Politics and Planning in Residential Leeds, 1954-1979

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prison Education in England and Wales. (2Nd Revised Edition)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 388 842 CE 070 238 AUTHOR Ripley, Paul TITLE Prison Education in England and Wales. (2nd Revised Edition). Mendip Papers MP 022. INSTITUTION Staff Coll., Bristol (England). PUB DATE 93 NOTE 30p. AVAILABLE FROMStaff College, Coombe Lodge, Blagdon, Bristol BS18 6RG, England, United Kingdom (2.50 British pounds). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Correctional Education; *Correctional Institutions; Correctional Rehabilitation; Criminals; *Educational History; Foreign Countries; Postsecondary Education; Prisoners; Prison Libraries; Rehabilitation Programs; Secondary Education; Vocational Rehabilitation IDENTIFIERS *England; *Wales ABSTRACT In response to prison disturbances in England and Wales in the late 1980s, the education program for prisoners was improved and more prisoners were given access to educational services. Although education is a relatively new phenomenon in the English and Welsh penal system, by the 20th century, education had become an integral part of prison life. It served partly as a control mechanism and partly for more altruistic needs. Until 1993 the management and delivery of education and training in prisons was carried out by local education authority staff. Since that time, the education responsibility has been contracted out to organizations such as the Staff College, other universities, and private training organizations. Various policy implications were resolved in order to allow these organizations to provide prison education. Today, prison education programs are probably the most comprehensive of any found in the country. They may range from literacy education to postgraduate study, with students ranging in age from 15 to over 65. The curriculum focuses on social and life skills. -

Rachel Reeves MP

Rachel Reeves MP Monthly Report September 2014 Labour Member of Parliament for Leeds West, Shadow Secretary of State for Work & Pensions SUPPORT OUR LEEDS WEST LIBRARIES Constituency, following a number of 1000 signatures. closures in the past few years, and Leeds West now has the lowest Rachel has also hosted a public number of libraries in Leeds. For meetings at Bramley and Armley comparison, Elmet and Rothwell Library and a ‘read in’ event at Constituency has 7 Libraries. Bramley Library. A further read-in will be taking place at Armley Library on As part of the campaign, Rachel has Saturday 20th September from visited schools across Leeds West and 10am. There will be storytellers and Full crowd at Bramley Library chatted with pupils and teachers fun activities for kids. Public Meeting about their love of libraries. Armley writers, Alan Bennett and Barbara Rachel is spearheading a campaign Taylor-Bradford have sent messages against the proposed reduction of of support to the campaign, with Alan opening hours at Armley and Bennett writing, “...Every child in Bramley Libraries. Leeds today deserves these facilities and the support that I had Armley and Bramley are the only fifty years ago”. A petition against the libraries left in the Leeds West proposed cuts has received almost BRAMLEY VETERAN SECURES MEDAL Bramley war veteran Peter Paylor, Defence and was able to secure Mr age 91, has finally received his Paylor his medal after a 66 year wait. campaign medal for service in Palestine between 1945—1948, Rachel, who first met Mr Paylor at following intervention from Rachel the Bramley War Memorial and Bramley & Stanningley Councillor dedication ceremony, said, “After Kevin Ritchie. -

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

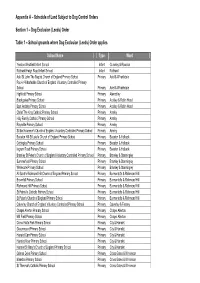

Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1

Appendix A – Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1 – Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order Table 1 – School grounds where Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order applies School Name Type Ward Yeadon Westfield Infant School Infant Guiseley & Rawdon Rothwell Haigh Road Infant School Infant Rothwell Adel St John The Baptist Church of England Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Pool-in-Wharfedale Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Highfield Primary School Primary Alwoodley Blackgates Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood East Ardsley Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood Christ The King Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Holy Family Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Raynville Primary School Primary Armley St Bartholomew's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Armley Beeston Hill St Luke's Church of England Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Cottingley Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Ingram Road Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Bramley St Peter's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Summerfield Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Whitecote Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley All Saint's Richmond Hill Church of England Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Brownhill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Richmond Hill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill St Patrick's Catholic Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill -

