Zambia June 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Iccf Group Brochure Ed

THE ICCF GROUP BROCHURE ED. 2021-2022 INTERNATIONALCONSERVATION.ORG TABLE OF CONTENTS WHO WE ARE AND WHAT WE DO ................................................................ 4 WORKING WITH LEGISLATURES ..................................................................... 8 • Caucuses We Support ................................. 10 • ICCF in the United States ................................ 12 • The ICCF Group in the United Kingdom ......................................................................................................... 31 • The ICCF Group in Latin America & the Caribbean ...................................................................................... 39 • The ICCF Group in Africa ............................ 63 • The ICCF Group in Southeast Asia ................ 93 WORKING WITH MINISTRIES ....................................................................... 103 MISSION THE MOST ADVANCED WE WORK HOW TO ADVANCE SOLUTION IN CONSERVATION CONSERVATION GOVERNANCE GOVERNANCE BY BUILDING 1. WE BUILD POLITICAL WILL POLITICAL WILL, The ICCF Group advances leadership in conservation by building political will among parliamentary PROVIDING and congressional leaders, and by supporting ministries in the management of protected areas. ON-THE-GROUND SOLUTIONS 2. CATALYZING CHANGE WITH KNOWLEDGE & EXPERTISE We support political will to conserve natural resources by catalyzing strategic partnerships and knowledge sharing between policymakers and our extensive network. VISION 3. TO PRESERVE THE WORLD'S MOST CRITICAL LANDSCAPES -

Zambia National Programme Policy Brief

UN-REDD ZAMBIA NATIONAL PROGRAMME POLICY BRIEF DRIVERS OF DEFORESTATION AND POTENTIAL FOR REDD+ INTERVENTIONS IN ZAMBIA Jacob Mwitwa, Royd Vinya, Exhildah Kasumu, Stephen Syampungani, Concilia Monde, and Robby Kasubika Background Deforestation and poor forest stewardship reduce carbon stocks and the capacity for carbon storage in Zambian forests. Forest loss is caused by a mix of factors that are not well understood, and their combined effects act to either directly drive forest cover loss or interact with other or influences. In order to understand the drivers and their interactions a study was commissioned to provide a preliminary understanding of drivers of deforestation and the potential for forest types (Fanshawe 1971; White 1983); to differ REDD+ in Zambia; to assess the extent of current substantially in the key drivers of deforestation consumption of forest products, forest production (ZFAP 1998); and have diverse cultural and socio- and development trends as well as potential future economic settings. Sample selection of districts shifts in these patterns that may affect deforestation was based on review of statistics from isolated case levels; to draw conclusions on which actions/trends studies and on analysis of land cover maps and would likely have the worst consequences in terms satellite images. of causing additional deforestation and how these could be reduced in future; and finally to outline the potential for REDD+ in these circumstances. Vegetation Types Of Zambia An interdisciplinary data gathering approach was Zambia has three major vegetation formations. The adopted which integrated literature search, policy closed forests are limited in extent, covering only level consultancy, community level consultations, about 6% of the Country. -

Report20 Uniting to End Malaria 501(C)3

PHOTO BY PAUL ISHII ANNUAL REPORT20 Uniting to End Malaria 501(c)3. EIN: 46-1380419 No one can foresee the duration or severity of COVID’s human and economic toll. But the malaria global health community agrees it will be disastrous to neglect or underinvest in malaria during this period, and thereby squander a decade of hard won progress. By some estimates, halting malaria intervention efforts could trigger a return to one million malaria deaths per year, a devastating mortality rate unseen since 2004. To that end many of our efforts last year were to strategically advocate for continued global malaria funding, as well as supporting COVID adjustments to ensure malaria projects were not delayed. Last year we supplied Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) to over 700 Rotary-funded community health workers (CHWs) in Uganda and Zambia; altered CHW The training to incorporate appropriate social distancing; conducted several webinars specifically focused on maintaining malaria financial support despite COVID; and we provided $50,000 to the Alliance for Malaria Prevention used for COVID/malaria public education in Africa. Jeff Pritchard Board Chair While our near-term work must accommodate pandemic restrictions, we are still firmly committed to our mission, “to generate a broad international Rotary campaign for the global elimination of malaria.” During the coming twelve months we intend to: • Implement a blueprint developed in 2020 for a large long-term Road malaria program with Rotary, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and World Vision, in the most underserved regions of Zambia’s Central and Muchinga Provinces, positively impacting nearly 1.4 million residents. -

