Extending the Legacy Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2006

ANNUAL REPORT 2006 October 1, 2005 - September 30, 2006 NATIONAL CAPITAL PLANNING COMMISSION The National Capital Planning Commission is the federal government's central planning agency in the District of Columbia and surrounding counties in Maryland and Virginia. The Commission provides overall planning guidance for federal land and buildings in the National Capital Region. It also reviews the design of federal projects and memorials, oversees long-range planning for future development, and monitors capital investment by federal agencies. National Capital Planning Commission 401 9th Street, NW North Lobby, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20004 * Telephone 202.482.7200 Fax 202.482.7272 www.ncpc.gov U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Contents 1. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2 2. THE COMMISSION 4 3. SIGNATURE PLANNING INITIATIVES 6 4. URBAN DESIGN AND PLAN REVIEW 14 5. LONG-RANGE PLANNING 22 6. SHARING KNOWLEDGE LOCALLY AND GLOBALLY 24 7. ACHIEVEMENTS 26 8. FINANCIAL REPORT 27 9. THE YEAR AHEAD 28 *1 1Message from the Chairman and Executive Director Building a Framework for a and vibrant capital city while preserving the historic character of its treasured spaces. The Framework 21st Century Capital City Plan will provide a roadmap for improving the city's The National Capital Planning Commission forged a cultural landscape and visitor amenities. number of rewarding partnerships during Fiscal In collaboration with the District Department of Year 2006. Working closely with other federal and Transportation, NCPC began exploring ways to local agencies, we launched several major improve mobility in Washington by examining initiatives that we believe will benefit the national alternative routes for eight miles of rail lines that capital and all Americans. -

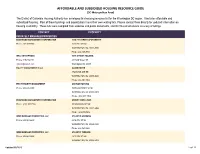

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

New York Avenue/Florida Avenue Charrette

CHARRETTE FALL 2006 National Capital Planning Commission e Florida A enue v v enue ork A New Y Eckington Plac eet O Street North Capitol Str ATF headquarters site eet t Str s Study Area Overview Fir Montgomery County Florida Avenue District of Columbia New York Avenue Prince George’s Arlington County County Fairfax County Alexandria City Capital Beltway Woodrow Wilson Bridge NATIONAL CAPITAL PLANNING COMMISSION NEW YORK AVENUE / FLORIDA AVENUE Charrette Executive Summary The National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), in partnership with the District Department of Transportation (DDOT), the General Services Administration (GSA), and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), initiated a charrette to study three potential long-term design alternatives for the intersection of New York and Florida Avenues. The District Department of Transportation developed the designs as part of its New York Avenue Corridor Study, completed in April 2006. Six independent consultants––with different areas of expertise such as urban design, engineering, traffic operation, economic development, and city planning––participated in the charrette, held from July 12 to July 14, 2006. The consultants were briefed extensively on relevant DDOT, NCPC, and District of Columbia Office of Planning (DCOP) studies, plans, and initiatives. They then interviewed 36 stakeholders from 24 different organizations to gather input from the community in the study area. Based on a review of the individual concepts, observations, and ideas expressed by the consultants during the charrette, NCPC and its partner agencies offer the following recommendations for the New York Avenue/Florida Avenue intersection and the New York Avenue corridor: 1. Regional through-traffic should be discouraged from using New York Avenue and encouraged to use alternative routes. -

The National Capital Urban Design and Security Plan

The National Capital Urban Design and Security Plan National Capital Planning Commission OCTOBER 2002 November2004Addendum The National Capital Urban Design and Security Plan is the result of close collaboration among the federal and District of Columbia governments, the professional planning and design community, security agencies, and civic, business, and community groups. The Interagency Security Task Force invited key public and private stakeholders to participate as members of its Core Advisory Group. During early development of the plan, National Capital Planning Commission staff presented its security design work to dozens of audiences in Washington and around the country. The plan was released in draft for public comment in July 2002. The Commission received dozens of responses from groups and individuals and carefully consid ered those comments in the preparation of this final plan. The National Capital Urban Design and Security Plan is available from the National Capital Planning Commission offices and is online at www.ncpc.gov. First Printing October 2002 Second Printing November 2004 The National Capital Planning Commission is the federal government’s planning agency in the District of Columbia and surrounding counties in Maryland and Virginia.The Commission provides overall planning guidance for federal land and buildings in the region. It also reviews the design of federal construction projects, oversees long-range planning for future develop ment, and monitors capital investment by federal agencies. National Capital Planning Commission 401 9th Street, NW North Lobby, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20576 Telephone | 202 482-7200 FAX | 202 482-7272 Web Site | www.ncpc.gov The National Capital Urban Design and Security Plan Illustration: Michael McCann National Capital Planning Commission OCTOBER 2002 MESSAGE FROM JOHN V. -

