"Roseanne" and "Murphy Brown"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

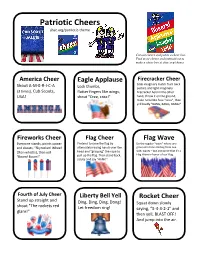

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

EMPOWERMENT JOURNAL Gogo Bebe Great!Great!

EMPOWERMENT JOURNAL GoGo BeBe Great!Great! 10-WEEK SAMPLE (Learn more about the full 40-week journal at www.BelieveInYou.com) NAME SCHOOL GRADE Your personal empowerment story. Choose how to share your greatness! EMPOWERMENT /noun/ The process of becoming stronger and more confident, especially in controlling one’s life and claiming one’s rights. STUDENTS HAVE THE RIGHT TO… • live optimistically. • act on positive motivation. • live with respect for self and others. • communicate with a unique voice. • make choices about how to share their greatness. THIS IS YOUR STORY Go Be Great! “Reach high, for the stars lie hidden in your soul.” – Langston Hughes What is an empowerment journal? This journal is your guide to unlocking greatness. Within every living thing there is greatness, and every example of greatness is unique. Your greatness must look different from someone else’s greatness.The world depends on this uniqueness. On the pages of this journal, you will discover the gifts you bring with you each and every day. You’ll build the confidence and skills that you’ll use to unlock your greatness. You will build self-awareness skills, like recognizing and discussing your emotions. You’ll learn self-management strategies that will help you stay motivated and focused. You will think about social awareness as you work to respect the unique greatness of your classmates and friends. You’ll work to build trusting relationships with positive communication and encouraging words. And you will practice decision-making that will allow you to share your greatness with the world. This work won’t be easy. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

General Cheers

NWA Kickball Cheers General Cheers Alamo: Kick it high. Kick it low. Kick it to the Alamo. Alamo, here we come. __________ is number one! Hot Dog: __________ wants a hot dog. __________ wants a coke. __________ wants a Home Run, and that's no joke! __________ wants a an orange. __________ wants a shake. __________ wants a to make it to Home Plate! Rock You [ Stomp, stomp, clap. Stomp, stomp, clap. ] We will, we will … Rock you down. Shake you up. Like a volcano ready to erupt. Watch out world. Here we come. __________ is number one! Froggy There was a little froggy -- sitting on a log He rooted for the other team -- it made no sense at all. We pushed him the water, and bonked his little head. And when he came back up again, this is what he said, he said: Go! Go, go! Go, mighty __________ . Fight! Fight, fight! Fight, mighty __________ . Win! Win, win! Win, mighty __________ . Go! Fight! WIn! Beat 'em till the end. Wooo! Big We’re BIG - B. I. G. And we’re BAD - B. A. D. And we’re BOSS - B. O. S. S. - B. O. S. S. - BOSS ! (REPEAT) We Are We are the __________ . Couldn't be prouder. If you can't hear us, we'll yell a little louder. (REPEAT - Louder each time) Stand Up Two bits! Four bits! Six bits! A dollar! All for the __________ stand up and holler! Call & Answer Cheers Dynamite: Our team is WHAT? DYNAMITE! Our team is WHAT? DYNAMITE! Our team is -- Hold on. -

Rock Has Risen

FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 24, 2018 5:28:59 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of April 1 - 7, 2018 Rock has risen John Legend as seen in “Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 The last days of Christ get rock star treatment in an all-new, live televised musical production. With John Legend (“La La Land,” 2016) as Jesus, Sara Bareilles as Mary Magdalene and hard rock legend Alice Cooper as King Herod, Easter Sunday has never been so loud. Enjoy a fresh take on a tale of biblical proportions when “Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert” airs Sunday, April 1, on NBC. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL Salem, NH • Derry, NH • Hampstead, NH • Hooksett, NH ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE Newburyport, MA • North Andover, MA • Lowell, MA ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 YOUR MEDICAL HOME FOR CHRONIC ASTHMA Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE SPRING ALLERGIES ARE HERE! 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE 1 x 3” DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN INSPECTIONS Alleviate your mold allergy this season! We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC Appointments Available Now CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 978-683-4299 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA www.newenglandallergy.com at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Thomas F. -

Rebooting Roseanne: Feminist Voice Across Decades

Home > Vol 21, No 5 (2018) > Ford Rebooting Roseanne: Feminist Voice across Decades Jessica Ford In recent years, the US television landscape has been flooded with reboots, remakes, and revivals of “classic” nineties television series, such as Full/er House (1987-1995, 2016- present), Will & Grace (1998-2006, 2017-present), Roseanne (1988-1977, 2018), and Charmed (1998-2006, 2018-present). The term “reboot” is often used as a catchall for different kinds of revivals and remakes. “Remakes” are derivations or reimaginings of known properties with new characters, cast, and stories (Loock; Lavigne). “Revivals” bring back an existing property in the form of a continuation with the same cast and/or setting. “Revivals” and “remakes” both seek to capitalise on nostalgia for a specific notion of the past and access the (presumed) existing audience of the earlier series (Mittell; Rebecca Williams; Johnson). Reboots operate around two key pleasures. First, there is the pleasure of revisiting and/or reimagining characters that are “known” to audiences. Whether continuations or remakes, reboots are invested in the audience’s desire to see familiar characters. Second, there is the desire to “fix” and/or recuperate an earlier series. Some reboots, such as the Charmed remake attempt to recuperate the whiteness of the original series, whereas others such as Gilmore Girls: A Life in the Year (2017) set out to fix the ending of the original series by giving audiences a new “official” conclusion. The Roseanne reboot is invested in both these pleasures. It reunites the original cast for a short-lived, but impactful nine-episode tenth season. -

HIV/AIDS Let's Talk About It: Prevention

HIV/AIDS Let’s Talk About It: Prevention and Awareness in the Community May Nealey Tinsley Elementary School INTRODUCTION HIV/AIDS may seem like an irrelevant subject for elementary students; however, I am fully convinced that not only is it a subject that needs to be taught to that age group, but that it must be implemented now. Take a moment to look at our culture today. We are exposing our young children to sexual activity at increasingly younger ages. We need look no further than the family television set to see the cultural changes that have taken place in the last few years. In the 1960s, Hugh Beaumont could only give Barbara Billingsley a chaste kiss on the cheek in any room in the house except the bedroom on the popular sitcom, Leave It to Beaver. Single parent, Fred MacMurray, on the popular series, My Three Sons, would have never asked his lady friend to spend the night or live with him without the benefit of marriage. In our culture today we see married couples in bed together in sexually implicit scenes that leave little to the imagination on both daytime and nighttime television. We see single couples, both heterosexual and homosexual, living together openly. Shows like Will & Grace and Ellen have done much to change the attitudes of the average American as to what can and cannot be shown on national television. Even with these groundbreaking shows, polls show that 55% of Americans still disapprove of same sex marriage (Pew Forum). A Gallup Poll conducted in 2002 shows that 51% of Americans are married, 6% live with a partner, 9% are widowed, 14% are separated or divorced, and 18% never married.