Women's Health Pocket Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaginitis and Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding

UCSF Family Medicine Board Review 2013 Vaginitis and Abnormal • There are no relevant financial relationships with any commercial Vaginal Bleeding interests to disclose Michael Policar, MD, MPH Professor of Ob, Gyn, and Repro Sciences UCSF School of Medicine [email protected] Vulvovaginal Symptoms: CDC 2010: Trichomoniasis Differential Diagnosis Screening and Testing Category Condition • Screening indications – Infections Vaginal trichomoniasis (VT) HIV positive women: annually – Bacterial vaginosis (BV) Consider if “at risk”: new/multiple sex partners, history of STI, inconsistent condom use, sex work, IDU Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) • Newer assays Skin Conditions Fungal vulvitis (candida, tinea) – Rapid antigen test: sensitivity, specificity vs. wet mount Contact dermatitis (irritant, allergic) – Aptima TMA T. vaginalis Analyte Specific Reagent (ASR) Vulvar dermatoses (LS, LP, LSC) • Other testing situations – Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) Suspect trich but NaCl slide neg culture or newer assays – Psychogenic Physiologic, psychogenic Pap with trich confirm if low risk • Consider retesting 3 months after treatment Trichomoniasis: Laboratory Tests CDC 2010: Vaginal Trichomoniasis Treatment Test Sensitivity Specificity Cost Comment Aptima TMA +4 (98%) +3 (98%) $$$ NAAT (like GC/Ct) • Recommended regimen Culture +3 (83%) +4 (100%) $$$ Not in most labs – Metronidazole 2 grams PO single dose Point of care – Tinidazole 2 grams PO single dose •Affirm VP III +3 +4 $$$ DNA probe • Alternative regimen (preferred for HIV infected -

Velvi Product Information Brochure

Vaginal Dilatator www.velvi-vaginismus.com The Velvi Kit is a set of six vaginal dilators, a removable handle and an instructions for use manual. Each Velvi dilator is a purple cylindrical element, smoothly shaped in plastic and specifically adapted to vaginal dilation exercises. Velvi Kit - 6 graduated vaginal dilators Self treatment for painful sexual intercourse : Vaginismus Vulvodynia and dyspareunia Vaginal stenosis vaginal agenesis (MRKH syndrome) After gynecological surgery or trauma following childbirth. Velvi dilators dimensions: Size 1: 4 cm in length with a base diameter of 1 cm. Size 2: 5.5 cm in length with a base diameter of 1.5 cm. Size 3: 7 cm in length with a base diameter of 2 cm. Size 4: 8.5 cm in length with a base diameter of 2.5 cm. Size 5: 10 cm in length with a base diameter of 3 cm. Size 6: 11.5 cm in length with a base diameter of 3.5 cm. The handle can be locked on each dilator Velvi With a simple rotating movement. How to use properly a Velvi dilator ? First, generously lubricate the dilator and the entrance to your vagina. Then gently spread your labia and insert the dilator very slowly inside your vaginal canal. Keep in mind that pushing on your perineum will help you while introducing it. Do not try to guide the dilator, in general it will keep going in the right direction by itself. When starting a new exercise with a dilator, do not immediately try to make any sort of movements. Wait a bit and let some time to your vagina to get used to the fact that a dilator is inserted without moving. -

Self-Care Practices and Immediate Side Effects in Women with Gynecological Cancer

