Gender and the Contemporary Educational Canon in the UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obtaining Exam Results

Past exam certificates JMHS does not hold records of students' individual awards nor does it retain any copies of past certificates. To obtain copies of past certificates, you would need to contact the relevant awarding bodies. There are now five main awarding bodies for these qualifications operating in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Please consult the list below to see who may now have a copy of your past certificate: Old Exam Title New Awarding Body Board AEB Associated Examinations AQA (Guildford) Board Tel - Switchboard: 01483 506506 - ask for Candidates Services Records SEG Southern Examining Group Email: [email protected] Fax: 01483 455731 SEREB South East Regional Examinations Board SWExB South Western (Regional) Examinations Board ALSEB Associated Lancashire AQA (Manchester) Schools Examining Board Tel - Exam Records : 0161 953 1180 - ask for Candidates Services Records JMB Joint Matriculation Board Email: [email protected] Fax: 0161 4555 444 NEA Northern Examining Association NEAB Northern Examinations and Assessment Board NREB North Regional Examining Board NWREB North Western Regional Examining Board TWYLREB The West Yorkshire and Lindsey Regional Examinations Board YHREB Yorkshire and Humberside Regional Examinations Board NISEAC Northern Ireland School CCEA Examinations and Assessment Council Download form from the CCEA website , print out and send in hard copy, or NISEC Northern Ireland School Examinations Council Request form - asking for Exam Support - by: Post Tel - Exam Support: 02890 261200 Email: -

Kathleen Tattersall's Speech

"The Relationship of Examination Boards with Schools and Colleges: a historical perspective", Cambridge June 2008 My background I dub myself a historian but in reality I am not one for looking back, at least in my career which I began as a teacher: I taught in three schools: grammar, primary and comprehensive before joining an examination board. It's ironic that one of the motivations for my leaving a grammar school and moving into primary education was the oppressive nature of the examinations system and its impact on teaching and the curriculum. No escape these days! I found in a primary school all my faults and limitations as a teacher and moved back into my comfort zone – teaching history, as Head of Department in a newly developing comprehensive school where not just GCE O and A levels were on offer but CSE too. That was my first encounter with an examination intended – to paraphrase the 1958 Beloe Report - for the 20% of the ability range below the 20% of whom GCE O-level was designed. For the first time I assessed my students' course work with, as I recall, - but memory may do a disservice to the Board in question – very little guidance as to what I should be doing, let alone guidance on standards. What I well remember, however, is my first visitation from a course work moderator and the anxieties that provoked. Given that potted history of my teaching career of 7 and a half years, you could say that it is surprising that it ended with my move to an examination board – a CSE Board, the first of the five boards that I worked for in the next 30 years. -

I've Lost My Examination Certificates, Where Can I Get Hold of Copies?

I’ve lost my examination certificates, where can I get hold of copies? Contact the exam boards directly for replacement certificates, using the links below for further information: AQA - http://www.aqa.org.uk/contact-us/past-results-and-lost-certificates OCR - http://www.ocr.org.uk/students/lost-or-incorrect-certificates/ WJEC - http://www.wjec.co.uk/students/certificates/ Pearson / Edexcel - https://qualifications.pearson.com/en/support/Services/replacement- certificates.html Over the past twenty years a number of examination boards have merged. If you are not sure which board/s you took your examinations with or how to contact them please see the document produced by Ofqual at http://www.ofqual.gov.uk/help-and-support/94-articles/264- getting-copies-of-exam-certificates this shows how examination boards merged to form the current awarding bodies. If you still cannot remember which board/s you took your examinations with you can contact the various awarding bodies to see if they have a record of you achieving a qualification with them. If they cannot find a record of your qualification with them and therefore cannot issue confirmation they will not make any charge. Please note that there is generally a charge for issuing confirmation of qualifications and you will need to be able to prove that you are the certificate holder. If your old exam board no longer exists Check which board to contact for a replacement certificate or certified statement of results if your old board no longer exists. AQA (Education) Contact AQA if your old exam -