Agrarian Changes in the Nyimba District of Zambia

7 Agrarian changes in the Nyimba District of Zambia Davison J Gumbo, Kondwani Y Mumba, Moka M Kaliwile, Kaala B Moombe and Tiza I Mfuni Summary Over the past decade issues pertaining to land sharing/land sparing have gained some space in the debate on the study of land-use strategies and their associated impacts at landscape level. State and non-state actors have, through their interests and actions, triggered changes at the landscape level and this report is a synthesis of some of the main findings and contributions of a scoping study carried out in Zambia as part of CIFOR’s Agrarian Change Project. It focuses on findings in three villages located in the Nyimba District. The villages are located on a high (Chipembe) to low (Muzenje) agricultural land-use gradient. Nyimba District, which is located in the country’s agriculturally productive Eastern Province, was selected through a two-stage process, which also considered another district, Mpika, located in Zambia’s Muchinga Province. The aim was to find a landscape in Zambia that would provide much needed insights into how globally conceived land-use strategies (e.g. land-sharing/land-sparing trajectories) manifest locally, and how they interact with other change processes once they are embedded in local histories, culture, and political and market dynamics. Nyimba District, with its history of concentrated and rigorous policy support in terms of agricultural intensification over different epochs, presents Zambian smallholder farmers as victims and benefactors of policy pronouncements. This chapter shows Agrarian changes in the Nyimba District of Zambia • 235 the impact of such policies on the use of forests and other lands, with agriculture at the epicenter. -

Provincial Health Literacy Training Report Northern and Muchinga Provinces

Provincial Health Literacy Training Report Northern and Muchinga Provinces AT MANGO GROVE LODGE, MPIKA, ZAMBIA 23-26TH APRIL 2013 Ministry of Health and Lusaka District Health Team, Zambia in association with Training and Research Support Centre (TARSC) Zimbabwe In the Regional Network for Equity in Health in east and southern Africa (EQUINET) With support from CORDAID 1 Table of Contents 1. Background ......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Opening .............................................................................................................................. 4 3. Ministry of Health and LDHMT ............................................................................................ 5 3.1 Background information on MOH ................................................................................. 5 3.2 Background on LDHMT ............................................................................................... 6 4. Using participatory approaches in health ............................................................................ 7 5. The health literacy programme ............................................................................................ 9 5.1 Overview of the Health literacy program ...................................................................... 9 5.2 Using the Zambia HL Manual ......................................................................................10 5.3 Social mapping ...........................................................................................................10 -

Socio-Economic Impact of Small Scale Emerald Mining on Local Community Livelihoods: the Case of Lufwanyama District

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 3 No. 6 June 2015 SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT OF SMALL SCALE EMERALD MINING ON LOCAL COMMUNITY LIVELIHOODS: THE CASE OF LUFWANYAMA DISTRICT Precious Moyo Shoko Precious Moyo Shoko has been graduate student studying for her MA in peace and conflict studies in the Dag Hammarskjöld Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies of the Copperbelt University. She specialised in environment and sustainable development for which this article is a part of her research output. She is the corresponding author. Her address is The Copperbelt University, DHIPS, P.O. Box 21692, Kitwe, Zambia, Mobile No: +260 977 674 743, Email: [email protected] Jacob Mwitwa Jacob Mwitwa is a Professor of natural resources management in the Copperbelt University in Zambia. He currently is in charge of Research and Innovation for the Copperbelt University. He has over 20 years of experience in natural resources management, environmental resources policy, rural livelihoods and conservation, and project management. He holds a PhD from the University of Stellenbosch and has published two books, and articles in peer-reviewed journals. His major research interest lie in resource rights and governance of environmental resources in the context of mining, climate change and protected area management. Professor Jacob Mwitwa contacts are School of Natural Resources, The Copperbelt University, P.O. Box 21692, Kitwe, Zambia, Mobile No: +260 977 848 462/966 848 462, Email: [email protected] Abstract Lufwanyama district has some of the world’s best emeralds and mining, is not contributing to the local economic development. Mining has failed to stimulate local enterprises, traditional industries and access to environmental resources. -

Can Design Thinking Be Used to Improve Healthcare in Lusaka Province, Zambia?

