Newburn Ford 1640

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tyne River House Thefor Watermark, Gateshead, SALE NE11 9SZ

INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY Tyne River House TheFOR Watermark, Gateshead, SALE NE11 9SZ High Yielding Single Let Office Investment INVESTMENT SUMMARY • Located on The Watermark Business Park, Gateshead’s • Freehold premier out of town office location. • Tenant has committed circa £2.35 million to the building through an • Tyne River House comprises a modern 2,786 sq m (29,999 sq ft) extensive refurbishment and fit out, comprising a new VRF heating and purpose built stand-alone office building with extensive parking cooling system, lighting, suspended ceilings and speedgate turnstiles. provision (1:269 sq ft). • Annual rent of £423,080 (£14.10 psf). • Excellent transport connections sitting adjacent to the bus and rail • We have been instructed to seek offers in excess of £3,610,000 for our interchange and a two minute drive to A1 junction 71, providing clients’ freehold interest. A purchase at this level reflects an attractive rapid access to the wider region. NIY of 11.00% and a low capital value of £120 psf assuming purchasers • Fully let to Teleperformance Limited on a new 10 year FRI lease costs of 6.509%. from 15 November 2016 with approximately 9.76 years remaining (4.76 to break). 2 A1 ALNWICK ASHINGTON MORPETH A1(M) LOCATION A696 A68 Newcastle Airport A19 TYNEMOUTH Port of Tyne Tyne River House is located on the NEWCASTLE A69 SOUTH A69 UPON TYNE Watermark Business Park which lies within SHIELDS the Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead. GATESHEAD Gateshead has a population of 200,500 Tyne River SUNDERLAND people extending to 1,075,000 people in House Intu the wider Tyneside conurbation. -

The Glass Houses of Alfred Alexander Bill Lockhart

The Glass Houses of Alfred Alexander Bill Lockhart Alfred Alexander and his two sons, Alfred (junior) and George, were involved in a series of English bottle factories during the last half of the 19th century and the early 20th century. The firm made a large variety of bottles, including “pale” soda bottles at the Hunslet, Leeds, factory. Some of their bottles were used by U.S. and Canadian bottlers. Histories Blaydon Glass Bottle Co, Blaydon, Durham, England (1854-1860) Yorkshire Bottle Co., London, England (1854-1860) In 1854, Anthony Thatcher established a bottle plant at Blaydon-on-Tyne, Durham, England. The factory was called the Blaydon Bottle Works, although it is unclear whether that was an official name. By at least the following year, Alfred Alexander was the agent for the Yorkshire Bottle Co., with a warehouse at Victoria Wharf on Earl St. and a sales office on Upper Thames St., both in London (McFarlane 2009; North East Bottle Collectors 2011). At some point, possibly from the beginning, Alfred Alexander, Anthony Thatcher, James Battle Austin, and Henry Poole formed a partnership – the Blaydon Glass Bottle Co. – to operate the Blaydon plant. We have discovered virtually nothing about the operation of the factory during this period, although the partnership was formed as “Bottle Manufacturers and Bottle Merchants.” Thatcher retired, so the partnership dissolved on July 2, 1860 (McFarlane 2009). Alexander, Austin & Poole, Blaydon (1860-1861) With the retirement of Thatcher, the remaining three – Alexander, Austin & Poole – operated the Blaydon plant under this name for a brief period. The Yorkshire Bottle Co. -

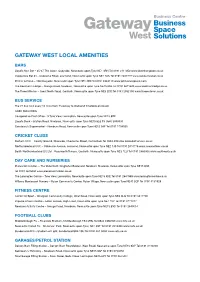

Gateway West Local Amenities

GATEWAY WEST LOCAL AMENITIES BARS Lloyd’s No1 Bar – 35-37 The Close, Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3RN Tel 0191 2111050 www.jdwetherspoon.co.uk Osbournes Bar 61 - Osbourne Road, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 2AN Tel 0191 2407778 www.osbournesbar.co.uk Pitcher & Piano – 108 Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3DX Tel 0191 2324110 www.pitcherandpiano.com The Keelman’s Lodge – Grange Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NL Tel 0191 2671689 www.keelmanslodge.co.uk The Three Mile Inn – Great North Road, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 2DS Tel 0191 2552100 www.threemileinn.co.uk BUS SERVICE The 22 bus runs every 10 mins from Throckley to Wallsend timetable enclosed CASH MACHINES Co-operative Post Office - 9 Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Lloyd’s Bank – Station Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8LS Tel 0845 3000000 Sainsbury’s Supermarket - Newburn Road, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 9AF Tel 0191 2754050 CRICKET CLUBS Durham CCC – County Ground, Riverside, Chester-le-Street, Co Durham Tel 0844 4994466 www.durhamccc.co.uk Northumberland CCC – Osbourne Avenue, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 1JS Tel 0191 2810775 www.newcastlecc.co.uk South Northumberland CC Ltd – Roseworth Terrace, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 1LU Tel 0191 2460006 www.southnort.co.uk DAY CARE AND NURSERIES Places for Children – The Waterfront, Kingfisher Boulevard, Newburn Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NZ Tel 0191 2645030 www.placesforchildren.co.uk The Lemington Centre – Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Tel 0191 2641959 -

