Disrupting, Managing and Assembling Futures in Teesside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redcar and Cleveland

Redcar and Cleveland Personal Details: Name: Lynn Buckton E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Comment text: I have lived in Dormanstown for over 23 years. I moved here when my husband decided to come back home. My husband was born and lived all his chilhood in Dormanstown. Dormanstown was built for the workers of the steel industry. Also building some of the countries first retirement homes. It makes no sense to me as a resident why the steel work site is been removed from dormanstown. Whilst removing the industry from what is already a deprived and poor ward why would you want to do this as it will only make the ward poorer and less funds available when the industry goes so does any section 106 money which can only help and support the ward. id like to see the ward back with its heritage in tact and 3 ward councillors as i believe our ward is best represented with 3 rather than 2 which will make things harder for me as they will have a bigger work load and less support. Also as a member of friends of westfield farm we have used funding from the councillors on a number of occasions in order for us to put on events for the community. Our biggest been last year when we opened up the 100yrs celebrations and are continuing with this. this year. i am sure if i had the time to write a petition there would be a high percentage of the residents sign it. Yours Mrs L Buckton Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded Redcar and Cleveland Personal Details: Name: Jeremy Crow E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Feature Annotations 2: Transfer area east of line to Coatham or Dormanstown. -

Cleveland Naturalists'

CLEVELAND NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Volume 5 Part 1 Spring 1991 CONTENTS Recent Sightings and Casual Notes CNFC Recording Events and Workshop Programme 1991 The Forming of a Field Study Group Within the CNFC Additions to Records of Fungi In Cleveland Recent Sightings and Casual Notes CNFC Recording Events and Workshop Programme 1991 The Forming of a Field Study Group Within the CNFC Additions to Records of Fungi In Cleveland CLEVELAND NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB 111th SESSION 1991-1992 OFFICERS President: Mrs J.M. Williams 11, Kedleston Close Stockton on Tees. Secretary: Mrs J.M. Williams 11 Kedleston Close Stockton on Tees. Programme Secretaries: Misses J.E. Bradbury & N. Pagdin 21, North Close Elwick Hartlepool. Treasurer; Miss M. Gent 42, North Road Stokesley. Committee Members: J. Blackburn K. Houghton M. Yates Records sub-committee: A.Weir, M Birtle P.Wood, D Fryer, J. Blackburn M. Hallam, V. Jones Representatives: I. C.Lawrence (CWT) J. Blackburn (YNU) M. Birtle (NNU) EDITORIAL It is perhaps fitting that, as the Cleveland Naturalist's Field Club enters its 111th year in 1991, we should be celebrating its long history of natural history recording through the re-establishment of the "Proceedings". In the early days of the club this publication formed the focus of information desemmination and was published continuously from 1881 until 1932. Despite the enormous changes in land use which have occurred in the last 60 years, and indeed the change in geographical area brought about by the fairly recent formation of Cleveland County, many of the old records published in the Proceedings still hold true and even those species which have disappeared or contracted in range are of value in providing useful base line data for modern day surveys. -

