Tarsila Do Amaral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feb. 7 to Apr. 30, 2017 Great Hall

Ministry of Culture and Museu de Arte To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Moderna de São Paulo present exhibition that inaugurated Brazilian modernism, Anita Malfatti: 100 Years of Modern Art gathers at FEB. 7 MAM’s Great Hall about seventy different works covering the path of one of the main names in TO Brazilian art in the 20th century. Anita Malfatti’s exhibition in 1917 was crucial to the emergence of the group who would champion modern art in Brazil, so much so that APR. 30, critic Paulo Mendes de Almeida considered her as the “most historically critical character in the 2017 1922 movement.” Regina Teixeira de Barros’ curatorial work reveals an artist who is sensitive to trends and discussions in the first half of the 20th century, mindful of her status and her choices. This exhibition at MAM recovers drawings and paintings by Malfatti, divided into three moments in her path: her initial years that consecrated her as “trigger of Brazilian modernism”; the time she spent training in Paris and her naturalist production; and, finally, her paintings with folk themes. With essays by Regina Teixeira de Barros and GREAT Ana Paula Simioni, this edition of Moderno MAM Extra is an invitation for the public to get to know HALL this great artist’s choices. Have a good read! MASTER SPONSORSHIP SPONSORSHIP CURATED BY REALIZATION REGINA TEIXEIRA DE BARROS One hundred years have gone by since the 3 03 ANITA Exposição de pintura moderna Anita Malfatti [Anita Malfatti Modern Painting Exhibition] would forever CON- MALFATTI, change the path of art history in Brazil. -

Tarsila Do Amaral, Anita Malfatti

MULHERES DE CONOTAÇÃO CULTURAL :TARSILA DO AMARAL, ANITA MALFATTI Autores: THAIS CARDOSO SANTOS, JANETE RODRIGUES PEREIRA, MARIA DE FÁTIMA GOMES LIMA DO NASCIMENTO, THAIS CARDOSO SANTOS Introdução A década de 1920 foi um período de mudanças estruturais, como o crescimento industrial impulsionado pelas exportações da Primeira guerra Mundial pelo próprio consumo interno; dentre essas mudanças se destacaram também as novas tendências artísticas culturais. Entre essas, podemos citar o modernismo, surrealismo, impressionismo e o cubismo. Tendo em vista que tais movimentos se despontaram na Europa, os mesmos obtiveram grande repercussão também no Brasil. No contexto da Republica Oligárquica e da chamada política do café com leite entre 11 e 17 de fevereiro de 1922, ocorreu um movimento artístico e intelectual denominado “Semana da Arte Moderna” que modificou sensivelmente a sociedade brasileira. Esse movimento de Arte Moderna ocorreu, portanto no Teatro Municipal de São Paulo, em 1922, e como objetivo principal mostrar as novas tendências artísticas aqui já citadas, que vigoravam na Europa. No Brasil, o descontentamento com o estilo anterior foi mais explorado no campo da literatura, com maior ênfase na poesia. Entre os escritores modernistas destacam-se: Oswald de Andrade, Guilherme de Almeida e Manuel Bandeira. Na pintura, destacou-se Anita Malfatti, Tarsila do Amaral, Di Cavalcante e Victor Brecheret. Dentro desse contexto histórico e político social, as mulheres ocuparam um papel de destaque na cultura. Espaço que reivindicavam desde o século XIX, quando passaram a desafiar a sociedade,ao comerciar, prestar serviços e trabalhar fora de casa nas indústrias. Desta forma, a Semana da Arte moderna, trouxe consigo uma maneira muito especial para as mulheres mostrar o quanto havia mudado e contribuído para a sociedade brasileira atingir o auge nas artes. -

