Kerby, Joseph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annexe CARTOGRAPHIQUE

S S R R R !" R $%&''()(* , R R - ! R - R - ". 0E -F 3R -, R (4- - '. 5 R R , , R 2 MM Le territoire du SAGE de l'Authie 1 Le Fliers L 'Au thie La Grouches ne en ili K L a La G é z a in c o u r to Entités géographiques Occupation du sol is e L'Authie et ses affluents Broussailles Limite du bassin hydrographique de l'Authie Bâti Pas-de-Calais Eau libre Somme Forêt Sable, gravier Zone d'activités 05 10 Km Masses d'eau et réseau hydrographique réseau et d'eau Masses Masse d'eau côtière et de transition CWSF5 transition de et côtière d'eau Masse Masse d'eau de surface continentale 05 continentale surface de d'eau Masse Masse d'eau souterraine 1009 : Craie de la vallée d vallée la de Craie : 1009 souterraine d'eau Masse L'Authie et ses affluents ses et L'Authie Le Fli ers e l'Authie e l Les masses d'eau concernant le territoire territoire le concernant d'eau masses Les ' A u t h i e du SAGE de l'Authie de SAGE du la Gézaincourtoise l a G r o u c h 0 10 l e a s K il ie n n 5 Km e 2 Les 156 communes du territoire du SAGE de l'Authie (arrêté préfectoral du 5 août 1999) et la répartition de la population 14 3 AIRON-NOTRE-DAME CAMPIGNEULLES-LES-GRANDES AIRON-SAINT-VAAST RANG-DU-FLIERS BERCK BOISJEAN WAILLY-BEAUCAMP VERTON CAMPAGNE-LES-HESDIN BUIRE-LE-SEC GROFFLIERS WABEN LEPINE GOUY-SAINT-ANDRE ROUSSENT CONCHIL-LE-TEMPLE MAINTENAY SAINT-REMY-AU-BOIS NEMPONT-SAINT-FIRMIN TIGNY-NOYELLE SAULCHOY CAPELLE-LES-HESDIN -

Mairie De DOULLENS

Transports Scolaires - année 2011/2012 DOULLENS Page 1/51 Horaires valables au mardi 30 août 2011 Transports Scolaires - année 2011/2012 ECOLE PUBLIQUE ETIENNE MARCHAND (DOULLENS) Ligne: 4-02-106 - Syndicat scolaire: BERNAVILLOIS (C.C.) - Sens: Aller - Transporteur: SOCIETE CAP Fréquence Commune Arrêt Horaire Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BERNAVILLE COLLEGE DU BOIS L'EAU 08:15 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BERNAVILLE PHARMACIE 08:18 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve FIENVILLERS ECOLE 08:25 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve CANDAS RUE DE DOULLENS 08:30 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS ECOLE ETIENNE MARCHAND 08:39 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS COLLEGE JEAN ROSTAND 08:40 Ligne: 4-03-106 - Syndicat scolaire: DOULLENNAIS (C.C.) - Sens: Aller - Transporteur: SOCIETE CAP Fréquence Commune Arrêt Horaire Lu-Ma-Je-Ve OCCOCHES ABRI 08:03 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve OUTREBOIS CENTRE 08:06 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve OUTREBOIS RUE DU HAUT 08:07 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve MEZEROLLES MONUMENT AUX MORTS 08:12 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve REMAISNIL ABRI R.D. 128 08:15 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BARLY PLACE 08:20 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve NEUVILLETTE PLACE 08:25 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BOUQUEMAISON PLACE 08:30 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS RANSART 08:35 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS HAUTE VISEE 08:40 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS ECOLE ETIENNE MARCHAND 08:45 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS COLLEGE JEAN ROSTAND 08:50 Ligne: 4-03-118 - Syndicat scolaire: DOULLENNAIS (C.C.) - Sens: Aller - Transporteur: SOCIETE CAP Fréquence Commune Arrêt Horaire Lu-Ma-Je-Ve HEM-HARDINVAL CENTRE 07:58 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve LONGUEVILLETTE CENTRE 08:14 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BEAUVAL RUE DE CREQUI 08:27 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BEAUVAL ECOLE PRIMAIRE 08:29 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BEAUVAL BELLEVUE 08:31 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve GEZAINCOURT BAGNEUX 08:39 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve GEZAINCOURT -