Rev. Enferm. UFSM - REUFSM Santa Maria, RS, v. 11, e35, p. 1-21, 2021 DOI: 10.5902/2179769248119 ISSN 2179 -7692 Artigo Original Submiss ão : 07 /21 /20 20 Aprovação: 03 /18 /202 1 Publicação: 04 /20 /202 1 SelfSelf----carecare practices and immediate side effects in women with gynecological cancer in brachytherapy* Práticas de autocuidado e os efeitos colaterais imediatos em mulheres com câncer ginecológico em braquiterapia Prácticas de autocuidado y los efectos colaterales inmediatos en mujeres con cáncer ginecológico en braquiterapia Rosimeri Helena da Silva III, Luciana Martins da Rosa IIIIII , Mirella Dias IIIIIIIII , Nádia Chiodelli Salum IVIVIV , Ana Inêz Severo Varela VVV, Vera Radünz VIVIVI Abstract : ObjectiveObjective: to reveal the immediate side effects and self-care practices adopted by women with gynecological cancer submitted to brachytherapy. MethodMethod:Method narrative research, conducted with 12 women, in southern Brazil, between December/2018 and January/2019, including semi-structured interviews submitted to content analysis. ResultsResults: three thematic categories emerged from the analysis: Care oriented and adopted by women in pelvic brachytherapy; Immediate side effects perceived by women in pelvic brachytherapy; Care not guided by health professionals. The care provided by the nurses most reported by the women was vaginal dilation, use of a shower and vaginal lubricant, tea consumption, cleaning, and storage of the vaginal dilator. The side effects most frequently mentioned in the interviews were urinary and intestinal changes in the skin and mucous membranes. ConclusionConclusion: nursing care in brachytherapy must prioritize care to prevent and control genitourinary and cutaneous changes, including self-care practices. I Professional Master in Nursing Care Management, Nurse at the Oncological Research Center, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil. -

Dyspareunia Treated by Bilateral Pudendal Nerve Block Gregory Amend, Yimei Miao, Felix Cheung, John Fitzgerald, Brian Durkin, S

www.symbiosisonline.org Symbiosis www.symbiosisonlinepublishing.com Case Report SOJ Anesthesiology and Pain Management Open Access Dyspareunia Treated By Bilateral Pudendal Nerve Block Gregory Amend, Yimei Miao, Felix Cheung, John Fitzgerald, Brian Durkin, S. Ali Khan and Srinivas Pentyala* Departments of Urology and Anesthesiology, Stony Brook Medical Center, USA Received: November 19, 2013; Accepted: March 13, 2014, Published: March 14, 2014 *Corresponding author: Srinivas Pentyala, Department of Anesthesiology, Stony Brook Medical Center, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8480, New York, USA; Tel: 631-444-2974; Fax: 631-444-2907; E-mail: [email protected] patient’s last sexual attempt was 2 weeks prior to presentation. Abstract The patient was in a stable long term marriage with no history of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. Patient denied use of alcohol, dyspareunia of unclear etiology, who was successfully managed with tobacco, and illicit drugs. There was no history of psychiatric In this report, we present a patient with refractory superficial a bilateral pudendal nerve block. Initial workup failed to identify conditions, endocrine abnormalities, neurologic illnesses, pelvic trauma, sexually transmitted infections, incontinence, pudendalan obvious nerve source block for alleviated the pain the and problem first-line to threetherapy years for follow- post- up.menopausal In this report, superficial we review dyspareunia the current was dyspareunia not effective. literature A bilateral and vaginal stenosis. The patient previously had multiple abdominal propose a diagnostic algorithm. incisions,pelvic floor including disorders, two electiveurological C-sections problems, and endometriosis, a total abdominal or Keywords: Dyspareunia; Organ prolapse; Vaginitis; Pudendal nerve hysterectomy for dysfunctional uterine bleeding 4 years prior block; Vulvar vestibulitis to presentation. -

New Insights Into Human Female Reproductive Tract Development

UCSF UC San Francisco Previously Published Works Title New insights into human female reproductive tract development. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7pm5800b Journal Differentiation; research in biological diversity, 97 ISSN 0301-4681 Authors Robboy, Stanley J Kurita, Takeshi Baskin, Laurence et al. Publication Date 2017-09-01 DOI 10.1016/j.diff.2017.08.002 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Differentiation 97 (2017) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Differentiation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/diff New insights into human female reproductive tract development MARK ⁎ Stanley J. Robboya, , Takeshi Kuritab, Laurence Baskinc, Gerald R. Cunhac a Department of Pathology, Duke University, Davison Building, Box 3712, Durham, NC 27710, United States b Department of Cancer Biology and Genetics, The Comprehensive Cancer Center, Ohio State University, 460 W. 12th Avenue, 812 Biomedical Research Tower, Columbus, OH 43210, United States c Department of Urology, University of California, 400 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94143, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: We present a detailed review of the embryonic and fetal development of the human female reproductive tract Human Müllerian duct utilizing specimens from the 5th through the 22nd gestational week. Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) as well as Urogenital sinus immunohistochemical stains were used to study the development of the human uterine tube, endometrium, Uterovaginal canal myometrium, uterine cervix and vagina. Our study revisits and updates the classical reports of Koff (1933) and Uterus Bulmer (1957) and presents new data on development of human vaginal epithelium. Koff proposed that the Cervix upper 4/5ths of the vagina is derived from Müllerian epithelium and the lower 1/5th derived from urogenital Vagina sinus epithelium, while Bulmer proposed that vaginal epithelium derives solely from urogenital sinus epithelium. -

