A Biographical Study of Edward Baines with Special Reference to His Role As Editor, Author and Politician David

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haessly, Katie (2010) British Conservative Women Mps

British Conservative Women MPs and ‘Women’s Issues’ 1950-1979 Katie Haessly, BA MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2010 1 Abstract In the period 1950-1979, there were significant changes in legislation relating to women’s issues, specifically employment, marital and guardianship and abortion rights. This thesis explores the impact of Conservative female MPs on these changes as well as the changing roles of women within the party. In addition there is a discussion of the relationships between Conservative women and their colleagues which provides insights into the changes in gender roles which were occurring at this time. Following the introduction the next four chapters focus on the women themselves and the changes in the above mentioned women’s issues during the mid-twentieth century and the impact Conservative women MPs had on them. The changing Conservative attitudes are considered in the context of the wider changes in women’s roles in society in the period. Chapter six explores the relationship between women and men of the Conservative Parliamentary Party, as well as men’s impact on the selected women’s issues. These relationships were crucial to enhancing women’s roles within the party, as it is widely recognised that women would not have been able to attain high positions or affect the issues as they did without help from male colleagues. Finally, the female Labour MPs in the alteration of women’s issues is discussed in Chapter seven. Labour women’s relationships both with their party and with Conservative women are also examined. -

7-Night Southern Lake District Tread Lightly Guided Walking Holiday for Solos

7-Night Southern Lake District Tread Lightly Guided Walking Holiday for Solos Tour Style: Tread Lightly Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: CNSOS-7 2, 3 & 5 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW We are all well-versed in ‘leaving no trace’ but now we invite you to join us in taking it to the next level with our new Tread Lightly walks. We have pulled together a series of spectacular walks which do not use transport, reducing our carbon footprint while still exploring the best landscapes that the Southern Lake District have to offer. You will still enjoy the choice of three top-quality walks of different grades as well as the warm welcome of a HF country house, all with the added peace of mind that you are doing your part in protecting our incredible British countryside. Relax and admire magnificent mountain views from our Country House on the shores of Conistonwater. Walk in the footsteps of Wordsworth, Ruskin and Beatrix Potter, as you discover the places that stirred their imaginations. Enjoy the stunning mountain scenes with lakeside strolls or enjoy getting nose-to-nose with the high peaks as you explore their heights. Whatever your passion, you’ll be struck with awe as you explore this much-loved area of the Lake District. www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the South Lakes on foot • Choose a valley bottom stroll or reach for the summits on fell walks and horseshoe hikes • Let our experienced leaders bring classic routes and hidden gems to life • Visit charming Lakeland villages • A relaxed pace of discovery in a sociable group keen to get some fresh air in one of England’s most beautiful walking areas • Evenings in our country house where you can share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2, 3 and 5. -

Wakefield Amateur Rowing Club, 1846 – C.1876

‘Jolly Boating Weather…’ Wakefield Amateur Rowing Club, 1846 – c.1876 Nowadays rowing is typically viewed as a socially elite sport: that of grammar schools, universities and gentlemen. Whilst this is true to a point, historically rowing has cut across boundaries of class as much as any other sport. During the nineteenth century most sports, including rowing, were divided into three broad classes – working or tradesmen who made their living on the water as watermen or boatman; middle class and gentlemen amateurs; and those who made their living from the sport, who came from the working or middle class. This last group, the professional sportsmen rowers, were the equivalent of today’s superstars from football or rugby; the Clasper family or James Renforth from Newcastle had a massive following as true working class heroes who made a living from their prize money and boat-making skills. Harry Clasper (1812 to 1870) and his brothers were some of the first superstar sportsmen of their day and also the earliest professional sportsmen – in other words they were able to live from their winnings and what we would now term sponsorship. Rowing races and regattas were seen by the middle and gentry classes as a polite summer entertainment and also as the off-season equivalent of horse racing, with prizes and wagers commonly running into several hundreds of pounds. Regattas were established in London on the Thames before 1825 – the ‘Lambeth,’ ‘Blackfriars’ and ‘Tower’ regattas were held that summer with prizes being as high as £25.1 Most towns with access to a good stretch of water established Rowing Clubs, generally as an ‘out door amusement’ but increasingly during the nineteenth century for the ‘improvement of the working classes’ and ‘bringing out the bone and muscle of our English youth.. -