INSIDE a Stage Freedom to Love Utd Footy BOOKS

LEEDS 5 e ag p — t rp exce r he tc Ca INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER Spy • Amazement as Minister visits Leeds `He knows nothing' A fact finding mission to Leeds io,• students Charles Riley and by new Minister for Higher David Shelling recited their Education Robert Jackson. poems against government turned into an acute embarrass- education policy, part of their ment when it became clear that repertoire as the comedy group he was painfully uninformed on 'Codmen Inc'. the country's education situa- The 'alternative' demo was tion. organised by the Students Un- Student leaders were clearly ion to avoid the more orthodox amazed at the ministers lack of method of jeering and egg knowledge. Poly Union presi- throwing . dent Ed Gamble said. "I fear At the University no such for Higher Education with this originality was in evidence. man at the helm. He know no- Near 150 people turned up to thing." the disappointingly small demo LUU general secretary Ger- outside the great Hall, which he maine Varnay was also none visited during the afternoon. too impressed. Nominated by the Exec to meet the minister LULI administration officer and put forward the Unions Austen Earth put the low turn- opposition to reduced govern- out down to the time of year, ment funding. she left the con- "It's very difficult to motivate frontation frustrated. people at this time of year. 'He was so patronising and They're heavily involved in condescending. Predictably he their social lives." he said. didn't listen to a word I said.' Nevertheless the crowd was The day long trip was heavily able to produce an astonishing punctuated by demonstrations volume of noise on the arrival • Robert Jackson MP. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

Armley CWLT Workshop- Attendance List

Armley CWLT Workshop- Attendance List Name Organisation Attendence Sue Jones CCG Amelia Letima CCG Peter Roebuck CCG Aimee Lowdon CCG Linda Thompson Armley Practice Manager Steve Keyes Confederation Becky Barwick CCG Sinead Brannigan Patient Empowerment Link Worker, Armley Locality Dawn Newsome Armley Helping Hands Rhona Neilson LCC, Adult Social Care Anthony Kelly LCC, Adult Social Care Alison Inglehearn Leeds Community Mental Health Paul Morrin LCH Pablo Martin GP Partner- Armley Locality Oliver Bamford LCC, Team Leader One Stop Alison Lowe LCC Alice Smart Local Councillor Armley James McKenna Local Councillor Armley Peter Mudge Local Councillor Armley Julie Brier Patient Representative & Thornton Medical Practice Charlotte Batty LCC Hazel Burleigh Community Links Stuart Byrne Alison Fenton Stockhill Day Centre Jonathan Hindley LCC, Public Health Hannah Howe Forum Central Kim Johnston Leeds Beckett University Elizabeth Keat LCH, Outreach Nurse, Gypsy Traveller Community Alison Langton LCH Gill Lockwood LCH Melissa @cpwy CPWY Paul Metherington West Yorkshire Fire Service Dawn Newsome Armley Helping Hands Charlotte Orton LCC, Public Health Grace Purnell Carers Leeds Joanthan Roberts Targeted Services Leader Rachael Rutherford Leeds Teaching Hospital Victoria Savage Leeds Mental Health Eve Townsley Leeds & York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust John Wash LCH Emma Woolford LCC, Active Leeds Sharon Guy LCC Simon Betts Donna Wagner West Yorkshire Fire Service Sarah Kemp LCC, Health Partnerships Shaun Cale LCC, Public Health Helen Kemp Leeds Mind Faye Croxen CCG Rebecca Houlding New Wortley Community Centre Teressa Milligan New Wortley Community Centre Sally Miller Alison Lowe Local Councillor Armley Charlotte Batty LCC Lucy Cockrem LCC Sarah Kemp LCC Richard Poll LCC Gillian Wood LCC, Adult Social Care Julie Seymour LCC Wendy Elson NHS Janet Hamilton LCC. -

