Report of the 7 July Review Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

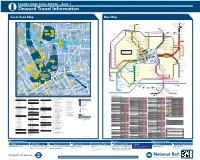

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

Chipping Barnet Constituency Insight and Evidence Review

Chipping Barnet Constituency Insight and Evidence Review 1 Contents 1 Introduction....................................................................................................................................3 2 Overview of Findings ......................................................................................................................3 2.1 Challenges of an ageing & isolated population ......................................................................3 2.2 Pockets of relative deprivation...............................................................................................4 2.3 Obesity and Participation in Sport..........................................................................................4 3 Recommended Areas of Focus .......................................................................................................5 4 Summary of Key Facts.....................................................................................................................6 4.1 Population ..............................................................................................................................6 4.2 Employment ...........................................................................................................................6 4.3 Deprivation .............................................................................................................................6 4.4 Health .....................................................................................................................................7 -

Vinyl Theory

Vinyl Theory Jeffrey R. Di Leo Copyright © 2020 by Jefrey R. Di Leo Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to publish rich media digital books simultaneously available in print, to be a peer-reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. The complete manuscript of this work was subjected to a partly closed (“single blind”) review process. For more information, please see our Peer Review Commitments and Guidelines at https://www.leverpress.org/peerreview DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11676127 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-015-4 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-016-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019954611 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Without music, life would be an error. —Friedrich Nietzsche The preservation of music in records reminds one of canned food. —Theodor W. Adorno Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments vii Preface 1 1. Late Capitalism on Vinyl 11 2. The Curve of the Needle 37 3. -

How to Find Us Garfield House, 86-88 Edgware Road, London W2 2EA

How to find us etc.venues Marble Arch is located on Edgware Road in the heart of the West End. By underground Central line to Marble Arch Station – when you exit the station, turn right on to Oxford Street and then right again on to Edgware Road walking past the Odeon Cinema. etc.venues Garfield House, 86-88 Edgware Road, London W2 2EA Marble Arch is in Garfield House, on the right hand side next to the Tescos. Tel: 020 7793 4200 Fax: 020 7793 4201 By train Email: [email protected] Paddington station is approximately 20 minutes walk. Use the Praed Street exit and turn left on Sat nav: 51.51542, -0.163319 to Praed Street and continue until you walk on to Edgware Road. Turn right onto Edgware Road and continue towards Marble Arch. GLO etc.venues Marble Arch is at the other end of A5 T S Y B Edgware Road on the left. Alternatively bus W B U R O CEST R R O routes 36 or 436 go from outside Paddington A W H N Garfield House on Praed Street and on to Edgware Road and S E T E ST R P 86-88 Edgware Road take approximately 10 minutes to Marble Arch. O RG GE London W2 2EA L G ACE EDG REAT By bus S TESCOTESCO EYMOU WAR etc.venues Marble Arch sits on many bus METROMETRO CU Y ST A41 KELE routes including 7, 10, 73, 98, 137, 390, 6, 23, E M E R R B BERL P E R 94, 159, 30, 94, 113, 159, 274, 2, 16, 36, 74, U P P RD L ACE 82, 148, 414, 436 AN 4 D A520 PL G H T ST Parking R A ST CONNAU M OU CE There is a NCP car park situated within close S EY proximity to Marble Arch - visit www.ncp.co.uk A5 ODEANODEAN MARBLEMARBLE MARBLEMARBLE ARCHARCH for more details. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

