The Kirktown of Rothiemay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydrology Hydrogeology and Geology.Pdf

HYDROLOGY, HYDROGEOLOGY AND GEOLOGY 11 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 1 LEGISLATION, PLANNING POLICY AND GUIDANCE ............................................................................. 1 Legislation ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 Planning Policy ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Guidance ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 SCOPE AND CONSULTATION .............................................................................................................. 4 Consultation .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Effects Assessed in Full .................................................................................................................................. 5 Effects Scoped Out ........................................................................................................................................ 6 APPROACH AND METHODS ............................................................................................................... 6 Assessment -

Minutes – AGM 15Th Sep 2016

MINUTES of THE COMBINED ANNUAL MEETING of QUALIFIED PROPRIETORS of THE RIVER DEVERON DISTRICT SALMON FISHERY and ANNUAL PUBLIC OPEN MEETING held at CASTLE HOTEL, HUNTLY on Thursday, 15th SEPTEMBER 2016 at 5pm Present: A Allwood (Muiresk), Mrs M Burnett-Stuart (Ardmeallie, Boat of Turtory), R Cooper (Mains of Auchingoul), J Cruickshank (Carnousie, Ardmiddle, Inverkeithny Glebe, Inverkeithny, Upper Netherdale, Lower Netherdale), M Hay (Edinglassie) also as mandatory for J G Brown’s Trust (Coniecleugh), Glennie 2011 Settlement (Tillydown), Ms I Hofmann (Lesmurdie), A G Morison (Mountblairy and Bognie), A Cheyne (Mains of Mayen and Mayen & Garronhaugh), A D Tennant (Forglen), Mrs D A Stancioff (Dunlugas), J Ingleby (Cairnborrow & Blairmore), Mrs P Ingleby (Mains of Aswanley), W Booth (Duff House), D Borthwick (co-optee represents salmon anglers) as mandatory for Huntly Fishings, F Henderson (co-optee represents salmon anglers), R Breakell (co-optee represents salmon anglers), D Galloway as mandatory for Banff & Macduff Angling Association (River Deveron), Mrs J Player as mandatory for J player (Upper Inverichnie), J Begg as mandatory for Mr & Mrs D A Sharp (Corniehaugh), M Crossley as mandatory for Turriff Angling Association. Also in attendance: Mrs S Paxton (Clerk to the Board); J Minty (River Bailiff); R Miller (River Director); six members of the public including members of the Deveron, Bogie and Isla Rivers Charitable Trust, Ghillies, Estate Managers and Anglers. Apologies for Absence: CR Marsden and MCR Marsden (Duff House); J G Brown’s Trust (Coniecleuch); Glennie 2011 Settlement (Tillydown) (per R Foster); I Hofmann (Lesmurdie); Mr & Mrs D A Sharp (Corniehaugh); A Higgins (Castle Fishings); J D Player (Lower Inverichnie); Messers F M Stewart & Sons (Gibston); R Shields (Avochie); Mrs D Goucher (Eden South, Lower Inverichnie); Belcherrie Farms Partnership (Lynebain); C Innes (Euchrie & Kinnairdy). -

Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19

The River Deveron District www.deveron.org Salmon Fishery Board The Deveron, Bogie and Isla Rivers Charitable Trust Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19 The Offices, Avochie Stables, Avochie, Huntly, Aberdeenshire AB54 7YY Tel: 01466 711 388 email: [email protected] www.deveron.org Report by RC Miller, MC Hay, M Walters and S Roebuck The Offices, Avochie Stables, Avochie, Huntly, Aberdeenshire AB54 7YY Tel: 01466 711 388 email: [email protected] www.deveron.org 3 Contents DeveronBogieIsla @DBIRCT FRONT COVER: The Deveron at Rothiemay river_deveron 05 Supporters and Funding Officials and Staff 06 Chairman’s Report View it at Henderson’s Country Sports 08 Deveron Salmon 26 Education and Community Outreach 09 Deveron Sea Trout Deveron Opening Ceremony and Morison Trophy Conservation Code and Statutory Regulations 28 Good Governance 10 2018 Catches 30 The Deveron, Bogie and Isla Rivers Charitable Trust accounts 11 Management Report 34 The River Deveron District 14 Angler’s Map of the River Deveron Salmon Fishery Board accounts 2019/20 Priorities 36 Deveron Angling Code for 16 Research and Monitoring Salmon and Trout 2019 Deveron Annual Report 2018/19 5 Supporters and Funding Officials and Staff The River Deveron District Salmon Fishery Board (RDevDSFB) The River Deveron District Salmon Fishery Board Members and The Deveron, Bogie and Isla Rivers Charitable Trust (DBIT) Representatives of upper proprietors would like to take this opportunity to thank all its supporters and M.C. Hay (Chairman), R.J.G. Shields, A.G. Morison, Mrs J.A. Player, funding partners who have helped implement our district fisheries R. Cooper, J.S. -