56 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

56 bus time schedule & line map 56 Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre View In Website Mode The 56 bus line (Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre: 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM (2) Moor Grange <-> Whinmoor: 5:15 AM - 10:40 PM (3) Swarcliffe <-> Moor Grange: 5:07 AM (4) Whinmoor <-> Leeds City Centre: 11:10 PM - 11:40 PM (5) Whinmoor <-> Moor Grange: 5:15 AM - 10:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 56 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 56 bus arriving. Direction: Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre 56 bus Time Schedule 26 stops Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Latchmere Drive, Moor Grange Latchmere Green, Leeds Tuesday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Latchmere Road, Moor Grange Wednesday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Old Farm Approach, Moor Grange Thursday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Friday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Old Oak Drive, West Park Old Oak Garth, Leeds Saturday 11:10 PM Beckett Park, West Park Ghyll Road, West Park 56 bus Info Woodbridge Crescent, Beckett Park Direction: Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre Stops: 26 Woodbridge Place, Beckett Park Trip Duration: 22 min Queenswood Drive, Leeds Line Summary: Latchmere Drive, Moor Grange, Latchmere Road, Moor Grange, Old Farm Approach, Queenswood Road, Beckett Park Moor Grange, Old Oak Drive, West Park, Beckett Jaques Close, Leeds Park, West Park, Ghyll Road, West Park, Woodbridge Crescent, Beckett Park, Woodbridge Place, Beckett Eden -

Leeds Municipal Offices, It Originally Housed Various the 2Nd Floor to Find out More About the Building

Arts Floor (1st floor) The Art Library was originally the lending library, with aisles and a central nave. It had terracotta columns and arches and a vaulted ceiling, covered up when the City Museum was in the building but since revealed. The book-cases were of American walnut. The side room was a small museum, only 22 square feet, containing among other exhibits a celebrated stuffed crocodile bought for 3 guineas and guaranteed not to shrink when washed! The Leeds City Police Headquarters were located in these rooms 1934-1965. Can you spot the sign for the Criminal Investigation Department, which was originally housed on the 1st floor? Information Floor (2nd floor) The Local and Family History Library was originally a reference library and remains largely unchanged, except for redecoration and carpeting. The room is 36ft high with terracotta alcoves. The oak ceiling is divided by wrought iron principals into panels, and there are mirrored panels at each end at gallery level. The 15ft-long English walnut tables are part of the original furniture. A History of Leeds A lift was first installed Central Library in 1898 to transport “There is nothing finer in architectural effort in the whole www.leeds.gov.uk/localstudies users to the of Leeds than the central hall of the building” reference – The Yorkshireman, 1884 section Central Library is a Grade II* listed building constructed 1878-1884 and designed by Leeds’ own George Corson. Opened on 17 April Visit the Local and Family History Library on 1884 as the Leeds Municipal Offices, it originally housed various the 2nd floor to find out more about the building. -

May 2021 FOI 2387-21 Drink Spiking

Our ref: 2387/21 Figures for incidents of drink spiking in your region over the last 5 years (year by year) I would appreciate it if the figures can be broken down to the nearest city/town. Can you also tell me the number of prosecutions there have been for the above offences and how many of those resulted in a conviction? Please see the attached document. West Yorkshire Police receive reports of crimes that have occurred following a victim having their drink spiked, crimes such as rape, sexual assault, violence with or without injury and theft. West Yorkshire Police take all offences seriously and will ensure that all reports are investigated. Specifically for victims of rape and serious sexual offences, depending on when the offence occurred, they would be offered an examination at our Sexual Assault Referral Centre, where forensic samples, including a blood sample for toxicology can be taken, with the victim’s consent, if within the timeframes and guidance from the Faculty for Forensic and Legal Medicine. West Yorkshire Police work with support agencies to ensure that all victims of crime are offered support through the criminal justice process, including specialist support such as from Independent Sexual Violence Advisors. Recorded crime relating to spiked drinks, 01/01/2016 to 31/12/2020 Notes Data represents the number of crimes recorded during the period which: - were not subsequently cancelled - contain the search term %DR_NK%SPIK% or %SPIK%DR_NK% within the crime notes, crime summary and/or MO - specifically related to a drug/poison/other noxious substance having been placed in a drink No restrictions were placed on the type of drink, the type of drug/poison or the motivation behind the act (i.e. -

