Circulatory Shock and Peripheral Circulatory Failure: a Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative

EXCLUSION CRITERIA NATIONAL CARDIOGENIC SHOCK INITIATIVE Evidence of Anoxic Brain Injury Unwitnessed out of hospital cardiac arrest or any cardiac arrest in which ROSC is not ALGORITHM achieved in 30 minutes IABP placed prior to Impella Septic, anaphylactic, hemorrhagic, and neurologic causes of shock Non-ischemic causes of shock/hypotension (Pulmonary Embolism, Pneumothorax, INCLUSION CRITERIA Myocarditis, Tamponade, etc.) Active Bleeding Acute Myocardial Infarction: STEMI or NSTEMI Recent major surgery Ischemic Symptoms Mechanical Complications of AMI EKG and/or biomarker evidence of AMI (STEMI or NSTEMI) Cardiogenic Shock Known left ventricular thrombus Hypotension (<90/60) or the need for vasopressors or inotropes to maintain systolic Patient who did not receive revascularization blood pressure >90 Contraindication to intravenous systemic anticoagulation Evidence of end organ hypoperfusion (cool extremities, oliguria, lactic acidosis) Mechanical aortic valve ACCESS & HEMODYNAMIC SUPPORT Obtain femoral arterial access (via direct visualization with use of ultrasound and fluoro) Obtain venous access (Femoral or Internal Jugular) ACTIVATE CATH LAB Obtain either Fick calculated cardiac index or LVEDP IF LVEDP >15 or Cardiac Index < 2.2 AND anatomy suitable, place IMPELLA Coronary Angiography & PCI Attempt to provide TIMI III flow in all major epicardial vessels other than CTO If unable to obtain TIMI III flow, consider administration of intra-coronary ** QUALITY MEASURES ** vasodilators Impella Pre-PCI Door to Support Time Perform Post-PCI Hemodynamic Calculations < 90 minutes 1. Cardiac Power Output (CPO): MAP x CO Establish TIMI III Flow 451 Right Heart Cath 2. Pulmonary Artery Pulsatility Index (PAPI): sPAP – dPAP Wean off Vasopressors & RA Inotropes Maintain CPO >0.6 Watts Wean OFF Vasopressors and Inotropes Improve survival to If CPO is >0.6 and PAPI >0.9, operators should wean vasopressors and inotropes and determine if Impella can be weaned and removed in the Cath Lab or left in place with transfer to ICU. -

Ready, Set, (Vaso)Action! Vasoactive Agents for Catecholamine Refractory

Lights, Camera, (Vaso)Action! Vasoactive Agents for Catecholamine Refractory Septic Shock Gregory Kelly, Pharm.D. PGY2 Emergency Medicine Pharmacy Resident University of Rochester Medical Center October 28, 2017 Conflicts of Interest I have no conflicts of interest to disclose Presentation Objectives 1. Discuss the currently available literature evaluating angiotensin II as a treatment modality for septic shock. 2. Interpret the results of the ATHOS-3 trial and its applicability to the management of patients with septic shock. Vasopressin Vasopressin: A History Case series of vasopressin First case report deficiency in in severe shock septic shock 1960-80’s 1954 1957 1997 2003 Vasopressin Use of First RCT first vasopressin for suggesting synthesized GI superiority of hemorrhage, vasopressin + diabetes norepinephrine to insipidus and norepinephrine ileus alone Matis-Gradwohl I, et al. Crit Care. 2013;17:1002. VAAST Trial: design VASST Trial Design Mutlicenter, international, randomized, double-blind trial • n = 778 Population • Refractory septic shock Intervention Vasopressin 0.01-0.03 units/min vs. Norepinephrine alone Russell JA, et al. New Engl J Med. 2008;358:877-87. Drug Titration Vasopressin start at 0.01 units/min Titrate by 0.005 units/min Every 10 minutes to reach max of 0.03 units/min MAP ≥65-70mmHg MAP <65-70mmHg Decrease Increase norepinephrine by norepinephrine 1-2 mcg/min every 5-10 minutes Russell JA, et al. New Engl J Med. 2008;358:877-87. Norepinephrine Requirements Norepinephrine Vasopressin Russell JA, et al. New Engl J Med. 2008;358:877-87. Mortality 450 Day 28 Day 90 400 P = 0.27 P = 0.10 350 300 250 200 150 Patients Alive Patients 100 50 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 Days Since Drug Initiation Vasopressin Norepinephrine Russell JA, et al. -

What Is Sepsis?