70 Documentos Do Acervo

DOBRA DOBRA MUSEU LASAR SEGALL MUSEU LASAR SEGALL Os documentos reunidos em vida por Lasar Segall ( ) formam o Arquivo Lasar Segall, uma importante coleção para pesquisa da história da arte brasileira e europeia. Esse acervo, composto por cerca de . itens, constitui-se, pelo seu ineditismo, natureza e dimensão, em uma das mais importantes fontes para a análise e compreensão da vida e da obra do artista, um dos principais nomes da arte moderna brasileira. _CAPA final_70 documentos_MLS.indd 1 06/02/20 11:05 DOBRA DOBRA _CAPA final_70documentos_MLS.indd 2 DOBRA DOBRA DOBRA DOBRA 06/02/20 11:05 MeMória e História MUSEU LASAR SEGALL 70 DOCUMENTOS DO ACERVO LASAR SEGALL MUSEUM 70 DOCUMENTS FROM THE ARCHIVES _FINAL_miolo novo_70 documentos_sem codigo com inglês.indd 1 06/02/20 11:04 _FINAL_miolo novo_70 documentos_sem codigo com inglês.indd 2 06/02/20 11:04 MUSEU LASAR SEGALL 70 DOCUMENTOS DO ACERVO LASAR SEGALL MUSEUM 70 DOCUMENTS FROM THE ARCHIVES _FINAL_miolo novo_70 documentos_sem codigo com inglês.indd 3 06/02/20 11:04 _FINAL_miolo novo_70 documentos_sem codigo com inglês.indd 4 06/02/20 11:04 7 ApresentAção Daniel Rincon caiRes 11 MeMóriA e históriA VeRa D’HoRta 31 CurAdoriA e Arquivos de Museus de Arte ana MagalHães 49 divisAs biográficas 63 diásporAs, derivAs, desloCAMentos 79 inquietAções estéticas 99 revolução ModernistA nA AleMAnhA 133 ModernisMos brAsileiros 169 intiMidAde 177 rAízes JudAicas 189 AnotAções téCnicas 197 biblioteCA pArtiCulAr 209 eMpreendiMentos iMobiliários 221 english version 287 Créditos _FINAL_miolo novo_70 documentos_sem codigo com inglês.indd 5 06/02/20 11:04 _FINAL_miolo novo_70 documentos_sem codigo com inglês.indd 6 06/02/20 11:04 Apresentação Daniel Rincon caiRes Em 1986 o Arquivo Lasar Segall inaugurava a sua jorna- da. -

O Verde Na Metrópole: a Evolução Das Praças E Jardins Em Curitiba (1885-1916)

APARECIDA VAZ DA SILVA BAHLS O VERDE NA METRÓPOLE: A EVOLUÇÃO DAS PRAÇAS E JARDINS EM CURITIBA (1885-1916) Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre. Curso de Pós-Graduação em História, Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes, Universidade Federal do Paraná. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Maria Luiza Andreazza. Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Magnus Roberto de Mello Pereira CURITIBA 1998 AGRADECIMENTOS À Fundação Cultural de Curitiba, sem a qual este trabalho não poderia ter se concretizado, em especial à Professora Oksana Boruszenko, Diretora do Patrimônio Histórico-Cultural. Aos professores Etelvina Maria de Castro Trindade, Magnus Roberto de Mello Pereira e Maria Luiza Andreazza, pela orientação e apoio. Aos funcionários dos arquivos pesquisados: Arquivo Público do Paraná, Biblioteca Pública do Paraná, Casa da Memória e, especialmente, a Helena Soares, do Museu Paranaense. A meus pais, pelo incentivo, e aos parentes e amigos: Aarão, Adão, Afonso, André, Antony, Edward, Fernanda, Gabriel, Gisele, Isabel, Marcelo e Solange. Com amor, ao meu marido Allan, pela compreensão, apoio e auxílio nos momentos difíceis. SUMÁRIO INTRODUÇÃO 01 PARTE I - A CIDADE E O VERDE 09 1 O VERDE NO SURGIMENTO DO URBANISMO MODERNO 10 1.1 A FÁBRICA EA CIDADE 11 1.2 A CIDADE E SUAS TRANSFORMAÇÕES NA ERA INDUSTRIAL 14 1.3 MORAR NA CIDADE INDUSTRIAL 17 1.4 0 PODER PÚBLICO E OS PROBLEMAS URBANOS 21 1.5 AS NOVAS CONCEPÇÕES URBANÍSTICAS 30 1.60 VERDE NA METRÓPOLE 37 2 O VERDE E O DESENVOLVIMENTO DO URBANISMO NO BRASIL 49 2.1 AS TRANSFORMAÇÕES URBANAS NO BRASIL OITOCENTISTA... -

