A Patchwork of Our Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainment & Syndication Fitch Group Hearst Health Hearst Television Magazines Newspapers Ventures Real Estate & O

hearst properties WPBF-TV, West Palm Beach, FL SPAIN Friendswood Journal (TX) WYFF-TV, Greenville/Spartanburg, SC Hardin County News (TX) entertainment Hearst España, S.L. KOCO-TV, Oklahoma City, OK Herald Review (MI) & syndication WVTM-TV, Birmingham, AL Humble Observer (TX) WGAL-TV, Lancaster/Harrisburg, PA SWITZERLAND Jasper Newsboy (TX) CABLE TELEVISION NETWORKS & SERVICES KOAT-TV, Albuquerque, NM Hearst Digital SA Kingwood Observer (TX) WXII-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ La Voz de Houston (TX) A+E Networks Winston-Salem, NC TAIWAN Lake Houston Observer (TX) (including A&E, HISTORY, Lifetime, LMN WCWG-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ Local First (NY) & FYI—50% owned by Hearst) Winston-Salem, NC Hearst Magazines Taiwan Local Values (NY) Canal Cosmopolitan Iberia, S.L. WLKY-TV, Louisville, KY Magnolia Potpourri (TX) Cosmopolitan Television WDSU-TV, New Orleans, LA UNITED KINGDOM Memorial Examiner (TX) Canada Company KCCI-TV, Des Moines, IA Handbag.com Limited Milford-Orange Bulletin (CT) (46% owned by Hearst) KETV, Omaha, NE Muleshoe Journal (TX) ESPN, Inc. Hearst UK Limited WMTW-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME The National Magazine Company Limited New Canaan Advertiser (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) WPXT-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME New Canaan News (CT) VICE Media WJCL-TV, Savannah, GA News Advocate (TX) HEARST MAGAZINES UK (A+E Networks is a 17.8% investor in VICE) WAPT-TV, Jackson, MS Northeast Herald (TX) VICELAND WPTZ-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, NY Best Pasadena Citizen (TX) (A+E Networks is a 50.1% investor in VICELAND) WNNE-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, -

708 Main Street, Houston, Texas

708 Main Street, Houston, Texas View this office online at: https://www.newofficeamerica.com/details/serviced-offices-708-main-street-h ouston-texas Spanning 10 floors, this fantastic business centre provides a friendly atmosphere for you to work alongside like- minded professionals and watch your business thrive. Choose from a diverse selection of hot desks and dedicated spaces, all of which are flooded with natural light and radiate contemporary elegance. Suites are fully furnished and equipped with state-of-the-art technology while boasting a unique wellness room which is ideal for meditation or prayer. Enjoy plenty of professional support and service from the experienced staff and the superb team room and conference rooms allow you to entertain potential clients in style. Transport links Nearest road: Nearest airport: Key features Access to multiple centres nation-wide Access to multiple centres world-wide Administrative support Bike racks Board room Car parking spaces Comfortable lounge Conference rooms Furnished workspaces High-speed internet Hot desking Kitchen facilities Meeting rooms Office cleaning service On-site management support Photocopying available Town centre location Unbranded offices WC (separate male & female) Wireless networking Location Nestled in the heart of Downtown Houston, this business centre commands spectacular views across the skyline and the Buffalo Bayou. Enjoy walking distance to a multitude of cultural amenities that are rich with vibrancy, including various performing arts centres, restaurants, bars and hotels which are ideal for treating clients to a night out. With Central Station Main stop right on the doorstep and several bus and tram stops nearby, there is unrivalled connectivity with the rest of the city and George Bush Intercontinental Airport can be reached within a 25 minute commute. -