A Review on the Outcome of Patient Managed in One Stop Postmenopausal Bleeding Clinic in New Territories East Cluster, NTEC

A Review on the Outcome of Patient managed in One Stop Postmenopausal Bleeding Clinic in New Territories East Cluster, NTEC Principal Investigator: Dr. CHEUNG Chun Wai Co-investigators: Dr. FUNG Wen Ying, Linda Dr. CHAN Wai Yin, Winnie Prof. Lao Tzu Hsi, Terence Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong. Version: 1 Date: 24 Jul 2017 1 Introduction: Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is a common gynaecological complaint, accounting for up to 5 to 10 % of postmenopausal women being referred to gynaecological outpatient clinic (1, 2). It also comprised of up to 10% of our outpatient gynaecological referral. In general, 60 % of women with postmenopausal bleeding have no organic causes identified, whilst benign causes of PMB includes atrophic vaginitis, endometrial polyp, submucosal fibroid and functional endometrium. However, between 5.7 to 11.5% of women with postmenopausal bleeding have endometrial carcinoma (3, 4, 5), which is the fourth most common cancer among women (6), therefore, it is important to investigate carefully to exclude genital tract cancer. In the past, often women with PMB require multiple clinic visits in order to reach a final diagnosis. This not only increase the medical cost as a whole, but also imposes an enormous stress and burden on patients, concerning about delayed or overlooked diagnosis of genital tract cancer. A One-stop postmenopausal bleeding clinic has been established since February, 2002 by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, New Territories East cluster (NTEC) aiming at providing immediate assessment of women with postmenopausal bleeding in one single outpatient clinic assessment. -

Once in a Lifetime Procedures Code List 2019 Effective: 11/14/2010

Policy Name: Once in a Lifetime Procedures Once in a Lifetime Procedures Code List 2019 Effective: 11/14/2010 Family Rhinectomy Code Description 30160 Rhinectomy; total Family Laryngectomy Code Description 31360 Laryngectomy; total, without radical neck dissection 31365 Laryngectomy; total, with radical neck dissection Family Pneumonectomy Code Description 32440 Removal of lung, pneumonectomy; Removal of lung, pneumonectomy; with resection of segment of trachea followed by 32442 broncho-tracheal anastomosis (sleeve pneumonectomy) 32445 Removal of lung, pneumonectomy; extrapleural Family Splenectomy Code Description 38100 Splenectomy; total (separate procedure) Splenectomy; total, en bloc for extensive disease, in conjunction with other procedure (List 38102 in addition to code for primary procedure) Family Glossectomy Code Description Glossectomy; complete or total, with or without tracheostomy, without radical neck 41140 dissection Glossectomy; complete or total, with or without tracheostomy, with unilateral radical neck 41145 dissection Family Uvulectomy Code Description 42140 Uvulectomy, excision of uvula Family Gastrectomy Code Description 43620 Gastrectomy, total; with esophagoenterostomy 43621 Gastrectomy, total; with Roux-en-Y reconstruction 43622 Gastrectomy, total; with formation of intestinal pouch, any type Family Colectomy Code Description 44150 Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with ileostomy or ileoproctostomy 44151 Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with continent ileostomy 44155 Colectomy, -

Uterine Anomalies in Infertility - an Evaluation by Diagnostic Hysterolaparoscopy