INTERNATIONAL DESIGN CONFERENCE - DESIGN 2014 Dubrovnik - Croatia, May 19 - 22, 2014. CAN DESIGN THINKING BE USED TO IMPROVE HEALTHCARE IN LUSAKA PROVINCE, ZAMBIA? C. A. Watkins, G. H. Loudon, S. Gill and J. E. Hall Keywords: ethnography, design thinking, Zambia, healthcare 1. Background ‘Africa experiences 24% of the global burden of disease, while having only 2% of the global physician supply and spending that is less than 1% of global expenditures.’ [Scheffler et al. 2008]. Every day the equivalent of two jumbo jets full of women die in Childbirth; 99% of these deaths occur in the developing world [WHO 2012]. For every death, 20 more women are left with debilitating conditions, such as obstetric fistula or other injuries to the vaginal tract [Jensen et al. 2008]. In the last 50 years, US$2.3 trillion has been spent on foreign aid [Easterly 2006]; US$1 trillion in Africa [Moyo 2009]. Despite this input, both Easterly and Moyo argue there has been little benefit. Easterly highlights that this enormous donation has not reduced childhood deaths from malaria by half, nor enabled poor families access to malaria nets at $4 each. Hodges [2007] reported that although equipment capable of saving lives is available in developing countries, more than 50% is not in service. Studies have asked why this should be so high [Gratrad et al. 2007], [Dyer et al. 2009], [Malkin et al. 2011] the majority focussing on medical equipment donation. They suggest that it is not feasible to directly donate equipment from high to low-income settings without understanding how the receiving environment differs from that which it is designed for. -

Rice Production Diagnostic for Chinsali and Mfuwe, Zambia

Rice production diagnostic for Chinsali (Chinsali District, Northern Province) and Mfuwe (Mwambe District, Eastern Province), Zambia By Erika Styger July 2014 For COMACO and David R. Atkinson Center for Sustainable Development Rice production diagnostic for Chinsali (Chinsali District, Northern Province) and Mfuwe (Mwambe District, Eastern Province), Zambia Written by Erika Styger, SRI International Network and Resources Center (SRI-Rice), International Programs, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA All photos by Erika Styger For COMACO, Lusaka, Zambia and David R. Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA © 2014 SRI International Network and Resources Center (SRI-Rice), Ithaca, NY For more information visit http://sri.cals.cornell.edu/, or contact Erika Styger ([email protected]) Rice diagnostic for Chinsali and Mfuwe, Zambia; by Erika Styger, Cornell University, July 2014 ([email protected]) 2 Table of Content Table of Content 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Rice systems in Zambia and COMACO rice production zones 7 3. Northern Floodplain Rice Production zone, Chinsali District, Northern Province 9 3.1. Agricultural system overview 9 3.2. Rice production practices 10 3.3. The application and performance of the System of Rice Intensification 11 3.4. Challenges and constraints to rice intensification 13 3.5. Description of three lowland rice production zones in Chinsali 15 3.6. Adaptation to climate variability – opportunities for intensification 16 3.7. Chama rice quality loss 18 3.8. Implementation strategies for rice intensification for the 2014/2015 cropping 20 season 4. Dambo Rice Production Zone, Mfuwe, Mwambwe District, Eastern Province 23 4.1. -

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly Progress Report Grantee Name: Maternal and Child Survival Program Grant Number: # AID-OAA-A-14-00028 Primary contact person regarding this report: Mira Thompson ([email protected]) Reporting for the quarter Period: Year 3, Quarter 1 (October –December 2018) 1. Briefly describe any significant highlights/accomplishments that took place during this reporting period. Please limit your comments to a maximum of 4 to 6 sentences. During this reporting period, MCSP Zambia: Supported MOH to conduct a data quality assessment to identify and address data quality gaps that some districts have been recording due to inability to correctly interpret data elements in HMIS tools. Some districts lacked the revised registers as well. Collected data on Phase 2 of the TA study looking at the acceptability, level of influence, and results of MCSP’s TA model that supports the G2G granting mechanism. Data collection included interviews with 53 MOH staff from 4 provinces, 20 districts and 20 health facilities. Supported 16 districts in mentorship and service quality assessment (SQA) to support planning and decision-making. In the period under review, MCSP established that multidisciplinary mentorship teams in 10 districts in Luapula Province were functional. Continued with the eIMCI/EPI course orientation in all Provinces. By the end of the quarter under review, in Muchinga 26 HCWs had completed the course, increasing the number of HCWs who improved EPI knowledge and can manage children using IMNCI Guidelines. In Southern Province, 19 mentors from 4 districts were oriented through the electronic EPI/IMNCI interactive learning and had the software installed on their computers. -