Cahier Des Charges De La Garde Ambulanciere

CAHIER DES CHARGES DE LA GARDE AMBULANCIERE DEPARTEMENT DE LA SOMME Document de travail SOMMAIRE PREAMBULE ............................................................................................................................. 2 ARTICLE 1 : LES PRINCIPES DE LA GARDE ......................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 2 : LA SECTORISATION ........................................................................................... 4 2.1. Les secteurs de garde ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Les lignes de garde affectées aux secteurs de garde .................................................... 4 2.3. Les locaux de garde ........................................................................................................ 5 ARTICLE 3 : L’ORGANISATION DE LA GARDE ...................................................................... 5 3.1. Elaboration du tableau de garde semestriel ................................................................... 5 3.2. Principe de permutation de garde ................................................................................... 6 3.3. Recours à la garde d’un autre secteur ............................................................................ 6 ARTICLE 4 : LES VEHICULES AFFECTES A LA GARDE....................................................... 7 ARTICLE 5 : L'EQUIPAGE AMBULANCIER ............................................................................. 7 5.1 L’équipage ....................................................................................................................... -

Fonds De L'école Publique D'autheux

DÉPARTEMENT DE LA SOMME CONSEIL DÉPARTEMENTAL ARCHIVES DÉPARTEMENTALES ÉCOLE PUBLIQUE D’AUTHEUX (1940-1973) Répertoire numérique détaillé 194 W établi par Morgan MAZURIER, archiviste sous la direction d’Élise BOURGEOIS, directrice adjointe et responsable du Service Aide aux Administrations Amiens, 2019-2020 1 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION Page 3 PRÉSENTATION DU FONDS Page 4 BIBLIOGRAPHIE Page 10 SOURCES COMPLÉMENTAIRES Page 12 PLAN DE CLASSEMENT Page 13 RÉPERTOIRE NUMÉRIQUE DÉTAILLÉ Page 14 2 INTRODUCTION Le 17 novembre 2017, un versement d’archives communales a été effectué. Lors du versement de ces archives, il est apparu que quelques documents (des cahiers d’appel journalier, des registres matricules et un journal de classe) appartenaient au fonds de l’école communale d’Autheux. Afin de respecter le cadre de classement des Archives départementales, chaque service producteur doit faire l’objet d’un versement distinct. Les documents issus de la commune ont été coté en E_DEP, quant aux documents du fonds de l’école, ils ont été cotés en 194W. Étant donné que le maire de la commune d’Autheux ne peut se substituer au directeur de l’école fermée dans les années 1970, il n’a pu être établi de bordereau de versement. Le fonds est donc considéré comme un fonds revendiqué par les Archives départementales compte-tenu du fait qu’il s’agit d’archives publiques. L’importance matérielle du versement est de 0,07 mètre linéaire, correspondant à 1 boîte. Après tri, élimination des doublons, il compte désormais 44 articles. Le versement s’étend de 1940 à 1973. 3 PRÉSENTATION DU FONDS LA COMMUNE D’AUTHEUX La commune d’Autheux est située dans le département de la Somme, dans l’arrondissement d’Amiens, et dans le canton de Doullens. -

SIEA Du Bernavillois (Siren : 200049641)

Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 SIAEP du Bernavillois (Siren : 200049641) FICHE SIGNALETIQUE BANATIC Données générales Nature juridique Syndicat intercommunal à vocation unique (SIVU) Syndicat à la carte non Commune siège Bernaville Arrondissement Amiens Département Somme Interdépartemental non Date de création Date de création 01/01/2015 Date d'effet 01/01/2015 Organe délibérant Mode de répartition des sièges Nombre de sièges dépend de la population Nom du président M. Daniel POTRIQUIER Coordonnées du siège Complément d'adresse du siège 23 rue du Général Jean Crépin Numéro et libellé dans la voie Distribution spéciale Code postal - Ville 80370 BERNAVILLE Téléphone Fax Courriel [email protected] Site internet Profil financier Mode de financement Contributions budgétaires des membres Bonification de la DGF non Dotation de solidarité communautaire (DSC) non Taxe d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (TEOM) non Autre taxe non Redevance d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (REOM) non Autre redevance non 1/3 Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 Population Population totale regroupée 4 573 Densité moyenne 35,28 Périmètres Nombre total de membres : 19 - Dont 19 communes membres : Dept Commune (N° SIREN) Population 80 Autheux (218000404) 123 80 Beaumetz (218000669) 225 80 Bernaville (218000826) 1 079 80 Berneuil (218000859) 266 80 Boisbergues (218001030) 76 80 Bonneville (218001071) 340 80 Domesmont (218002350) 42 80 Épécamps (218002590) 5 80 Fieffes-Montrelet (218005528) 342 80 Fienvillers (218002962) 698 80 Fransu (218003341) 182 -