Barnet Seniors' Association

Barnet Seniors’ Insider Produced by: News for senior citizens in Barnet * Keeping well * Staying safe * Being active * Making friends IF YOU DON’T NEED THIS NEWSLETTER, PLEASE PASS IT ON TO SOMEONE WHO MIGHT Issue 13 ● July / Aug 2017 All together now Singing has health benefits – but it’s also fun There has been so much publicity The Big Choir is a community fundraising recently about the health benefits of choir that was formed in 2016 to raise choral singing that it has almost money for Cancer Research UK. They are IN THIS ISSUE become the vocal equivalent of jogging a modern choir singing many different Ransackers Project – we should all be doing it because it’s styles from a capella to pop, from Beatles Fremantle Trust good for us. to Bob Marley. Their members range in Electrical Safety age from 20’s to 80’s. They have one Electrical Fires There’s certainly evidence that singing daytime session and one evening. Full Rogue Traders improves lung capacity in people details of sessions can be found on Pension Credit suffering from pulmonary disease, and www.thebigchoir.org A free taster session Out and About it has been shown to help people will be offered to anyone who would like to suffering from depression and other think about joining. Mainly for people mental health problems. Contact Sharon Czapnik Down aged 55 or over But the stress on the fact that ‘singing is Mobile: 07971 957188 Welcome to this issue of Barnet Seniors’ Assembly newsletter for those people good for you’ emphasises its’ health Email: [email protected] mainly over the age of 55 in the London benefits, yet rather ignores the fact that Edgware Community Chorus is of mixed Borough of Barnet. -

Whitechapel Mile End Bow Road Bow Church Stepney Green Aldgate

Barclays Cycle Superhighway Route 2 Upgrade This map shows some of the main changes proposed along the route. For detailed proposals, visit tfl.gov.uk/cs2upgrade No right turn from Whitechapel Road Bus lane hours of operation into Stepney Green changed to Mon-Sat, 4pm-7pm No right turn from between Vallance Road and Whitechapel High Street Cambridge Heath Road into Leman Street N ST. BOTOLPH Whitechapel Stepney Green STREET VALLANCE ROAD VALLANCE GLOBE ROAD GLOBE OSBORN STREET Aldgate STREETCOMMERCIAL CAMBRIDGE HEATH ROAD WHITECHAPEL ROAD City of London Aldgate scheme COMMERCIAL ROAD The Royal London Aldgate Hospital East FIELDGATE STREET NEW ROAD LEMAN STREET LEMAN SIDNEY STREET STEPNEY GREEN STEPNEY MANSELL STREET MANSELL Continued below Continued No right turn from Mile End Road into Burdett Road NORTHERN APPROACH NORTHERN RIVER LEA RIVER Queen Mary University of London FAIRFIELD ROAD FAIRFIELD GROVE ROAD GROVE COBORN ROAD COBORN Continued above CS2 continues MILE END ROAD BOW ROAD HIGH STREET to Stratford Mile End Bow Road Bow Church BROMLEY HIGH STREET No right turn from TUNNEL CAMPBELL ROAD CAMPBELL BURDETTROAD HARFORD STREET HARFORD REGENT’S CANAL Burdett Road into Bow Road MORNINGTON GROVE BLACKWALL Kerb-separated cycle track New bus stop Major upgrade to junction Changes to be proposed under Vision for Bow scheme Wand-separated cycle lane Bus stop removed Other road upgrade scheme . -

Mile End Old Town, 1740-1780: a Social History of an Early Modern London Suburb

REVIEW ESSAY How Derek Morris and Kenneth Cozens are rewriting the maritime history of East London North of the Thames: a review Derek Morris, Mile End Old Town, 1740-1780: A Social History of an Early Modern London Suburb. 1st ed, 2002; 2nd ed., The East London History Society, 2007; a new edition in process to be extended back in time to cover from 1660; Derek Morris and Ken Cozens, Wapping, 1600-1800: A Social History of an Early Modern London Maritime Suburb. The East London History Society, 2009; Derek Morris, Whitechapel 1600-1800: A Social History of an Early Modern London Inner Suburb. The East London History Society, 2011; £12.60 and £3:50 p&p (overseas $18.50), http://wwww.eastlondonhistory .org.uk In three books published to date, two London-based researchers, Derek Morris and Kenneth Cozens, have set about the task of challenging many deeply-held stereotypes of London’s eastern parishes in the eighteenth century. With meticulous attention to detail, and with sure control of a wide range of archives, they have produced three highly-recommended works. The books Mile End and Wapping are in very short supply, if not by the time of this review, only available on the second-hand market. In Whitechapel, with the completion of the first phase of their research, they have ignored the restrictions imposed by parish boundaries: they have begun to draw conclusions about the nature of society in these areas in the eighteenth century. This is welcome for a number of reasons. But chief among these is that for too long historians have relied on a series of stereotypes with the emphasis on poverty, crime and “dirty industries,” to portray these eastern parishes, when in fact the emphasis should be on the important role played by local entrepreneurs in London’s growing economy and worldwide trading networks. -