2 a Brief History of Policies, Practices and Issues

QCAChap2CB:QCAchap2CB 11/12/2007 17:16 Page 43 Techniques for monitoring the comparability of examination standards, edited by: Paul Newton, Jo-Anne Baird, Harvey Goldstein, Helen Patrick and Peter Tymms 2 A BRIEF HISTORY OF POLICIES, PRACTICES AND ISSUES RELATING TO COMPARABILITY Kathleen Tattersall Abstract This chapter which describes developments in education and assessment in England from the mid 19th century to the present day is in three parts: 1. the emergence of a ‘national system’ (the 1850s to the end of the Second World War) 2. the development and expansion of the system (1945 to the 1990s) 3. the emergence of a regulated system from the 1990s onwards. The role of comparability at each stage of these developments is highlighted. 1 An emerging national system of education and examinations 1.1 Overview Comparability is a fundamental requirement of England’s assessment system: between providers of the same product, qualifications, subjects, the demands of tests and tasks, between assessor judgements of students’ work and across time. Comparability is also an essential element of England’s accountability methodology and is expected to guarantee to governments, the general public, students and selectors that assessment is fair, equitable and reliable. Without assurances of equivalence between different instruments and outcomes that are used to make selections for jobs or a university place or to aid future learning, the basis of decision- making is flawed. The more intense the competition for work, places on courses or financial reward, the more intense is the pressure on the assessment system to demonstrate the steps taken to assure comparability. -

Old Exam Board Names.Xlsx

I need a replacement exam certificate (certified statement) and can remember the name of the old exam board but who do I contact now? Old name Acronym New name Associated Examinations Board AEB AQA Associated Lancashire Schools Examining Board ALSEB AQA Business Education Council BEC Pearson Business Technology Education Council BTEC Pearson East Midland Regional Examinations Board EMREB OCR Education Development International EDI Pearson Joint Committee for Business Studies and Public Administration JCBSPA Pearson Joint Matriculation Board JMB AQA London Chamber of Commerce and Industry LCCI Pearson London East Anglia Group LEAG Pearson Metropolitan and Middlesex Regional Examining Baords M&MREB Pearson Midland Examining Group MEG OCR North Western Regional Examining Board NWREB AQA Northern Examinations and Assessment Board NEAB AQA Northern Examining Association NEA AQA Oxford and Cambridge Examinations and Assessments Council OCEAC OCR Oxford and Cambridge Schools Examination Board OCSEB OCR Royal Society of Arts RSA OCR South East Regional Examinations Board SEREB AQA South Western (Regional) Examinations Board SWExB AQA Southern Examining Group SEG AQA Southern Regional Examinations Board SREB OCR Southern Universities Joint Board for Schools Examinations SUJB OCR Technician Education Council TEC Pearson University Entrance and Schools Examinations Council UESEC Pearson University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate UCLES OCR University of London Examinations and Assessments Council ULEAC Pearson University of London Schools Examination Board ULSEB Pearson University of Oxford Delegacy of Local Examinations UODLE OCR West Midlands Examinations Board WMEB OCR West Yorkshire and Lindsey Regional Examinations Board TWYLREB AQA Yorkshire and Humberside Regional Examinations Board YHREB AQA AQA: https://www.aqa.org.uk/ OCR: https://ocr.org.uk/ Pearson (also known as Edexcel): https://qualifications.pearson.com/en/home.html. -

Get a Replacement Exam Certificate

GOV.UK 1. Home (https://www.gov.uk/) 2. Education and learning (https://www.gov.uk/browse/education) 3. Apprenticeships, 14 to 19 education and training for work (https://www.gov.uk/browse/education/find-course) Get a replacement exam certificate 1. Who to contact Contact an exam board to get a replacement exam certificate or certified statement of results. You cannot get a replacement certificate for an O level, CSE, GCSE or A level - your exam board will send you a ‘certified statement of results’ instead. You can use this in place of your exam certificate, for example for a university application. Boards may give you a replacement certificate for other qualifications they offer. You may need to prove your identity and pay a fee. Find out which exam board you should contact if your old exam board no longer exists (https://www.gov.uk/replacement-exam-certificate/if-your-old-exam-board-no- longer-exists). Check with your school or college if you’re not sure which exam board holds your results. Exam boards The 5 boards in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are: Assessment and Qualifications Alliance (AQA) (https://www.aqa.org.uk/contact-us/past-results-and-lost-certificates) Council for Curriculum and Examinations Assessment (CCEA) (http://ccea.org.uk/qualifications/adminhelp/replacement_certificates) Pearson Edexcel (http://qualifications.pearson.com/en/support/Services/replacement-certificates.html) Oxford, Cambridge and RSA Exams (OCR) (http://www.ocr.org.uk/ocr-for/learners-and-parents/lost-or-incorrect-certificates/) Welsh Joint Examinations Committee (WJEC) (http://www.wjec.co.uk/students/certificates/) Contact the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) (http://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/212.html) for replacement certificates for Scottish qualifications. -

