The Romance of the Swag

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elmore Leonard, 1925-2013

ELMORE LEONARD, 1925-2013 Elmore Leonard was born October 11, 1925 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Due to his father’s position working for General Motors, Leonard’s family moved numerous times during his childhood, before finally settling in Detroit, MI in 1934. Leonard went on to graduate high school in Detroit in 1943, and joined the Navy, serving in the legendary Seabees military construction unit in the Pacific theater of operations before returning home in 1946. Leonard then attended the University of Detroit, majoring in English and Philosophy. Plans to assist his father in running an auto dealership fell through on his father’s early death, and after graduating, Leonard took a job writing for an ad agency. He married (for the first of three times) in 1949. While working his day job in the advertising world, Leonard wrote constantly, submitting mainly western stories to the pulp and/or mens’ magazines, where he was establishing himself with a strong reputation. His stories also occasionally caught the eye of the entertainment industry and were often optioned for films or television adaptation. In 1961, Leonard attempted to concentrate on writing full-time, with only occasional free- lance ad work. With the western market drying up, Leonard broke into the mainstream suspense field with his first non-western novel, The Big Bounce in 1969. From that point on, his publishing success continued to increase – with both critical and fan response to his works helping his novels to appear on bestseller lists. His 1983 novel La Brava won the Edgar Award for best mystery novel of the year. -

*Indicative* Packing List Troopy for 3 People

*Indicative* Packing List Troopy for 3 People This is the list of included equipment and extras which are included in your rental. All equipment will need to be returned in good working order. If there is any breakage or if there are any items missing then we reserve the right to charge you the replacement value of the affected items. 1 Electric Roof Top Tent 1 Hammer 1 Maglite Torch 1 Solar Panel 2 Gas Bottle Holders 3 Headlights 1 Ladder 2 2kg Gas Bottles 1 Cigarette Lighter Splitter 3 Pillows + Covers 1 Cooker 1 Inverter 2 Comforters 1 Cooking Wind Screen 1 Air Compressor 2 Fitted Sheets 1 Drawer Table Inset 1 Set of Tyre Deflators 2 Sheets 1 Kettle 1 Air Hose and Gauge 2 Blankets 1 Drinking Water Hose 1 Wheel Nut Wrench 3 Beach Towels 4 Drawer Dividers 2 Complete Tool Sets 3 Bath Towels 1 Dustpan and Brush 1 PLB 1 Hand Towel 1 Bag of Laundry Pegs 3 High Visibility Jackets 2 Tea Towels 1 Clothesline 1 First Aid Kit 1 Awning 1 Solar Shower 2 Fire Extinguishers 6 Pegs 1 Engel Fridge Freezer 1 Spare/Extra Tent 1 Shovel 1 Esky 1 Table Swag 1 Plastic Box + Lid 4 Folding Chairs 1 One Person Mattress 2 Magnetic Flyscreens 3 Magnetic Curtains Sleeping Bag + Liner 1 Mobile Kitchen with: 4 Table Knives 4 Mugs 1 Peeler 4 Forks 4 Glasses 1 Pair of Scissors 4 Spoons 4 Dinner Plates 3 Wooden Spoons/Spatula 4 Short Teaspoons 4 Soup Bowls 3 Cooking Knives 4 Long Teaspoons 1 Colander 1 Dishwashing Bowl 1 Billy Teapot 1 Corkscrew/Bottle Opener 1 Spatula 1 Pot & Pan Set 1 Can Opener 1 Ladle 2 Pot Handles 1 Pair of Tongs 1 Salad Bowl 2 Cutting Boards 1 Tool Bag with: 1 Tyre Repair set 1 Box with Spare Fuses 2 One Litre Engine Oil 1 Jack 1 Pair of Gloves Other items: 2 Full Diesel Tanks 1 Bag with Maps and Books 3 Fly Hats 2 Full Water Tanks 1 Dishwashing Liquid 1 Outback Pack 1 Dish Washing Brush 1 Lighter / Sparker 1 Insect Repellent Baby / Booster Seat(s) 1 Spare Tent Key 1 WiFi Internet Router ➢ On return of the vehicle: Please fill both the Diesel Tanks and one Gas Bottle. -