Occurrence of Cholera in Lukanga Fishing Camp, Kapiri-Mposhi District, Zambia

OUTBREAK REPORT Occurrence of cholera in Lukanga fishing camp, Kapiri-mposhi district, Zambia R Murebwa-Chirambo1, R Mwanza2, C Mwinuna3, ML Mazaba1, I Mweene-Ndumba1, J Mufunda1 1. World Health Organization, Country office, Lusaka, Zambia 2. Ministry of Health, Provincial Health Office, Kabwe, Zambia 3. Ministry of Health, District Health Office, Kapiri Mposhi, Zambia Correspondence: Rufaro Murembwa-Chirambo ([email protected]) Citation style for this article: Murebwa-Chirambo R, Mwanza R, Mwinuna C, Mazaba ML, Mweene-Ndumba I, Mufunda J. Occurrence of cholera in Lukanga fishing camp, Kapiri-mposhi district, Zambia. Health Press Zambia Bull. 2017;1(1) [Inclusive page numbers] Most of the cholera outbreaks in Zambia have been There is need to employ interventions in the area of recorded from fishing camps and peri-urban areas of water and sanitation on the Lukanga swamps in order the Copperbelt, Luapula and Lusaka provinces. to address the annual cholera outbreaks. Cholera cases have been recorded every year in the Lukanga fishing camps in the last five years. This article Introduction documents a cholera outbreak reported at the Lukanga The first outbreak of cholera in Zambia was fishing camp in Kapiri Mposhi district in September, 2016. All cases that met the cholera case definition as reported in 1977/1978, then cases appeared prescribed in the Integrated Diseases Surveillance and again in 1982/1983. The first major outbreak Response guidelines were admitted and treated using occurred in 1990 and lasted until 1993. Since WHO standard protocols. A total of 27 patients all adult except 1, 26 of whom were male were seen at the cholera then, cholera cases were registered every treatment center. -

Zambia Health Sector Public Expenditure Tracking and Quantitative Service Delivery Survey

Public Disclosure Authorized Zambia Health Sector Public Expenditure Tracking and Quantitative Service Delivery Survey Public Disclosure Authorized Collins Chansa Thulani Matsebula Moritz Piatti Dale Mudenda Chitalu Miriam Chama-Chiliba Bona Chitah Oliver Kaonga Chris Mphuka Public Disclosure Authorized April 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. -

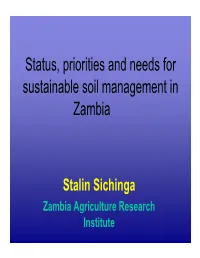

Status, Priorities and Needs for T I Bl Il T I Sustainable Soil Management In

Status, priorities and needs for sustitaina ble so il managemen tit in Zambia SSStalin Sichinga Zamb ia Ag ricu ltu re Resea r ch Institute Introduction Zambia has an area of 750,000 km2 with about 13.9 million people and ample land resources 0ut of 9 million ha cultivable land, only 14% is cropped in any year About 55 - 60% of the land area is covered by natural forest and 6% of Zambia‘s land surface is covered by water. Agro-ecological regions and soil distribution The country is classified into three agro-ecological regions based on soil types, rainfall, and other climatic conditions Agro-Ecological Regions N Chiengi Kaputa Mpulungu W E Nchelenge Mbala Nakonde Mporokoso S Kawambwa Mungwi Isoka Scale 1: 2,500,000 Mwense Luwingu Kasama Chinsali Chilubi Mansa Chama LEGEND Samfya Milenge Mpika Regions Mwinilunga Chililabombwe Solwezi Agro-ecological Region I Chingola Mufulira Lundazi I Ka lul u shi Kitwe Ndola IIa Lufwanyama Luans hya Chavuma Serenje Mambwe Kabompo Masaiti IIb Mpongwe Zambezi Mufumbwe Chipata Kasempa Petauke Katete Chadiza III Annual rainfall is <750mm Kapiri Mposhi Mkushi Nyimba Kabwe Lukulu Kaoma Mumbwa Chibombo Kalabo Mongu Chongwe Lusaka Urban Luangwa Itezhi-Tezhi Kafue Namwala Mazabuka Senanga Monze KEY Siavonga Sesheke Gwembe Shangombo Choma District boundary e Kazungula Kalomo w g n o z a in Livingstone S 200 0 200 400 Kilometers December 2002 The region contains a diversity of soil types ranging from slightly acidic Nitosols to alkaline Luvisols with pockets of Vertisols, Arenosols, Leptosols and, Solonetz. The physical limitations of region I soils Hazards to erosion, lim ite d so il dept h in t he hills an d escarpment zones, presence of hardpans in the pan dambo areas, ppyoor workability in the cracking gy, clay soils, problems of crusting in most parts of the Southern province, low water-holding capacities and the problem of wetness in the valley dambos, plains and swamps.