A Generalized Approach to Formal Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Structure of Index Sets and Reduced Indexed Grammars Informatique Théorique Et Applications, Tome 24, No 1 (1990), P

INFORMATIQUE THÉORIQUE ET APPLICATIONS R. PARCHMANN J. DUSKE The structure of index sets and reduced indexed grammars Informatique théorique et applications, tome 24, no 1 (1990), p. 89-104 <http://www.numdam.org/item?id=ITA_1990__24_1_89_0> © AFCET, 1990, tous droits réservés. L’accès aux archives de la revue « Informatique théorique et applications » im- plique l’accord avec les conditions générales d’utilisation (http://www.numdam. org/conditions). Toute utilisation commerciale ou impression systématique est constitutive d’une infraction pénale. Toute copie ou impression de ce fichier doit contenir la présente mention de copyright. Article numérisé dans le cadre du programme Numérisation de documents anciens mathématiques http://www.numdam.org/ Informatique théorique et Applications/Theoretical Informaties and Applications (vol. 24, n° 1, 1990, p. 89 à 104) THE STRUCTURE OF INDEX SETS AND REDUCED INDEXED GRAMMARS (*) by R. PARCHMANN (*) and J. DUSKE (*) Communicated by J. BERSTEL Abstract. - The set of index words attached to a variable in dérivations of indexed grammars is investigated. Using the regularity of these sets it is possible to transform an mdexed grammar in a reducedfrom and to describe the structure ofleft sentential forms of an indexed grammar. Résumé. - On étudie Vensemble des mots d'index d'une variable dans les dérivations d'une grammaire d'index. La rationalité de ces ensembles peut être utilisée pour transformer une gram- maire d'index en forme réduite, et pour décrire la structure des mots apparaissant dans les dérivations gauches d'une grammaire d'index. 1. INTRODUCTION In this paper we will further investigate indexed grammars and languages introduced by Aho [1] as an extension of context-free grammars and lan- guages. -

Genome Grammars

Genome Grammars Genome Sequences and Formal Languages Andreas de Vries Version: June 17, 2011 Wir sind aus Staub und Fantasie Andreas Bourani, Nur in meinem Kopf (2011) Contents 1 Genetics 5 1.1 Cell physiology ............................. 5 1.2 Amino acids and proteins ....................... 6 1.2.1 Geometry of peptide bonds .................. 8 1.2.2 Protein structure ......................... 10 1.3 Nucleic acids ............................... 12 1.4 DNA replication ............................. 14 1.5 Flow of information for cell growth .................. 16 1.5.1 The genetic code ......................... 18 1.5.2 Open reading frames, coding regions, and genes ...... 19 2 Formal languages 23 2.1 The Chomsky hierarchy ......................... 25 2.2 Regular languages ............................ 28 2.2.1 Regular expressions ....................... 30 2.3 Context-free languages ......................... 31 2.3.1 Linear languages ........................ 33 2.4 Context-sensitive languages ...................... 34 2.4.1 Indexed languages ....................... 35 2.5 Languages and machines ........................ 38 3 Grammar of DNA Strings 42 3.1 Searl’s approach to DNA language .................. 42 3.2 Gene regulation and inadequacy of context-free grammars ..... 45 3.3 DNA splicing rule ............................ 46 A Mathematical Foundations 49 A.1 Notation ................................. 49 A.2 Sets .................................... 49 A.3 Maps ................................... 52 A.4 Algebra ................................. -

What Was Wrong with the Chomsky Hierarchy?