What is sepsis? Sepsis is a serious medical condition resulting from an infection. As part of the body’s inflammatory response to fight infection, chemicals are released into the bloodstream. These chemicals can cause blood vessels to leak and clot, meaning organs like the kidneys, lung, and heart will not get enough oxygen. The blood clots can also decrease blood flow to the legs and arms leading to gangrene. There are three stages of sepsis: sepsis, severe sepsis, and ultimately septic shock. In the United States, there are more than one million cases with more than 258,000 deaths per year. More people die from sepsis each year than the combined deaths from prostate cancer, breast cancer, and HIV. More than 50 percent of people who develop the most severe form—septic shock—die. Septic shock is a life-threatening condition that happens when your blood pressure drops to a dangerously low level after an infection. Who is at risk? Anyone can get sepsis, but the elderly, infants, and people with weakened immune systems or chronic illnesses are most at risk. People in healthcare settings after surgery or with invasive central intravenous lines and urinary catheters are also at risk. Any type of infection can lead to sepsis, but sepsis is most often associated with pneumonia, abdominal infections, or kidney infections. What are signs and symptoms of sepsis? The initial symptoms of the first stage of sepsis are: A temperature greater than 101°F or less than 96.8°F A rapid heart rate faster than 90 beats per minute A rapid respiratory rate faster than 20 breaths per minute A change in mental status Additional symptoms may include: • Shivering, paleness, or shortness of breath • Confusion or difficulty waking up • Extreme pain (described as “worst pain ever”) Two or more of the symptoms suggest that someone is becoming septic and needs immediate medical attention. -

Update on Volume Resuscitation Hypovolemia and Hemorrhage Distribution of Body Fluids Hemorrhage and Hypovolemia

11/7/2015 HYPOVOLEMIA AND HEMORRHAGE • HUMAN CIRCULATORY SYSTEM OPERATES UPDATE ON VOLUME WITH A SMALL VOLUME AND A VERY EFFICIENT VOLUME RESPONSIVE PUMP. RESUSCITATION • HOWEVER THIS PUMP FAILS QUICKLY WITH VOLUME LOSS AND IT CAN BE FATAL WITH JUST 35 TO 40% LOSS OF BLOOD VOLUME. HEMORRHAGE AND DISTRIBUTION OF BODY FLUIDS HYPOVOLEMIA • TOTAL BODY FLUID ACCOUNTS FOR 60% OF LEAN BODY WT IN MALES AND 50% IN FEMALES. • BLOOD REPRESENTS ONLY 11-12 % OF TOTAL BODY FLUID. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF HYPOVOLEMIA • SUPINE TACHYCARDIA PR >100 BPM • SUPINE HYPOTENSION <95 MMHG • POSTURAL PULSE INCREMENT: INCREASE IN PR >30 BPM • POSTURAL HYPOTENSION: DECREASE IN SBP >20 MMHG • POSTURAL CHANGES ARE UNCOMMON WHEN BLOOD LOSS IS <630 ML. 1 11/7/2015 INFLUENCE OF ACUTE HEMORRHAGE AND FLUID RESUSCITATION ON BLOOD VOLUME AND HCT • COMPARED TO OTHERS, POSTURAL PULSE INCREMENT IS A SENSITIVE AND SPECIFIC MARKER OF ACUTE BLOOD LOSS. • CHANGES IN HEMATOCRIT SHOWS POOR CORRELATION WITH BLOOD VOL DEFICITS AS WITH ACUTE BLOOD LOSS THERE IS A PROPORTIONAL LOSS OF PLASMA AND ERYTHROCYTES. MARKERS FOR VOLUME CHEMICAL MARKERS OF RESUSCITATION HYPOVOLEMIA • CVP AND PCWP USED BUT EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES HAVE SHOWN A POOR CORRELATION BETWEEN CARDIAC FILLING PRESSURES AND VENTRICULAR EDV OR CIRCULATING BLOOD VOLUME. Classification System for Acute Blood Loss • MORTALITY RATE IN CRITICALLY ILL PATIENTS Class I: Loss of <15% Blood volume IS NOT ONLY RELATED TO THE INITIAL Compensated by transcapillary refill volume LACTATE LEVEL BUT ALSO THE RATE OF Resuscitation not necessary DECLINE IN LACTATE LEVELS AFTER THE TREATMENT IS INITIATED ( LACTATE CLEARANCE ). Class II: Loss of 15-30% blood volume Compensated by systemic vasoconstriction 2 11/7/2015 Classification System for Acute Blood FLUID CHALLENGES Loss Cont. -

Septic Shock Management Guided by Ultrasound: a Randomized Control Trial (SEPTICUS Trial)