Group Exhibition at Pina Estação Brings Together Works Which Allude to Fictions About the Origin of the World

Group exhibition at Pina Estação brings together works which allude to fictions about the origin of the world Experimental works by Antonio Dias, Carmela Gross, Lothar Baumgarten, Solange Pessoa and Tunga suggest cosmogonic narratives Opening: November 10th, 2018, Saturday, at 11 am Visitation: until February 11th, 2019 Pinacoteca de São Paulo, museum of the São Paulo State Secretariat of Culture, presents, from November 10th, 2018 to February 11th, 2019, the exhibition Invention of Origin, on the fourth floor of Pina Estação. With curatorship by Pinacoteca's Nucleus of Research and Criticism and under general coordination of José Augusto Ribeiro, the museum curator, the group exhibition takes as the starting point the film The Origin of the Night: Amazon Cosmos (1973-77), by the German artist Lothar Baumgarten. The film, rarely exhibited, will be presented alongside a selection of works by four Brazilian artists — Antonio Dias, Carmela Gross, Solange Pessoa and Tunga. In common, the selected works allude to primordial times and actions which could have contributed to the narratives about the origin of life. Shot on 16 mm between 1973 and 1977, The Origin of the Night: Amazon Cosmos, by Lothar Baumgarten, is based on a Tupi myth, registered by the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, on the origin of the night — which, according to the narrative, used to “sleep” under waters, when animals still did not exist and things had the power of speech. From images captured in the Reno River, between Dusseldorf and Cologne, the artist creates ambiguous situations. “The images are paradoxical, they show a kind of virgin forest in which, however, the waste of human civilization is spread. -

Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil (São Paulo, 25-27 Apr 18)

Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil (São Paulo, 25-27 Apr 18) São Paulo, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Apr 25–27, 2018 Deadline: Mar 9, 2018 Erika Zerwes In 1937 the German government, led by Adolf Hitler, opened a large exhibition of modern art with about 650 works confiscated from the country's leading public museums entitled Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst). Marc Chagall, Otto Dix, Max Ernst, George Grosz, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Piet Mondrian and Lasar Segall were among the 112 artists who had works selected for the show. Conceived to be easily assimilated by the general public, the exhibition pre- sented a highly negative and biased interpretation of modern art. The Degenerate Art show had a rather large impact in Brazil. There have been persecutions to modern artists accused of degeneration, as well as expressions of support and commitment in the struggle against totalitarian regimes. An example of this second case was the exhibition Arte condenada pelo III Reich (Art condemned by the Third Reich), held at the Askanasy Gallery (Rio de Janeiro, 1945). The event sought to get support from the local public against Nazi-fascism and to make modern art stand as a synonym of freedom of expression. In the 80th anniversary of the Degenerate Art exhibition, the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Contemporary Art, in partnership with the Lasar Segall Museum, holds the International Seminar “Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil”. The objective is to reflect on the repercus- sions of the exhibition Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst) in Brazil and on the persecution of mod- ern art in the country in the first half of the 20th century. -

Littleton Bible Chapel Position Paper Covering and Uncovering of The

Littleton Bible Chapel Position Paper Covering and Uncovering of the Head during Prayer and Ministry of the Word 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 It has been the practice of LBC for the past forty-five years to ask women to cover their heads when they pray and teach publicly, and for men to uncover their heads when they pray and teach in a public setting. This practice is not an empty tradition of our church but a direct injunction of the Scriptures. We have prepared the following paper on 1 Corinthians 11:2-16, for you to consider the accuracy and the truthfulness of our practice. It is our desire to encourage believers to take this passage seriously and to consistently practice the teaching therein. This has been a long neglected passage, and today is completely unacceptable in our feminist environment. We understand the offense of this teaching. But since we take the passage at face value and not as cultural, we have no choice but to practice its teaching. Our desire as elders is to make people aware of what the Bible teaches about this distinctive Christian practice and to encourage both men and women to practice this teaching. If however, people disagree with our interpretation, we do not force this practice on anyone. We respect the liberty of the conscience of all our fellow believers. 1 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 Headship and Subordination Symbolized by Covering and Uncovering of the Head The letter of 1 Corinthians deals with many practical local church issues and problems, ones that affect all churches in all ages. -