CCDC-Retail-Brochure-10.22.12.Pdf

Hines Retail Brochure/Folder Liska + Associates 650012 08.28.12 Revision 5 Hines Retail Brochure/Folder Liska + Associates 650012 08.28.12 Revision 5 9th Street & Palmer Alley — Condominiums above Hines Retail Brochure/Folder Liska + Associates 650012 09.25.12 Revision 11 A prominent location in the heart of the District puts CityCenterDC at the center of it all. Hines Retail Brochure/Folder Liska + Associates 650012 09.19.12 Revision 10 One Remarkable Place On a par with the greatest urban centers, CityCenterDC will be the District’s signature community. Located five blocks from the White House, this 10-acre development forms the core of a new mixed-use neighborhood, featuring residences, offices, public spaces, restaurants, a hotel and a critical mass of retail with unmatched offerings. CityCenterDC’s three city blocks offer a vibrant urban experience for residents, workers, shoppers and tourists and will quickly become the centerpiece of Downtown Washington, D.C. Hines Retail Brochure/Folder Liska + Associates 650012 09.21.12 Revision 9 Project Details SURROUNDING NEIGHBORHOODS PROJECT SCOPE Parcel Size 10-acres SHERIDAN- Retail 265,000 SQ FT KALORAMA Residential Rental 458 units W W W W W N NW NW N NW N NW N N T T T T T S ST S ST S S ST S ST Residential Condominiums 216 units H H H H H H T TH T T TH T 1 5T 2TH 1 5 10 8 7T 1 9 1 Office 515,000 SQ FT 18 W I M S O NW C Hotel 370 rooms R ON GEORGETOWN DUPONT CIRCLE LOGAN CIRCLE/SHAW S ST E S T W O ST NW O ST NE S I S N T N E N Total Parking 1,800 spaces 31 AV E AV E NW F L N O NEWPORT -

South Capitol Street Urban Design Study

South Capitol Street Urban Design Study The National Capital Planning Commission The District of Columbia Office of Planning January 2003 2 South Capitol Street Urban Design Study The National Capital Planning Commission The District of Columbia Office of Planning Chan Krieger & Associates Architecture & Urban Design Economic Research Associates (ERA) Economic Development January 2003 South Capitol Street Urban Design Study 1 2 Dear Friends and Colleagues: Great city streets are the very measure of urbanity. They are the stage for city life, the place of public contact, and the intersection where com- mercial enterprise and civic aspiration combine. The Champs Elysees in Paris, Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, and Unter den Linden in Berlin all demonstrate how cohesive and dynamic streets define and animate the life of their cities. South Capitol Street can be such a place. This one-mile stretch from the U.S. Capitol to a magnificent waterfront terminus on the Anacostia River has all the potential to rival the great urban boulevards of the world. With bold vision and creative leadership, South Capitol can be reborn as a vibrant city street for Washington residents and as a National Capital destination for all Americans. We envision the Corridor as a bustling mix of shops, offices, hotels, apartments, civic art, and open space. Where the street meets the river could be the site of a major civic feature such as a museum or memorial and offer additional attractions such as restau- rants, concerts, marinas and waterfront entertainment. This South Capitol Street and Urban Design Study was a cooperative effort between the District’s Office of Planning and the National Capital Planning Commission. -

Chapter 2 District-Wide Planning Page ______Planning Process

Chapter 2 District-wide Planning Page ________________________________________________________________________ Planning Process ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 39 Planning to the District’s Competitive Strengths .............................................................................................................................................................................. 43 A Green City ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 43 A Creative City.................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 45 An International City .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 46 A City of Public Places ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 47 A City of Distinctive Neighborhoods ................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Comprehensive Plan Central Washington Area Element

Comprehensive Plan Central Washington Area Element Proposed Amendments fDELETIONS ADDITIONS April 2020 Page 1 of 65 Comprehensive Plan Central Washington Area Element Proposed Amendments 1600 OVERVIEW Overview 1600 1600.1 The Central Washington Planning Area is the heart of Washington, DCthe DistriCt of Columbia. Its 6.8 square miles include the “mMonumental CCore” of the Districtcity, with such landmarks as the U.S. Capitol and White House, the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial, and the Federal Triangle and Smithsonian mMuseums. Central Washington also includes the cityDistrict’s traditional Ddowntown and other employment centers, such as the Near Southwest and East End. It includesAlso located there are Gallery PlaCe and Penn Quarter, the region’s entertainment and cultural center. Finally, Central Washington includes emergingmore recently densified urban neighborhoods like Mount Vernon Triangle and North of MassaChusetts Avenue (NoMaA). 1600.1 1600.2 The area’s boundaries are shown in the map of Central Washingtonat left. A majority of the area is within Ward 2, with portions also in Ward 6. All of Central Washington is within the boundaryBoundaries of L’Enfant’s 1791 plan for the City of Washington the 1791 L’Enfant Plan, and its the area’s streets, land uses, and design refleCt this legaCy. The area’s grand buildings, boulevards, and Celebrated open spaCes—partiCularly the monuments, museums, and federal buildings on the National Mall—define Washington, DC’s image as an international capital. Planning for this area is done collaboratively with the federal government, with and the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) having has land use authority over federal lands. -