Issue 1 Spring 2013 in This Issue

TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall IIssssuuee 11 SSpprriinngg 22001133 IInn tthhiiss iissssuuee:: Ralph Cross The Forgotten First Battle of 1066 On Ilkley Moor Without A Hat Yorkshire Oatcakes The Bramhope Railway Tunnel The Arthington Viaduct with the 70013 speeding across before attacking the climb to Bramhope Tunnel It is has twenty semicircular arches spanning the Wharfe Valley and is unusual in that it is built along a curved path The Arthington Viaduct In Wharfedale 2 The Yorkshire Journal TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 1 Spring 2013 Left: Looking up Borough Beck with All Saints' Church in the far distance at Helmsley Cover: Ralph Cross on the North Yorkshire Moors Editorial his Spring issue marks the 3rd anniversary of The Yorkshire Journal. It is read by thousands of people throughout Britain and overseas, so with all the support and encouragement given to us by our readers, T we now continue into 2013. We all hope you enjoy reading more interesting stories and learning about places to visit. So with spring in the air we start off with an interesting visit to Ralph’s Cross on the North Yorkshire Moors. Then there is a fascinating story about the Battle at Fulford, near York, next we visit Ilkley Moor, the most famous moor in Yorkshire and this is followed by a story about Yorkshire Oatcakes. For our last feature we visit the remarkable Bramhope railway tunnel, which took 4 years to build at the cost of many lives. In the Spring issue: Yorkshire Oatcakes Ralph Cross By Sarah Harrison pages 18-21 By Jean Griffiths pages, 4-7 In the 1800s Yorkshire Oatcakes were very popular. -

Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team

EXPENDITURE OVER £500 - APRIL-JUNE 2016 Portfolio Division SupplierName ExpenditureDescription InternalReference Amount Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team Bevelo Ltd Printing & Stationery 1374115 1311 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team College of Policing Training 1369593 575 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371883 720 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1372592 3243.63 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1372591 720 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371936 3243.63 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371888 3243.63 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371886 3243.63 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1377567 3243.63 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371884 3243.63 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371935 720 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371882 3243.63 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371881 720 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371880 3243.63 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371879 720 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371885 720 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team CPOSA Insurance 1371887 720 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team PC World Business Office Equipment 1373826 778.01 Deputy Chief Constable Chief Officers Team PCC for Humberside Grants and Contributions -

The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata: Reports from Oceanic Exchanges

