Model Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA RELEASE Thomas Demand 'Daily Show' 26 September – 13

MEDIA RELEASE Thomas Demand ‘Daily Show’ 26 September – 13 December 2015 21 Woodlands Terrace, Glasgow, G3 6DF Exhibition preview on Friday 25 September, 6 - 8pm Exhibition open: Wednesday – Sunday 12pm – 5pm, until 7pm on Thursday and by appointment. The Common Guild is delighted to announce its next exhibition of 2015: a new solo presentation by renowned German artist, Thomas Demand, one of the most distinctive artists of his generation. The exhibition will include new and recent works from Demand’s series ‘The Dailies’, presented in an installation devised specially for the particular nature of the spaces at The Common Guild and involving a new wallpaper. ‘The Dailies’ is a project that calls to mind the extent to which photography has in recent times become a commonplace, daily and social pursuit – a note-taking, diary-like practice for so many. While the exhibition as a whole prompts questions about the compulsion to make images as well as the contemporary relevance and use of photography. ‘Daily Show’ is an exhibition that sits resolutely in the context of the exponential growth in online image sharing, which now sees thousands of images uploaded to social media sites every second. Demand’s works have often been based on images in widespread circulation, whether in mainstream news media or online, what critic Hal Foster has aptly described as “our shared media memory”. They have included many significant scenes, from the Oval Office to Saddam Hussein’s last hiding place. ‘The Dailies’, however, find their origins in less historic places: for each is based on a photograph taken on Demand’s mobile phone. -

Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate

For publication on or after Monday, March 29, 2010 Media Kit announcing the 2010 PritzKer architecture Prize Laureate This media kit consists of two booklets: one with text providing details of the laureate announcement, and a second booklet of photographs that are linked to downloadable high resolution images that may be used for printing in connection with the announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The photos of the Laureates and their works provided do not rep- resent a complete catalogue of their work, but rather a small sampling. Contents Previous Laureates of the Pritzker Prize ....................................................2 Media Release Announcing the 2010 Laureate ......................................3-5 Citation from Pritzker Jury ........................................................................6 Members of the Pritzker Jury ....................................................................7 About the Works of SANAA ...............................................................8-10 Fact Summary .....................................................................................11-17 About the Pritzker Medal ........................................................................18 2010 Ceremony Venue ......................................................................19-21 History of the Pritzker Prize ...............................................................22-24 Media contact The Hyatt Foundation phone: 310-273-8696 or Media Information Office 310-278-7372 Attn: Keith H. Walker fax: 310-273-6134 8802 Ashcroft Avenue e-mail: [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90048-2402 http:/www.pritzkerprize.com 1 P r e v i o u s L a u r e a t e s 1979 1995 Philip Johnson of the United States of America Tadao Ando of Japan presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. presented at the Grand Trianon and the Palace of Versailles, France 1996 1980 Luis Barragán of Mexico Rafael Moneo of Spain presented at the construction site of The Getty Center, presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. -

DAN PERJOVSCHI to CREATE SITE-SPECIFIC WALL DRAWING for Moma’S PROJECTS SERIES

DAN PERJOVSCHI TO CREATE SITE-SPECIFIC WALL DRAWING FOR MoMA’S PROJECTS SERIES Drawings on Atrium Wall Will Reflect Current Social and Political Events Projects 85: Dan Perjovschi WHAT HAPPENED TO US? May 2–August 27, 2007 The Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium, second floor NEW YORK, April 11, 2007—The Museum of Modern Art presents Projects 85: Dan Perjovschi, WHAT HAPPENED TO US?, a site-specific wall drawing for the east wall of The Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium, as part of the Museum’s ongoing Projects series. For his first solo museum exhibition in the United States, Perjovschi (Romanian, b. 1961)—who has transformed the medium of drawing, making it an object, a performance, and an installation—will spontaneously draw witty and incisive social and political images in response to current events, allowing global and local affairs to inform the final result. Beginning on April 19, he will start drawing on the wall while the Museum is open to the public, allowing visitors to observe the creation of the work. The project is accompanied by a free newspaper created by the artist. A discussion with the artist about his work will be held on April 25 in The Celeste Bartos Theater. Projects 85, on view May 2 through August 27, is organized by Roxana Marcoci, Curator, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art. “Perjovschi’s sketches and skits portray reality with a sense of criticality and pointed humor. Using concise phrases and wordplay, he employs textual puns in his work. This is clear in the work's rhetorical title, WHAT HAPPENED TO US?, in which ‘US’ may refer to either the pronoun ‘us’ or the noun ‘United States of America’,” states Ms. -

