Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Colours Part 1: the Regular Battalions

The Colours Part 1: The Regular Battalions By Lieutenant General J. P. Riley CB DSO PhD MA FRHistS 1. The Earliest Days At the time of the raising of Lord Herbert’s Regiment in March 1689,i it was usual for a regiment of foot to hold ten Colours. This number corre- sponded to the number of companies in the regiment and to the officers who commanded these companies although the initial establishment of Herbert’s Regiment was only eight companies. We have no record of the issue of any Colours to Herbert’s Regiment – and probably the Colo- nel paid for their manufacture himself as he did for much of the dress and equipment of his regiment. What we do know however is that each Colour was the rallying point for the company in battle and the symbol of its esprit. Colours were large – generally six feet square although no regulation on size yet existed – so that they could easily be seen in the smoke of a 17th Century battlefield for we must remember that before the days of smokeless powder, obscuration was a major factor in battle. So too was the ability of a company to keep its cohesion, deliver effec- tive fire and change formation rapidly either to attack, defend, or repel cavalry. A company was made up of anywhere between sixty and 100 men, with three officers and a varying number of sergeants, corporals and drummers depending on the actual strength. About one-third of the men by this time were armed with the pike, two-thirds with the match- lock musket. -

Regimental Associations

Regimental Associations Organisation Website AGC Regimental Association www.rhqagc.com A&SH Regimental Association https://www.argylls.co.uk/regimental-family/regimental-association-3 Army Air Corps Association www.army.mod.uk/aviation/ Airborne Forces Security Fund No Website information held Army Physical Training Corps Assoc No Website information held The Black Watch Association www.theblackwatch.co.uk The Coldstream Guards Association www.rhqcoldmgds.co.uk Corps of Army Music Trust No Website information held Duke of Lancaster’ Regiment www.army.mod.uk/infantry/regiments/3477.aspx The Gordon Highlanders www.gordonhighlanders.com Grenadier Guards Association www.grengds.com Gurkha Brigade Association www.army.mod.uk/gurkhas/7544.aspx Gurkha Welfare Trust www.gwt.org.uk The Highlanders Association No Website information held Intelligence Corps Association www.army.mod.uk/intelligence/association/ Irish Guards Association No Website information held KOSB Association www.kosb.co.uk The King's Royal Hussars www.krh.org.uk The Life Guards Association No website – Contact [email protected]> The Blues And Royals Association No website. Contact through [email protected]> Home HQ the Household Cavalry No website. Contact [email protected] Household Cavalry Associations www.army.mod.uk/armoured/regiments/4622.aspx The Light Dragoons www.lightdragoons.org.uk 9th/12th Lancers www.delhispearman.org.uk The Mercian Regiment No Website information held Military Provost Staff Corps http://www.mpsca.org.uk -

Urbanisation, Elite Attitudes and Philanthropy: Cardiff, 1850–1914

NEIL EVANS URBANISATION, ELITE ATTITUDES AND PHILANTHROPY: CARDIFF, 1850-1914* How did philanthropy adjust to the transformation of society in the nineteenth century? What was its role in social relations and in relieving poverty? Recent writers studying these issues have suggested the need for detailed studies at local level, and in studying some English towns and cities in the earlier part of the nineteenth century they have come to varying conclusions. Roger Smith's study of Nottingham shows that philanthropy added insignificantly to the amount of relief available through the Poor Law.1 By contrast Peter Searby's study of Coventry shows that philanthropic funds were quite abundant and after some reforms in the 1830's even applied to the relief of the poor!2 Professor McCord's articles on the North-East of England in the early nineteenth century seek to establish the more ambitious claim "that nineteenth-century philanthropy provided increasing resources and extended machinery with which to diminish the undesirable effects of that period's social problems".3 As yet, there has been no attempt to study philanthropic provision in a newly developing town without an industrial tradition in the late nineteenth century. Professor McCord recognises that charitable effort became less appropriate in the "much more complicated and sophisticat- ed" society of the late nineteenth century, but he does not analyse the * I would like to thank Martin Daunton, Jon Parry, Michael Simpson, Peter Stead, John Williams and the editors of this journal for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, and Non Jenkins for her help in locating some uncatalogued material in the National Library of Wales. -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON 'GAZETTE, 21 DECEMBER, 1944 5853 No

