Dream Sequences and Virtual Consummation in the Series Moonlighting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

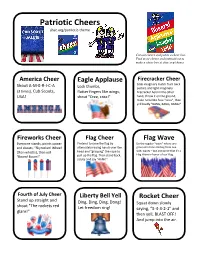

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

David Hume Kennerly Archive Creation Project

DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE CREATION PROJECT 50 YEARS BEHIND THE SCENES OF HISTORY The David Hume Kennerly Archive is an extraordinary collection of images, objects and recollections created and collected by a great American photographer, journalist, artist and historian documenting 50 years of United States and world history. The goal of the DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE CREATION PROJECT is to protect, organize and share its rare and historic objects – and to transform its half-century of images into a cutting-edge digital educational tool that is fully searchable and available to the public for research and artistic appreciation. 2 DAVID HUME KENNERLY Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist David Hume Kennerly has spent his career documenting the people and events that have defined the world. The last photographer hired by Life Magazine, he has also worked for Time, People, Newsweek, Paris Match, Der Spiegel, Politico, ABC, NBC, CNN and served as Chief White House Photographer for President Gerald R. Ford. Kennerly’s images convey a deep understanding of the forces shaping history and are a peerless repository of exclusive primary source records that will help educate future generations. His collection comprises a sweeping record of a half-century of history and culture – as if Margaret Bourke-White had continued her work through the present day. 3 HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE The David Hume Kennerly collection of photography, historic artifacts, letters and objects might be one of the largest and most historically significant private collections ever produced and collected by a single individual. Its 50-year span of images and objects tells the complete story of the baby boom generation. -

LAFF Program Schedule Listings in Eastern Time

LAFF Program Schedule Listings in Eastern Time Week Of 10-01-2018 LAFF 10/1 Mon 10/2 Tue 10/3 Wed 10/4 Thu 10/5 Fri 10/6 Sat 10/7 Sun LAFF 06:00A Movie: Dear God Movie: Double Take Movie: Funny About Love Movie: Milk Money Movie: Superstar Cybill: TV-PG D, L; CC Movie: All I Want For Christmas 06:00A 06:30A TV-PG L, V; 1996 TV-14 D, L, V; 2001 TV-14 D, S; 1990 TV-PG D, L, S, V; 1994 TV-14 D, L, V; 1999 Cybill: TV-PG D, L; CC TV-PG; 1991 06:30A 07:00A CC CC CC CC CC Cybill: TV-14 D, L; CC CC 07:00A 07:30A Cybill: TV-PG D, L; CC 07:30A 08:00A Grounded For Life: TV-PG D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, S; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L, S; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, S; CC Movie: Dear God 08:00A 08:30A Grounded For Life: TV-14 L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 L; CC TV-PG L, V; 1996 08:30A 09:00A Grounded For Life: TV-14 L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 L, S; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L; CC CC 09:00A 09:30A Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, S; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, S; CC 09:30A 10:00A Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC E/I: Jack Hanna's -

LIFF 2017 Honoree Dan Wooding His Career Must Rate As One of the Most Unusual in Journalism

HEALING THROUGH THE ART OF CINEMA LOVE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Liff.info Healing and Guiding Children Through Art The Lotus Light Children’s Charity | www.thelotuslight.org Love International Film Festival We are living in a world where chaos challenges every nation and every individual equally. Our mission is to live in a world where chaos challenges every nation and every individual equally. Fear of violence, hatred, persecution, misuse of religious and financial uncertainty follows us all. We stand divided in belief, nationalities and even within © countries-– ideology. We are a world that often seems bereft of hope or a unifying vision. It is our goal to turn the world’s eyes to the beauty that exist in front of us all. It is my hope that we will play a part in art and creativity returning everyone to the abundance that surrounds us all. When you look at our little planet from space, its singular beauty is clearly seen. Its smallness in the great void should communicate that we all live in one home. This world of ours is exactly that, it is a world of OURS; a place for all of us to share, build and nurture. Regardless of your religious beliefs, I hope you still believe in Love and Peace for all. Lets define God in his purest form as love and peace, and with this new definition, help each other and help build our home in a way that there is enough for all of us. This is the message of the festival, that through the power of creative energy and the efforts of filmmakers and artists alike, the world can become a unified and beautiful place. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