Carlton Hill LM

Friends Meeting House, Carlton Hill 188 Woodhouse Lane, LS2 9DX National Grid Reference: SE 29419 34965 Statement of Significance A modest meeting house built in 1987 that provides interconnecting spaces which create flexible, spacious and well-planned rooms which can be used by both the Quakers and community groups. The meeting house has low architectural interest and low heritage value. Evidential value The current meeting house is a modern building with low evidential value. However, it was built on the site of an earlier building dating from the nineteenth century, and following this a tram shed. The site has medium evidential value for the potential to derive information relating to the evolution of the site. Historical value The meeting house has low historical significance as a relatively recent building, however, Woodhouse Lane provides a local context for the history of Quakers in the area from 1868. Aesthetic value This modern building has medium aesthetic value and makes a neutral contribution to the street scene. Communal value The meeting house was built for Quaker use and is also a valued community resource. The building is used by a number of local groups and visitors. Overall the building has high communal value. Part 1: Core data 1.1 Area Meeting: Leeds 1.2 Property Registration Number: 0004210 1.3 Owner: Area Meeting 1.4 Local Planning Authority: Leeds City Council 1.5 Historic England locality: Yorkshire and the Humber 1.6 Civil parish: Leeds 1.7 Listed status: Not listed 1.8 NHLE: Not applicable 1.9 Conservation Area: No 1.10 Scheduled Ancient Monument: No 1.11 Heritage at Risk: No 1.12 Date(s): 1987 1.13 Architect (s): Michael Sykes 1.14 Date of visit: 15 March 2016 1.15 Name of report author: Emma Neil 1.16 Name of contact(s) made on site: Lea Keeble 1.17 Associated buildings and sites: Detached burial ground at Adel NGR SE 26414 39353 1.18 Attached burial ground: No 1.19 Information sources: David M. -

Sport in Leeds Rugby (Generally Referred to As ‘Football’ Before the 1870S) ● the Football Essays Listed Above Cover Some Early Rugby History

● Leeds United: The Complete Record by M. Jarred and M. Macdonald (L 796.334 JAR) – Definitive study; also covers Leeds City (1904-1919). ● “Leeds United Football Club: The Formative Years 1919-1938” and “The Breakthrough Season 1964-5” – Photo-essays by D. Saffer and H. Dalphin, in Aspects of Leeds, vols. 2 & 3 (L 942.819 ASP). ● LUFC Match Day Programmes; newspaper supplements; fan magazines (e.g. The Hanging Sheep, The Peacock) – We hold various items from the 1960s to 2000s (see catalogue, under ‘Football’). Golf ● Guide to Yorkshire Golf by C. Scatchard (YP 796.352 SCA) – Potted histories of Leeds and Yorkshire golf clubs as of 1955. ● Some Yorkshire Golf Courses by Kolin Robertson (Y 796.352 ROB) – 1935 publication with descriptions of many Leeds courses, including Garforth, Horsforth, Moortown and Temple Newsam. Horse Racing ● Race Day Cards for Haigh Park Races (Leeds Race Ground) 1827-1832 (L 798.4 L517) and map of race course (ML 1823). ● A Short History of Wetherby Racecourse by J. Fairfax-Barraclough (LP W532 798). ● Sporting Days and Sporting Stories by J. Fairfax-Blakeborough (Y 798.4 BLA) – Includes various accounts of Wetherby and Leeds races Local and Family History and riders (see index of book). Research Guides Motor Sports ● Leeds Motor Club 1926 (LF 796.706 L517) – Scrapbook of newscuttings and photographs relating to motorbike and car racing. Sport in Leeds Rugby (Generally referred to as ‘football’ before the 1870s) ● The football essays listed above cover some early rugby history. Our Research Guides list some of the most useful, interesting and ● The Leeds Rugby League Story by D.