AQA Business Studies Specification B

General Certificate of Secondary Education Business Studies Specification B Special Features • Provides continuity with the AQA (NEAB) GCSE Business Studies • Choice of assessment routes • Many opportunities for generating evidence of Key Skills • A GCSE qualification that acts as a sound basis for progression to both GCE Advanced and Advanced VCE Material accompanying this Specification Specimen Papers and Mark Schemes Teachers’ Guide AQA GCSE 3133 Further copies of this specification booklet are available from: Publications Department, Stag Hill House, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7XJ Tel: 01483 302 302 Fax: 01483 503 123 or Aldon House, 39, Heald Grove, Rusholme, Manchester, M14 4NA Tel: 0161 953 1170 Fax: 0161 953 1177 or download from the AQA web site: http://www.aqa.org.uk © Assessment and Qualifications Alliance 2000 COPYRIGHT AQA retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specimen units and mark schemes/teachers’ guides. However, registered centres of AQA are permitted to copy material from this booklet for their own internal use, with the following important exception: AQA cannot give permission to centres to photocopy any material that is acknowledged to a third party even for internal use within the centre. Set and published by the Assessment and Qualifications Alliance. Printed in Great Britain by Thanet Press Ltd, Union Crescent, Margate, Kent, CT9 1NU. The Assessment and Qualifications Alliance (AQA) is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales 3644723 and a registered Charity 1073334. Registered address Addleshaw Booth & Co., Sovereign House, PO Box 8, Sovereign Street, Leeds LS1 1HQ. The AQA was formed by the merger of the Associated Examining Board (AEB)/Southern Examining Group (SEG) and the Northern Examinations and Assessment Board (NEAB). -

Examining Assessment a Compendium of Abstracts Taken from Research Conducted by AQA and Predecessor Bodies, Th

Examining Assessment Examining assessment A compendium of abstracts taken from research conducted by AQA and predecessor bodies, th published to mark the 40 anniversary of the AQA Research Committee Centre for Education Research and Practice (CERP) for Education Research Centre 40 Y E A R S ANNIVERSARY cerp.org.uk Centre for Education Research and Practice (CERP) CERP15_001, 088, spine_BWM.indd 3 12/04/2016 12:46 CERP15_002_CJv2.indd 2 08/02/2016 08:34 Examining assessment A compendium of abstracts taken from research conducted by AQA and predecessor bodies, published to mark the 40th anniversary of the AQA Research Committee Edited by Lena Gray, Claire Jackson and Lindsay Simmonds Contributors Ruth Johnson, Ben Jones, Faith Jones, Lesley Meyer, Debbie Miles, Hilary Nicholls, Anne Pinot de Moira and Martin Taylor Director Alex Scharaschkin cerp.org.uk Centre for Education Research and Practice (CERP) CERP15_003_017_CJv3.indd 3 09/02/2016 10:10 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior permission of AQA. The views expressed here are those of the authors and not of the publisher, editors, AQA or its employees. First published by the Centre for Education Research and Practice (CERP) in 2015. © AQA, Stag Hill House, Guildford, GU2 7XJ Production by Rhinegold Publishing Ltd cerp.org.uk Centre for Education Research and Practice (CERP) CERP15_003_017_CJv3.indd 4 09/02/2016 10:10 EXAMINING ASSESSMENT Contents Introduction vii A brief history of research conducted by AQA and predecessor bodies viii 1. -

AQA GCSE Business Studies Specification A

version 1.0 General Certificate of Secondary Education Business Studies 2004 Specification A This specification should be read in conjunction with: Specimen and Past Papers and Mark Schemes Examiners’ Reports Teachers’ Guide AQA GCSE 3132 This specification will be published annually on the AQA website (www.aqa.org.uk). If there are any changes to the specification, centres will be notified in print as well as on the website. The version on the website is the definitive version of the specification. © Assessment and Qualifications Alliance 2003 COPYRIGHT AQA retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specimen units and mark schemes/teachers’ guides. However, the registered centres for AQA are permitted to copy material from this specification booklet for their own internal use, with the following important exception: AQA cannot give permission to centres to photocopy any material that is acknowledged to a third party even for internal use within the centre. Set and published by the Assessment and Qualifications Alliance. Printed in Great Britain by Unwin Brothers Limited, The Gresham Press, Old Woking, Surrey, GU22 9LH. The Assessment and Qualifications Alliance (AQA) is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales 3644723 and a registered Charity 1073334. Registered address Addleshaw Booth & Co., Sovereign House, PO Box 8, Sovereign Street, Leeds LS1 1HQ. The AQA was formed by the merger of the Associated Examining Board (AEB)\Southern Examining Group (SEG) and the Northern Examinations and Assessment -