Bayou Place Houston, Texas

Bayou Place Houston, Texas Project Type: Commercial/Industrial Case No: C031001 Year: 2001 SUMMARY A rehabilitation of an obsolete convention center into a 160,000-square-foot entertainment complex in the heart of Houston’s theater district. Responding to an international request for proposals (RFP), the developer persevered through development difficulties to create a pioneering, multiuse, pure entertainment destination that has been one of the catalysts for the revitalization of Houston’s entire downtown. FEATURES Rehabilitation of a "white elephant" Cornerstone of a downtown-wide renaissance that has reintroduced nighttime and weekend activity Maximized leasable floor area to accommodate financial pro forma requirements Bayou Place Houston, Texas Project Type: Adaptive Use/Entertainment Volume 31 Number 01 January-March 2001 Case Number: C031001 PROJECT TYPE A rehabilitation of an obsolete convention center into a 160,000-square-foot entertainment complex in the heart of Houston’s theater district. Responding to an international request for proposals (RFP), the developer persevered through development difficulties to create a pioneering, multiuse, pure entertainment destination that has been one of the catalysts for the revitalization of Houston’s entire downtown. SPECIAL FEATURES Rehabilitation of a "white elephant" Cornerstone of a downtown-wide renaissance that has reintroduced nighttime and weekend activity Maximized leasable floor area to accommodate financial pro forma requirements DEVELOPER The Cordish Company 601 East Pratt Street, Sixth Floor Baltimore, Maryland 21202 410-752-5444 www.cordish.com ARCHITECT Gensler 700 Milam Street, Suite 400 Houston, Texas 77002 713-228-8050 www.gensler.com CONTRACTOR Tribble & Stephens 8580 Katy Freeway, Suite 320 Houston, Texas 77024 713-465-8550 www.tribblestephens.com GENERAL DESCRIPTION Bayou Place occupies the shell of the former Albert Thomas Convention Center in downtown Houston’s theater district. -

North America CANADA

North America CANADA Gallons Guzzled 17.49 Gal Per Person Per Year Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Alberta Calgary Big Rock Brewery McNally's Ale Dec-01 15.5 5.0% Gary B. www.bigrockbeer.com Cold Cock Winter Porter May-09 17.0 Gary B. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site British Columbia Pacific Western Brewing Prince George Bulldog Canadian Lager May-09 16.0 Helen B. Company Vancouver Molson Breweries Molson Canadian Lager May-05 17.0 5.0% Helen B. Vancouver Island Brewing Vancouver Piper's Pale Ale May-09 16.0 Helen B. Company Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Manitoba Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site New Brunswick Saint John Moosehead Brewery Moosehead Lager Jul-01 17.0 5.1% Gary B. Moosehead Light Lager Sep-09 15.0 4.8% Maurice S. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site New Foundland St. John's Labatt Brewing Company Budweiser Lager Sep-02 18.0 5.0% Gary B. Bud Light Lager Sep-02 16.0 4.0% Gary B. St. John's Molson Brewery L.T.D. Black Horse Lager Sep-02 18.5 5.0% Gary B. Molson Canadian Lager Sep-09 17.5 5.0% Maurice S. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Northwest Territories Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Nova Scotia Halifax Labatt Brewing Company Labatt's Blue Pilsner Set-02 16.0 4.3% Maurice S. -

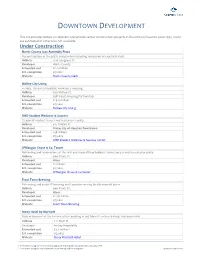

Downtown Development Project List

DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT This list provides details on all public and private sector construction projects in Downtown Houston since 1995. Costs are estimated or otherwise not available. Under Construction Harris County Jury Assembly Plaza Reconstruction of the plaza and pavilion including relocation of electrical vault. Address 1210 Congress St. Developer Harris County Estimated cost $11.3 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Harris County Clerk McKee City Living 4‐story, 120‐unit affordable‐workforce housing. Address 626 McKee St. Developer Gulf Coast Housing Partnership Estimated cost $29.9 million Est. completion 4Q 2021 Website McKee City Living UHD Student Wellness & Success 72,000 SF student fitness and recreation facility. Address 315 N Main St. Developer University of Houston Downtown Estimated cost $38 million Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website UHD Student Wellness & Success Center JPMorgan Chase & Co. Tower Reframing and renovations of the first and second floor lobbies, tunnel access and the exterior plaza. Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website JPMorgan Chase & Co Tower Frost Town Brewing Reframing and 9,100 SF brewing and taproom serving locally inspired beers Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2.58 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Frost Town Brewing Moxy Hotel by Marriott Redevelopment of the historic office building at 412 Main St. into a 13‐story, 119‐room hotel. Address 412 Main St. Developer InnJoy Hospitality Estimated cost $4.4 million P Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website Moxy Marriott Hotel V = Estimated using the Harris County Appriasal Distict public valuation data, January 2019 P = Estimated using the City of Houston's permitting and licensing data Updated 07/01/2021 Harris County Criminal Justice Center Improvement and flood damage mitigation of the basement and first floor. -