The Who, the Mods and the Quadrophenia Connection the Who

Vintage Rock DVD Review: The Who, The Mods And The Quadrophenia... http://www.vintagerock.com/classiceye/who_mods_quadrophenia_dvd.aspx Home News Digital Lounge Giveaways YouTube Twitter MySpace Blog Forum Contact Us The Who, The Mods And The Quadrophenia Connection The Who Critical analysis of rock and roll can be a sticky wicket to be sure. When critics pro and con, musicologists and teachers attempt to dissect music that makes you tap your foot or sends chills up your spine, they often leave one cold with conjecture and theories. I'm not damning critics; the sheer act of addressing heavier themes in the music I love justifies what I have said for so long about how important the music is. Still, a DVD like The Who, The Mods And The Quadrophenia Connection scares me in its possible potential of too much talk about a great double disc album that…makes me tap my foot and sends chills down my spine. I needn't have worried. With commentary from the likes of Richard Barnes, The Who's 'Mr. Fixit' and Pete Townsend bud, mod 'experts Paolo Hewitt and Terry Rawlins, members of the Mod revival bands the Chords and the Purple Hearts, and Who biographer Alan Clayson, The Who, The Mods And The Quadrophenia Connection is a delightful history lesson from guys who obviously love the music of the Who first and foremost. Snippets from the 1979 Quadrophenia film are mixed in with rarely seen performances of the Kinks, the Who and Gerry and the Pacemakers, plus news footage of the day, and scenes from the mod/rocker movement shown on 60s British TV. -

London Buses - Route Description

Printed On: 07 May 2015 09:17:25 LONDON BUSES - ROUTE DESCRIPTION ROUTE 605: Edgware Bus Station - Totteridge & Whetstone Station Date of Structural Change: 6 September 2013. Date of Service Change: 20 September 2014. Reason for Issue: Additional return journey introduced between Burnt Oak Station and Totteridge & Whetstone Station. STREETS TRAVERSED Towards Totteridge & Whetstone Station: Edgware Bus Station, Station Road, Edgware High Street, Burnt Oak Broadway, Watling Avenue, Woodcroft Avenue, Bunn's Lane, The Broadway, Mill Hill Circus, Watford Way (Barnet By-Pass), Northway Circus, Barnet Way (Barnet By-Pass), Marsh Lane, Highwood Hill, Totteridge Common, Totteridge Village, Totteridge Lane. Towards Edgware Bus Station: Totteridge Lane, Totteridge Village, Totteridge Common, Highwood Hill, Holcombe Hill, The Ridgeway, Hammers Lane, Daws Lane, Albert Road, Victoria Road, Lawrence Street, Mill Hill Circus, The Broadway, Mill Hill Broadway Bus Station, The Broadway, Bunn's Lane, Woodcroft Avenue, Watling Avenue, Burnt Oak Broadway, Edgware High Street, Station Road, Edgware Bus Station. School Journey from Mill Hill, Marsh Lane: One afternoon journey operate from Marsh Lane to Highwood Hill. AUTHORISED STANDS, CURTAILMENT POINTS, & BLIND DESCRIPTIONS Please note that only stands, curtailment points, & blind descriptions as detailed in this contractual document may be used. EDGWARE STATION, BUS STATION Buses proceed out of service from Edgware Bus Station. Buses depart from out of service to Edgware Bus Station. Set down in Edgware Bus Station, at Stop G (BP090 - Edgware Station <>, Last Stop on LOR: BP090 - Edgware Station <>) and pick up in Edgware Bus Station, at Stop D (R0790 - Edgware Bus Station, First Stop on LOR: R0790 - Edgware Bus Station). -