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON 'GAZETTE, 21 DECEMBER, 1944 5853 No. 4694089 Private Eric Bullen Holmes, The War Office, list December, 1944. King's Own Yorkshire Ligiht Infantry (Guiseley). The KING has been graciously pleased to approve No. 6209862 Sergeant Douglas Arthur Batchelor, the following awards in recognition of gallant and The Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge's distinguished services in North West Europe: — Own) (Annan). Jfo. 5567194 Sergeant John Gridley, The Wiltshire Bar to the Distinguished Service Order. Regiment (Duke of Edinburgh's) (Luton). No. 5044452 Private George Dale, The North Major (temporary Lieutenant.-Colonel) Denis Lucius Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's) Alban Gibbs, D.S.O. (34771), The Queen's Royal (Stoke-on-Trent). Regiment (West Surrey) (Hatfield). No. 5947792 Warrant Officer Class II (Company Major (temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) John Adam Sergeant-Major) Arthur Mattin, The Durham Hopwood, D.S.O. (44885), The Black Watch Light Infantry. (Royal Highland Regiment) (St. Andrews). No. 595.1910 Sergeant Peter William Hamilton Captain (temporary Major) George Willoughby Dunn, Griffin, The Durham Light .Infantry (High D.S.O., M.C. (65906), The Black Watch (Royal Cross, Herts). 'Highland Regiment) (Glasgow, W.2). No. 4345247 Sergeant Harold Wilmott, Army Air Major (temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) John Herbert Corps (Rotherham). Walford, D.S.O. (14776), The Seaforth Highlanders No. 6096731 Corporal (acting Sergeant) Jack Barter, (Ross-shire Buffs, The Duke of Albany's) (Basing- Army Air Corps ((London, N.g). stoke). No. S/57901 Staff-Sergeant Edwin John Hughes, The Distinguished Service Order. Royal Army Service Corps (Chester). Major Peter Pettit (51848), Royal Horse Artillery No. -

EX 1 KINGS (1952-1954) Norman Passed Away on Wednesday 25Th April 2012, Aged 78

Page 1 The King’s Regiment Association Liverpool Branch A Branch of the Duke of Lancaster’s Regimental Association Nec Aspera Terrent’ JJUUNNEE 22001122 NNEEWWSSLLEETTTTEERR –– IISSSSUUEE 3322 EELLEECCTTRROONNIICC EEDDIITTIIOONN <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> DONATIONS TO THE ASSOCIATION The Committee would like to thank the following who have made a cash donation to the general association funds: MR DAVID FACHIRI, MRS MARGRETE MOORE YOUR GENEROSITY IS VERY MUCH APPRECIATED. <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> <> Colonel Chris Owen took up his appointment as Regimental Secretary The Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment effective from Monday 16th April 2012. Colonel Owen on a visit to the Liverpool Anglican Cathedral (26th April 2012) Page 2 We require your letters, comments, photographs, stories etc for inclusion in the next Newsletter which will be published in: AUGUST 2012. The closing date for submission is: MMOONNDDAAYY 2233RRDD JJUULLYY Please forward to: Eric Roper 171 Queens Drive Liverpool L18 1JP email: [email protected] I can scan photographs and return the originals, but please provide a SAE. Please enclose a detailed description, ie, names, dates etc of any photograph(s). ‘100’ CLUB The APRIL 2012 draw was made at City Office, Liverpool on Tuesday 4th April 2012 by Committee member Major E McMahon & the winner is: 1ST PRIZE (£50) MR W SEFTON The MAY 2012 draw was made at Townsend Avenue TAC, Liverpool on Friday 25th May 2012 by Korean Veteran Terry Clarke, & the winner is: 1ST PRIZE (£50) MR R WAIT Please be advised that the July quarterly committee meeting scheduled for 1130 hrs 15th July 2012 at Townsend TAC has been cancelled. The July quarterly committee meeting will now take place at Walker House, Liverpool on Tuesday 3rd July 2012 at 1200 hrs. -