Septic Shock Management Guided by Ultrasound: A Randomized Control Trial (SEPTICUS Trial) RESEARCH PROTOCOL dr. Saptadi Yuliarto, Sp.A(K), MKes PEDIATRIC EMERGENCY AND INTENSIVE THERAPY SAIFUL ANWAR GENERAL HOSPITAL, MALANG MEDICAL FACULTY OF BRAWIJAYA UNIVERSITY DECEMBER 30, 2020 1 SUMMARY Research Title Septic Shock Management Guided by Ultrasound: A Randomized Control Trial (SEPTICUS Trial) Research Design A multicentre experimental study in pediatric patients with a diagnosis of septic shock. Research Objective To examine the differences in fluid resuscitation outcomes for septic shock patients with the USSM and mACCM protocols • Patient mortality rate • Differences in clinical parameters • Differences in macrocirculation hemodynamic parameters • Differences in microcirculation laboratory parameters Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria Inclusion: Pediatric patients (1 month - 18 years old), diagnosed with septic shock Exclusion: patients with congenital heart defects, already receiving fluid resuscitation or inotropic-vasoactive drugs prior to study recruitment, patients after cardiac surgery Research Setting A multicenter study conducted in all pediatric intensive care units (HCU / PICU), emergency department (IGD), and pediatric wards in participating hospitals in Indonesia. Sample Size Calculating the minimum sample size using the clinical trial formula for the mortality rate, obtained a sample size of 340 samples. Research Period The study was carried out in the period January 2021 to December 2022 Data Collection Process Pediatric patients who met the study inclusion criteria were randomly divided into 2 groups, namely the intervention group (USSM protocol) or the control group (mACCM protocol). Patients who respond well to resuscitation will have their outcome analyzed in the first hour (15-60 minutes). Patients with fluid refractory shock will have their output analyzed at 6 hours. -

Vasopressin, Norepinephrine, and Vasodilatory Shock After Cardiac Surgery Another “VASST” Difference?

Vasopressin, Norepinephrine, and Vasodilatory Shock after Cardiac Surgery Another “VASST” Difference? James A. Russell, A.B., M.D. AJJAR et al.1 designed, Strengths of VANCS include H conducted, and now report the blinded randomized treat- in this issue an elegant random- ment, careful follow-up, calcula- ized double-blind controlled trial tion of the composite outcome, of vasopressin (0.01 to 0.06 U/ achieving adequate and planned Downloaded from http://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-pdf/126/1/9/374893/20170100_0-00010.pdf by guest on 01 October 2021 min) versus norepinephrine (10 to sample size, and evaluation of 60 μg/min) post cardiac surgery vasopressin pharmacokinetics. with vasodilatory shock (Vaso- Nearly 20 yr ago, Landry et al.2–6 pressin versus Norepinephrine in discovered relative vasopressin defi- Patients with Vasoplegic Shock ciency and benefits of prophylactic After Cardiac Surgery [VANCS] (i.e., pre cardiopulmonary bypass) trial). Open-label norepinephrine and postoperative low-dose vaso- was added if there was an inad- pressin infusion in patients with equate response to blinded study vasodilatory shock after cardiac drug. Vasodilatory shock was surgery. Previous trials of vasopres- defined by hypotension requiring sin versus norepinephrine in cardiac vasopressors and a cardiac index surgery were small and underpow- greater than 2.2 l · min · m-2. The “[The use of] …vasopressin ered for mortality assessment.2–6 primary endpoint was a compos- Vasopressin stimulates arginine ite: “mortality or severe complica- infusion for treatment of vasopressin receptor 1a, arginine tions.” Patents with vasodilatory vasodilatory shock after vasopressin receptor 1b, V2, oxy- shock within 48 h post cardiopul- tocin, and purinergic receptors monary bypass weaning were eli- cardiac surgery may causing vasoconstriction (V1a), gible. -