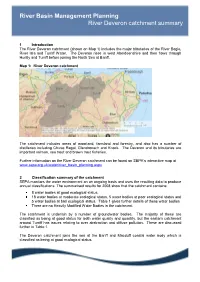

River Basin Management Planning River Deveron Catchment Summary

River Basin Management Planning River Deveron catchment summary 1 Introduction The River Deveron catchment (shown on Map 1) includes the major tributaries of the River Bogie, River Isla and Turriff Water. The Deveron rises in west Aberdeenshire and then flows through Huntly and Turriff before joining the North Sea at Banff. Map 1: River Deveron catchment The catchment includes areas of moorland, farmland and forestry, and also has a number of distilleries including Chivas Regal, Glendronach and Knock. The Deveron and its tributaries are important salmon, sea trout and brown trout fisheries. Further information on the River Deveron catchment can be found on SEPA’s interactive map at www.sepa.org.uk/water/river_basin_planning.aspx 2 Classification summary of the catchment SEPA monitors the water environment on an ongoing basis and uses the resulting data to produce annual classifications. The summarised results for 2008 show that the catchment contains: 8 water bodies at good ecological status. 18 water bodies at moderate ecological status, 5 water bodies at poor ecological status and 5 water bodies at bad ecological status. Table 1 gives further details of these water bodies. There are no Heavily Modified Water Bodies in the catchment. The catchment is underlain by a number of groundwater bodies. The majority of these are classified as being at good status for both water quality and quantity, but the eastern catchment around Turriff has issues relating to over abstraction and diffuse pollution. These are discussed further in Table 1. The Deveron catchment joins the sea at the Banff and Macduff coastal water body which is classified as being at good ecological status. -

The Integration Of.Pdf

The Archives of Automotive Engineering – Archiwum Motoryzacji Vol. 85, No. 3, 2019 103 THE INTEGRATION OF PASSENGER TRANSPORT AND INTEGRATION BARRIERS OI EWHRUDJAKPOR1, ADELA POLIAKOVÁ2, MILOŠ POLIAK3 Abstract The paper deals with the issue of supporting public passenger transport and it is integration with the aim of ensuring the sustainable mobility of population. The paper points to the importance of public passenger transport and the reasons why the population prefers cars. Based on the analysis, it is arguable that public passenger transport without mutual integration is not capable enough to compete with individual motoring. Contribution proposes the process integration of public passenger transport as a key elements in increasing road safety. Contribution confirms the hypothesis that the integration of public passenger transport and achieving a higher use of public passenger transport of population can contribute to improving of road safety. Keywords: transportation; behavior; safety; process; integration 1. Introduction Transport strategy in European Union supports public transport against individual transport. The reason is using of public transport is possible to fulfil all the goals of the EU strategy in the field of road safety. This is particularly the stabilization of the increase in entitlements of road transport on infrastructure where dissemination is problematic especially inside in the territory of the town. Building of a new of expressway infrastructure for growing trans- port outputs is a long term problem, particularly in the context of an aging EU population. Support of public passenger transport brings lower fuel consumption. It is achieved by an- other strategic objective of EU transport and reducing dependence on oil as feedstock that is imported into the EU. -

Huntly Lodge Can Be Seen Seen Be Can Lodge Huntly Distance O

Huntly Lodge Huntly Farm Did you know... 1 The bridge is thought to have been constructed sometime between the Marquis Hotel House late 1400s and early 1600s. In the Did you know... distance Huntly Lodge can be seen Did you know... Castle Nordic Ski Centre – The Huntly Gardens which is now the Castle Hotel. Linen Thistle (Duke Street) – Meeting Nordic and Outdoor Centre is the In 1756, the DuchessPo tKatherine 22 Walking down Duke Street from 90 B only purpose-built all-weather constructed the Lodge using the Square an archway can be materials from the Castle. seen on the right, above which a facility for cross-country skiing in Britain. Many national thistle can A96be seen. This was a 1 symbol used in the linen industry athletes from the local cross- which Huntly was famous for, country skiing club can be seen especially in the 18th century. swooshing past during a training Kinnoir session! Wood Devil’s Castle Horse Chair Bridge B9022 Pot The Mermaid Bridge of Gibston Nordic Ski Boat Centre & Huntly Hole A Castle 9 River Deveron Cycle Hire Did you know... 6 Hill of Haugh 1 2 Golf Course Duke’s Statue – The statue was erected in 1863 to the 5th Duke of e Recreation Richmond after the death of the last NUE VE Ground A A92 N River Bogi Duke of Gordon. The Stannin Steens 0 A Caravan W M O Park 2 R I o’ Strathbogie can be found at the L Cooper T Ittinstone O N Park Pool W 1 base of Duke’s Statue. -