Movie Mirror Book

WHO’S WHO ON THE SCREEN Edited by C h a r l e s D o n a l d F o x AND M i l t o n L. S i l v e r Published by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., I n c . NEW YORK CITY t y v 3. 67 5 5 . ? i S.06 COPYRIGHT 1920 by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., Inc New York A ll rights reserved | o fit & Vi HA -■ y.t* 2iOi5^ aiblsa TO e host of motion picture “fans” the world ovi a prince among whom is Oswald Swinney Low sley, M. D. this volume is dedicated with high appreciation of their support of the world’s most popular amusement INTRODUCTION N compiling and editing this volume the editors did so feeling that their work would answer a popular demand. I Interest in biographies of stars of the screen has al ways been at high pitch, so, in offering these concise his tories the thought aimed at by the editors was not literary achievement, but only a desire to present to the Motion Picture Enthusiast a short but interesting resume of the careers of the screen’s most popular players, rather than a detailed story. It is the editors’ earnest hope that this volume, which is a forerunner of a series of motion picture publications, meets with the approval of the Motion Picture “ Fan” to whom it is dedicated. THE EDITORS “ The Maples” Greenwich, Conn., April, 1920. whole world is scene of PARAMOUNT ! PICTURES W ho's Who on the Screcti THE WHOLE WORLD IS SCENE OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES With motion picture productions becoming more masterful each year, with such superb productions as “The Copperhead, “Male and Female, Ireasure Island” and “ On With the Dance” being offered for screen presentation, the public is awakening to a desire to know more of where these and many other of the I ara- mount Pictures are made. -

And Neva Satterlee Mcnally Vaudeville Collection

Guide to the George E. "Mello" and Neva Satterlee McNally Vaudeville Collection NMAH.AC.0760 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2002 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Original Sheet Music................................................................................ 4 Series 2: Commercial Sheet Music.......................................................................... 5 Series 3: Photographs.............................................................................................. 7 Series 4: Memorabilia.............................................................................................. -

The Gang Dines Out” Season 8 Card 1

“THE GANG DINES OUT” SEASON 8 CARD 1 Watch Party Bingo! Look over your individual card, and when you see a moment happen or you hear one of the quotes listed below, mark the box on your card. First one to get five in a row - in any direction - calls B-I-N-G-O and wins your game! “PAY JACK KITCHEN DENNIS “WIND TRIBUTE” KNIFE DOOR HITS MAKES BENEATH TWIST DENNIS SPEECH MY WINGS” PILE WINE CHARLIE & THE GANG SOMEONE OF GLASSES FRANK TOAST CHEERS SAYS MATCHES CLINK TOGETHER “GUIGINO’S” WAITRESS SPAGHETTI WINE IS “COINCIDENCE” IS TIPPED FREE IS SPILLED POURED DENNIS SOMEONE CHARLIE & A/C GETS WAITER IS SINGS SAYS MAC MAKE TURNED UP TIPPED “CLASSY” EYE CONTACT DENNIS TIES COMPLAINS DEE SHOELACES DEE TAKES ARE ABOUT MOCKS TIED A SHOT WORN HIS CHAIR WAITER TOGETHER Bingo card not associated with any game, contest or sweepstakes. No prizing will be awarded. ©2020 FX “THE GANG DINES OUT” SEASON 8 CARD 2 Watch Party Bingo! Look over your individual card, and when you see a moment happen or you hear one of the quotes listed below, mark the box on your card. First one to get five in a row - in any direction - calls B-I-N-G-O and wins your game! WINE CHARLIE & SPAGHETTI DEE TAKES “COINCIDENCE” GLASSES MAC MAKE IS SPILLED A SHOT CLINK EYE CONTACT PILE OF SOMEONE CHARLIE & A/C GETS WAITER IS MATCHES SAYS FRANK TOAST TURNED UP TIPPED “CLASSY” DENNIS WAITRESS DENNIS WINE IS SINGS IS TIPPED FREE MAKES POURED SPEECH TIES JACK KITCHEN SHOELACES “WIND ARE KNIFE DOOR HITS TIED BENEATH WORN TWIST DENNIS TOGETHER MY WINGS” DENNIS “PAY COMPLAINS DEE ASKS THE GANG SOMEONE TRIBUTE” ABOUT SOMEONE CHEERS SAYS HIS CHAIR TO SIT TOGETHER “GUIGINO’S” Bingo card not associated with any game, contest or sweepstakes. -