Mercedes-Benz and Smart Colindale, Brent

MERCEDES-BENZ AND SMART COLINDALE, BRENT Feasibility Study November 2019 MERCEDES-BENZ AND SMART COLINDALE, BRENT Site and context 1 LOCATION PLAN N EDGWARE ROAD CARLISLE ROAD CAPITOL WAY STAG LANE Existing site location plan - Mercedes-Benz and Smart Colindale, 403 Edgware Road, London Borough of Brent (LBB) Mercedes-Benz and Smart site boundary: 1.47ha / 3.64ac LBB proposed site allocation area (BNSA1: Capitol Way Valley) 2 MERCEDES-BENZ AND SMART COLINDALE, BRENT Title Site and context Title pageheader Aerial Photograph Fig ?.?: Caption title ?????? MERCEDES-BENZ AND SMART COLINDALE, BRENT Site and context THE EXISTING SITE 2 TNQ 19-storey tower TNQ behind the site Edgware Road 1 Mercedes-Benz frontage onto Edgware Road basement access access from Edgware Raoad Aerial photograph from the north east* Edgware Road 1 2 3 rear of Mercedes-Benz and Smart site 2 Carlisle Road N 3 Plan showing location of street views Street views of the existing site and context* *images from Google Earth 4 MERCEDES-BENZ AND SMART COLINDALE, BRENT Site and context RECENT MIXED USE DEVELOPMENTS 3 Burnt Oak Broadway - complete (app. no. 05-0380) Mixed use development - retail floorspace + 73 residential units (266dph) 5-6 storeys Residential parking ratio: 0.9 spaces / unit 3 Burnt Oak Broadway London Borough London Borough of Brent of Barnet EDGWARE ROAD Green Point - complete (Barnet - app. no. H-03389-13) Green Point Mixed use development - A1 retail / B1 floorspace + 86 residential units (218 dph) 8 storeys CARLISLE ROAD Residential parking ratio: 1.4 spaces / unit The Northern Quarter (TNQ) - complete/tower under construction (app. -

Singles 1970 to 1983

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS PHILIPS–PHONOGRAM 7”, EP’s and 12” singles 1970 to 1983 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 PHILIPS-PHONOGRAM, 1970-83 2001 POLYDOR, ROCKY ROAD, JET 2001 007 SYMPATHY / MOONSHINE MARY STEVE ROWLAND & FAMILY DOGG 5.70 2001 072 SPILL THE WINE / MAGIC MOUNTAIN ERIC BURDON & WAR 8.70 2001 073 BACK HOME / THIS IS THE TIME OF THE YEAR GOLDEN EARRING 10.70 2001 096 AFTER MIDNIGHT / EASY NOW ERIC CLAPTON 10.70 2001 112 CAROLINA IN MY MIND / IF I LIVE CRYSTAL MANSION 11.70 2001 120 MAMA / A MOTHER’S TEARS HEINTJE 3.71 2001 122 HEAVY MAKES YOU HAPPY / GIVE ‘EM A HAND BOBBY BLOOM 1.71 2001 127 I DIG EVERYTHING ABOUT YOU / LOVE HAS GOT A HOLD ON ME THE MOB 1.71 2001 134 HOUSE OF THE KING / BLACK BEAUTY FOCUS 3.71 2001 135 HOLY, HOLY LIFE / JESSICA GOLDEN EARING 4.71 2001 140 MAKE ME HAPPY / THIS THING I’VE GOTTEN INTO BOBBY BLOOM 4.71 2001 163 SOUL POWER (PT.1) / (PTS.2 & 3) JAMES BROWN 4.71 2001 164 MIXED UP GUY / LOVED YOU DARLIN’ FROM THE VERY START JOEY SCARBURY 3.71 2001 172 LAYLA / I AM YOURS DEREK AND THE DOMINOS 7.72 2001 203 HOT PANTS (PT.1) / (PT.2) JAMES BROWN 10.71 2001 206 MONEY / GIVE IT TO ME THE MOB 7.71 2001 215 BLOSSOM LADY / IS THIS A DREAM SHOCKING BLUE 10.71 2001 223 MAKE IT FUNKY (PART 1) / (PART 2) JAMES BROWN 11.71 2001 233 I’VE GOT YOU ON MY MIND / GIVE ME YOUR LOVE CAROLYN DAYE LTD.