XXX Corps Operation MARKET-GARDEN 17 September 1944

British XXX Corps Operation MARKET-GARDEN 17 September 1944 XXX Corps DUTCH-BELGIUM BORDER 17 September 1944 ANNEX A: Task Organization to Operation GARDEN XXX Corps LtGen Brian G. HORROCKS Guards Armoured Division Brig Allan H. S. ADAIR 43rd Wessex Division MajGen G. I. THOMAS 50th Northumberland Division MajGen D. A. H. GRAHAM 8th Armoured Brigade Brig Erroll G. PRIOR-PALMER Princess Irene (Royal Netherlands) BrigadeCol Albert “Steve” de Ruyter von STEVENICK Royal Artillery 64th Medium Regiment R.A. 73rd AT Regiment R.A. 27th LAA Regiment R.A. 11th Hussars Sherman tanks of British XXX Corps advance across the bridge at Nijmegen during MARKET-GARDEN. 1 Guards Armoured Division Operation MARKET-GARDEN 17 September 1944 Guards Armoured Division DUTCH-BELGIUM BORDER 17 September 1944 ANNEX A: Task Organization to Operation GARDEN Guards Armoured Division Brig Allan H. S. ADAIR Promoted MajGen ADAIR on 21 Sep 1944 5th Guards Armoured Brigade 2nd Bn, Grenadier Guards (Armor) 1st Bn, Grenadier Guards (Mot) LtCol Edward H. GOULBURN 2nd Bn, Irish Guards (Armor) LtCol Giles VANDELEUR + 3rd Bn, Irish Guards, 32nd Guards Brigade (Mot) LtCol J. O. E. “Joe” VANDELEUR 32nd Guards Infantry Brigade Brig G. F. JOHNSON + 1st Bn, Coldstream Guards, 5th Guards Brigade (Armor) 5th Bn, Coldstream Guards (Mot) 2nd Bn, Welsh Guards (Armor) 1st Bn, Welsh Guards (Mot) Royal Artillery 55th Field Regiment RA 153rd Field Regiment RA 21st AT Regiment RA 94th LAA Regiment + 1st Independent MG Company Royal Engineers 14th Field Squadron 615th Field Squadron 148th Field Park Squadron + 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment RAC XXX Corps Commander, LtGen Horrocks, ordered the Guards Armoured Division to form tank-infantry Battle Groups by pairing each Tank Battalion with an Infantry Battalion. -

RANKS) Part 14 Regulations Covering Standards, Guidons, Colours And

ARMY DRESS REGULATIONS (ALL RANKS) Part 14 Regulations covering Standards, Guidons, Colours and Banners of the British Army Ministry of Defence PS12(A) August 2013 SECTION 1 – GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION 14.01 Scope. These regulations contain the regulations dealing with the scale, provision, accounting, control, design and care of Standards, Guidons, Colours and Banners. 14.02 Application. These regulations are applicable to the Regular Army, the TA, the ACF and the CCF, and the MOD sponsored Schools. 14.03 Layout. These regulations is divided into the following Sections and related Annexes and Scales: Section 1 – General Instructions. Section 2 - Standards, Guidons and Colours. Annex A - Scales of issue of Standards, Guidons and Colours. Annex B - Pictorial Guide to designs of Standards, Guidons and Colours. Annex C - Badges, Devices, Distinctions and Mottoes borne on Standards, Guidons and Colours. Annex D - Company Badges borne on the Regimental Colours of the Guards Division. Annex E - Badges borne on the Regimental Colours of the Infantry. Annex F - Regimental Facing Colours. Annex G - Divisional Facing Colours. Section 3 - State Colours. a. Annex A - Full Description. Section 4 - RMAS Sovereign’s Banner, ACF and CCF Banners and DYRMS and QVS Banners. 14.04 Related Publications. These regulations should be read in conjunction with Queen’s Regulations (QRs) paras 8.019 to 8.032, Ceremonial for the Army AC 64332 and the Army List. Part 14 Sect 1 PROVISION, ACCOUNTING AND AINTENANCE 14.05 Provision and Accounting. Unless otherwise indicated, the items covered by these regulations are provided and maintained by DES. They are to be held on charge in the appropriate clothing account on AF H8500 (Clothing Account Sheet) as directed on the Unit clothing account database. -