Septic, Hypovolemic, Obstructive and Cardiogenic Killers

S.H.O.C.K Septic, Hypovolemic, Obstructive and Cardiogenic Killers Jason Ferguson, BPA, NRP Public Safety Programs Head, CVCC Amherst County DPS, Paramedic Centra One, Flight Paramedic Objectives • Define Shock • Review patho and basic components of life • Identify the types of shock • Identify treatments Shock Defined • “Rude unhinging of the machinery of life”- Samuel Gross, U.S. Trauma Surgeon, 1962 • “A momentary pause in the act of death”- John Warren, U.S. Surgeon, 1895 • Inadequate tissue perfusion Components of Life Blood Flow Right Lungs Heart Left Body Heart Patho Review • Preload • Afterload • Baroreceptors Perfusion Preservation Basic rules of shock management: • Maintain airway • Maintain oxygenation and ventilation • Control bleeding where possible • Maintain circulation • Adequate heart rate and intravascular volume ITLS Cases Case 1 • 11 month old female “not acting right” • Found in crib this am lethargic • Airway patent • Breathing is increased; LS clr • Circulation- weak distal pulses; pale and cool Case 1 • VS: RR 48, HR 140, O2 98%, Cap refill >2 secs • Foul smelling diapers x 1 day • “I must have changed her two dozen times yesterday” • Not eating or drinking much Case 1 • IV established after 4 attempts • Fluid bolus initiated • Transported to ED • Received 2 liters of fluid over next 24 hours Hypovolemic Shock Hemorrhage Diarrhea/Vomiting Hypovolemia Burns Peritonitis Shock Progression Compensated to decompensated • Initial rise in blood pressure due to shunting • Initial narrowing of pulse pressure • Diastolic raised -

Vasodilatory Shock in the ICU and the Role of Angiotensin II

REVIEW CURRENT OPINION Vasodilatory shock in the ICU and the role of angiotensin II Brett J. Wakefielda, Gretchen L. Sachab, and Ashish K. Khannaa,c Purpose of review There are limited vasoactive options to utilize for patients presenting with vasodilatory shock. This review discusses vasoactive agents in vasodilatory, specifically, septic shock and focuses on angiotensin II as a novel, noncatecholamine agent and describes its efficacy, safety, and role in the armamentarium of vasoactive agents utilized in this patient population. Recent findings The Angiotensin II for the Treatment of High-Output Shock 3 study evaluated angiotensin II use in patients with high-output, vasodilatory shock and demonstrated reduced background catecholamine doses and improved ability to achieve blood pressure goals associated with the use of angiotensin II. A subsequent analysis showed that patients with a higher severity of illness and relative deficiency of intrinsic angiotensin II and who received angiotensin II had improved mortality rates. In addition, a systematic review showed infrequent adverse reactions with angiotensin II demonstrating its safety for use in patients with vasodilatory shock. Summary With the approval and release of angiotensin II, a new vasoactive agent is now available to utilize in these patients. Overall, the treatment for vasodilatory shock should not be a one-size fits all approach and should be individualized to each patient. A multimodal approach, integrating angiotensin II as a noncatecholamine option should be considered for patients presenting with this disease state. Keywords angiotensin II, catecholamines, septic shock, vasodilatory shock, vasopressors INTRODUCTION vasoactive agents, if needed, to augment hemody- Vasodilatory shock is the most common form of namics [6]. -

209360Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 209360Orig1s000 RISK ASSESSMENT and RISK MITIGATION REVIEW(S) Division of Risk Management (DRISK) Office of Medication Error Prevention and Risk Management (OMEPRM) Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology (OSE) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Application Type NDA Application Number 209360 PDUFA Goal Date February 28, 2018 OSE RCM # 2017-1333 Reviewer Name(s) Theresa Ng, Pharm.D, BCPS, CDE Team Leader Leah Hart, Pharm.D Deputy Division Director Jamie Wilkins Parker, Pharm.D Review Completion Date December 19, 2017 Subject Evaluation of Need for a REMS Established Name LJPC-501 Name of Applicant La Jolla Pharmaceutical Company (La Jolla) Therapeutic Class Angiotensin II (vasoactive) (b) (4) Formulation(s) 2.5 mg/ml and 5 mg vials for Intravenous Injection Dosing Regimen 20 ng/kg/min titrated as frequently as every 5 minutes by increments of (b) (4) ng/kg/min as needed to maintain targeted blood pressure, not to exceed 80 ng/kg/min during the first 3 hours. Maintenance dose should not exceed 40 ng/kg/min 1 Reference ID: 4197230 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Background ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