Countryside Rights of Way Improvement Plan for the Next Five Years

SALTBURN AND DISTRICT BRIDLEWAYS GROUP Spring Newsletter 2016 Welcome to our spring newsletter. There’s never been a better time to be a member of the group – as well as exciting discounts for you, we have lots of exciting things coming up this year, including details of our ever popular pleasure ride and some great guests appearing at our public meetings. Five-year rights of way plan SADBG committee members met with Ian Tait, rights of way advisor for Redcar and Cleveland Council to discuss the area’s Countryside Rights of Way Improvement Plan for the next five years. Members were asked to produce a "wish list" which was presented to Ian, this included: Black Ash Path to St Germain’s, Marske – Split into a bridleway and a footpath? Errington Woods permissive bridleway - status change to public bridleway (formal application submitted by SADBG last year) Convert the track between the footpath and bridleway in Errington Woods into bridleway to make a loop round Pontac Road and Quarry Lane. Footpaths from Gurney Street, New Marske, to Catt Flatt Lane converted to bridleways to link with Green Lane, Redcar Creating a bridleway between proposed new housing estate and Saltburn Riding School Improve horse box parking locally Linking up existing bridleways to extend the local bridleway network including: o Mucky Lane and Errington Loop/Upleatham – via Tockett’s Mill? WEBSITE: www.saltburndistrictbridleways.co.uk EMAIL: [email protected] FIND US ON FACEBOOK AND FOLLOW US ON TWITTER @SADBG2000 o Yearby Woods to Wilton Woods or Kirkleatham to Lazenby Bank o Saltburn Riding School to Quarry Lane (SADBG already working with farmer on permissive route due to open September 2016 if all goes to plan!). -

Review of Polling Districts and Polling Places 2018 Consultation Report

Review of Polling Districts And Polling Places 2018 Consultation Report NOTICE OF POLLING DISTRICTS & POLLING STATION REVIEW Review of Polling Districts and Polling Places in accordance with the requirements of Section 18C(1) of the Representation of the People Act 1983 and Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England has now published its final recommendations for new electoral arrangements for Redcar & Cleveland Borough Council. The recommendations must now be approved by Parliament and a draft order, to bring in to force their recommendations, has been laid in Parliament. Subject to Parliamentary Scrutiny, the new electoral arrangements will come into force at the Local Elections in 2019. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England has recommended an increase in the number of wards within the Borough from 22 to 24. Each Ward is required to be sub-divided into polling districts; the number of polling districts will however decrease from 101 to 86. All polling districts have been re-categorised using with new reference letters which are more meaningful to the Ward and Parliamentary Constituency, for example BMTAM, where BMT reflects the ward (Belmont), A defines the sub district and M is the constituency the ward belongs to (Middlesbrough South and East Cleveland). A polling place is provided for electors living within each polling district. The changes to Wards mean that the Council was required to carry out a review of polling districts and polling places within the Borough, pursuant to Section 18C of the Representation of the People Act 1983. Redcar & Cleveland Borough Council is therefore conducting a review of the polling districts and polling places. -

Cleveland Naturalists' Field Club

CLEVELAND NATURALISTS’ FIELD CLUB RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS 1928 TO 1932 VOL.IV. Part 2 Edited by T.A. LOFTHOUSE F.R.I.B.A., F.E.S AND M. ODLING M.A., B.SC.,F.G.S. PRICE THREE SHILLINGS (FREE TO MEMBERS) MIDDLESBROUGH; H & F STOKELD 1932 85 CONTENTS Officers Elected at the 48th – 51st Annual Meeting - 85 - 86 48th-51st Annual Reports - 87 - 94 Excavations at Eston Camp 1929 – F Elgee - 95 Field Meetings and Lectures 1928-32 - 96 - 98 History of Natural History Societies in Middlesbrough - J.W.R Punch F.R.A.S. - 99 - 106 In Memoriam J.J. Burton O.B.E., J.P., F.R.A.S J.W.R.PUNCH, F.R.A.S. -107 - 110 In Memorium H. Frankland F.I.C. E.W.Jackson F.I.C., F.G.S -110 - 111 A Few Cleveland Place Names Major R.B.Turton - 112 - 118 The Cleveland Whin Dyke J J Burton O.B.E., J.P., F.G.S.,M.I.M.E - 119 -136 Notes on Wild Flowers Chas. Postgate & M Odling - 136 Report on Cleveland Lepidoptera T.A. Lofthouse, F.E.S. - 137 – 142 Coleoptera observed in Cleveland M.L. Thompson F.E.S. - 143 - 145 A Preliminary list of Cleveland Hemiptera M.L. Thompson F.E.S. - 146 – 156 Floods in the Esk Valley July 1930 and Sept 1931 – J.W.R.Punch F.R.A.S. - 156 – 166 Ornithological Notes in Yorkshire and South Durham – C E Milburn - 167 – 171 Meteorological Observations at Marton-in- Cleveland 1928-31 – M Odling M.A.,B.SC.,F.G.S - 172 – 176 Notes on the Alum Industry – H N Wilson F.I.C. -