Département De La Somme Enquête Publique Unique Présentée Par La

p. 1 Département de la Somme Enquête publique unique présentée par La Communauté de Communes du Territoire Nord Picardie (CCTNP) portant sur • L’élaboration du Plan Local d’Urbanisme intercommunal (PLUi) du Bernavillois, valant programme local de l’habitat • Le Règlement Local de Publicité Intercommunal (RLPi) Période d’enquête du 19 juin au 20 juillet 2017 sur une période de 32 jours Prescrite par arrêté De Monsieur le Président de la CCTPN en date du 10 mai 2017 Rapport d’enquête présenté par le commissaire-enquêteur désigné par Ordonnance n° E1700006080 du 04/04/2017, modifié le 18/05/2017, de Monsieur le Président du Tribunal administratif d’Amiens M. Bernard GUILBERT Commissaire-enquêteur. Elaboration du Plan local d’urbanisme intercommunal (PLUi) du Bernavillois Enquête publique n° E17000060/80 p. 2 Table des matières I. GENERALITES CONCERNANT LE PROJET SOUMIS A ENQUETE PUBLIQUE ............................................ 5 A. Objet de l’enquête publique ............................................................................................................................. 5 B. Cadre réglementaire......................................................................................................................................... 5 C. Composition du dossier .................................................................................................................................... 6 D. Nature et caractéristiques du projet de PLUi du Bernavillois .......................................................................... -

Commune De DOULLENS

Commune de DOULLENS Archives communales déposées (archives antérieures à 1790) R épertoire numérique établi par Sophie SEDILLOT, Docteur en droit, vacataire aux Archives Départementales de la Somme. Sous la direction de Frédérique HAMM, Conservateur du Patrimoine, Directrice des Archives Départementales de la Somme. Roland SEENE, Attaché de Conservation du Patrimoine, responsable du service d’aide aux communes. Identification du fonds Références : FR AD 80/26 E-DEP (fonds déposé) Intitulé : Commune de Doullens, Archives communales anciennes déposées aux Archives Départementales de la Somme. Le niveau de description choisi est le fonds. Date de la création des documents : Les documents présents dans le fond de Doullens ont été créés entre 1202 et 1791. Importance matérielle : 269 articles, 11,00 mètres linéaires. Producteur : Mairie de Doullens N° Insee : 253 Adresse de la Mairie : 2 avenue Foch N° Téléphone : 03 22 77 00 07. Répertoire des archives communales de Doullens (fonds ancien), déposées aux Archives départementales de la Somme 2/31 Contexte de production Ce fonds appartient aux Archives communales de Doullens, commune de 7 196 habitants1 dans le département de la Somme. Les archives présentes dans ce fonds ne sont pas uniquement produites par la commune de Doullens. La commune, en effet, a reçu dans l’exercice de son activité des documents produits par d’autres administrations d’Ancien Régime (Intendance, Conseil du roi, Parlement, Contrôle général des Finances….), elle a également recueilli des documents venant de fonds privés composés pour certains de documents n’émanant pas de la commune. Historique de la conservation et des modalités d’entrée du fonds Le conseil municipal de Doullens, dans un souci de respect et de sauvegarde du patrimoine écrit de sa commune, a accepté la proposition de dépôt de ses archives jusqu’en 1939 inclus, aux Archives départementales de la Somme, par un contrat de dépôt du 15 juin 1999. -

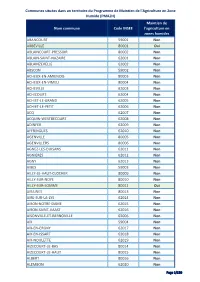

(PMAZH) Nom Commune Code INSEE

Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ABANCOURT 59001 Non ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Non ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Non ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Non ACHICOURT 62004 Non ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Non ADINFER 62009 Non AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Non AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Non AIBES 59003 Non AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Non AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Non AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Non AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Non AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Non AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Non Page 1/130 Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Non ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Non ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Non ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Non AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Non AMY -