Recognizing and Treating Shock in the Prehospital Setting

9/3/2020 Recognizing and Treating Shock in the Prehospital Setting 1 9/3/2020 Special Thanks to Our Sponsor 2 9/3/2020 Your Presenters Dr. Raymond L. Fowler, Dr. Melanie J. Lippmann, MD, FACEP, FAEMS MD FACEP James M. Atkins MD Distinguished Professor Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine of Emergency Medical Services, Brown University Chief of the Division of EMS Alpert Medical School Department of Emergency Medicine Attending Physician University of Texas Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital Southwestern Medical Center Providence, RI Dallas, TX 3 9/3/2020 Scenario SHOCK INDEX?? Pulse ÷ Systolic 4 9/3/2020 What is Shock? Shock is a progressive state of cellular hypoperfusion in which insufficient oxygen is available to meet tissue demands It is key to understand that when shock occurs, the body is in distress. The shock response is mounted by the body to attempt to maintain systolic blood pressure and brain perfusion during times of physiologic distress. This shock response can accompany a broad spectrum of clinical conditions that stress the body, ranging from heart attacks, to major infections, to allergic reactions. 5 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Shock may be caused when oxygen intake, absorption, or delivery fails, or when the cells are unable to take up and use the delivered oxygen to generate sufficient energy to carry out cellular functions. 6 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Hypovolemic Shock Distributive Shock Inadequate circulating fluid leads A precipitous increase in vascular to a diminished cardiac output, capacity as blood vessels dilate and which results in an inadequate the capillaries leak fluid, translates into delivery of oxygen to the too little peripheral vascular resistance tissues and cells and a decrease in preload, which in turn reduces cardiac output 7 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Cardiogenic Shock Obstructive Shock The heart is unable to circulate Obstruction to the forward flow of sufficient blood to meet the blood exists in the great vessels metabolic needs of the body. -

Cardiac Shock-Wave Therapy in the Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease

Burneikaitė et al. Cardiovascular Ultrasound (2017) 15:11 DOI 10.1186/s12947-017-0102-y REVIEW Open Access Cardiac shock-wave therapy in the treatment of coronary artery disease: systematic review and meta-analysis Greta Burneikaitė1,2,7*, Evgeny Shkolnik3,4, Jelena Čelutkienė1,2*, Gitana Zuozienė1,2, Irena Butkuvienė1,2, Birutė Petrauskienė1,2, Pranas Šerpytis1,2, Aleksandras Laucevičius1,5 and Amir Lerman6 Abstract Aim: To systematically review currently available cardiac shock-wave therapy (CSWT) studies in humans and perform meta-analysis regarding anti-anginal efficacy of CSWT. Methods: The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, Medline, Medscape, Research Gate, Science Direct, and Web of Science databases were explored. In total 39 studies evaluating the efficacy of CSWT in patients with stable angina were identified including single arm, non- and randomized trials. Information on study design, subject’s characteristics, clinical data and endpoints were obtained. Assessment of publication risk of bias was performed and heterogeneity across the studies was calculated by using random effects model. Results: Totally, 1189 patients were included in 39 reviewed studies, with 1006 patients treated with CSWT. The largest patient sample of single arm study consisted of 111 patients. All selected studies demonstrated significant improvement in subjective measures of angina symptoms and/or quality of life, in the majority of studies left ventricular function and myocardial perfusion improved. In 12 controlled studies with 483 patients included (183 controls) angina class, Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) score, nitrates consumption were significantly improved after the treatment. In 593 participants across 22 studies the exercise capacity was significantly improved after CSWT, as compared with the baseline values (in meta-analysis standardized mean difference SMD = −0.74; 95% CI, −0.97 to −0.5; p < 0.001). -

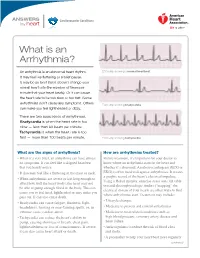

What Is an Arrhythmia?

ANSWERS Cardiovascular Conditions by heart What is an Arrhythmia? An arrhythmia is an abnormal heart rhythm. ECG strip showing a normal heartbeat It may feel like fluttering or a brief pause. It may be so brief that it doesn’t change your overall heart rate (the number of times per minute that your heart beats). Or it can cause the heart rate to be too slow or too fast. Some arrhythmias don’t cause any symptoms. Others ECG strip showing bradycardia can make you feel lightheaded or dizzy. There are two basic kinds of arrhythmias. Bradycardia is when the heart rate is too slow — less than 60 beats per minute. Tachycardia is when the heart rate is too fast — more than 100 beats per minute. ECG strip showing tachycardia What are the signs of arrhythmia? How are arrhythmias treated? • When it’s very brief, an arrhythmia can have almost Before treatment, it’s important for your doctor to no symptoms. It can feel like a skipped heartbeat know where an arrhythmia starts in the heart and that you barely notice. whether it’s abnormal. An electrocardiogram (ECG or • It also may feel like a fluttering in the chest or neck. EKG) is often used to diagnose arrhythmias. It creates a graphic record of the heart’s electrical impulses. • When arrhythmias are severe or last long enough to Using a Holter monitor, exercise stress tests, tilt table affect how well the heart works, the heart may not test and electrophysiologic studies (“mapping” the be able to pump enough blood to the body.