OUTDOOR Sleeveless Shirts

Hard Slog Women’s ALLGOODS Sleeveless Shirts Lightweight, half button 100% cotton OUTDOOR sleeveless shirts. $ .95 Save 26 $10 CHRISTMAS Coast Highway Men’s Party Shirts Fun and bright party shirts, perfect for the festive season. Save $29 .95 up to SALE $10 5.11 Men’s Merrell Apex Shorts Save Men’s Features 2 way $ Ontario flex-tac mechanical 15 stretch fabric with Shoes zippered cargo Water repellent, all pockets. purpose travel shoe with Vibram sole. $ .95 $ Half 74 99 Price Merrell Women’s Oztrail 2 Person Siren Edge Q2 Dome Tent Easy to erect with mesh WP Shoes inner, fibreglass poles and a silver-coated Waterproof low fly. Perfect for music profile shoe for festivals. 205cm travel and off-road. x 150cm x 105cm and weights 1.9kgs. $ Save $ .95 Save 99 $90 44 $10 Everything for your summer adventures at Allgoods Buy it online! Visit allgoods.com.au ALLGOODS to purchase catalogue items online LAUNCESTON • DEVONPORT • HOBART allgoods.com.au SALE NOW ON, ENDS 17/12/19 Tasmanian owned and operated! ChristmasOUTDOOR SALE Thomas Thomas Cook R.M.Williams R.M.Williams Cook Women’s Men’s Women’s Men’s Classic Short 1932 Beverley Tailored Sleeve Polo Graphic Sleeveless Polo Tops Tops Save Tees Blouse Slightly Plain fashion $ Sleeveless blouse 15 Slim fit, with lace front slimmer than colours, rib cotton jersey traditional fit collar and cuffs inserts and lined signature with separate with rib collar Save and stretch for tees. and cuffs. $15 comfort. camisole. $ Save $ Save $ 49.95 $ 44.95 39 $10 10 9 $20 Thomas Thomas Cook R.M.Williams Cook Men’s Women’s Women’s Harry Spot Short Olivia Short Cotton Sleeve Shirts T-Shirts Sleeve Polo Tops Contrasting 100% cotton R.M.Williams Men’s trim on collar, jersey yarn-dyed Plain drill back & waist stripe polo with Save cotton collar Save Nicholson Shorts darts for a contrast patch with stretch for $ Stretch denim, regular fit shorts tailored fit. -

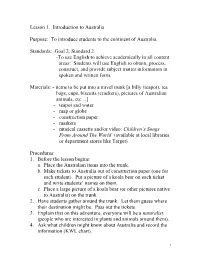

Lesson 1. Introduction to Australia Purpose: to Introduce Students To

Lesson 1. Introduction to Australia Purpose: To introduce students to the continent of Australia. Standards: Goal 2, Standard 2 -To use English to achieve academically in all content areas: Students will use English to obtain, process, construct, and provide subject matter information in spoken and written form. Materials: - items to be put into a travel trunk [a billy (teapot), tea bags, cups, biscuits (crackers), pictures of Australian animals, etc…] - teapot and water - map or globe - construction paper - markers - musical cassette and/or video: Children’s Songs From Around The World (available at local libraries or department stores like Target) Procedures: 1. Before the lesson begins: a. Place the Australian items into the trunk. b. Make tickets to Australia out of construction paper (one for each student). Put a picture of a koala bear on each ticket and write students’ names on them. c. Place a large picture of a koala bear (or other pictures native to Australia) on the trunk. 2. Have students gather around the trunk. Let them guess where their destination might be. Pass out the tickets. 3. Explain that on this adventure, everyone will be a naturalist, (people who are interested in plants and animals around them). 4. Ask what children might know about Australia and record the information (KWL chart). 1 5. Find Australia on a map or globe. a. Identify Australia as a continent b. Look at all the different landscapes (mountains, valleys, rivers). c. Discuss and describe the terms: city, bush, outback, Great Barrier Reef. 6. Examine the trunk. a. Display animal pictures. b. -

Australian Official Journal Of

Vol: 19 , No. 49 15 December 2005 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it at http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/ols/epublish/content/olsEpublications.jsp or using the "Online Journals" link on the IP Australia home page. The Australian Official Journal of Designs is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 15 December 2005 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes ...................... 15666 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed ................ 15668 Applications for Extension of Time ...................... 15666 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registartion/Protection .......... 15416 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1086850 to 1088113 ............................. 15399 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed ...................................... 15669 Withdrawn..................................... 15669 Assignments, Trasnmittals and Transfers .................. 15669 Cancellations of Entries in Register ...................... 15670 Corrigenda ...................................... 15671 Notices ........................................ 15666 Opposition Proceedings ............................. 15665 Removal/Cessation -