Thomas Demand

How to create an impactful side project: Get your tickets for May’s Nicer Tuesdays Online! How to create an impactful side project: Get your tickets for May’s Nicer Tuesdays Online! Championing Creativity Search for something Categories Since 2007 Words Ruby Boddington Photography Damien “My pictures give you an image of Maloney — your future memory”: Thomas 20 May 2019 10 minute read Demand in conversation with It’s In Conversation Nice That Features Art Photography Portrait Sculpture Welcome to the first of our brand new series, In Conversation, a new fortnightly interview with a leading light from the world of creativity. Every other Monday, we’ll publish a new Q&A here on It’s Nice That. Today, for the first instalment, we sent our writer Ruby Boddington to Paris to meet the Los Angeles-based German artist Thomas Demand. “The Louvre, the Centre Pompidou, these galleries are all great but places like Palais de Tokyo are the most exciting. And it has a great bookshop.” This was what Thomas Demand told me to do with my afternoon in Paris after our interview at the city’s Hôtel Lutetia. “What about the Eiffel Tower?” I asked. He responded: “It looks the same as in the photos.” It’s a particularly funny comment coming from Thomas Demand, a man whose work is concerned with exactly that: making things look, in photographs, exactly the same as they do in real life. A German-born sculptor and photographer who now splits his time between Berlin and Los Angeles, Thomas recreates famous scenes from current affairs, to scale and in breathtaking detail and accuracy – entirely out of paper. -

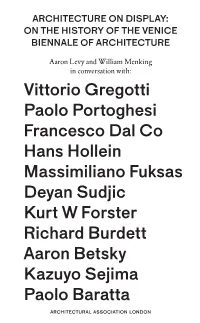

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Gagosian Gallery

Artforum January, 2000 GAGOSIAN 1999 Carnegie International Carnegie Museum of Art Katy Siegel When you walk into the lobby of the Carnegie Museum, the program of this year’s International announces itself in microcosm. There in front of you is atmospheric video projection (Diana Thater), a deadpan disquisition on the nature of representation (Gregor Schneider’s replication of his home), a labor-intensive, intricate installation (Suchan Kinoshita), a bluntly phenomenological sculpture (Olafur Eliasson), and flat, icy painting (Alex Katz). Undoubtedly the best part of the show, the lobby is also an archi-tectural site of hesitation, a threshold. Here the installation encapsulates the exhi-bition’s sense of historical suspen-sion, another kind of hesitation. Ours is a time not of endings but of pause. My favorite work, viewed through the museum’s huge glass wall, was the Eliasson, a fountain of steam wafting vertically from an expanse of water on a platform through which trees also rise up. It’s a heart-throbbing romantic landscape. Romantic, but not naive: The work plays on the tradition of the courtyard fountain, and the steam is piped from the museum’s heating system. Combining the natural and the industrial in a way peculiarly appro-priate to Pittsburgh on a quiet Sunday morning in early autumn, it echoed two billows of steam (or, more queasily, smoke?) off in the distance. When blunt physical fact achieves this kind of lyricism, it is something to see. Upstairs in the galleries, Ernesto Neto’s Nude Plasmic, 1999, relies as well on the phenomenology of simple form, but the Brazilian artist avoids Eliasson’s picturesque imagery. -

Michael Anastassiades

Michael Anastassiades “Silver Tongued” Dates: Mar 29 – Jun 30, 2019 Location: SHOP Taka Ishii Gallery, Hong Kong Opening Reception: March 29, 6-8pm; Art Brunch: March 30, 9am-12pm SHOP Taka Ishii Gallery is pleased to announce a solo exhibition from March 29 to June 30 of new works by Michael Anastassiades. This exhibition is his first in Hong Kong and second with the gallery. Having been working for more than 20 years in lighting and furniture design, Michael Anastassiades is known for his unique aesthetic highly appraised in both fine art and industrial design. Designs such as “Mobile Chandelier” and “String Lights” have remarked his leading role in the field. His design philosophy is to preserve the inherent qualities of a given material. Through his practice, he aims to provoke dialogue, participation and interaction. Between light and shadow, form and stasis, object and space, Anastassiades’ works are at once disciplined and obsessive with a playfulness that inspires a vitality one might not expect. The new exhibition will display lighting and furniture pieces designed specifically for the space. Two pendant lights “Down the Line” and “In Between the Lines” in Anastassiades’ signature material of brass, feature linear representations with lighting in nearly 275cm height. “Blah Blah” and “Blah Blah Blah” serve as curvilinear hook-shaped objects coming out of the wall. The stools “Horafia, Kastellorizo” are the result of the designer’s intriguing encounter with a cut section of a date tree. Found during one of Anastassiades’ regular hikes on Kastellorizo, the tree sections were placed on the side of the road by a boat propped up on sills while on repair. -

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a Short Story by Jeffrey Eugenides