Jebmh.com Original Research Article Uterine Anomalies in Infertility - An Evaluation by Diagnostic Hysterolaparoscopy Benudhar Pande1, Soumyashree Padhan2, Pranati Pradhan3 1, 2, 3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Veer Surendra Sai Institute of Medical Science and Research, Burla, Odisha, India. ABSTRACT BACKGROUND About 10 - 15 % of reproductive age couples are affected by infertility.1 According Corresponding Author: Dr. Pranati Pradhan, to WHO 60 - 80 million couples currently suffer from infertility.2 Prevalence of Assistant Professor, infertility is rapidly increasing globally.3 Uterine factors of infertility include uterine Department of O & G, anomalies, fibroid uterus, synechiae, Asherman’s syndrome, and failure of VIMSAR, Burla – 768017, implantation without any known primary causes. Congenital uterine malformations Odisha, India. are seen in 10 % cases of infertile women. We wanted to evaluate the anomalies E-mail: [email protected] of uterus in case of primary and secondary infertility by DHL (diagnostic hysterolaperoscopy). DOI: 10.18410/jebmh/2020/580 METHODS How to Cite This Article: Pande B, Padhan S, Pradhan P. Uterine This is a hospital-based, observational study, conducted in the Department of anomalies in infertility-an evaluation by Obstetrics and Gynaecology, VIMSAR, Burla, from November 2017 to October diagnostic hysterolaparoscopy. J Evid 2019. Diagnostic hysterolaparoscopy was done in 100 infertility cases. Based Med Healthc 2020; 7(48), 2831- 2835. DOI: 10.18410/jebmh/2020/580 RESULTS In our study, uterine anomaly i.e. septate uterus was the most common Submission 03-09-2020, hysteroscopic abnormaly found in 23 cases followed by submucous fibroid, polyp, Peer Review 10-09-2020, Acceptance 17-10-2020, synechiae and bicornuate uterus. -

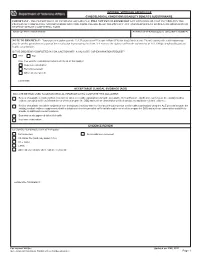

Gynecological-DBQ

INTERNAL VETERANS AFFAIRS USE GYNECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS DISABILITY BENEFITS QUESTIONNAIRE IMPORTANT - THE DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS (VA) WILL NOT PAY OR REIMBURSE ANY EXPENSES OR COST INCURRED IN THE PROCESS OF COMPLETING AND/OR SUBMITTING THIS FORM. PLEASE READ THE PRIVACY ACT AND RESPONDENT BURDEN INFORMATION ON REVERSE BEFORE COMPLETING FORM. NAME OF PATIENT/VETERAN PATIENT/VETERAN'S SOCIAL SECURITY NUMBER NOTE TO PHYSICIAN - Your patient is applying to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for disability benefits. VA will consider the information you provide on this questionnaire as part of their evaluation in processing the claim. VA reserves the right to confirm the authenticity of ALL DBQs completed by private health care providers. IS THIS DBQ BEING COMPLETED IN CONJUNCTION WITH A VA21-2507, C&P EXAMINATION REQUEST? YES NO If no, how was the examination completed (check all that apply)? In-person examination Records reviewed Other, please specify: Comments: ACCEPTABLE CLINICAL EVIDENCE (ACE) INDICATE METHOD USED TO OBTAIN MEDICAL INFORMATION TO COMPLETE THIS DOCUMENT: Review of available records (without in-person or video telehealth examination) using the Acceptable Clinical Evidence (ACE) process because the existing medical evidence provided sufficient information on which to prepare the DBQ and such an examination will likely provide no additional relevant evidence. Review of available records in conjunction with a telephone interview with the Veteran (without in-person or telehealth examination) using the ACE process because the existing medical evidence supplemented with a telephone interview provided sufficient information on which to prepare the DBQ and such an examination would likely provide no additional relevant evidence. -

Cervical Ectropion May Be a Cause of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis. Leia Mitchell

Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University Health Sciences Research Commons Obstetrics and Gynecology Faculty Publications Obstetrics and Gynecology 4-28-2017 Cervical Ectropion May Be a Cause of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis. Leia Mitchell Michelle King Heather Brillhart George Washington University Andrew Goldstein Follow this and additional works at: https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/smhs_obgyn_facpubs Part of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons APA Citation Mitchell, L., King, M., Brillhart, H., & Goldstein, A. (2017). Cervical Ectropion May Be a Cause of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis.. Sexual Medicine, (). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2017.03.001 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Obstetrics and Gynecology at Health Sciences Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Obstetrics and Gynecology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Health Sciences Research Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cervical Ectropion May Be a Cause of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis Leia Mitchell, MSc,1 Michelle King, MSc,1,2 Heather Brillhart, MD,3 and Andrew Goldstein, MD1,3 ABSTRACT Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is a poorly understood chronic vaginitis with an unknown etiology. Symptoms of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis include copious yellowish discharge, vulvovaginal discomfort, and dyspareunia. Cervical ectropion, the presence of glandular columnar cells on the ectocervix, has not been reported as a cause of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Although cervical ectropion can be a normal clinical finding, it has been reported to cause leukorrhea, metrorrhagia, dyspareunia, and vulvovaginal irritation. Patients with cervical ectropion and des- quamative inflammatory vaginitis are frequently misdiagnosed with candidiasis or bacterial vaginosis and repeatedly treated without resolution of symptoms. -