Women in Sports Presented by the University of Houston Friends of Women's Studies the Barbara Karkabi Living

Women In Sports Presented by The University of Houston Friends of Women’s Studies The Barbara Karkabi Living Archives Series April 13, 2016 Panel Biographies Tai Dillard is Assistant Women’s Basketball Coach at the University of Houston. She was born and raised in San Antonio, Texas. She played collegiate basketball and graduated from the University of Texas at Austin. The highlight of her college career was playing in the NCAA Women’s Final Four in 2003. After playing collegiately, Tai played in the WNBA for the San Antonio Silver Stars for 3 years, and also played professional basketball overseas in the Israeli Premier Basketball League in Tel Aviv, Israel. Once her playing career was over, Tai began coaching at her alma mater, Sam Houston High School where she coached crosscountry, basketball and track. In 2007 she began coaching collegiately at the University of Texas at San Antonio. During her time there she was a part of two Southland Conference Tournament Championships and one Southland Conference Championship. Following UTSA, Tai had coaching stops at the University of Southern California and The University of Mississippi before coming to the University of Houston. Debbie FergusonMcKenzie is the women’s sprints and hurdles coach for the Track and Field Program at the University of Houston. Debbie was born and raised in the Bahamas, and attended the University of Georgia, where she was an NCAA champion before graduating in 1999. Debbie is a tentime Bahamas national champion in the 100 and 200 meter sprints. She was awarded the Austin Sealy Trophy for the most outstanding athlete of the 1995 CARIFTA Games. -

SUMMARY PLAN DESCRIPTION the Hearst Corporation Retirement Plan Contents

SUMMARY PLAN DESCRIPTION The Hearst Corporation Retirement Plan Contents THE HEARST CORPORATION RETIREMENT PLAN................................................................................1 LIFE EVENTS AND THE RETIREMENT PLAN...........................................................................................2 IMPORTANT DEFINITIONS.........................................................................................................................3 WHEN PARTICIPATION BEGINS ...............................................................................................................5 TRANSFERS.................................................................................................................................................6 CREDITED SERVICE AND VESTING SERVICE ........................................................................................6 IF YOU BECOME DISABLED...........................................................................................................................6 IF YOU TAKE AN APPROVED LEAVE OF ABSENCE...........................................................................................7 IF YOU TAKE A MILITARY LEAVE OF ABSENCE ...............................................................................................7 WHEN YOU DO NOT EARN CREDITED SERVICE.............................................................................................7 SPECIAL VESTING........................................................................................................................................7 -

30Th Anniversary of the Center for Public History

VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2015 HISTORY MATTERS 30th Anniversary of the Center for Public History Teaching and Collection Training and Research Preservation and Study Dissemination and Promotion CPH Collaboration and Partnerships Innovation Outreach Published by Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 28½ Years Marty Melosi was the Lone for excellence in the fields of African American history and Ranger of public history in our energy/environmental history—and to have generated new region. Thirty years ago he came knowledge about these issues as they affected the Houston to the University of Houston to region, broadly defined. establish and build the Center Around the turn of the century, the Houston Public for Public History (CPH). I have Library announced that it would stop publishing the been his Tonto for 28 ½ of those Houston Review of History and Culture after twenty years. years. Together with many others, CPH decided to take on this journal rather than see it die. we have built a sturdy outpost of We created the Houston History Project (HHP) to house history in a region long neglectful the magazine (now Houston History), the UH-Oral History of its past. of Houston, and the Houston History Archives. The HHP “Public history” includes his- became the dam used to manage the torrent of regional his- Joseph A. Pratt torical research and training for tory pouring out of CPH. careers outside of writing and teaching academic history. Establishing the HHP has been challenging work. We In practice, I have defined it as historical projects that look changed the format, focus, and tone of the magazine to interesting and fun. -