THE ATLAS OF DIGITISED NEWSPAPERS AND METADATA: REPORTS FROM OCEANIC EXCHANGES M. H. Beals and Emily Bell with additional contributions by Ryan Cordell, Paul Fyfe, Isabel Galina Russell, Tessa Hauswedell, Clemens Neudecker, Julianne Nyhan, Mila Oiva, Sebastian Padó, Miriam Peña Pimentel, Lara Rose, Hannu Salmi, Melissa Terras, and Lorella Viola and special thanks to Seth Cayley (Gale), Steven Claeyssens (KB), Huibert Crijns (KB), Nicola Frean (NLNZ), Julia Hickie (NLA), Jussi-Pekka Hakkarainen (NLF), Chris Houghton (Gale), Melanie Lovell-Smith (NLNZ), Minna Kaukonen (NLF), Luke McKernan (BL), Chris McPartlanda (NLA), Maaike Napolitano (KB), Tim Sherratt (University of Canberra) and Emerson Vandy (NLNZ) Document: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560059 Dataset: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560110 Disclaimer: This project was made possible by funding from Digging into Data, Round Four (HJ-253589). Although we have directly consulted with the various institutions discussed in this report, the final findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the discussed database providers or the contributors’ host institutions. Executive Summary Between 2017 and 2019, Oceanic Exchanges (http://www.oceanicexchanges.org), funded through the Transatlantic Partnership for Social Sciences and Humanities 2016 Digging into Data Challenge (https://diggingintodata.org), brought together leading efforts in computational periodicals research from six countries—Finland, Germany, Mexico, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States—to examine patterns of information flow across national and linguistic boundaries. Over the past thirty years, national libraries, universities and commercial publishers around the world have made available hundreds of millions of pages of historical newspapers through mass digitisation and currently release over one million new pages per month worldwide. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Authority and utility: John Millar, James Mill and the politics of history c.1770- 1836 Westerman, I. Publication date 1999 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Westerman, I. (1999). Authority and utility: John Millar, James Mill and the politics of history c.1770-1836. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:06 Oct 2021 The History of Authority CHAPTER FOUR 'THE COLD AND THANKLESS CLIMATE OF OPPOSITION' From May 1796 to August of the same year, Millar expressed his anxieties about the state of Britain in the light of the war with France in thirteen letters to the editor of the Scots Chronicle. The Scots Chronicle was an Edinburgh-based periodical that faced the harsh measures government took to dissuade the British populace from following the example set by the French. -

Register of Lords' Interests

REGISTER OF LORDS’ INTERESTS _________________ The following Members of the House of Lords have registered relevant interests under the code of conduct: ABERDARE, LORD Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director, F.C.M. Limited (recording rights) Category 10: Non-financial interests (c) Trustee, National Library of Wales (interest ceased 31 March 2021) Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Trustee, Stephen Dodgson Trust (promotes continued awareness/performance of works of composer Stephen Dodgson) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Sesquicentenary Committee (music) Director, UK Focused Ultrasound Foundation (charitable company limited by guarantee) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Society Trustee, West Wycombe Charitable Trust ADAMS OF CRAIGIELEA, BARONESS Nil No registrable interests ADDINGTON, LORD Category 1: Directorships Chairman, Microlink PC (UK) Ltd (computing and software) Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director and Trustee, The Atlas Foundation (registered charity; seeks to improve lives of disadvantaged people across the world) Category 10: Non-financial interests (d) President (formerly Vice President), British Dyslexia Association Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Vice President, UK Sports Association Vice President, Lakenham Hewitt Rugby Club (interest ceased 30 November 2020) ADEBOWALE, LORD Category 1: Directorships Director, Leadership in Mind Ltd (business activities; certain income from services provided personally by the member is or will be paid to this company; see category 4(a)) Director, Visionable -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

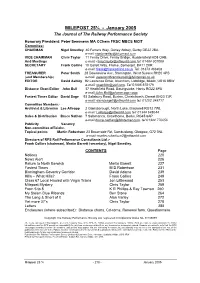

MILEPOST 25¾ - January 2005

MILEPOST 25¾ - January 2005 The Journal of The Railway Performance Society Honorary President: Peter Semmens MA CChem FRSC MBCS MCIT Commitee: CHAIRMAN Nigel Smedley 40 Ferrers Way, Darley Abbey, Derby DE22 2BA. e-mail: [email protected] VICE CHAIRMAN Chris Taylor 11 Fenay Drive, Fenay Bridge, Huddersfield HD8 OAB. And Meetings e-mail; [email protected] tel; 01484 307069 SECRETARY Frank Collins 10 Collett Way, Frome, Somerset, BA11 2XR e-mail: [email protected] Tel: 01373 466408 TREASURER Peter Smith 28 Downsview Ave, Storrington, West Sussex RH20 4PS (and Membership) e-mail: [email protected] EDITOR David Ashley 92 Lawrence Drive, Ickenham, Uxbridge, Middx, UB10 8RW e-mail: [email protected], Tel 01895 675178 Distance Chart Editor John Bull 37 Heathfield Road, Basingstoke, Hants RG22 4PA e-mail;[email protected] Fastest Times Editor David Sage 93 Salisbury Road, Burton, Christchurch, Dorset BH23 7JR e-mail: [email protected] tel; 01202 249717 Committee Members:- Archivist & Librarian Lee Allsopp 2 Gainsborough, North Lake, Bracknell RG12 7WL e-mail: [email protected] tel; 01344 648644 Sales & Distribution Bruce Nathan 7 Salamanca, Crowthorne, Berks, RG45 6AP e-mail [email protected], tel 01344 776656 Publicity Vacancy Non-committee officials:- Topical points Martin Robertson 23 Brownside Rd, Cambuslang, Glasgow, G72 0NL e-mail: [email protected] Directors of RPS Rail Performance Consultants Ltd.:- Frank Collins (chairman), Martin Barrett (secretary), -