What Was Wrong with the Chomsky Hierarchy? Makoto Kanazawa Hosei University Chomsky Hierarchy of Formal Languages recursively enumerable context- sensitive context- free regular Enduring impact of Chomsky’s work on theoretical computer science. 15 pages devoted to the Chomsky hierarchy. Hopcroft and Ullman 1979 No mention of the Chomsky hierarchy. 450 INDEX The same with the latest edition of Carmichael, R. D., 444 CNF-formula, 302 Cartesian product, 6, 46 Co-Turing-recognizableHopcroft, language, 209 Motwani, and Ullman (2006). CD-ROM, 349 Cobham, Alan, 444 Certificate, 293 Coefficient, 183 CFG, see Context-free grammar Coin-flip step, 396 CFL, see Context-free language Complement operation, 4 Chaitin, Gregory J., 264 Completed rule, 140 Chandra, Ashok, 444 Complexity class Characteristic sequence, 206 ASPACE(f(n)),410 Checkers, game of, 348 ATIME(t(n)),410 Chernoff bound, 398 BPP,397 Chess, game of, 348 coNL,354 Chinese remainder theorem, 401 coNP,297 Chomsky normal form, 108–111, 158, EXPSPACE,368 198, 291 EXPTIME,336 Chomsky, Noam, 444 IP,417 Church, Alonzo, 3, 183, 255 L,349 Church–Turing thesis, 183–184, 281 NC,430 CIRCUIT-SAT,386 NL,349 Circuit-satisfiability problem, 386 NP,292–298 CIRCUIT-VALUE,432 NPSPACE,336 Circular definition, 65 NSPACE(f(n)),332 Clause, 302 NTIME(f(n)),295 Clique, 28, 296 P,284–291,297–298 CLIQUE,296 PH,414 Sipser 2013Closed under, 45 PSPACE,336 Closure under complementation RP,403 context-free languages, non-, 154 SPACE(f(n)),332 deterministic context-free TIME(f(n)),279 languages, 133 ZPP,439 P,322 Complexity -

Mildly Context-Sensitive Grammar-Formalisms

Mildly Context Sensitive Grammar Formalisms Petra Schmidt Pfarrer-Lauer-Strasse 23 66386 St. Ingbert [email protected] Overview ,QWURGXFWLRQ«««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««« 3 Tree-Adjoining-Grammars 7$*V «««««««««««««««««««««««««« 4 CoPELQDWRU\&DWHJRULDO*UDPPDU &&*V ««««««««««««««««««««««« 7 /LQHDU,QGH[HG*UDPPDU /,*V ««««««««««««««««««««««««««« 8 3URRIRIHTXLYDOHQFH«««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««« 9 CCG ĺ /,*«««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««« 9 LIG ĺ 7$*«««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««« 10 TAG ĺ &&*«««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««« 13 Linear Context-)UHH5HZULWLQJ6\VWHPV /&)56V «««««««««««««««««««« 15 Multiple Context-Free-*UDPPDUV««««««««««««««««««««««««««« 16 &RQFOXVLRQ«««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««« 17 References««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««« 18 Introduction Natural languages are not context free. An example non-context-free phenomenon are cross-serial dependencies in Dutch, an example of which we show in Fig. 1. ik haar hem de nijlpaarden zag helpen voeren Fig. 1.: cross-serial dependencies A concept motivated by the intention of characterizing a class of formal grammars, which allow the description of natural languages such as Dutch with its cross-serial dependencies was introduced in 1985 by Aravind Joshi. This class of formal grammars is known as the class of mildly context-sensitive grammar-formalisms. According to Joshi (1985, p.225), a mildly context-sensitive language L has to fulfill three criteria to be understood as a rough characterization. These are: The parsing problem for L is solvable in -

![Cs.FL] 7 Dec 2020 4 a Model Programming Language and Its Grammar 11 4.1 Alphabet](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1877/cs-fl-7-dec-2020-4-a-model-programming-language-and-its-grammar-11-4-1-alphabet-1741877.webp)

