Life After Death in Singapore's Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore, July 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Singapore, July 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: SINGAPORE July 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Singapore (English-language name). Also, in other official languages: Republik Singapura (Malay), Xinjiapo Gongheguo― 新加坡共和国 (Chinese), and Cingkappãr Kudiyarasu (Tamil) சி க யரச. Short Form: Singapore. Click to Enlarge Image Term for Citizen(s): Singaporean(s). Capital: Singapore. Major Cities: Singapore is a city-state. The city of Singapore is located on the south-central coast of the island of Singapore, but urbanization has taken over most of the territory of the island. Date of Independence: August 31, 1963, from Britain; August 9, 1965, from the Federation of Malaysia. National Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1); Lunar New Year (movable date in January or February); Hari Raya Haji (Feast of the Sacrifice, movable date in February); Good Friday (movable date in March or April); Labour Day (May 1); Vesak Day (June 2); National Day or Independence Day (August 9); Deepavali (movable date in November); Hari Raya Puasa (end of Ramadan, movable date according to the Islamic lunar calendar); and Christmas (December 25). Flag: Two equal horizontal bands of red (top) and white; a vertical white crescent (closed portion toward the hoist side), partially enclosing five white-point stars arranged in a circle, positioned near the hoist side of the red band. The red band symbolizes universal brotherhood and the equality of men; the white band, purity and virtue. The crescent moon represents Click to Enlarge Image a young nation on the rise, while the five stars stand for the ideals of democracy, peace, progress, justice, and equality. -

How to Get to Singapore Nursing Board by Public Transport (81 Kim Keat Road, #08-00, Singapore 328836)

How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by Public Transport (81 Kim Keat Road, #08-00, Singapore 328836) Bus Stop Number: 52411 (Blk 105 ) Bus Stop Number: 52499 (St. Michael Bus Terminal ) Jalan Rajah (After Global Indian International School) Whampoa Road Bus services : 139, 565 Bus Services : 21, 124, 125, 131, 186 Bus Stop Number: 52419 (Curtin S’pore ) Bus Stop Number: 52099 (Opp. NKF) Jalan Rajah Kim Keat Road Bus Services : 139 Bus Services : 21, 124, 125, 131, 139, 186, 565 How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by MRT and Bus Nearest MRT Station How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by MRT and Bus Toa Payoh Alight at NS19 – Toa Payoh MRT Station (Use Exit B) MRT Station Take Bus 139 at Toa Payoh Bus Interchange (52009) (NS19) Alight at Bus Stop Number: 52411 (Blk 105) – Jalan Rajah Number of Stops: 5 Walk towards NKF Centre (200m away) OR Alight at Bus Stop Number: 52099 (opp. NKF) –Kim Keat Road Number of Stops: 9 Cross the road and walk towards NKF Centre (50m away) Novena MRT Alight at NS20 – Novena MRT Station (Use Exit B2) How to get to SNB (Public Transport) 1 June 2011 Page 1 of 4 Nearest MRT Station How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by MRT and Bus Station Walk down towards Novena Church. (NS20) Walk across the overhead bridge, and walk towards Bus Stop Number: 50031 – Thomson Road (in front of Novena Ville). Take Bus 21 or 131 Alight at Bus Stop Number: 52499 (St. Michael Bus Terminal) –Whampoa Road Number of Stops: 10 Walk towards NKF Centre (110m away) Newton MRT Alight at NS21 – Newton MRT Station (Use Exit A) Station Take Bus 124 at Bus Stop Number: 40181 – Scotts Road (heading towards Newton (NS21) Road). -

Living Water

LIVING WITH WATER: LIVING WITH WATER: LESSONS FROM SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM Living with Water: Lessons from Singapore and Rotterdam documents the journey of two unique cities, Singapore and Rotterdam—one with too little water, and the other with too LESSONS FROM SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM LESSONS much water—in adapting to future climate change impacts. While the WITH social, cultural, and physical nature of these cities could not be more different, Living with Water: Lessons from Singapore and Rotterdam LIVING captures key principles, insights and innovative solutions that threads through their respective adaptation WATER: strategies as they build for an LESSONS FROM uncertain future of sea level rise and intense rainfall. SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM LIVING WITH WATER: LESSONS FROM SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM CONTENTS About the organisations: v • About the Centre for Liveable Cities v • About the Rotterdam Office of Climate Adaptation v Foreword by Minister for National Development, Singapore vi Foreword by Mayor of Rotterdam viii Preface by the Executive Director, Centre for Liveable Cities x For product information, please contact 1. Introduction 1 +65 66459576 1.1. Global challenges, common solutions 1 Centre for Liveable Cities 1.2. Distilling and sharing knowledge on climate-adaptive cities 6 45 Maxwell Road #07-01 The URA Centre 2. Living with Water: Rotterdam and Singapore 9 Singapore 069118 2.1. Rotterdam’s vision 9 [email protected] 2.1.1. Rotterdam’s approach: Too Much Water 9 2.1.2. Learning to live with more water 20 Cover photo: 2.2. A climate-resilient Singapore 22 Rotterdam (Rotterdam Office of Climate Adaptation) and “Far East Organisation Children’s Garden” flickr photo by chooyutshing 2.2.1. -