* Kiki from Montparnasse for More Than Twenty Years, She Was the Muse of the Parisian Neighbourhood of Montparnasse. Alice Prin

Blog Our blog will be a place used to tell you in detail all those museum's daily aspects, its internal functioning, its secrets, anecdotes and curiosities widely unknown about the building and our collections. How does people work in the museum when it is closed? What secrets lay behind the exemplars of our library? What do the “inhabitants” of our collections hide?... On this space the MACA completely opens its doors to everyone who wants to know us deeper. Welcome to the MACA! • Kiki de Montparnasse (Kiki from Montparnasse) | MACA's celebrities • Miró y el objeto (Miró and the object) | Publications • Derivas de la geometría (Geometry drifts) | Publications • Los patios de canicas (Marbles patios) | MACA's secrets • La Montserrat | MACA's celebrities • Una pasión privada (A private passion) | Publications • Estudiante en prácticas (Apprentice) | MACA's secrets • Arquitectura y arte (Architecture and art) | Publications • Nuestro público (Our public) | MACA's secrets • Gustavo Torner | MACA's celebrities • René Magritte y la Publicidad (René Magritte and Advertising) |MACA's celebrities * Kiki from Montparnasse For more than twenty years, she was the muse of the Parisian neighbourhood of Montparnasse. Alice Prin, who was commonly and widely called Kiki, posed for the best painters of the inter-war Europe and socialized with the most relevant artists of that period. Alice Ernestine Prin, Kiki, was born on the 2nd of October 1901 within a humble family from Châtillon-sur-Seine, a small city of Borgoña. Kiki visited Paris for the first time when she was thirteen and when she was fourteen her family send her to work in the capital. -

Pagu: a Arte No Feminino Como Performance De Si

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Interdisciplinar em Performances Culturais, para obtenção do título de Mestra em Performances Culturais pela Universidade Federal de Goiás. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Sainy Coelho Borges Veloso. Co-orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Marcela Toledo França de Almeida. GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. i ii iii Dedico este trabalho a quem sabe que a pele é fina diante da abertura do peito, que o coração a toca. Por quem sabe que é impossível viver por certos caminhos sem lutar e não brigar pela vida. Para quem entende que a paz e perdão não tem nada de silencioso quando já se viveu algumas guerras. E por quem vive como se sentisse o seu desaparecimento a cada dia, pois as flores não perdem a sua cor, apenas vivem o suficiente para não desbotar. iv AGRADECIMENTOS Não agradecerei neste trabalho a nomes específicos que me atravessaram na minha caminhada enquanto o escrevia, mas sim as experiências que passei a viver nesse período de tempo em que pela primeira vez me permite viver sem ser apenas agredida. Pelos dias que passei a cuidar de mim mesma. Pela minha caminhada em análise que me permitiu entender subjetivamente o que eu buscava quando coloquei essa temática como pesquisa a ser realizada. -