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides Author Marcoci, Roxana Date 2005 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870700804 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/116 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art museumof modern art lIOJ^ArxxV^ 9 « Thomas Demand Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides The Museum of Modern Art, New York Published in conjunction with the exhibition Thomas Demand, organized by Roxana Marcoci, Assistant Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 4-May 30, 2005 The exhibition is supported by Ninah and Michael Lynne, and The International Council, The Contemporary Arts Council, and The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. This publication is made possible by Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro. Produced by the Department of Publications, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Edited by Joanne Greenspun Designed by Pascale Willi, xheight Production by Marc Sapir Printed and bound by Dr. Cantz'sche Druckerei, Ostfildern, Germany This book is typeset in Univers. The paper is 200 gsm Lumisilk. © 2005 The Museum of Modern Art, New York "Photographic Memory," © 2005 Jeffrey Eugenides Photographs by Thomas Demand, © 2005 Thomas Demand Copyright credits for certain illustrations are cited in the Photograph Credits, page 143. Library of Congress Control Number: 2004115561 ISBN: 0-87070-080-4 Published by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019-5497 (www.moma.org) Distributed in the United States and Canada by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, New York Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Thames & Hudson Ltd., London Front and back covers: Window (Fenster). -

Andreas Gursky's Monumental Photographs: the Media Nowa

JUST WHAT IS IT THAT MAKES GURSKY’S PHOTOS SO DIFFERENT, SO APPEALING? 1 ON ANDREAS GURSKY’S PICTORIAL STRATEGY AND THE EMBLEMATIC NATURE OF HIS ARCHITECTURAL PHOTOGRAPHS RALF BEIL 2 Andreas Gursky’s monumental photographs: The media nowa - phy have since then never stood still. Is it also just coincidence approach whose intention is nothing less than to find the one, Frankfurt, 2007), exchanges ( Tokyo Stock Exchange, 1990; Hong days uses them as eye-catchers (fig. 1); avant-garde scholars use that Thomas Demand’s C-print Wand (Mural), made in 1999 (fig. universal image that contains in compressed form all the values Kong Stock Exchange, 1994; Chicago Board of Trade I, 1997; 15 them as pictorial arguments to strengthen their thrust when diag - 3), serves as eye-catcher in the artist’s home, a loft designed by of civilized existence.” Chicago Board of Trade II, 1999; Kuwait Stock Exchange, 2007), 3 nosing today. 2 His works precisely reflect the spirit of the age. But architects Herzog & De Meuron? hotel complexes ( Atlanta, 1996; Times Square, 1997; San Fran - what is it that makes them what they are? And makes them so Gursky always has his eye on the world, seeking to transpose the ARCHITECTURE AS THEME AND SYMPTOM cisco, 1998; Shanghai, 2000; Avenue of the Americas, 2001), lux - different? What is it that makes them important, given the model abstraction into the reality of images: He is the peintre de la The compression of the issues and the values of civilized exis - ury business ( Prada I, 1996; Prada II, 1997; Ohne Titel V [Unti - tremendous amount of image data available in an “age of total vie moderne of the global age. -

400 Buildings 230 Architects 6 Geographical Regions 80 Countries a U R P E Or Am S Ica Fr a Ce Ia

400 Buildings 100 single houses┆53 schools┆21 art galleries 66 museums┆7 swimming pools┆2 town halls 230 Architects 52 office buildings┆33 unibersities┆5 international 6 Geographical Regions airports21 libraries┆5 embassies┆30 hotels 5 railway staions 80 Countries 80Architects dings Buil 125 ia As O ce an ZAHA HADID ARCHITECTS//OMA//FUKSAS//ASYMPTOTE ARCHITECTURE//ANDRÉS ia 6 5 PEREA ARCHITECT//SNØHETTA//BERNARD TSCHUMI//COOP HIMMELB(L)AU//FOSTER + B u i ld in g PARTNERS//UNStudio//laN+//KISHO KUROKAWA ARCHITECT AND ASSOCIATES//STEVEN s s t c e 8 it 0 h A c r HOLL ARCHITECTS//JOHN PORTMAN & ASSOCIATES//3DELUXE//TADAO ANDO ARCHITECT r c A h 0 it e 8 c t s & ASSOCIATES//MVRDV//SAUCIER + PERROTTE ARCHITECTES//ACCONCI STUDIO// s g n i d l i DRIENDL*ARCHITECTS//OGRYDZIAK / PRILLINGER ARCHITECTS//URBAN ENVIRONMENTS u B 5 0 ARCHITECTS//ORTLOS SPACE ENGINEERING//MOSHE SAFDIE AND ASSOCIATES INC.// 2 LOMA //JENSEN & SKODVIN ARKITEKTKONTOR AS+ARNE HENRIKSEN ARKITEKTER AS + e p o C-V HØLMEBAKK ARKITEKT//HENN ARCHITEKTEN//GIENCKE & COMPANY//CHETWOODS r u E A ARCHITECTS//AAARCHITECTEN//ABALOS+SENTKIEWICZ ARQUITECTOS//VARIOUS f r i ARCHITECTS//DENTON CORKER MARSHALL//SAMYN AND PARTNERS//ANTOINE PREDOCK// c a FREE Fernando Romero...... 3 5 s B t c u e i t l i d h i n c r g s A 0 8 8 0 s A g r c n i h d i l t i e u c B t s 0 9 a c i r e m A h t r o N S o u t h A m e r i c s t a c e t i h c r A 0 8 1 s 1 g n 5 i d B l i u ISBN 978-978-12585-2-6 7 8 9 7 8 1 Editorial Department of Global Architecture Practice Editorial Department of Global Architecture -