Tour Description World Express Offers a Wide Choice of Sightseeing Tours, Which Offer Visitors an Interesting Experience of the Sights and Sounds of Singapore

TOUR DESCRIPTION WORLD EXPRESS OFFERS A WIDE CHOICE OF SIGHTSEEING TOURS, WHICH OFFER VISITORS AN INTERESTING EXPERIENCE OF THE SIGHTS AND SOUNDS OF SINGAPORE 1 CITY TOUR 1 PERANAKAN TRAIL (with food tasting) SIN-1 3 /2 hrs SIN-4 3 /2 hrs An orientation tour that showcases the history, multi racial culture and lifestyle that is Join us on a colourful journey into the history, lifestyle and unique character of the SINGAPORE Singapore. Peranakan Babas (the men) and Nonyas (the women)… A walk through a Spice Garden – the original site of the first Botanic Gardens will uncover See the city’s colonial heritage as we drive around the Civic District past the Padang, the the intricacies of spices and herbs that go into Peranakan cooking. Cricket Club, Parliament House, Supreme Court and City Hall. Stop at the Merlion Park for great views of Marina Bay and a picture-taking opportunity with the Merlion, a mythological A splendid display of Peranakan costume, embroidery, beadwork, jewellery, porcelain, creature that is part lion and part fish. The tour continues with a visit to the Thian Hock furniture, craftwork will provide a glimpse into the fascinating culture of the Nonyas Keng Temple, one of the oldest Buddhist-Taoist temples on the island, built with donation and Babas. from the early immigrants workers from China. Next drive past Chinatown to a local handicraft centre to watch Asian craftsmanship. From there we proceed to the National A visit to the bustling enclaves of Katong & Joo Chiat showcases the rich and baroque Orchid Garden, located within the Singapore Botanic Gardens, which boasts a sprawling Peranakan architecture. -

Singapore Office

Singapore Office Contact Address NTT/Training Partners 12 Kallang Avenue, Aperia, The Annex, #04-28/29 Singapore 339511 Direction and Map Driving Instruction Public Transport Information via PIE Head east on PIE-Take exit 13 toward Sims Ave-Continue onto Sims Way - Turn right Nearest MRT: Lavender station, East West Line onto Geylang Rd-Continue onto Kallang Rd-Turn right onto Padang Jeringau-Continue onto Kallang Ave- Aperia will be on the left Bus : 13, 61, 67, 107, 107M, 133, 141, 145, 175, 961 via ECP Head west on ECP-Take exit 15 for Rochor Rd-Continue onto Rochor Rd - Turn right Walking directions to TP office within Aperia Mall onto Victoria St - Continue onto Kallang Rd -Turn left onto Padang Jeringau - Continue onto Kallang Ave - Aperia will be on the left. A: Access via Office/Link Mall Take the elevator (Opp. Cold Storage) to the 3rd floor of Lobby A, walk towards via KPE water display, turn right again, walk to unit #04-28 towards the left, take the Head south-Continue onto Sims Way-Turn right onto Geylang Rd - Continue onto staircase up to the 4th floor TP office. Kallang Rd - Turn right onto Padang Jeringau - Continue onto Kallang Ave - Aperia will be on the left B: Access via Retail Escalator to 3rd storey Enter Mall through main entrance, take the escalator to level 3, exit glass door next Car Park Information to the Time Enterprise TCM to the annex area, walk straight down to unit #04-28 on P the left, take the staircase up to the 4th floor TP office. -

Must Visit Attractions in Singapore"