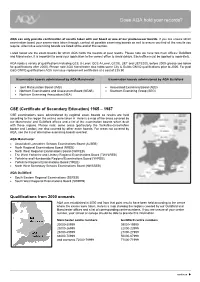

AQA CSE Exam Records

Does AQA hold your records? AQA can only provide confirmation of results taken with our board or one of our predecessor boards. If you are unsure which examination board your exams were taken through, contact all possible examining boards as well to ensure you find all the results you require. Alternative examining boards are listed at the end of this section. Listed below are the exam boards for which AQA holds the records of past results. Please note we have two main offices: Guildford and Manchester. It is important to send your application to the correct office to avoid delays. Each office must be applied to separately. AQA holds a variety of qualifications including GCE O-Level, GCE A-Level, GCSE, UET and UETESOL before 2000 (please see below for qualifications after 2000). Please note AQA Manchester also holds some City & Guilds GNVQ qualifications prior to 2000. For past C&G GNVQ qualifications AQA can issue replacement certificates at a cost of £35.90. Examination boards administered by AQA Manchester Examination boards administered by AQA Guildford • Joint Matriculation Board (JMB) • Associated Examining Board (AEB) • Northern Examinations and Assessment Board (NEAB) • Southern Examining Group (SEG) • Northern Examining Association (NEA) CSE (Certificate of Secondary Education) 1965 – 1987 CSE examinations were administered by regional exam boards so results are held according to the region the exams were taken in. Here is a map of the areas covered by our Manchester and Guildford offices and a list of the examination boards which dealt with these regions. Please note: some areas (particularly the Yorkshire-Lincolnshire border and London) are also covered by other exam boards. -

Who Holds Your Records?

Who holds your records? We hold records for exams taken with us and our predecessor boards Below is the list of our predecessor boards: JMB - Joint Matriculation Board NEAB - Northern Examinations and Assessment Board NEA - Northern Examining Association AEB - Associated Examining Board SEG - Southern Examining Group ALSEB - Association Lancashire Schools Examinations Board NREB - North Regional Examinations Board NWREB - North West Regional Examinations Board TWYLREB - The West Yorkshire and Lindsey Regional Examinations Board YHREB - Yorkshire and Humberside Regional Examinations Board YREB - Yorkshire Regional Examinations Board NWSSEB - North West Secondary Schools Examinations Board SEREB - South Eastern Regional Examinations Board SWREB - South West Regional Examinations Board. CSE (Certificate of Secondary Education) 1965 – 1987 CSE exams (1965-1987) were administered by regional exam boards, records are now held according to the area the school was based in. We can only confirm CSE results taken with our predecessor boards: Awarding Original CSE board Regions covered organisation now holding records Associated Lancashire Metropolitan Districts of Bolton, Manchester, Oldham, Rochdale and Salford and parts of Derbyshire. Also some Scottish Schools Exam Board schools. North Regional Cleveland (part) Durham and Northumberland, Districts of Gateshead, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, North Tyneside, South Examinations Board Tyneside and Sunderland. Cheshire, Lancashire, Isle of Man, Parts of Cumbria, the Metropolitan Districts of -

Getting Copies of Exam Certificates

Getting copies of exam certificates Please note that the information below applies to O level, CSE, GCSE and A level certificates only. For all other qualification types the awarding body concerned may issue a replacement certificate, at their discretion, on request. Ofqual does not hold records of students' individual awards nor does it retain any copies of past certificates. To obtain an official record of your past results you should contact the relevant awarding bodies. Please note that awarding bodies will not issue a replacement certificate but will issue a Certifying Statement of Results or a letter of confirmation of results, which will be recognised by educational institutions, professional bodies and prospective employers. There are now five main awarding bodies for these qualifications operating in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Please consult the list below to see who may now have a copy of your past O level, CSE, GCSE or A level results: Old exam Title New awarding body board AEB Associated Examinations AQA (Guildford) (opens in new window) Tel: 01483 506506 Board (Switchboard, ask for Candidates Services Records) Email: [email protected] SEG Southern Examining Group Fax: 01483 455731 SEREB South East Regional Examinations Board SWExB South Western (Regional) Examinations Board ALSEB Associated Lancashire AQA (Manchester) (opens in new window) Tel: 0161 953 1180 Schools Examining Board (Exam Records, ask for Candidates Services Records) Email: [email protected] JMB Joint Matriculation Board Fax: 0161