Press Release 4 March 2021

PRESS RELEASE 4 MARCH 2021 Press release – Thursday 4 March Wetherspoon is to open beer gardens, roof top gardens and patios at 394 of its pubs in England from Monday April 12. The pubs will be open from 9am to 9pm (Sunday to Thursday inclusive) and 9am to 10pm (Friday and Saturday), although some have restrictions on closing times and in those cases will close earlier. They will offer a slightly reduced menu, to include breakfast, burgers, pizza, deli deals, fish and chips and British classics. Food will be available from 9am to 8pm seven days a week. Customers will be able to order and pay through the Wetherspoon app, however, Wetherspoon staff will be able to take orders and payment at the table from those who don’t have the app. The Wetherspoon pubs will not be operating a booking system. Customers will be able to enter the pub to gain access to the outside area and also to use the toilet. Test and trace will be in operation and hand sanitisers will be available. Wetherspoon chief executive John Hutson said: “We are looking forward to welcoming our customers and staff back to our pubs.” PUB LIST – UPDATED 30 MARCH 2021 The pubs below will be opening their outdoor County Durham areas on 12 April 2021. The Stanley Jefferson, Bishop Auckland The Wicket Gate, Chester-le-Street Please note that table-bookings are not taken The Company Row, Consett in any of our pubs. The Bishops’ Mill, Durham The Ward Jackson, Hartlepool Bedfordshire The Grand Electric Hall, Spennymoor The Pilgrim’s Progress, Bedford The Crown Hotel, Biggleswade Cumbria -

The Chartist Movement from Different Perspectives 9

Mill Waters Parks and Reservoir Education pack Social unrest and the law in Sutton in the 1800s SUPPORTED BY millwaters.org.uk Contents Welcome 1 Social unrest and the law in Sutton in the 1800s 2 Key Stage 1 Task 1: Discuss whether the actions of the Luddites were right or wrong 4 Task 2: Protest songs to promote the cause 5 Task 3: I predict a riot! 6 Key Stage 2 Task 1: Was the reaction to the Chartist uprisings over the top? 7 Task 2: Role play a Radical leader giving a rousing speech 8 Task 3: Write about the Chartist movement from different perspectives 9 Worksheets Worksheet 1: The Industrial Revolution in Sutton 10 Worksheet 2: Radical thinking 11 Worksheet 3: The Luddites 12 Worksheet 4: The Chartist Movement 16 Worksheet 5: Edward Unwin 18 Curriculum links 22 Welcome This education pack aims to help you get more out of your visit to Mill Waters Heritage Centre. It provides a selection of different We have included Teacher’s tips tasks for you to choose from. It to give a deeper understanding aims to make learning about the of an issue. We recognise the site’s history in relation to social skill of teachers in being able to unrest in the 1800s in a fun and tailor the activities to meet the engaging way. objectives of their visit and to suit pupils and ability. The time needed for each activity is an indication only and may There are also supplementary vary depending on the size of your historical resources, such as group and how fully you explore newspaper extracts, letters and various topics.