"Must Visit Attractions in Singapore" Created by: Cityseeker 16 Locations Bookmarked Merlion Park "Singapore's National Emblem" Standing guard at the mouth of the Singapore River is the Merlion, a mythical beast that is a cross between a fish and a lion. The fish symbolizes Singapore's close association with the sea while the lion head refers to the legendary sighting of a lion during the discovery of ancient Singapore. Created in 1972 as a tourism icon, the Merlion is especially by Graham-H attractive in the evenings when it is illuminated and spouts water from its mouth. Today, it has moved 120 meters (393 feet) away from its original spot, adjacent to One Fullerton. A stroll through Merlion Park yields great views of Singapore's colonial district. +65 6736 6622 1 Fullerton Road, Singapore Marina Bay Sands Skypark "Experience Singapore from New Heights" A true marvel of engineering designed by the famous architect Moshe Safdie, the Marina Bay Sands Skypark is an open-air viewing deck perched 200 meters (656.168 feet) atop the Marina Bay Sands Hotel. This deck, shaped like a ship, almost seems to go against the law of gravity as it stretches on the 57th story above the hotel tower. The panoramic views by Sarah_Ackerman from of Singapore are staggering, and on a clear day, far-off islands belonging New York, USA. to Malaysia and Indonesia can be seen. The Skypark is the size of three football fields and also contains lush tropical gardens, souvenir stands and gourmet restaurants. Its main attraction is a spectacular infinity pool that seems as if it meets thin air at one of its longer edges. -

Kallang River to Be Rejuvenated

Kallang River to Be Rejuvenated On 29 March, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) launched a new exhibition titled “A River Runs Through It”. This exhibition is a call for public feedback on a preliminary conceptual plan to improve connectivity along the 14kmlong Kallang River, and to revitalise the areas around it. Minister for National Development and Second Minister for Finance Mr Lawrence Wong officiated at the launch of the exhibition. Potential for Rejuvenation Aerial view of possible enhancements along the Kallang River The Kallang River is Singapore’s longest natural river. Originating from Lower Peirce Reservoir, the river passes through many housing and industrial areas such as Ang Mo Kio, Bishan, Toa Payoh, Bendemeer, and Kallang Bahru before merging into the Kallang Basin. Some 800,000 people now live within 2km of the Kallang River. Over the next 20 years, there is potential to introduce another 100,000 dwelling units into the area. Waterfront rejuvenation started in the 1980s in Singapore, following the cleanup of both the Singapore River and the Kallang Basin. Over the past 30 years, the government has focused on the Singapore River, Marina Bay, and the Kallang Basin. The time is ripe to begin discussions about the further rejuvenation of the Kallang River. URA also hopes to upgrade underpasses and to build new ones in the area, including one under Sims Avenue that would help connect Kallang MRT station to the Singapore Sports Hub. Pedestrian crossings at Serangoon Road and Bendemeer Road are also expected to be widened to facilitate cycling. The existing CTE crossing could be widened and deepened for a more conducive environment for active mobility Currently, cyclists travelling along the Kallang River face several obstacles, including an 83step climb with their bicycles up a pedestrian overhead bridge across the PanIsland Expressway (PIE) and a 47 step descent on the other side. -

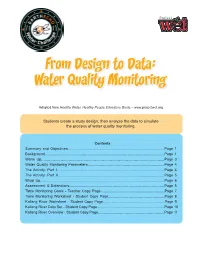

From Design to Data: Water Quality Monitoring

From Design to Data: Water Quality Monitoring Adapted from Healthy Water, Healthy People Educators Guide – www.projectwet.org Students create a study design, then analyze the data to simulate the process of water quality monitoring. Contents Summary and Objectives.....................................................................................Page 1 Background........................................................................................................Page 1 Warm Up............................................................................................................Page 3 Water Quality Monitoring Parameters....................................................................Page 4 The Activity: Part I...............................................................................................Page 4 The Activity: Part II..............................................................................................Page 5 Wrap Up............................................................................................................Page 6 Assessment & Extensions...................................................................................Page 6 Table Monitoring Goals - Teacher Copy Page.........................................................Page 7 Table Monitoring Worksheet - Student Copy Page..................................................Page 8 Kallang River Worksheet - Student Copy Page.......................................................Page 9 Kallang River Data Set - Student Copy Page.............................................................Page -