Southwest Federal Center Heritage Trail ASSESSMENT REPORT

Southwest Federal Center Heritage Trail ASSESSMENT REPORT Showcasing Southwest Federal Center History and Culture National Capital Planning Commission | Cultural Tourism DC Table of Contents I. Execu ve Summary 1 Showcasing Federal and Southwest DC History and Culture ...........................2 Benefi ts to Local Businesses .............................................................................3 Capitalizing on the Momentum of Change ...................................................... 4 Purpose of the Heritage Trail Assessment Report ........................................... 6 II. Background 7 About Southwest Washington ..........................................................................8 About the District of Columbia Neighborhood Heritage Trails ........................9 III. Exis ng Condi ons 10 Study Area .......................................................................................................10 Land Use ......................................................................................................... 11 Cultural Resources in Federal Buildings ......................................................... 11 TransportaƟ on Infrastructure .........................................................................12 ExisƟ ng Street-Level/Pedestrian Experience ..................................................13 IV. Assessment Study Development 14 V. Possible Trail Route and Topics 15 Southwest Federal Center Heritage Trail DraŌ Outline ................................. 16 VI. Implementa on Timeline 18 -

National Mall Plan, Study Area

National Park Service enriching your U. S. Department of the Interior The National Mall Plan n the National Park Service celebrating the past, improving the present, The National Mall & Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Park Washington, D.C. d working to ensure a sustainable future r the National Mall. NORTH CAPITOLSTREET S www.nps.gov/nationalmallplan S I STREET MASSA 4th STREET 5th STREET Capital CHUSETTS AVENUE Children's Museum T H STREET H STREET T Government 2nd STREET Printing Office H STREET s N G STREET D UNIVERSITY NEW YO General Renwick PARK 50 50 P Accounting National O Galleryy T Martin Luther Office Postal O M King, Jr., Memorial G STREET Museum A 11th STREET Union Station C G STREET Library MCI G STREET E G STREET P ent American Art Museum Center A 24th STREET Executive National R of the (temporarily closed) 21st STREET K 19th STREET Building Thurgood 23rd STREET 18th STREET 22nd STREET Office National Portrait Gallery W y F STREET Building (temporarily closed) Museum Marshall A EETEET Y F STREET F STREET Judicial EAST EXECUTIVE PARK STR Ford's Theater National STR Building General THE th STREth STRE Law Enforcement VIRGINIA AVENUE Services National 13th STREET COLUMBUS WHITE 15t15t15t Officers Memorial Administration 17th STREET Historic Site MASSACHUSETTSMAS CIRCLE AVENUE SSACH A HOUSE PENNSYLVANIA AVE. NORTH E STREET JUDICIARY E STREET JOHN F. KENNEDY NEW YORKCorcoran AVE PPERSHINGERSH HUSET E STREET FREEDOM Federal SQUARE Gallery PARK District of TTS AV CENTER FOR THE Rawlins PLAZA Bureau of A Park of Art D.C. Court Columbia PERFORMING ARTS E STREET PENNSYLVANIA AVE. -

Comprehensive Plan Central Washington Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments Chapter 16 Public Review Draft Central Wash

Comprehensive Plan Central Washington Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments DELETIONS ADDITIONS CITATION HEADING CITATION Narrative Text. Citation NEW New text, policy, or action. CITATION Policy Element Abbreviation-Section Number. Policy Number: Policy Name CITATION Action Element Abbreviation-Section Number. Action Letter: Action Name Completed Action Text (at end of action and before citation): Completed – See Implementation Table. Chapter 16_Public_Review_Draft_Central Washington_Oct2019.docx Page 1 of 56 Comprehensive Plan Central Washington Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments Chapter 16_Public_Review_Draft_Central Washington_Oct2019.docx Page 2 of 56 Comprehensive Plan Central Washington Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments 1600 OVERVIEW 1600.1 The Central Washington Planning Area is the heart of the District of Columbia. Its 6.8 square miles include the “monumental core” of the city, with such landmarks as the U.S. Capitol and White House, the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial, and the Federal Triangle and Smithsonian Museums. Central Washington also includes the city’s traditional Downtown and other employment centers such as the Near Southwest and East End. It includes Gallery Place and Penn Quarter, the region’s entertainment and cultural center. Finally, Central Washington includes emerging more recently densified urban neighborhoods like Mount Vernon Triangle and North of Massachusetts Avenue (NoMaA). 1600.1 1600.2 The area’s boundaries are shown in the map at left. A majority of the area is within Ward 2, with portions also in Ward 6. All of Central Washington is within the boundary of the 1791 L’Enfant Plan and its streets, land uses, and design reflect this legacy. The area’s grand buildings, boulevards, and celebrated open spaces—particularly the monuments, museums, and federal buildings on the National Mall—define Washington’s image as an international capital.