Tyne Estuary Partnership Report FINAL3

Tyne Estuary Partnership Feasibility Study Date GWK, Hull and EA logos CONTENTS CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 2 PART 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 6 Structure of the Report ...................................................................................................... 6 Background ....................................................................................................................... 7 Vision .............................................................................................................................. 11 Aims and Objectives ........................................................................................................ 11 The Partnership ............................................................................................................... 13 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 14 PART 2: STRATEGIC CONTEXT ....................................................................................... 18 Understanding the River .................................................................................................. 18 Landscape Character ...................................................................................................... 19 Landscape History .......................................................................................................... -

Throckley Leazes Tenants and Residents Group

Throckley Leazes Tenants and Residents Group Established January 1998 Chairman Jennie Stokell Vice Chairman Secretary Carol Eddy Treasurer Sheila Grey Monday 22 August 2016 David Owen, Review Officer, (Newcastle upon Tyne) Local Government Boundary Commission for England, 14th Floor, Millbank Tower, Millbank, London, SW1P 4QP. Dear Sir or Madam, Ref : City of Newcastle upon Tyne - Draft Recommendations on New Electoral Arrangements - Callerton Throckley I have been asked by our Ward Counsellors to thank you for putting Walbottle back into this electoral ward. My Group are still not happy about this new ward created by apparently adding odd bits of the outer City to Newburn, Throckley, etc, to create a “patchwork” ward with little cohesion along its length once away from the riverside settlements. Our objections are as follows 1. Consultation. My Group are disappointed that the City Council have again failed to publise this consultation about the proposed changes to the ward boundaries and the implications to the people living in the areas. We have found when raising the issue at our meetings and in private conversations, that there is more interest than we would have expected once the whole project relating to the proposed changes around Throckley and Newburn are explained. This interest is across the age ranges of residents, not simply among the elderly who have memories of the Newburn Urban District Council and its governance of the area prior to Newburn, etc. inclusion in the City of Newcastle upon Tyne. Local people are possessive of the long term history of their area and the events which make up their social and cultural heritage. -

Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust

Whitley Bay From Morpeth A193 Gateshead Health Alnwick A1 A189 A192 NHS Trust 0 2miles A1056 0 2 4km A19 Bensham Hospital Newcastle Fontwell Drive Airport Bensham B1318 A191 Tynemouth Gateshead NE8 4YL Kingston Tel: 0191 482 0000 Park Gosforth A193 A68 A1068 Otterburn A697 A189 A191 A1 Ashington A696 Morpeth South Blyth A191 Shields A696 A1 Wallsend A189 A1058 A187 A193 A183 A68 A1 North A19 A1058 Shields A167 A187 Haltwhistle A69 Tyne A69 Newcastle r Tyn Tunnel A1018 Brampton A69 A193 Rive e Hexham Gateshead Sunderland Newcastle A686 A692 J65 upon Tyne A185 A194 A689 Consett A693 A187 Alston A6085 A691 A1M A186 A68 A19 Tyne Hebburn Durham Central A167 Bridge A1300 A695 A186 From the A1 A695 A189 A185 Exit the A1 at the junction with the A692/B1426. Join the B1426 Lobley Hill Road. Gateshead Blaydon MetroCentre At the roundabout take the second exit (still Lobley A184 A194 A19 Hill Road). A1 A184 Whickham B1426 Continue under the railway bridge and at the traffic See Inset lights turn right onto Victoria Road. A184 A184 From Continue to the end and at the T-junction turn left A167 B1296 onto Armstrong Street. Sunderland d a Take the second right (just before the railway bridge) o R onto Fontwell Drive. m Inset a h s The Hospitals main entrance is situated at the end n e B Angel of of Fontwell Drive. the North S By Rail a A194M lt A1231 w Take the Intercity service to Newcastle upon Tyne. e B1426 ll A frequent service on the Metro light railway runs ad Ro Dunsmuir Grove ll V to Gateshead Interchange. -

