiot Music (BMI) Administered by Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp (BMI) Performed by Moby Licensed from Festival Mushroom Group Courtesy of Mute Records & V2 "Ya Ya Ringe Ringe Raja" (Dorsey/Lewis/Levy) © 1961 EMI Longitude Music Co Licensed & Administered by EMI Music Publishing Australia Pty Ltd Performed by Goran Bregovic & Kolic Zlatko Courtesy of Mercury Records France Under licence from Universal Music Australia From the original soundtrack "Underground" "German Girl" (Bickford) Mushroom Music Publishing Performed by Paradise Motel Licensed from Festival Mushroom Group "Always On My Mind" (Christopher/James/Thompson) © 1971 Press Music Co/Screen Gems-EMI Music Inc/ © 1971 Budde -

New Shows Just Announced in Nsw for Summersalt with Two of Australia's

NEW SHOWS JUST ANNOUNCED IN NSW FOR SUMMERSALT WITH TWO OF AUSTRALIA’S FINEST… FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – FRIDAY 1ST DECEMBER, 2017: SummerSalt – the newly launched concert event continues to deliver cream of the crop artists to the great Australian outdoors as it announces two of Australia’s finest artists – John Butler Trio and Bernard Fanning as well as Mama Kin Spender & Oh Pep! SummerSalt takes place in some of the most picturesque locations around the country. On top of showcasing the best of home-grown and international bands, it also brings cultural attractions, placing a very heavy emphasis on local community and sustainability. This is a first of its kind. The inaugural SummerSalt series of concerts launched with some of Australia’s best loved bands & artists. With sun, salt air, and sweet music to wash over the Australian coast, SummerSalt will create the perfect setting to dance the afternoon away with your friends or chill on the beach. New South Wales audiences will be able to soak up some classic seaside charm under the spell of John Butler Trio, Bernard Fanning, Mama Kin Spender & Oh Pep! on the shores of Wollongong & Bondi Beach. John Butler remains one of the most successful independent artists in Australia’s history. His band, the John Butler Trio, have sold out a myriad of performances over the years in Australia and have gone on to take their music worldwide. John Butler has an impressive one million album sales to his name, has been the No. 1 most played artist on Australian radio and has numerous ARIA awards to write home about. -

FOLLOW AUSTRALIA TOUR 2014 Welcome to Sao Paulo ~ START SÃO PAULO Sao Paulo Is the Largest City in the Southern Today We Arrive Into Sao Paulo

Welcome to our 2014 FIFA World Cup Tour of Brazil & what a great city to start! WEDNESDAY 11 JUNE FOLLOW AUSTRALIA TOUR 2014 Welcome to Sao Paulo ~ START SÃO PAULO Sao Paulo is the largest city in the Southern Today we arrive into Sao Paulo. If you have Hemisphere, and with over 11 million purchased your flights through Fanatics, inhabitants it can be intimidating. The you will be met at the airport by a Fanatics financial and business hub of Brazil, the representative who will assist you with a locals claim it is a city where you can find transfer to your hotel. Those who booked everything! World class restaurants, fashion, their own flights to Brazil you will need to art and culture are all at your doorstep in make your own way to your designated tour this booming metropolis. hotel. Guarulhos Airport is approximately 30km from the city. A taxi fare will cost Our hotels are based all over Sao Paulo, R$100 but can be significantly more if the so take the time to explore the bars and traffic is bad. restaurants in the area around your hotel. We only have a short time here so get out & 7:00pm: Meet in the hotel lobby for a first make the most of it! night get together and a chance to meet your Fanatics Rep and fellow passengers. This may be in the hotel bar, or a local venue within walking distance of the hotel. Overnight: São Paulo THURSDAY 12 JUNE FIFA World Cup Kicks Off 9:00am - Meet your Fanatics rep in the hotel lobby ready for a massive day in Sao Paulo as the city becomes the focus of the world’s attention & plays host to the opening match of the 2014 World Cup, Brazil v Croatia! We depart our hotels at 9am and walk to the Metro station ready to board the train & head into the city centre together. -

Canada and Australia

CANADA AND AUSTRALIA: PROMOTING COLLABORATION IN CREATIVE INDUSTRIES Prepared by the Consulate General of Canada in Sydney 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Welcome & Introduction 4 Film & Television 11 Music 16 Literature 21 Performing Arts 25 Visual Arts 28 Digital Arts 30 Promoting Canadian Creators Globally 2 WELCOME & INTRODUCTION The creative industries represent an important part of In Australia, the demand in the creative industries Canada’s economy and exports however these times sector was booming pre-coronavirus and represented are unprecedented and present challenges never 6.2% of total Australian employment and employment. before seen for the sector. In light of current events, The creative industries were growing 40% faster than particularly the recent cancellations of cultural events, the Australian economy as a whole. Australia also the Consulate General of Sydney would like to reaffirm recognises the important role and positive impact of the government’s support for all the people affected, the arts in regional, rural and remote areas. This has directly or indirectly, by the coronavirus. We know that led to a growth in festivals, arts markets, concerts, 4 Film & Television times like these can be particularly difficult for self- performances and galleries expanding into these areas employed creative workers, community organizations, due to the positive impact on the community as well as and cultural organizations, among many others. the daily lives of Australians. 11 Music This report, written pre-coronavirus, may be a useful resource as the creative industries move from crisis to Canada and Australia share similar histories and values recovery and seek out new business opportunities.