Cs.FL] 7 Dec 2020 4 a Model Programming Language and Its Grammar 11 4.1 Alphabet

Describing the syntax of programming languages using conjunctive and Boolean grammars∗ Alexander Okhotin† December 8, 2020 Abstract A classical result by Floyd (\On the non-existence of a phrase structure grammar for ALGOL 60", 1962) states that the complete syntax of any sensible programming language cannot be described by the ordinary kind of formal grammars (Chomsky's \context-free"). This paper uses grammars extended with conjunction and negation operators, known as con- junctive grammars and Boolean grammars, to describe the set of well-formed programs in a simple typeless procedural programming language. A complete Boolean grammar, which defines such concepts as declaration of variables and functions before their use, is constructed and explained. Using the Generalized LR parsing algorithm for Boolean grammars, a pro- gram can then be parsed in time O(n4) in its length, while another known algorithm allows subcubic-time parsing. Next, it is shown how to transform this grammar to an unambiguous conjunctive grammar, with square-time parsing. This becomes apparently the first specifica- tion of the syntax of a programming language entirely by a computationally feasible formal grammar. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Conjunctive and Boolean grammars 5 2.1 Conjunctive grammars . .5 2.2 Boolean grammars . .6 2.3 Ambiguity . .7 3 Language specification with conjunctive and Boolean grammars 8 arXiv:2012.03538v1 [cs.FL] 7 Dec 2020 4 A model programming language and its grammar 11 4.1 Alphabet . 11 4.2 Lexical conventions . 12 4.3 Identifier matching . 13 4.4 Expressions . 14 4.5 Statements . 15 4.6 Function declarations . 16 4.7 Declaration of variables before use . -

From Indexed Grammars to Generating Functions∗

RAIRO-Theor. Inf. Appl. 47 (2013) 325–350 Available online at: DOI: 10.1051/ita/2013041 www.rairo-ita.org FROM INDEXED GRAMMARS TO GENERATING FUNCTIONS ∗ Jared Adams1, Eric Freden1 and Marni Mishna2 Abstract. We extend the DSV method of computing the growth series of an unambiguous context-free language to the larger class of indexed languages. We illustrate the technique with numerous examples. Mathematics Subject Classification. 68Q70, 68R15. 1. Introduction 1.1. Indexed grammars Indexed grammars were introduced in the thesis of Aho in the late 1960s to model a natural subclass of context-sensitive languages, more expressive than context-free grammars with interesting closure properties [1,16]. The original ref- erence for basic results on indexed grammars is [1]. The complete definition of these grammars is equivalent to the following reduced form. Definition 1.1. A reduced indexed grammar is a 5-tuple (N , T , I, P, S), such that 1. N , T and I are three mutually disjoint finite sets of symbols: the set N of non-terminals (also called variables), T is the set of terminals and I is the set of indices (also called flags); 2. S ∈N is the start symbol; 3. P is a finite set of productions, each having the form of one of the following: (a) A → α Keywords and phrases. Indexed grammars, generating functions, functional equations, DSV method. ∗ The third author gratefully acknowledges the support of NSERC Discovery Grant funding (Canada), and LaBRI (Bordeaux) for hosting during the completion of the work. 1 Department of Mathematics, Southern Utah University, Cedar City, 84720, UT, USA. -

Infinite Words As Determined by Languages of Their Prefixes

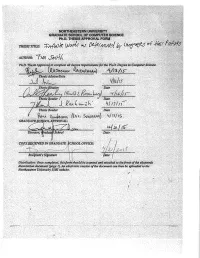

INFINITEWORDSASDETERMINEDBY LANGUAGESOFTHEIRPREFIXES tim smith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in computer science College of Computer and Information Science Northeastern University Boston, MA, USA April 2015 ABSTRACT We explore a notion of complexity for infinite words relating them to languages of their prefixes. An infinite language L determines an infinite word α if every string in L is a prefix of α. If L is regular, it is known that α must be ultimately periodic; conversely, every ul- timately periodic word is determined by some regular language. In this dissertation, we investigate other classes of languages and infi- nite words to see what connections can be made among them within this framework. We make particular use of pumping lemmas as a tool for studying these classes and their relationship to infinite words. • First, we investigate infinite words determined by various types of automata. We consider finite automata, pushdown automata, a generalization of pushdown automata called stack automata, and multihead finite automata, and relate these classes to ultimately periodic words and to a class of infinite words which we call mul- tilinear. • Second, we investigate infinite words determined by the parallel rewriting systems known as L systems. We show that certain infi- nite L systems necessarily have infinite subsets in other L systems, and use these relationships to categorize the infinite words deter- mined by a hierarchy of these systems, showing that it collapses to just three distinct classes of infinite words. • Third, we investigate infinite words determined by indexed gram- mars, a generalization of context-free grammars in which nonter- minals are augmented with stacks which can be pushed, popped, and copied to other nonterminals at the derivation proceeds. -

Indexed Counter Languages Informatique Théorique Et Applications, Tome 26, No 1 (1992), P