Lecture Outlines

21L011 The Film Experience Professor David Thorburn Lecture 1 - Introduction I. What is Film? Chemistry Novelty Manufactured object Social formation II. Think Away iPods The novelty of movement Early films and early audiences III. The Fred Ott Principle IV. Three Phases of Media Evolution Imitation Technical Advance Maturity V. "And there was Charlie" - Film as a cultural form Reference: James Agee, A Death in the Family (1957) Lecture 2 - Keaton I. The Fred Ott Principle, continued The myth of technological determinism A paradox: capitalism and the movies II. The Great Train Robbery (1903) III. The Lonedale Operator (1911) Reference: Tom Gunning, "Systematizing the Electronic Message: Narrative Form, Gender and Modernity in 'The Lonedale Operator'." In American Cinema's Transitional Era, ed. Charlie Keil and Shelley Stamp. Univ. of California Press, 1994, pp. 15-50. IV. Buster Keaton Acrobat / actor Technician / director Metaphysician / artist V. The multiplicity principle: entertainment vs. art VI. The General (1927) "A culminating text" Structure The Keaton hero: steadfast, muddling The Keaton universe: contingency Lecture 3 - Chaplin 1 I. Movies before Chaplin II. Enter Chaplin III. Chaplin's career The multiplicity principle, continued IV. The Tramp as myth V. Chaplin's world - elemental themes Lecture 4 - Chaplin 2 I. Keaton vs. Chaplin II. Three passages Cops (1922) The Gold Rush (1925) City Lights (1931) III. Modern Times (1936) Context A culminating film The gamin Sound Structure Chaplin's complexity Lecture 5 - Film as a global and cultural form I. Film as a cultural form Global vs. national cinema American vs. European cinema High culture vs. Hollywood II. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

JERI BAKER Hair Stylist IATSE 706

JERI BAKER Hair Stylist IATSE 706 FILM FATALE Personal Hair Stylist to Hillary Swank Director: Deon Taylor ANT-MAN AND THE WASP Department Head Director: Peyton Reed Cast: Hannah John-Karmen, Paul Rudd, Judy Greer DEN OF THEIVES Department Head; Personal Hair Stylist to Gerard Butler Director: Christian Gudegast Cast: Gerard Butler, Dawn Olivieri SUBURBICON Personal Hair Stylist to Julianne Moore Director: George Clooney SPIDER-MAN: HOMECOMING Department Head Director: Jon Watts Cast: Tom Holland, Michael Keaton, Marisa Tomei, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jon Favreau, Laura Harrier, Tyne Daley KEEP WATCHING Department Head Director: Sean Carter Cast: Bella Thorne GHOST IN THE SHELL Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Director: Rupert Saunders CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Directors: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE WINTER Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson SOLDIER Directors: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo CHEF Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Director: Jon Favreau WISH I WAS HERE Department Head Director: Zach Braff Cast: Zach Braff, Kate Hudson, Ashley Greene, Josh Gad, Mandy Patinkin, Joey King DON JON Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Director: Joseph Gordon-Levitt THE MILTON AGENCY Jeri Baker 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 4 WE BOUGHT A ZOO Assistant Department Head Director: Cameron Crowe Cast: Thomas Haden Church, Elle Fanning BUTTER Assistant Department Head Director: Jim Field Smith Cast: Hugh Jackman, Alicia Silverstone, Ty Burrell SUPER 8 Assistant Department Head Director: J.J. Abrams Cast: Kyle Chandler, Jessica Tuck PEEP WORLD Department Head Director: Barry W.