Dead Men Risen: the Welsh Guards and the Defining Story of Britains War in Afghanistan Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DEAD MEN RISEN: THE WELSH GUARDS AND THE DEFINING STORY OF BRITAINS WAR IN AFGHANISTAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Toby Harnden | 400 pages | 27 Oct 2011 | Quercus Publishing | 9781849164238 | English | London, United Kingdom Dead Men Risen: The Welsh Guards and the Defining Story of Britains War in Afghanistan PDF Book The Welsh Guards were part of the 1st Guards Brigade and performed internal security IS duties while there, before leaving in during the British withdrawal and when the state of Israel was declared. Soon after the end of the war in the 1st Welsh Guards returned home and where they would be based for much of the inter-war period, performing training and ceremonial duties, such as the Changing of the Guard and Trooping the Colour. The London Gazette. Retrieved 29 April BBC News. Palace Barracks Memorial Garden. The attack on Sir Galahad culminated in high casualties, 48 dead, 32 of them Welsh Guards, 11 other Army personnel and five crewmen from Sir Galahad herself. It will alternate this role with the Grenadier Guards. They were involved in Operation Fresco , the British armed forces response to the firefighters strike ; the Welsh Guards covered the Midlands area, primarily in Birmingham using the antiquated Army Green Goddess fire engines. Bloody Heroes. Just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, 1st Welsh Guards were dispatched to Gibraltar where they remained upon the outbreak of war in September Recruits to the Guards Division go through a thirty-week grueling training programme at the Infantry Training Centre ITC and is one of the hardest basic training courses in the world and produces some of the best soldiers in the world. -

Welsh Guards Magazine 2011

WREGEIMLENSTAHL MGAGUAZAINRE 2D01S 1 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE 2011 COLONEL-IN-CHIEF Her Majesty The Queen COLONEL OF THE REGIMENT His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales KG KT GCB OM AK QSO PC ADC REGIMENTAL LIEUTENANT COLONEL Brigadier R H Talbot Rice REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Colonel (Retd) T C S Bonas BA ASSISTANT REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Major (Retd) K F Oultram * REGIMENTAL HEADQUARTERS Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk, London, SW1E 6HQ Contact Regimental Headquarters by Email: [email protected] View the Regimental Website at www.army.mod.uk/welshguards * AFFILIATIONS 5th/7th Battalion The Royal Australian Regiment HMS Campbeltown 1 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE CONTENTS FOREWORD WELSH GUARDS AFGHANISTAN APPEAL ADVERTISEMENTS ................................................ 95 Regimental Lieutenant Colonel ......................... 3 The Welsh Guards Afghanistan Appeal By The Commanding Officer WELSH GUARDS COLLECTION ................ 100 by Col Bonas ................................................................ 53 1st Bn Welsh Guards ................................................. 4 Charity Golf Day ......................................................... 57 WELSH GUARDS ASSOCIATION 1ST BATTALION WELSH GUARDS Ride of Respect ........................................................... 60 ASSOCIATION BRANCH REPORTS The Prince of Wales’s Company ........................ 5 Cardiff Branch .......................................................... 102 Number Two Company ........................................... 8 BATTLEFIELD -