Strathbogie, Buchan & Northern Aberdeenshire: Huntly

8 Strathbogie, Buchan & Northern Aberdeenshire: Huntly, Auchenhamperis, Turriff, Mintlaw, Peterhead We have grouped the northern outreaches of Aberdeenshire together for the purposes of this project. The areas are quite distinct from each other © Clan Davidson Association 2008 Strathbogie is the old name for Huntly and the surrounding area. This area is quite different from the high plateau farmlands between Turriff and the north coast, and different again from the flat lowland coastal plain of Buchan between Mintlaw and Peterhead. West of Huntly, the landscape quickly changes into a moorland and highland environment. The whole area is sparsely populated. The Davidson history of this area is considerable but not yet well documented by the Clan Davidson, and we hope to complete far more research over the coming years. The Davidsons of Auchenhamperis appear in the early historical references for the North East of Scotland. Our Clan Davidson genealogical records have several references linking Davidsons to this part of Aberdeenshire. Auchenenhamperis is located north east of Huntly and south west of Turriff. Few of the buildings present today appear to have any great ancestry and it is hard to imagine what this area looked like three to four centuries ago. Today, this is open farm country on much improved land, but is sparsely populated. The landscape in earlier times would have been similar, but with far more scrub and unimproved land on the exposed hills, and with more people working the land. Landscape at Auchenhamperis Davidston House is a private house, located just to the south of Keith, which was originally built in 1678 for the Gordon family. -

Notices and Proceedings for Scotland

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER SCOTLAND NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2294 PUBLICATION DATE: 17/08/2020 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 07/09/2020 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Scotland) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 24/08/2020 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. -

21St September, 1994 in a Meeting of the Planning and Development

21st September, 1994 In a Meeting of the Planning and Development Committee of the Moray District Council held at Elgin on the Twenty-first day of September, Nineteen Hundred and Ninety-four. PRESENT Councillors:- I. Lawson (Chairman) J.A. Proctor E. Aldridge Mrs. J.M. Scott A.J. Fleming Mrs. J.M. Shaw T.A. Howe C.R.C. Smith W. Jappy D.M.A. Thompson S.D.I. Longmore J. Wilson IN ATTENDANCE Director of Administration and Law Director of Planning and Development Principal Building Control Officer Chief Assistant, Local Plans & Industry Mr D. Duncan, Senior Assistant, Development Control 1. APOLOGIES Apologies for absence were intimated on behalf of Councillors Mrs. M.E. Anderson, Mrs H.M. Cumiskie, Mrs. M.M. Davidson, L. Mann and W.R. Swanson. 2. ADDITIONAL ITEMS In terms of the relevant Standing Order, the Meeting agreed to accept the following matters as additional items of business to be transacted at the Meeting on the Chairman certifying that, in his opinion, they required to be considered at the Meeting on the grounds of urgency. (i) Proposed Business Shop In order to allow timeous consideration to be given to a report by the Director of Planning and Development advising the Committee of current progress made in regard to the establishment of a proposed business shop within Elgin. (ii) Office and Depot, Mosstodloch Industrial Estate - R & C Murray To allow early consideration to be given to a report by the Estates Surveyor in regard to recent developments regarding the proposed sale of an office and depot at the Mosstodloch Industrial Estate to R & C Murray. -

MORAY LOCAL LANDSCAPE DESIGNATION REVIEW Carol Anderson Landscape Associates – July 2018 DRAFT REPORT CONTENTS