Bridges Over the Tyne Session Plan

Bridges over the Tyne Session Plan There are seven bridges over the Tyne between central Newcastle and Gateshead but there have been a number of bridges in the past that do not exist anymore. However the oldest current bridge, still standing and crossing the Tyne is actually at Corbridge, built in 1674. Pon Aelius is the earliest known bridge. It dates from the Roman times and was built in the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian at the same time as Hadrian’s Wall around AD122. It was located where the Swing Bridge is now and would have been made of wood possibly with stone piers. It last- ed until the Roman withdrawal from Britain in the 5th century. Two altars can be seen in the Great North Museum to Neptune and Oceanus. They are thought to have been placed next to the bridge at the point where the river under the protection of Neptune met the tidal waters of the sea under the protection of Oceanus. The next known bridge was the Medieval Bridge. Built in the late 12th century, it was a stone arched bridge with huge piers. The bridge had shops, houses, a chapel and a prison on it. It had towers with gates a drawbridge and portcullis reflecting its military importance. The bridge collapsed during the great flood of 1771, after three days of heavy rain, with a loss of six lives. You can still see the remains of the bridge in the stone archways on both the Newcastle and Gateshead sides of the river where The Swing Bridge is today. -

S844 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S844 bus time schedule & line map S844 Allerdene - Blaydon View In Website Mode The S844 bus line (Allerdene - Blaydon) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Allerdene: 3:40 PM (2) Blaydon: 7:30 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S844 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S844 bus arriving. Direction: Allerdene S844 bus Time Schedule 32 stops Allerdene Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational St Thomas More Catholic School, Blaydon 14 Croftdale Road, Blaydon Tuesday Not Operational Blaydon Bank-Croftdale Road, Blaydon Wednesday Not Operational 42 Bowland Crescent, Blaydon Thursday 3:40 PM Blaydon Bank-Lawrence Court, Blaydon Friday 3:40 PM 8 Lawrence Court, Blaydon Saturday Not Operational Chainbridge Road-Whiteley Road, Blaydon Riverside Way-Clasper Way, Metrocentre Riverside Way, Metrocentre S844 bus Info Direction: Allerdene Handy Drive-Bus Depot, Metrocentre Stops: 32 Trip Duration: 35 min St Omers Road, Dunston Line Summary: St Thomas More Catholic School, Railway Street, Gateshead Blaydon, Blaydon Bank-Croftdale Road, Blaydon, Blaydon Bank-Lawrence Court, Blaydon, Chainbridge Colliery Road, Dunston Road-Whiteley Road, Blaydon, Riverside Way-Clasper Way, Metrocentre, Riverside Way, Metrocentre, Clockmill Road, Teams Handy Drive-Bus Depot, Metrocentre, St Omers Road, Dunston, Colliery Road, Dunston, Clockmill Road, Derwentwater Road-Teams Bridge, Teams Teams, Derwentwater Road-Teams Bridge, Teams, Derwentwater Road-Pitz, Teams, Johnson Street, -

Gateshead & Newcastle Upon Tyne Strategic

Gateshead & Newcastle upon Tyne Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2017 Report of Findings August 2017 Opinion Research Services | The Strand • Swansea • SA1 1AF | 01792 535300 | www.ors.org.uk | [email protected] Opinion Research Services | Gateshead & Newcastle upon Tyne Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2017 August 2017 Opinion Research Services | The Strand, Swansea SA1 1AF Jonathan Lee | Nigel Moore | Karen Lee | Trevor Baker | Scott Lawrence enquiries: 01792 535300 · [email protected] · www.ors.org.uk © Copyright August 2017 2 Opinion Research Services | Gateshead & Newcastle upon Tyne Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2017 August 2017 Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................ 7 Summary of Key Findings and Conclusions 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Calculating Objectively Assessed Needs ..................................................................................................... 8 Household Projections ................................................................................................................................ 9 Affordable Housing Need .......................................................................................................................... 11 Need for Older Person Housing ................................................................................................................ -

Sunderland - Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Sundays

Sunderland - Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Sundays Middlesbrough d - - 0832 - - 0931 - - 1031 - Hartlepool d - - 0903 - - 1001 - - 1101 - Horden d - - 0914 - - 1012 - - 1112 - Sunderland d - - 0932 - - 1030 - - 1130 - Newcastle a - - 0951 - - 1050 - - 1150 - d 0845 0930 0955 1016 1035 1055 1115 1133 1155 1215 Dunston - 0935 - 1021 - - 1121 - - 1220 MetroCentre a 0852 0939 1002 1025 1043 1102 1124 1141 1202 1224 d 0853 - 1003 - - 1103 - - 1203 - Blaydon 0857 - 1007 - - - - - 1207 - Wylam 0903 - 1013 - - 1111 - - 1213 - Prudhoe 0908 - 1017 - - 1115 - - 1218 - Stocksfield 0912 - 1022 - - 1120 - - 1222 - Riding Mill 0917 - 1026 - - 1124 - - 1227 - Corbridge 0921 - 1030 - - 1128 - - 1231 - Hexham a 0927 - 1036 - - 1134 - - 1237 - d 0927 - 1037 - - 1135 - - 1237 - Haydon Bridge 0937 - 1046 - - 1144 - - - - Bardon Mill 0943 - 1052 - - 1150 - - - - Haltwhistle 0950 - 1100 - - 1158 - - 1256 - Brampton 1005 - 1115 - - - - - 1311 - Wetheral 1014 - 1124 - - - - - 1320 - Carlisle a 1024 - 1134 - - 1232 - - 1330 - Middlesbrough d - 1131 - - 1230 - - 1331 - - Hartlepool d - 1201 - - 1300 - - 1401 - - Horden d - 1212 - - 1311 - - 1412 - - Sunderland d - 1230 - - 1329 - - 1430 - - Newcastle a - 1250 - - 1349 - - 1450 - - d 1235 1255 1315 1333 1355 1415 1428 1455 1515 1535 Dunston - - 1321 - - 1420 - - 1521 - MetroCentre a 1243 1302 1324 1341 1402 1424 1436 1502 1524 1543 d - 1303 - - 1403 - - 1503 - - Blaydon - - - - 1407 - - - - - Wylam - 1311 - - 1413 - - 1511 - - Prudhoe - 1315 - - 1418 - - 1515 - - Stocksfield - 1320 - - 1422 - - 1520 - - Riding Mill -