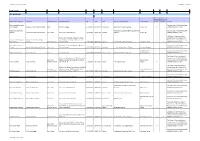

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

5906 Supplement to the London Gazette, 13 December, 1949

5906 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13 DECEMBER, 1949 CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE .ORDERS OF Brigadier (temporary) IN. D. RICE (5783), Buffs. KNIGHTHOOD. Brigadier (temporary) C. G. ROBINS (13950), late St. James's Palace, S.W.I. Y. & L. Brigadier (temporary) F. H. C. ROGERS, C.B.E.. December, 1949. D.S.O., M.C. (17114), late R.A. The RING has 'been graciously pleased to approve Colonel A. E. CAMPBELL (30235), late R.A.M.C. the award of the British Empire Medal (Military Division), in recognition of gallant and distinguished Employed List. services in Malaya during the period 1st January, Lieutenant-Colonel R. L. K. ALLEN, O.B.E. (6183). 1949, to 30th June, 1949, to the undermentioned:— ROYAL ARMOURED .CORPS. MYA/ 18019241 Warrant Officer Class I (acting) Royal Tank Regiment. ATTAM BIN YATIN, Royal Army Service Corps. Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary) S. P. WOOD 7662953 Staff Sergeant John Milner Buchanan (45005). BONELL, Royal Army Pay Corps. Major (temporary) S. P. M. SUTTON, M.C. (7702). 177853'! Sergeant Roy Victor CUDLIP, Corps of Royal Military (Police. 4th Queen's Own Hussars. 2814476 Sergeant Walter "Ross GRANT, The Seaforth Lieutenant-Colonel R. S. G. SMITH (44724). Highlanders ^Ross-shire IBuffs, The Duke of Captain (temporary) G. K. BIDIE (386204). Albany's). 553824 War Substantive/Sergeant J. STREET. 5334915 Staff Sergeant Joseph George HILLS, Royal 22202630 Trooper C. R. CARTER. Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. 14194104 Trooper J. H. GOODIER. 2702482 Corporal iFrank HOWARTH, Scots Guards. 19040839 Trooper K. GUY. 19042700 ^Lance-corporal Anthony Walter HURST, 21187657 Trooper R. E. PETERS. Royal Corps of Signals. -

Section 5 the Guards Division

SECTION 5 THE GUARDS DIVISION – OFFICERS INTRODUCTION Application. The regulations contained in this chapter apply to all officers of the Guards Division. Layout. This Section is divided into the following Chapters: Chapter 1 - Full Dress Chapter 2 - No 1 Dress Chapter 3 - No 2 Dress Chapter 4 - Mess Dress Chapter 5 - Other Orders of Dress UNIVERSAL ITEMS OF DRESS 03.5001. Cape. Milled Atholl grey cloth, lined Wellington red of length to cover the finger tips when the arms are held straight down and the fingers extended. A 3” deep turn down prussian type collar fastened with 2 hook and eye fastenings; 3 small gilt buttons below. The cape is cut in one piece with shoulder seams. 03.5002. Greatcoat. Milled Atholll grey cloth, lined with Wellington red, double-breasted to reach within a foot of the ground; 2 rows of gilt buttons of regimental pattern down the front, ending at the waist, 5 buttons in each row, the top ones 13” and the bottom pair 6” apart. 03.5003. Cap Badges. Regiment Cap Forage Peaked Cap Khaki Peaked Beret 1 (a) (b) (c) (d) A grenade in gold A grenade in gold A grenade in gold GREN GDS embroidery embroidery embroidery In silver plate the star of As for Forage Cap but The star of the Order the Order of the Garter. smaller. of the Garter in silver The Garter and motto in embroidery. COLDM GDS silver over Garter blue enamel; the cross in red enamel. In silver plate, the star of As for Forage Cap but Small star of the the Order of the Thistle; smaller.