MORAY LOCAL LANDSCAPE DESIGNATION REVIEW Carol Anderson Landscape Associates – July 2018 DRAFT REPORT CONTENTS 1 Background 1 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Approach to the study 2 1.3 Stage One evaluation 2 1.4 Other landscape-based designations in Moray 4 2 Stage One evaluation 15 3 Stage Two candidate Special Landscape Areas 19 Annex A: Stage One evaluation tables 79 Your place, Your plan, Your future Chapter 1 Background Moray Local Landscape Designation Review 2018 1.1. INTRODUCTION Statements of Importance. The Steering Group The present Area of Great Landscape Value (AGLV) have confirmed that the preferred name for local designation in Moray identified in the 2015 Local landscape designations in Moray is Special Development Plan has no background Landscape Area (SLA). documentation recording the reasons for 2 designation. Considerable change has also 1.3 STAGE ONE EVALUATION occurred to the character of some parts of the A review has been undertaken of landscape AGLV since it was first designated as wind farms character based on consideration of the revised and other built development is now SNH landscape character assessment for Moray, accommodated within, and close-by, these the 2016 Moray Wind Energy Landscape Capacity landscapes. Scottish Planning Policy (SPP) Study (MWELCS) and settlement capacity studies requires local authorities to identify and protect undertaken by Alison Grant for Forres, Fochabers, locally designated areas and to clearly explain the Lossiemouth and Elgin. This review has reasons for their designation. The key additionally been informed by the consultant’s requirements of this study are therefore to knowledge of Moray’s landscapes and has consider afresh areas of local landscape value resulted in the identification of 32 landscape with the aim of safeguarding and enhancing their character units for assessment (Figure 1). -

Advisory Visit River Isla October 2014

Advisory Visit River Isla October 2014 1.0 Introduction This report is the output of a site visit undertaken by Tim Jacklin of the Wild Trout Trust to the River Isla on 3rd October, 2014. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visit and discussions with Richie Miller of the Deveron, Bogie and Isla Rivers Trust (DBIT www.deveron.org) and Marcus Walters of the Moray Firth Trout Initiative (MFTI www.morayfirthtrout.org). Normal convention is applied throughout the report with respect to bank identification, i.e. the banks are designated left hand bank (LHB) or right hand bank (RHB) whilst looking downstream. 2.0 Catchment / Fishery Overview The River Isla is a tributary of the River Deveron, which flows northwards into the Moray Firth at Banff on the north coast of Aberdeenshire. The River Isla rises at Drummuir and flows north through the town of Keith, then west to its confluence with the Deveron close to Milltown of Rothiemay. The DBIT website www.deveron.org contains detailed information on the wider Deveron catchment, including a comprehensive fisheries management plan. Approximately 8km of the upper Isla was inspected during this walkover survey, between the junction of the Towie Burn (National Grid Reference (NGR) NJ3942045530) and Keith (NGR NJ4284750855), plus a short section at Drummuir station (NGR NJ3784244230). Land use in this area was predominantly mixed livestock and arable farming, with forestry on higher ground. Keith is home to a number of distilleries which abstract water from the Isla for cooling purposes; a number of weir structures which represent obstructions to free fish migration are associated with these abstraction points. -

Association of Salmon Fishery Boards

Association of Salmon Fishery Boards 2009 ANNUAL REVIEW Chairman’s Introduction HUGH CAMPBELL ADAMSON It gives me great pleasure to welcome you to the Association of Salmon Fishery Boards’ fi rst Annual Review. Its purpose is to inform and, I hope, to entertain - offering articles on various aspects of salmon and sea trout, together with river reports from 2008. Migratory fi sh are a wonderfully iconic asset to Scotland. They produce revenue, employment and pleasure to thousands, and in many areas are a key contributor to the rural economy. Yet for many years we took them for granted and relied on Mother Nature to ensure their annual return. While these halcyon days have gone, due primarily to increased mortality in the oceans, we have now learnt to encourage these phenomenal fi sh to prosper within our shores. It is over 150 years since two acts of Parliament created the framework for our unique management system, but the District Boards have stood the test of time. They have evolved from policing organisations to ones focused on conservation and management - usually working in conjunction with local Fisheries Trusts. We have commissioned the following articles with care and hope they give a balanced view of the current fi sheries climate in Scotland. They demonstrate the latest research and practical projects, highlight key threats posed to salmon, give an overview of last season, and also offer an international perspective. If you wish to make any comments HUGH CAMPBELL ADAMSON ANDREW WALLACE or observations we would be very pleased to hear from you. I would like to express our thanks to Strutt & Parker, without whose support this Review could not exist; to the contributors for their excellent articles; to the Fishmongers’ Company, who have been so supportive of the Association over recent years; and fi nally to those who read this and thereby continue to demonstrate an essential interest in Scottish salmon angling and management.