PROCES-VERBAL Conseil Communautaire Du Jeudi 04 Juillet

PROCES-VERBAL Conseil communautaire du jeudi 04 juillet 2019 18 heures – Espace culturel de Doullens Page 1 sur 73 COMPOSITION Le Président Monsieur Laurent SOMON Bernaville 1er Vice-président Monsieur Claude DEFLESSELLE Coisy En charge de l’économie et des finances 2e Vice-président Monsieur Christian VLAEMINCK Doullens En charge des bâtiments 3e Vice-président Monsieur Jean-Michel MAGNIER Beaumetz En charge du scolaire 4e Vice-président Monsieur Jean-Michel BOUCHY Naours En charge du tourisme 5e Vice-président Monsieur Francis PETIT Grouches-Luchuel En charge de la GEMAPI 6e Vice-président Monsieur Daniel POTRIQUIER Bonneville En charge de l’eau et l’assainissement 7e Vice-président Monsieur Laurent CRAMPON Montonvillers En charge de l’enfance et la jeunesse 8e Vice-président Monsieur François DURIEUX Beauquesne En charge de l’urbanisme et de la planification 9e Vice-président Monsieur Patrick BLOCKLET Talmas En charge de la voirie 10e Vice-présidente Madame Christelle HIVER Doullens En charge du personnel 11e Vice-président Monsieur Dominique HERSIN Candas En charge du social 12e Vice-présidente Madame Anne-Sophie DOMONT Villers-Bocage En charge de la culture 13e Vice-présidente Madame Catherine PENET-CARON Humbercourt En charge de l’insertion Membres du Bureau communautaire : 1. Monsieur Frédéric AVISSE Molliens-au-Bois 2. Monsieur Jean Pierre DOMONT Villers-Bocage 3. Madame Annie MARCHAND Beaucourt-sur-l’Hallue 4. Monsieur Philippe PLAISANT Béhencourt 5. Monsieur Jean-Marie ROUSSEAUX Rubempré 6. Monsieur Bernard THUILLIER Beauval 7. Monsieur François CREPIN Longuevillette 8. Monsieur Alain CHEVALIER Gézaincourt 9. Monsieur Pascal PIOT Doullens 10. Monsieur William NGASSAM Doullens 11. Monsieur Dany CHOQUET Heuzecourt 12. -

Vallée De L'authie

Réunions d’information Pour répondre à toutes vos interrogations, la Chambre d’agriculture et les partenaires de l’éle- vage organisent deux après-midi en exploitation. Info RAPIDE é Le 13 mai chez Stéphane Montaigne à Maison Ponthieu Vallée de l’Authie é Le 22 mai au GAEC Mercier à Candas Avril 2014 Rendez-vous à 14 h 00 (parcours fléché dans le village). e 28 décembre 2012, le préfet de bassin a pris un arrêté classant les communes de la Vallée de l’Authie en zone vulnérable et ceci malgré les avis contraires d’un certain Lnombre d’institutions et l’argumentaire de la profession. La Fdsea a déposé un re- Au programme : cours au tribunal administratif qui à ce jour n’a donné aucune réponse. L’Agence de l’Eau Artois-Picardie a voté une enveloppe de subvention pour accompagner les éleveurs dans - Rappel de la réglementation et des nouvelles dispositions propres à la vallée de l’Authie la réalisation de capacités de stockage afin de répondre aux nouvelles règles imposées par ce classement. Compte-tenu de l’enjeu que représente l’élevage sur cette zone, nous - Cas pratiques à partir des exploitations visitées, capacités de stockage et contraintes environ- ne pouvons que répondre favorablement à ce dispositif d’aides, sans pour autant faire nementales abstraction du recours intenté par la profession agricole. Je vous engage à participer aux - Présentations des solutions techniques pour le stockage des effluents Daniel ROGUET Président de la différentes journées d’information afin de mieux appréhender les nouvelles règles et les - Présentation du programme d’aide spécifique de l’Agence de l’Eau Artois-Picardie et des autres Chambre d'agriculture réponses techniques et financières qui peuvent être apportées. -