NORTH :RIDING YORKSHIRE. [KELLY's Oc.Jst up by the Sea at Coatham About 1740, Aud Given £R,576: the Rev

156 KIRKLEATHAM. NORTH :RIDING YORKSHIRE. [KELLY'S oC.Jst up by the sea at Coatham about 1740, aud given £r,576: the Rev. Edwin Joseph Collins B.A. is chaplaiR. to the church by the lord of the manor : there is an Kirkleatham Hall, the property and seat of Gleadowe iron parish chest, fastened by a curiously-constructed Henry Turner N ewcomen esq. is a spacious and sub. luck: the church affords 300 sittings. The register st.antial mansion in the Tudor Gothic style, three storeys -dates from the year I559· The living is a vicarage, high and 132 feet in length, with an embattled parapet, net yearly value £174, including 13 acres of glebe, and is pleasantly situated and surrounded by woodland. with residence, in the gift of Gleadowe H. T. Newcomen The soil is clayey; subsoil, clay and stone. The chief esq. and held since 1910 by the Rev. Edwin Joseph crops are wheat, barley, beans and turnips. The area is Collins B.A. of St. Catharine's College, Cambridge. 3,533 acres of land, 5 of water and 481 of foreshore; rate. The impropriate tithe amounts to £soo. The hospital able valuP, £7,515; tJhe population in Ign was 632 iR here was founded and endowed in 1676 by Sir William the civil and 693 in the ecclesiastical parish. Turner kt. lord mayor of London, and a woollen draper Parish Clerk, William Burton ia St. Paul's churchyard, under letters patent under Wall Letter Box, Kh1.leatham, cleared 10 a.m. & s.:zo t:he Great Seal dated 2 March, 30 Charles II. -

Appendix 1– Schedule of Recommended Main Modifications

Appendix 1– Schedule of Recommended Main Modifications The modifications below are expressed either in the conventional form of strikethrough for deletions and underlining for additions of text, or by specifying the modification in words in italics. The page numbers and paragraph numbering below refer to the submission local plan, and do not take account of the deletion or addition of text. Policy/ Ref Page Main Modification Paragraph MM01 6 and Para. 1.9- Deleted – Refer to Inspector’s Report 7 1.14 MM02 14 Para. 1.47 Deleted – Refer to Inspector’s Report MM03 17 Para. 1.54 Deleted – Refer to Inspector’s Report – 1.56, 1.58, 1.59 and 1.61 MM04 19 Paras. 1.64 1.64 The Council’s Regeneration Masterplan sets out an ambitious vision to create 14,000 new and 1.65 jobs, support and help create over 800 business and secure £1bn of private and £265m of public sector investment in the borough over the next fifteen years. 1.65 The Council has also prepared an Economic Growth Strategy which seeks to reinforce the delivery of the Council’s Regeneration Masterplan. The Strategy seeks to accelerate diversification and growth of local economic activity through a clear focus on economic development properties and outcomes. This economic growth focus complements and reinforces the broader set of outcomes encapsulated in the Regeneration Masterplan. It provides a framework for prioritising future public growth, and the alignment of expertise and capacity to maximise benefits for Redcar & Cleveland and the Tees Valley. Policy/ Ref Page Main Modification Paragraph MM05 38 Policy SD2 Development will be directed to the most sustainable locations in the borough. -