DURHAM:. Tal 64:9

TRADES DIRECTORY.] DURHAM:. TAl 64:9 Gent John, King street, Barnard Castle Hunter Thomas &Sons, 83 & 84 High )IartinMissD.74Ma.ndale rd.Sth.Stocktn. uent John, Sadbergo, Darlington street west, Sunderland Martin Peter, 32 Silver street, Stockton uent Michael, Gainford, Darlington Hunter William Lock hart, 12 Gibson Martin Robert, uParliament st.Stockton *Gent Richd.B. King st. Barnard Castle terrace, Chester road, Sunderland Martindale T.2 Market hall,HartlepoolW Gibb Alexander, I96 .Albert rd. Jarrow Hutchinson Jacob, I Mount pleasant, Mason James, Burlington buildings, Gibb Alexander, 2 Elm street, Jarrow Consett R.S.O Suffolk street, Sunderland *Gibbon Matthew, Staindrop, Darlingtn HutchinsonThos.Byers grn.Spennymoor Masterton W.9 Wellington st.Gateshead Gibbon W.2 Wesley st. Willington R.S.O HutchinsonT.Io Chester ter.Sunderla.nd Mathieson John B. Lyon street, Heb Gibson Jonn. Crawcrook, Ryton R.S.O Hutchinson Thos.22Edwardst.Stockton burn, Newcastle Gibson Stephen, 29 Ripon st. Gateshead Hutchinson Tbos. Gainford, Darlington Mawston J. Easington la. Fence Hous~s uilhespie Thomas, Cornsay, Durham Hutchinsqn Thomas, Middleton-in- Metcalfe John, 51 North rd. Darlington Gilhespy Robt. Winlaton,Blaydon R.S.O Teesdale, Darlington Miller James, ro Shakespeare street, Gilhespy Thomas, Rectory lane, Win- Hutchison Robert, 88 Newgate street, Southwick, Sunderland laton, Blaydon R.S.O · Bishop Auckland Millett Chas.46 Cuthbert st. Sth.Shields *Gilhome Wm. I79 High st. we. Sundrld JacksonJ. W~stAuckland,Bishop.Aucklnd Millican Thomas, I South st. Gateshead Gillhespy George, Boldon colliery, West Jameson M. 3 The Royalty, Sunderland Mtlls Henry, r Charles street, Jarrow Boldon, East Boldon R.S.O Jarrett D. J. -

Our Economy 2020 with Insights Into How Our Economy Varies Across Geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020

Our Economy 2020 With insights into how our economy varies across geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 2 3 Contents Welcome and overview Welcome from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, North East LEP 04 Overview from Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East LEP 05 Section 1 Introduction and overall performance of the North East economy 06 Introduction 08 Overall performance of the North East economy 10 Section 2 Update on the Strategic Economic Plan targets 12 Section 3 Strategic Economic Plan programmes of delivery: data and next steps 16 Business growth 18 Innovation 26 Skills, employment, inclusion and progression 32 Transport connectivity 42 Our Economy 2020 Investment and infrastructure 46 Section 4 How our economy varies across geographies 50 Introduction 52 Statistical geographies 52 Where do people in the North East live? 52 Population structure within the North East 54 Characteristics of the North East population 56 Participation in the labour market within the North East 57 Employment within the North East 58 Travel to work patterns within the North East 65 Income within the North East 66 Businesses within the North East 67 International trade by North East-based businesses 68 Economic output within the North East 69 Productivity within the North East 69 OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 4 5 Welcome from An overview from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East Local Enterprise Partnership North East Local Enterprise Partnership I am proud that the North East LEP has a sustained when there is significant debate about levelling I am pleased to be able to share the third annual Our Economy report.