[email protected] 133

132 344o INFANTERIE-DIVISION - UNIT HISTORY DATE LOCATION ACTIVITY CHAIN OF COMMAND 1942/09/24 Stuttgart, Wehrkreis V Activation of the 344.ID (bodenst.) Subordinate to: Wehrbezirkskommando II Stuttgart, (IS.Welle) 1942/09/24-1942/09/27 1942/09/26 Bordeaux, Dax, France Formation C.O*: Gen.Lto Felix Schwalbe, 1942/09/27-1944/10/16 Subordinate to: AOK 1 Bordeaux, 1942/09/28-1942/10/31 1942/10/16 Truppenuebungsplatz Champ de Souge Training AK 80 Poitiers, 1942/11/01-1942/11/30 1942/11/23 Kuestenverteidigungsabschnitt Coastal defense, AK 86 Dax, 1942/12/01-1942/12/31 Arcachon, Andernos-les-Bains, occupation duty Le Verdon-sur-Mer, Mimizan Records of the 344.ID (bodenst.) are reproduced on roll 2141 of NARS Microfilm Publication T315 and are described following the unit history. Although only a few record items of this division were available in the National Archives, situation maps of Lage West and Ost, the general officer personnel files, and manuscripts in the Foreign Military Studies series, show: 1943/01/01 Kuestenverteidigungsabschnitt Coastal defense, Arcachon occupation duty 1944/01/01 Somme sector (Abschnitt Berck) Transfer, coastal defense, construction of strong points, launching of V-l 1944/08/04 Barentin, Relief by the 490 and 348.ID, StoPierre-de-Varengeville movement, defensive operations 1944/08/09 Bernay, Laigle, Verneuil, Movement, defensive operations, Breteuil, Conches, Le Neubourg transfer of combat troops to the 3310ID 1944/08/25 Barentin Assembly of division remnants 1944/08/27 Serqueux, Amiens, Autheux, Fruges, Withdrawal, Beaumetz, Aire, Hazebrouck, defensive operations France; Dixmuiden, Bruges, Lembeke, Overpelt, Belgium www.maparchive.ru [email protected] 133 DATE LOCATION ACTIVITY CHAIN OF COMMAND 1944/09/06 Ijzendijke, Breskens, Ferrying AOK 15 across river, Meuse and Scheldt Rivers, defensive operations, Venlo, Netherlands 1944/09/23 Dordrecht, Gorinchem Withdrawal, position defense 1944/10/01 Lintfort, Germany Withdrawal, defensive operations, C000: Obst. -

Sectorisation Par Commune

Conseil départemental de la Somme / Direction des Collèges Périmètre de recrutement des collèges par commune octobre 2019 Code communes du secteur Libellé du secteur collège commune 80001 Abbeville voir sectorisation spécifique 80002 Ablaincourt-Pressoir CHAULNES 80003 Acheux-en-Amiénois ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80004 Acheux-en-Vimeu FEUQUIERES EN VIMEU 80005 Agenville BERNAVILLE 80006 Agenvillers NOUVION AGNIERES (ratt. à HESCAMPS) POIX 80008 Aigneville FEUQUIERES EN VIMEU 80009 Ailly-le-Haut-Clocher AILLY LE HAUT CLOCHER 80010 Ailly-sur-Noye AILLY SUR NOYE 80011 Ailly-sur-Somme AILLY SUR SOMME 80013 Airaines AIRAINES 80014 Aizecourt-le-Bas ROISEL 80015 Aizecourt-le-Haut PERONNE 80016 Albert voir sectorisation spécifique 80017 Allaines PERONNE 80018 Allenay FRIVILLE ESCARBOTIN 80019 Allery AIRAINES 80020 Allonville RIVERY 80021 Amiens voir sectorisation spécifique 80022 Andainville OISEMONT 80023 Andechy ROYE ANSENNES ( ratt. à BOUTTENCOURT) BLANGY SUR BRESLE (76) 80024 Argoeuves AMIENS Edouard Lucas 80025 Argoules CRECY EN PONTHIEU 80026 Arguel BEAUCAMPS LE VIEUX 80027 Armancourt ROYE 80028 Arquèves ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80029 Arrest ST VALERY SUR SOMME 80030 Arry RUE 80031 Arvillers MOREUIL 80032 Assainvillers MONTDIDIER 80033 Assevillers CHAULNES 80034 Athies HAM 80035 Aubercourt MOREUIL 80036 Aubigny CORBIE 80037 Aubvillers AILLY SUR NOYE 80038 Auchonvillers ALBERT PM Curie 80039 Ault MERS LES BAINS 80040 Aumâtre OISEMONT 80041 Aumont AIRAINES 80042 Autheux BERNAVILLE 80043 Authie ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80044 Authieule DOULLENS 80045 Authuille