INFORMATIQUE THÉORIQUE ET APPLICATIONS J. DUSKE M. MIDDENDORF R. PARCHMANN Indexed counter languages Informatique théorique et applications, tome 26, no 1 (1992), p. 93-113 <http://www.numdam.org/item?id=ITA_1992__26_1_93_0> © AFCET, 1992, tous droits réservés. L’accès aux archives de la revue « Informatique théorique et applications » im- plique l’accord avec les conditions générales d’utilisation (http://www.numdam. org/conditions). Toute utilisation commerciale ou impression systématique est constitutive d’une infraction pénale. Toute copie ou impression de ce fichier doit contenir la présente mention de copyright. Article numérisé dans le cadre du programme Numérisation de documents anciens mathématiques http://www.numdam.org/ Informatique théorique et Applications/Theoretical Informaties and Applications (vol. 26, n° 1, 1992, p. 93 à 113) INDEXED COUNTER LANGUAGES (*) by J. DUSKE (x), M. MIDDENDORF (*) and R. PARCHMANN (*) Communicated by J. BERSTEL Abstract. — Starting with the characterization of context-free counter languages by rightlinear indexed grammars with one index, indexed counter grammars are introduced and investigated. The family of indexed counter languages is a full AFL properly contained in the family of indexed languages and incomparable with the full trio oflinear indexed languages. Furthermore by modifying the dérivation mode, a characterization of type-0 languages by indexed counter grammars is given. Résumé. - Après une caractêrisation des langages algébriques à compteurs par des grammaires indexées linéaires droites d'index 1, on introduit et étudie les grammaires indexées à compteurs. La famille des langages indexés à compteurs est une AFL proprement contenue dans la famille des langages indexés, et incomparable au cône rationnel des langages indexés linéaires. -

Appendix A: Hierarchy of Grammar Formalisms

Appendix A: Hierarchy of Grammar Formalisms The following figure recalls the language hierarchy that we have developed in the course of the book. '' $$ '' $$ '' $$ ' ' $ $ CFG, 1-MCFG, PDA n n L1 = {a b | n ≥ 0} & % TAG, LIG, CCG, tree-local MCTAG, EPDA n n n ∗ L2 = {a b c | n ≥ 0}, L3 = {ww | w ∈{a, b} } & % 2-LCFRS, 2-MCFG, simple 2-RCG & % 3-LCFRS, 3-MCFG, simple 3-RCG n n n n n ∗ L4 = {a1 a2 a3 a4 a5 | n ≥ 0}, L5 = {www | w ∈{a, b} } & % ... LCFRS, MCFG, simple RCG, MG, set-local MCTAG, finite-copying LFG & % Thread Automata (TA) & % PMCFG 2n L6 = {a | n ≥ 0} & % RCG, simple LMG (= PTIME) & % mildly context-sensitive L. Kallmeyer, Parsing Beyond Context-Free Grammars, Cognitive Technologies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-14846-0, c Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2010 216 Appendix A For each class the different formalisms and automata that generate/accept exactly the string languages contained in this class are listed. Furthermore, examples of typical languages for this class are added, i.e., of languages that belong to this class while not belonging to the next smaller class in our hier- archy. The inclusions are all proper inclusions, except for the relation between LCFRS and Thread Automata (TA). Here, we do not know whether the in- clusion is a proper one. It is possible that both devices yield the same class of languages. Appendix B: List of Acronyms The following table lists all acronyms that occur in this book. (2,2)-BRCG Binary bottom-up non-erasing RCG with at most two vari- ables per left-hand side argument 2-SA Two-Stack Automaton -

A Hierarchy of Mildly Context-Sensitive Dependency Grammars Anssi Yli-Jyra¨ and Matti Nykanen¨