World Jambo Packing List (Scout) Daily Pack (SWAG Bag) Sunscreen

World Jambo Packing List (Scout) Daily Pack (SWAG Bag) NOTE: MARK EVERYTHING!!!!! Sunscreen Hat Water Bottle (water/sweatproof) Lighting System: Compass & Whistle Bug Spray (with Deet) Flashlight Stuff to Trade (patches, Pocket Knife Spare batteries (2 sets) neckers, etc) Raingear (coat or poncho) Glow stick Lip Balm (with sunscreen) First Aid kit (personal) Wet wipes Hand sanitizer Sunglasses Spare, dry socks Sleeping System Day of Service Sleeping Bag (3 Seasons) Work Gloves Sheet or Sleeping Bag Liner (recommended to cover up on warm nights) Bandana Knit cap (recommended to keep head warm on cool nights) Pillow (recommended) PUT LUGGAGE TAGS ON DUFFLE Footwear AND DAY PACK Hiking boots or good sneakers for hiking Aqua socks for water, optional Spare sneakers in case first pair gets wet Flip Flops for showers (recommended) Toiletries Toothbrush Small bottle liquid body wash Small wash cloth Toothpaste Deodorant “Shower” towel Small bottle of shampoo Brush/comb Clothing (clothing should be packed in gallon size or 3.5 gallon sized zip locked bags to stay clean and dry) Class A Boy Scout Field Uniform (shirt, pants, belt, US contingent neckerchief (friendship knot)) Notes: Bring hanger to hang in tent. Remove any/all pins and put in ziplock baggie so as not to lose World Jambo patch (right chest), US World Jambo patch (right pocket), Jambo Shoulder Patch OA Sash (packed for possible OA gathering/photo op) “Scout” T-shirts (wicking recommended) 5-6 “Scout” Pants 1-2 “Scout”Long Sleeved shirt (wicking recommended) 1-2 Underwear 5-6 pairs (wicking recommended) “Scout” Shorts 3-4 Spare Belts Swimwear Swimsuit Swim shirt Beach Towel (different than shower (optional/recommended) towel) Sleeping Clothes (Optional) Cooler weather clothing 2 pairs of pants. -

An Exploration of Member Involvement with Online Brand Communities (Obcs)

AN EXLORATION OF MEMBER INVOLVEMENT WITH ONLINE BRAND COMMUNITIES (OBCs) by Mary Loonam A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Marketing Birmingham Business School College of Social Sciences University of Birmingham October 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Despite growth in research investigating online consumer behaviour there appears to be a lack of study focusing specifically on how consumers are involved within online settings. Involvement is defined as the perceived relevance of a stimulus object such as a product to the individual consumer (Zaichkowsky, 1984). The study of consumer involvement is valuable as it is believed to be important mediator of consumer behaviour in the extant literature (e.g. Slater and Armstrong, 2010; Knox, Walker and Marshall, 1994). Involvement is thought to consist of two forms namely enduring involvement and situational involvement which respectively denote long-term and temporary interest in the stimulus object (Houston and Rothschild, 1978). Components such as personal interest, sign value, hedonic value and perceived risk have been conceptualised as evoking involvement (Kapferer and Laurent, 1993). -

Cambridge Companion Crime Fiction

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction covers British and American crime fiction from the eighteenth century to the end of the twentieth. As well as discussing the ‘detective’ fiction of writers like Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie and Raymond Chandler, it considers other kinds of fiction where crime plays a substantial part, such as the thriller and spy fiction. It also includes chapters on the treatment of crime in eighteenth-century literature, French and Victorian fiction, women and black detectives, crime in film and on TV, police fiction and postmodernist uses of the detective form. The collection, by an international team of established specialists, offers students invaluable reference material including a chronology and guides to further reading. The volume aims to ensure that its readers will be grounded in the history of crime fiction and its critical reception. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO CRIME FICTION MARTIN PRIESTMAN cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle:www.cambridge.org/9780521803991 © Cambridge University Press 2003 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the -

BERRIGAN SHOW 2019 PAVILION CLASSES PAVILION RULES and REGULATIONS CHIEF STEWARD in the PAVILION: Adele Schweicker 0439 722 386 PLEASE READ YOUR SCHEDULE CAREFULLY 1