CITY of HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Melrose Building AGENDA ITEM: C OWNERS: Wang Investments Networks, Inc. HPO FILE NO.: 15L305 APPLICANT: Anna Mod, SWCA DATE ACCEPTED: Mar-02-2015 LOCATION: 1121 Walker Street HAHC HEARING DATE: Mar-26-2015 SITE INFORMATION Tracts 1, 2, 3A & 16, Block 94, SSBB, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. The site includes a 21- story skyscraper. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY The Melrose Building is a twenty-one story office tower located at 1121 Walker Street in downtown Houston. It was designed by prolific Houston architecture firm Lloyd & Morgan in 1952. The building is Houston’s first International Style skyscraper and the first to incorporate cast concrete cantilevered sunshades shielding rows of grouped windows. The asymmetrical building is clad with buff colored brick and has a projecting, concrete sunshade that frames the window walls. The Melrose Building retains a high degree of integrity on the exterior, ground floor lobby and upper floor elevator lobbies. The Melrose Building meets Criteria 1, 4, 5, and 6 for Landmark designation of Section 33-224 of the Houston Historic Preservation Ordinance. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE Location and Site The Melrose Building is located at 1121 Walker Street in downtown Houston. The property includes only the office tower located on the southeastern corner of Block 94. The block is bounded by Walker Street to the south, San Jacinto Street to the east, Rusk Street to the north, and Fannin Street to the west. The surrounding area is an urban commercial neighborhood with surface parking lots, skyscrapers, and multi-story parking garages typical of downtown Houston. -

Houston Chronicle Index to Mexican American Articles, 1901-1979

AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE This index of the Houston Chronicle was compiled in the Spring and summer semesters of 1986. During that period, the senior author, then a Visiting Scholar in the Mexican American Studies Center at the University of Houston, University Park, was engaged in researching the history of Mexican Americans in Houston, 1900-1980s. Though the research tool includes items extracted for just about every year between 1901 (when the Chronicle was established) and 1970 (the last year searched), its major focus is every fifth year of the Chronicle (1905, 1910, 1915, 1920, and so on). The size of the newspaper's collection (more that 1,600 reels of microfilm) and time restrictions dictated this sampling approach. Notes are incorporated into the text informing readers of specific time period not searched. For the era after 1975, use was made of the Annual Index to the Houston Post in order to find items pertinent to Mexican Americans in Houston. AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE by Arnoldo De Leon and Roberto R. Trevino INDEX THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE October 22, 1901, p. 2-5 Criminal Docket: Father Hennessey this morning paid a visit to Gregorio Cortez, the Karnes County murderer, to hear confession November 4, 1901, p. 2-3 San Antonio, November 4: Miss A. De Zavala is to release a statement maintaining that two children escaped the Alamo defeat. History holds that only a woman and her child survived the Alamo battle November 4, 1901, p. -

Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter As Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Seeing and Then Seeing Again: Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter as Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J. Bellocq and George Valentine Dureau A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Timothy J. Lithgow December 2019 Thesis Committee: Dr. Johannes Endres, Co-Chairperson Dr. Elizabeth W. Kotz, Co-Chairperson Dr. Keith M. Harris Copyright by Timothy J. Lithgow 2019 The Thesis of Timothy J. Lithgow is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements: Thank you to Keith Harris for discussing George Dureau on the first day of class, and for all his help since then. Thank you to Liz Kotz for conveying her clear love of Art History, contemporary arts and artists. Although not on my committee, thank you to Jeanette Kohl, for her thoughtful and nuanced help whenever asked. And last, but certainly not least, a heartfelt thank you to Johannes Endres who remained calm when people talked out loud during the quiz, who had me be his TA over and over, and who went above and beyond in his role here. iv Dedication: For Anita, Aubrey, Fiona, George, Larry, Lillian, Myrna, Noël and Paul. v Table of Contents Excerpt from Pentimento by Lillian Hellman ......................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: Biographical Information for Dureau and Bellocq .......................... 18 Table 1 ...................................................................................................... 32 Excerpt from One Arm by Tennessee Williams.................................................... 34 Chapter 2: Colonial Foundations of Libertine Tolerance in New Orleans, LA .. -

Luis De Unzaga and Bourbon Reform in Spanish Louisiana, 1770--1776

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Luis De Unzaga and Bourbon Reform in Spanish Louisiana, 1770--1776. Julia Carpenter Frederick Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Frederick, Julia Carpenter, "Luis De Unzaga and Bourbon Reform in Spanish Louisiana, 1770--1776." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7355. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7355 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.