C:\Users\Gutschow\Documents\CMU Teaching\Postwar Modern

Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Class #5 DISCUSSION: WHAT IS POSTWAR MODERN? Discuss: Joedicke, J. “Introduction,” Architecture Since 1945 (1969) Goldhagen & Legault, “Introduction: Critical Themes of Postwar Modernism,” in Anxious Modernisms Goldhagen, “Coda: Reconceptualizing Modernism,” in Anxious Modernisms Ockman: “Introduction,” in Architecture Culture, 1943-1968 Differentiate: Prewar Modernism; Postwar Modernism; Postmodernism Critical Themes of Postwar Modernism: Anxiety, Popular Culutre, Consumer Culture, Everyday Life, Anti- Architecture, Democratic Freedom, Homo Ludens (play), Primitivism, Authenticity, Architecture’s History, Regionalism, Place, Skepticism & Infatuation with Technology. Postwar Modern Architects & Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureates 2010: SANAA, Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa of Japan. 2009: Peter Zumthor of Switzerland 2008: Jean Nouvel of France 2007: Richard Rogers of the United Kingdom 2006: Paulo Mendez da Rocha of Brazil 2005: Thom Mayne of the United States 2004: Zaha Hadid of the United Kingdom 2003: Jorn Utzon of Denmark 2002: Glenn Murcutt of Australia 2001: Herzog and de Meuron of Switzerland 2000: Rem Koolhaas of The Netherlands 1999: Norman Foster of the United Kingdom 1998: Renzo Piano of Italy 1997: Sverre Fehn of Norway 1996: Rafael Moneo of Spain presented 1995: Tadao Ando of Japan 1994: Christian de Portzamparc of France 1993: Fumihiko Maki of Japan 1992: Alvaro Siza of Portugal 1991: Robert Venturi of the United States 1990: Aldo Rossi of Italy 1989: Frank O. Gehry of the United States 1988: Gordon Bunshaft of the United States and Oscar Niemeyer of Brazil 1987: Kenzo Tange of Japan 1986: Gottfried Boehm of Germany 1985: Hans Hollein of Austria 1984: Richard Meier of the United States 1983: Ieoh Ming Pei of the United States 1982: Kevin Roche of the United States 1981: James Stirling of Great Britain 1980: Luis Barragan of Mexico 1979: Philip Johnson of the United States. -

Altelier Hans Hollein Principal Architect(S): Hollein, Hans

ALTELIER HANS HOLLEIN PRINCIPAL ARCHITECT(S): HOLLEIN, HANS LOCATION: VIENNA, AUSTRIA FIRM OPENED: 1964 EMPLOYEES: 1 FIRM PHILOSOPHY Known as a universal artist, Hollein’s design philosophies are derived from the idea that one must avoid narrow and easily defendable positions to achieve original and quality design. Hollein says that evolution of early design ideas should be re-examined and realized in future work. He believes that design is not a profession to be pigeon-holed, and encourages exploration of the aforementioned design elements in other ways than just architecture. HISTORY Hans Hollein studied architecture and urban planning at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago until 1959. In 1960 he finished his studies at the University of California in Berkeley as Master of Architecture. He established his own solo architectural studio in Vienna in 1964. He has since realized works in Austria, France, Germany, Iran, Italy, Spain, Russia, USA, Peru, and Japan. Hollein used to employ interns to help around the office. However, in 2010 he joined a partnership with ZT-GmbH, another architectural firm, leaving his solo studio to focus on his art and furniture design. His most notable awards include the following: the Pritzker Architecture Prize, 1985; the Reynolds Memorial Award, 1966 and 1984; the Prize of the City of Vienna for Architecture, 1974; the Grand Austrian State Awards, 1983; the Austrian Ehrenzeichen für Wissenschaft und Kunst, 1990; the Goldenes Ehrenzeichen für Verdienste um das Land Wien, 1994; the Grosse Verdienstkreuz des Verdienstordens der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1997; and the Arnold W. Brunner Memorial Prize of Architecture in New York, 2004.