BERRIGAN SHOW 2019 PAVILION CLASSES PAVILION RULES AND REGULATIONS CHIEF STEWARD IN THE PAVILION: Adele Schweicker 0439 722 386 PLEASE READ YOUR SCHEDULE CAREFULLY 1. All Exhibits are to be the absolute bona-fide work of, or grown by, the exhibitor named on the entry form. 2. Exhibits shall not bear any identifying mark of ownership. 3. Pavilion will be closed to the public during the judging of exhibits. 4. The Judges decision shall be final. 5. The Judge shall have the power to say if any exhibit be not worthy of a first prize. 6. Where there is only one (1) entry the judge may award a first prize if the exhibit is of sufficient merit. 7. The steward, under the direction, reserves the right to move an article from one class to another or from one section to another in the following - Class J Farm and Dairy Produce Section C, Class L Cooking, Section LA Junior Cooking, Class M – Jam and Preserves, Class N – Needlework, Section NA Junior Needlework, Berrigan A & H Society CWA Cup, Aged Care Facility Home Crafts, Class O - Cut Flowers, Class P – Education, Class Q – Arts, Class R – Crafts & Lego Class S – Scrapbooking, Class SJ – Jewellery & Beading and Class T – Photography. 8. No exhibits to be removed before 4.00 pm on show day, at which time exhibitors are to make contact with the relative stewards before removing exhibits. 9. The Society will take care of all exhibits but shall not be responsible for any accidental damage or loss of exhibits; nor for any exhibitors not collected. -

Henry Lawson - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Henry Lawson - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Henry Lawson(17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) Henry Lawson was an Australian writer and poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period and is often called Australia's "greatest writer". He was the son of the poet, publisher and feminist <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/louisa-lawson/">Louisa Lawson</a>. <b>Early Life</b> Henry Lawson was born in a town on the Grenfell goldfields of New South Wales. His father was Niels Herzberg Larsen, a Norwegian-born miner who went to sea at 21, arrived in Melbourne in 1855 to join the gold rush. Lawson's parents met at the goldfields of Pipeclay (now Eurunderee, New South Wales) Niels and Louisa married on 7 July 1866; he was 32 and she, 18. On Henry's birth, the family surname was anglicised and Niels became Peter Lawson. The newly- married couple were to have an unhappy marriage. Peter Larsen's grave (with headstone) is in the little private cemetery at Hartley Vale New South Wales a few minutes walk behind what was Collitt's Inn. Henry Lawson attended school at Eurunderee from 2 October 1876 but suffered an ear infection at around this time. It left him with partial deafness and by the age of fourteen he had lost his hearing entirely. He later attended a Catholic school at Mudgee, New South Wales around 8 km away; the master there, Mr. -

A Grammar of the Wirangu Language from the West Coast of South Australia

A grammar of the Wirangu language from the west coast of South Australia Hercus, L.A. A Grammar of the Wirangu Language from the West Coast of South Australia. C-150, xxii + 239 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-C150.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific,the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. -

L'tll'\. Thumbs on Ice Buzzer Revue Wichita State University

l'tll'\. Thumbs on Ice Buzzer Revue Wichita State University Round 10 1. They are formed during cell division when traces of the endoplasmic reticulum become caught in the new cell wall that divides the parent cell. These cytoplasmic canals between plant cell walls allow direct communication between plant cells. FTP name these gaps that allow intercellular coordination and unite plant cells in functioning tissues. Answer: plasmodesmata 2. He defeated the sons of Metion to claim his position as king of Athens. After sleeping with Aithra in Troezen the same night as Poseidon, he left a sword and a pair of sandals under a stone for the child to retrieve when he matured. He then returned to Athens and married Medea. FTP name this father of Theseus who threw himself into the sea from the Acropolis after Theseus forgot to spread white sails, which were to signify that he had survived his battle with the Minotaur. Answer: Aegeus 3. He was the commisioner of the American Soccer League from 1975-79. He also coached basketball at Boston College and for the Cincinatti Royals. It is as a basketball player, however, that he is most famous. He led the NBA in assists from 1953-60, and he ran the Celtics' offense in five championship seasons. FTP name this point guard named to the all-time NBA team in 1980. Answer: Bob Cousy 4. He's had as many books turned into movies as John Grisham, and has enjoyed the same success. So it would be surprising if you haven't heard of this author of popular crime novels, known for his use of local color and his realistic dialogue.