Redcar & Cleveland Ironstone Heritage Trail

Redcar & Cleveland Ironstone Heritage Trail Car and Walk Trail this is Redcar & Cleveland Redcar & Cleveland Ironstone Heritage Trail The History of Mining Ironstone Villages Ironstone mining began in Redcar & A number of small villages grew up in Cleveland in the 1840s, with the East Cleveland centred around the Redcar & Cleveland collection of ironstone from the ironstone mines and the differing Ironstone Heritage Trail foreshore at Skinningrove. A drift mine facilities available at these villages. celebrates the iron and steel was opened in the village in 1848. The Those that were established by ironstone industry on Teesside grew Quaker families did not permit public history of the Borough. Linking rapidly following the discovery of the houses to be built. At New Marske, Eston and Skinningrove, the Main Seam at Eston on 8th June 1850 the owners of Upleatham Mine, the by John Vaughan and John Marley. In two areas that were both Pease family, built a reading room for September a railway was under the advancement of the mining integral to the start of the construction to take the stone to both industry, the trail follows public the Whitby-Redcar Railway and the community. In many villages small schools and chapels were footpaths passing industrial River Tees for distribution by boat. The first stone was transported along the established, for example at Margrove sites. One aspect of the trail is branch line from Eston before the end Park. At Charltons, named after the that it recognises the of 1850. Many other mines were to first mine owner, a miners’ institute, commitment of many of the open in the following twenty years as reading room and miners’ baths were the industry grew across the Borough. -

Redcar and Cleveland Authority's Monitoring Report 2017-2018

Redcar & Cleveland Authority’s Monitoring Report 2017-2018 this is Redcar & Cleveland 1.0 Introduction 1 - What is the Authority’s Monitoring Report (AMR)? 1 - Why monitor? 1 - How is the report structured? 2 - Further information 2 2.0 A place called Redcar and Cleveland 3 3.0 Monitoring plan making 5 - Have there been any significant changes to national planning policy? 5 - What progress has been made on the Local Development Plan? 7 4.0 Economic development 13 5.0 Housing 27 Contents 6.0 Transport and community infrastructure 39 7.0 Environmental quality 43 this is Redcar & Cleveland 1.1 What is the Authority’s Monitoring Report? The Authority’s Monitoring Report (AMR) is part of the Redcar & Cleveland Local Development Plan (LDP). Its key purpose is to assess the progress made in preparing the LDP, the effectiveness of LDP policies and to make any recommendations on where policy changes should be made. This AMR covers the period 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018, and also includes anything significant which has happened since this monitoring period. 1.2 Why do we need to monitor? Monitoring is a vital process of plan and policy making. It reports on what is happening now and what may happen in the future. These trends are assessed against existing policies and targets to determine whether or not current policies are performing as expected, ensuring that the LDP continues to contribute to the attractiveness and functionality of Redcar and Cleveland as a place to live, work, invest and visit. Up until now, the AMR has monitored trends to assess the performance of the policies within the Local Development Framework (LDF), which is made up of the Core Strategy Development Plan Document (DPD) and Development Policies DPD and the Saved Policies of the 1999 Local Plan. -