Overview of Surgical Techniques in Gender-Affirming Genital Surgery

208 Review Article Overview of surgical techniques in gender-affirming genital surgery Mang L. Chen1, Polina Reyblat2, Melissa M. Poh2, Amanda C. Chi2 1GU Recon, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 2Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Los Angeles, CA, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: ML Chen, AC Chi; (II) Administrative support: None; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: None; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: None; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Amanda C. Chi. 6041 Cadillac Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90034, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Gender related genitourinary surgeries are vitally important in the management of gender dysphoria. Vaginoplasty, metoidioplasty, phalloplasty and their associated surgeries help patients achieve their main goal of aligning their body and mind. These surgeries warrant careful adherence to reconstructive surgical principles as many patients can require corrective surgeries from complications that arise. Peri- operative assessment, the surgical techniques employed for vaginoplasty, phalloplasty, metoidioplasty, and their associated procedures are described. The general reconstructive principles for managing complications including urethroplasty to correct urethral bulging, vaginl stenosis, clitoroplasty and labiaplasty after primary vaginoplasty, and urethroplasty for strictures and fistulas, neophallus and neoscrotal reconstruction after phalloplasty are outlined as well. Keywords: Transgender; vaginoplasty; phalloplasty; metoidioplasty Submitted May 30, 2019. Accepted for publication Jun 20, 2019. doi: 10.21037/tau.2019.06.19 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tau.2019.06.19 Introduction the rectum and the lower urinary tract, formation of perineogenital complex for patients who desire a functional The rise in social awareness of gender dysphoria has led vaginal canal, labiaplasty, and clitoroplasty. -

Cervical Cancer

Cervical Cancer Ritu Salani, M.D., M.B.A. Assistant Professor, Dept. of Obstetrics & Gynecology Division of Gynecologic Oncology The Ohio State University Estimated gynecologic cancer cases United States 2010 Jemal, A. et al. CA Cancer J Clin 2010; 60:277-300 1 Estimated gynecologic cancer deaths United States 2010 Jemal, A. et al. CA Cancer J Clin 2010; 60:277-300 Decreasing Trends of Cervical Cancer Incidence in the U.S. • With the advent of the Pap smear, the incidence of cervical cancer has dramatically declined. • The curve has been stable for the past decade because we are not reaching the unscreened population. Reprinted by permission of the American Cancer Society, Inc. 2 Cancer incidence worldwide GLOBOCAN 2008 Cervical Cancer New cases Deaths United States 12,200 4,210 Developing nations 530,000 275,000 • 85% of cases occur in developing nations ¹Jemal, CA Cancer J Clin 2010 GLOBOCAN 2008 3 Cervical Cancer • Histology – Squamous cell carcinoma (80%) – Adenocarcinoma (15%) – Adenosquamous carcinoma (3 to 5%) – Neuroendocrine or small cell carcinoma (rare) Human Papillomavirus (HPV) • Etiologic agent of cervical cancer • HPV DNA sequences detected is more than 99% of invasive cervical carcinomas • High risk types: 16, 18, 45, and 56 • Intermediate types: 31, 33, 35, 39, 51, 52, 55, 58, 59, 66, 68 HPV 16 accounts for ~80% of cases HPV 18 accounts for 25% of cases Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. J Pathol 1999;189(1):12-9. 4 Viral persistence and Precancerous progression Normal lesion cervix Regression/ clearance Invasive cancer Risk factors • Early age of sexual activity • Cigggarette smoking • Infection by other microbial agents • Immunosuppression – Transplant medications – HIV infection • Oral contraceptive use • Dietary factors – Deficiencies in vitamin A and beta carotene 5 Multi-Stage Cervical Carcinogenesis Rosenthal AN, Ryan A, Al-Jehani RM, et al.