11 A Hierarchy of Mildly Context-Sensitive Dependency Grammars Anssi Yli-Jyra¨ and Matti Nykanen¨ Department of Modern Languages, University of Helsinki and School of Computing, University of Eastern Finland Email: Anssi.Yli-Jyra@helsinki.fi, Matti.Nykanen@uef.fi ABSTRACT. We generalize Link Grammars with crossing dependencies and pro- jective Dependency Grammars with a gradient projectivity condition and mul- tiple heads. The generalizations rely on right linear grammars that encode the links and dependencies via index storage instructions. The underlying machinery and the stepwise refinements of the definitions connect the generalized gram- mars to Linear Indexed Grammars and the mildly context sensitive hierarchy of Wartena’s right linear grammars that use composite index storages. The gradi- ent projectivity measure – the non-projectivty depth – relies on a normalized storage type whose runs represent particular multiplanar decompositions for de- pendency graphs. This decomposition does not aim at minimal graph coloring, but focuses, instead, to rigidly necessary color changes in right linear processing. Thanks to this multiplanar decomposition, every non-projectivity depth k charac- terizes strictly larger sets of acyclic dependency graphs and trees than the planar projective dependency graphs and trees. 11.1 Introduction In this paper, we generalize Link Grammars (Sleator and Temper- ley 1993) and projective Dependency Grammars (Hays 1964, Gaifman 1965) with crossing dependencies and then characterize the generaliza- tions using formal language theory. In terms of Dependency Grammars (DGs) (Tesni`ere1959), word- order is distinct from the dependency tree that analyzes the struc- ture of the sentence. However, Hays (1964) and Gaifman (1965) have Proceedings of Formal Grammar 2004. -

A Formal Model for Context-Free Languages Augmented with Reduplication

A FORMAL MODEL FOR CONTEXT-FREE LANGUAGES AUGMENTED WITH REDUPLICATION Walter J. Savitch Department of Computer Science and Engineering University of California, San Diego La Jolla, CA 92093 A model is presented to characterize the class of languages obtained by adding reduplication to context-free languages. The model is a pushdown automaton augmented with the ability to check reduplication by using the stack in a new way. The class of languages generated is shown to lie strictly between the context-free languages and the indexed languages. The model appears capable of accommodating the sort of reduplications that have been observed to occur in natural languages, but it excludes many of the unnatural constructions that other formal models have permitted. 1 INTRODUCTION formal language. Indeed, most of the known, convinc- ing arguments that some natural language cannot (or Context-free grammars are a recurrent theme in many, almost cannot) be weakly generated by a context-free perhaps most, models of natural language syntax. It is grammar depend on a reduplication similar to the one close to impossible to find a textbook or journal that exhibited by this formal language. Examples include the deals with natural language syntax but that does not respectively construct in English (Bar-Hillel and Shamir include parse trees someplace in its pages. The models 1964), noun-stem reduplication and incorporation in used typically augment the context-free grammar with Mohawk (Postal 1964), noun reduplication in Bambara some additional computational power so that the class (Culy 1985), cross-serial dependency of verbs and ob- of languages described is invariably larger, and often jects :in certain subordinate clause constructions in much larger, than the class of context-free languages. -

Indexed Languages and Unification Grammars*

21 Indexed Languages and Unification Grammars* Tore Burheim^ A bstract Indexed languages are interesting in computational linguistics because they are the least class of languages in the Chomsky hierarchy that has not been shown not to be adequate to describe the string set of natural language sent ences. We here define a class of unification grammars that exactly describe the class of indexed languages. 1 Introduction The occurrence of purely syntactical cross-serial dependencies in Swiss-German shows that context-free grammars can not describe the string sets of natural lan guage [Shi85]. The least class in the Chomsky hierarchy that can describe unlimited cross-serial dependencies is indexed grammars [Aho 68]. Gazdar discuss in [Gaz88] the applicability of indexed grammars to natural languages, and show how they can be used to describe different syntactic structures. We are here going to study how we can describe the class of indexed languages with a unification grammar formalism. After defining indexed grammars and a simple unification grammar framework we show how we can define an equivalent unification grammar for any given indexed grammar. Two grammars are equivalent if they generate the same language. With this background we define a class of unification grammars and show that this class describes the clciss of indexed languages. 2 Indexed grammars Indexed grammars is a grammar formalism with generative capacity between con text-free grammars and context-sensitive grammars. Context-free grammars can not describe cross-serial dependencies due to the pumping lemma, while indexed grammars can. However, the class of languages generated by indexed grammars, -the indexed languages, is a proper subset of context-sensitive languages [Aho 68].