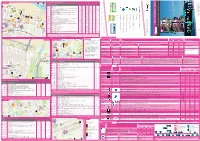

B Us Train M Ap G Uide

R d 0 100 metres Redcar Town Centre Bus Stands e r n Redcar m d w G d B d e o i i e a u Stand(s) i w r t r 0 100 yards h c e s Service l t e w . h c t t Key destinations u c Redcar Wilton High Street Bus Railway Park e t i y . number e m t N Contains Ordnance Survey data e b t o e u © Crown Copyright 2016 Clock Street East Station # Station Avenue t e e v o l s g G y s Regent x l N t e Digital Cartography by Pindar Creative o 3 w i t y o m c ◆ Marske, Saltburn, Skelton, Lingdale A–L Q ––– f o e m Cinema B www.pindarcreative.co.uk a r u e o ©P1ndar n t o e l u r d v u s m T s e r Redcar Redcar Clock C–M R ––– m f r s a r o y c e P C e r n t o Beacon m s e r r y e o . b 22 Coatham, Dormanstown, Grangetown, Eston, Low Grange Farm, Middlesbrough F* J M R* 1# –– a m o d e o t i v a u u l n t e b e o r c r s t l s e b Ings Farm, The Ings , Marske , New Marske –HL Q ––– i . ◆ ◆ ◆ i T t l . n d c u Redcar and Cleveland o e i . u a p p r e a N n e Real Opportunity Centre n o 63 Lakes Estate, Eston, Normanby, Ormesby, The James Cook University Hospital, D G* H# K* –2– – e e d j n E including ShopMobility a r w p Linthorpe, Middlesbrough L# Q# n S W c r s i t ’ Redcar Sands n d o o r e S t e St t t d e m n t la e 64 Lakes Estate, Dormanstown, Grangetown, Eston, South Bank, Middlesbrough F* J M P* 1# 2– c Clev s S a e n d t M . -

Popular Political Oratory and Itinerant Lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the Age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa M

Popular political oratory and itinerant lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa Martin This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of York Department of History January 2010 ABSTRACT Itinerant lecturers declaiming upon free trade, Chartism, temperance, or anti- slavery could be heard in market places and halls across the country during the years 1837- 60. The power of the spoken word was such that all major pressure groups employed lecturers and sent them on extensive tours. Print historians tend to overplay the importance of newspapers and tracts in disseminating political ideas and forming public opinion. This thesis demonstrates the importance of older, traditional forms of communication. Inert printed pages were no match for charismatic oratory. Combining personal magnetism, drama and immediacy, the itinerant lecturer was the most effective medium through which to reach those with limited access to books, newspapers or national political culture. Orators crucially united their dispersed audiences in national struggles for reform, fomenting discussion and coalescing political opinion, while railways, the telegraph and expanding press reportage allowed speakers and their arguments to circulate rapidly. Understanding of political oratory and public meetings has been skewed by over- emphasis upon the hustings and high-profile politicians. This has generated two misconceptions: that political meetings were generally rowdy and that a golden age of political oratory was secured only through Gladstone’s legendary stumping tours. However, this thesis argues that, far from being disorderly, public meetings were carefully regulated and controlled offering disenfranchised males a genuine democratic space for political discussion. -

Redcar and Cleveland Regeneration Masterplan

Redcar and Cleveland Regeneration Masterplan Economic Futures: A Regeneration Strategy for Redcar & Cleveland April 2010 this is Redcar & Cleveland 1 C 2 Contents Foreword Page 4 C Executive Summary Page 6 Part One: Drivers of Change Page 16 1 The Regeneration Masterplan 2 The Context for Change 3 Economic Drivers 4 Redcar & Cleveland 2025 Part Two: Strategies for Change Page 34 1 Economic 2 Sustainable Communities 3 Connectivity 4 Environment and Infrastructure 5 Spatial Masterplan Part Three: Delivering change Page 76 1 Delivery Strategy 2 Flexibility of Delivery 3 Foreword F 4 Foreword: Councillor Mark Hannon, Portfolio Holder for Economic Development. The Regeneration Masterplan lays out a long-term 15 year plan The global recession of 2008-11 has highlighted the Redcar & for the social, economic & physical development of the Borough. Cleveland economy’s reliance on external markets for products It includes proposed changes in size, form, character, image of steel and petro-chemical processes. The vulnerability of and environment - all the things you told us were important as local operations to global decision making, the depth of supply part of the Love it Hate it consultation. chain dependence, the relatively undeveloped service sector that in other industrial economies has provided a balance of We recognise that to maintain the status quo is not acceptable, employment and the ongoing difficulty in making real in-roads improvements must be made to provide decent homes and into deprivation – these issues have been starkly presented Fgood transport links, creating jobs and improving social and though the recent recession. environmental conditions. By connecting people, places and movement through the Masterplan we aim to foster a sense of Responding to these challenges on an ad hoc and individual community wholeness and well-being.