Spanish Painting During Developmentism

Spanish Painting during Developmentism From 1960 on, Spanish art consolidated the ground it had gained over the previous decade, in which informal- ism had managed to make itself noticed on the international scene through official promotion and awards given to artists like Antonio Saura and Antoni Tàpies. At the same time, a more lyrical side emerged, which, along with other members of this generation of varied aesthetic options, would set Cuenca’s Museum of Spanish Abstract Art in motion. tinued with what was called “veta brava” Informalism, international recognition was achieved by artists like Antoni Tàpies (1923-2012), who abandoned surrealist figuration in favour of a material informal- ism, Eduardo Chillida (1924-2002), an example of informalist sculpture, and José Guerrero (1914-1991) Spain’s represent- ative of the New York School. Others such as Fernando Zóbel (1924-1984), Gustavo Torner (1925) and Gerardo Rueda (1926- 1996), went on the form part of the central core of what was called the Cuenca Group, representatives of an abstract form that became known as lyrical. These three art- ists shared a sense of aesthetic perfection In the late Fifties and throughout the Sixties, Spain opened up to what lay beyond Fran- and purity of surfaces, producing reflec- co’s regime, so as to modernise the Spanish economy according to the liberal capitalism tive painting, with a very controlled feeling model, resulting in what were known as the Development Plans. One result of the end of far from spontaneity, thereby producing Spain’s isolation was a prolific period for Spanish art, which came into contact with the something that could be called “fake in- international scene for the first time. -

Impressionist & Modern

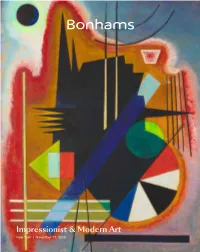

Impressionist & Modern Art New York | November 17, 2020 Impressionist & Modern Art New York | Tuesday November 17, 2020 at 5pm EST BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS COVID-19 SAFETY STANDARDS 580 Madison Avenue New York Register to bid online by visiting Bonhams’ galleries are currently New York, New York 10022 Molly Ott Ambler www.bonhams.com/26154 subject to government restrictions bonhams.com +1 (917) 206 1636 and arrangements may be subject Bonded pursuant to California [email protected] Alternatively, contact our Client to change. Civil Code Sec. 1812.600; Services department at: Bond No. 57BSBGL0808 Preeya Franklin [email protected] Preview: Lots will be made +1 (917) 206 1617 +1 (212) 644 9001 available for in-person viewing by appointment only. Please [email protected] SALE NUMBER: contact the specialist department IMPORTANT NOTICES 26154 Emily Wilson on impressionist.us@bonhams. Please note that all customers, Lots 1 - 48 +1 (917) 683 9699 com +1 917-206-1696 to arrange irrespective of any previous activity an appointment before visiting [email protected] with Bonhams, are required to have AUCTIONEER our galleries. proof of identity when submitting Ralph Taylor - 2063659-DCA Olivia Grabowsky In accordance with Covid-19 bids. Failure to do this may result in +1 (917) 717 2752 guidelines, it is mandatory that Bonhams & Butterfields your bid not being processed. you wear a face mask and Auctioneers Corp. [email protected] For absentee and telephone bids observe social distancing at all 2077070-DCA times. Additional lot information Los Angeles we require a completed Bidder Registration Form in advance of the and photographs are available Kathy Wong CATALOG: $35 sale. -

FLETCHER-THESIS.Pdf

Copyright by Kanitra Shenae Fletcher 2011 The Thesis Committee for Kanitra Shenae Fletcher Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Damage Control: Black Women's Visual Resistance in Brazil and Beyond APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Moyosore Okediji Cherise Smith Damage Control: Black Women's Visual Resistance in Brazil and Beyond by Kanitra Shenae Fletcher, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To my beloved late aunt Aundra Thornton. Abstract Damage Control: Black Women's Visual Resistance in Brazil and Beyond Kanitra Shenae Fletcher, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Moyosore Okediji Jezebels, Mammies, and Matriarchs… These labels signify racialized and gendered social constructions that transnationally pervade the lives of black women. By contextualizing black women’s artwork as visual responses to social subjugation and objectification, one can discern the (literal) materialization of black feminist epistemology through artistic production and the aesthetic concerns that drive expressive work. This thesis therefore analyzes black Brazilian artist Rosana Paulino’s work as a visual form of resistance to three major “controlling images” of black women in Brazil as sexually promiscuous, domestic laborers, and unfit mothers. Her work represents not only the Brazilian black woman’s experience; it broadens and deepens the conversation on black women’s art in Africa and its diasporas, where similar stereotypes exist. Several v of Paulino’s personal statements and artworks address subjects that parallel those made by black women artists--María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Lorna Simpson, Zanele Muholi, and Wangechi Mutu, to name a few--whose artwork is also considered in this paper.