Hotel Address Postal Code 3D Harmony Hostel 23/25A Mayo

Changi Airport Transfer Hotel Address Postal Code 3D Harmony Hostel 23/25A Mayo Street S(208308) 30 Bencoolen Hotel 30 Bencoolen St S(189621) 5 Footway Inn Project Chinatown 2 227 South Bridge Road S(058776) 5 Footway Inn Project Ann Siang 267 South Bridge Road S(058816) 5 Footway Inn Project Chinatown 1 63 Pagoda St S(059222) 5 Footway Inn Project Bugis 8,10,12 Aliwal Street S(199903) 5 Footway Inn Project Boat Quay 76 Boat Quay S(049864) 7 Wonder Capsule Hostel 257 Jalan Besar S(208930) 38 Hongkong Street Hostel 38A Hong Kong Street S(059677) 60's Hostel 569 Serangoon Road S(218184) 60's Hostel 96A Lorong 27 Geylang S(388198) 165 Hotel 165 Kitchener Road S(208532) A Beary Best Hostel 16 & 18 Upper Cross Street S(059225) A Travellers Rest -Stop 5 Teck Lim Road S(088383) ABC Backpacker Hostel 3 Jalan Kubor (North Bridge Road) S(199201) ABC Premier Hostel 91A Owen Road S(218919) Adler Hostel 259 South Bridge Road S(058808) Adamson Inn Hotel 3 Jalan Pinang,Bugis S(199135) Adamson Lodge 6 Perak Road S(208127) Alis Nest Singapore 23 Robert Lane, Serangoon Road S(218302) Aliwal Park Hotel 77 / 79 Aliwal St. S(199948) Amara Hotel 165 Tanjong Pagar Road S(088539) Amaris Hotel 21 Middle Road S(188931) Ambassador Hotel 65-75 Desker Road S(209598) Amigo Hostel 55 Lavender Road S(338713) Amrise Hotel 112 Sims Avenue #01-01 S(387436) Amoy Hotel 76 Telok Ayer St S(048464) Andaz Singapore 5 Fraser Street S(189354) Aqueen Hotel Balestier 387 Balestier Road S(029795) Aqueen Hotel Lavender 139 Lavender St. -

Participating Merchants

PARTICIPATING MERCHANTS PARTICIPATING POSTAL ADDRESS MERCHANTS CODE 460 ALEXANDRA ROAD, #01-17 AND #01-20 119963 53 ANG MO KIO AVENUE 3, #01-40 AMK HUB 569933 241/243 VICTORIA STREET, BUGIS VILLAGE 188030 BUKIT PANJANG PLAZA, #01-28 1 JELEBU ROAD 677743 175 BENCOOLEN STREET, #01-01 BURLINGTON SQUARE 189649 THE CENTRAL 6 EU TONG SEN STREET, #01-23 TO 26 059817 2 CHANGI BUSINESS PARK AVENUE 1, #01-05 486015 1 SENG KANG SQUARE, #B1-14/14A COMPASS ONE 545078 FAIRPRICE HUB 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE, #01-51 629117 FUCHUN COMMUNITY CLUB, #01-01 NO 1 WOODLANDS STREET 31 738581 11 BEDOK NORTH STREET 1, #01-33 469662 4 HILLVIEW RISE, #01-06 #01-07 HILLV2 667979 INCOME AT RAFFLES 16 COLLYER QUAY, #01-01/02 049318 2 JURONG EAST STREET 21, #01-51 609601 50 JURONG GATEWAY ROAD JEM, #B1-02 608549 78 AIRPORT BOULEVARD, #B2-235-236 JEWEL CHANGI AIRPORT 819666 63 JURONG WEST CENTRAL 3, #B1-54/55 JURONG POINT SHOPPING CENTRE 648331 KALLANG LEISURE PARK 5 STADIUM WALK, #01-43 397693 216 ANG MO KIO AVE 4, #01-01 569897 1 LOWER KENT RIDGE ROAD, #03-11 ONE KENT RIDGE 119082 BLK 809 FRENCH ROAD, #01-31 KITCHENER COMPLEX 200809 Burger King BLK 258 PASIR RIS STREET 21, #01-23 510258 8A MARINA BOULEVARD, #B2-03 MARINA BAY LINK MALL 018984 BLK 4 WOODLANDS STREET 12, #02-01 738623 23 SERANGOON CENTRAL NEX, #B1-30/31 556083 80 MARINE PARADE ROAD, #01-11 PARKWAY PARADE 449269 120 PASIR RIS CENTRAL, #01-11 PASIR RIS SPORTS CENTRE 519640 60 PAYA LEBAR ROAD, #01-40/41/42/43 409051 PLAZA SINGAPURA 68 ORCHARD ROAD, #B1-11 238839 33 SENGKANG WEST AVENUE, #01-09/10/11/12/13/14 THE -

Singapore River

No tour of Singapore is complete without a leisurely trip along the Singapore River. More than any other waterway, the river has defined the island’s history as well as played a significant role in its commercial success. SKYSCRAPERS SEEN FROM SINGAPORE RIVER singapore river VICTORIA THEATRE & CONCERT HALL SUPREME COURT PADANG SINGAPORE RIVER SIR STAMFORD RAFFLES central 5 9 A great way to see the sights is to Kim, Robertson, Alkaff, book a river tour with the Clemenceau, Ord, Read, Singapore Explorer (Tel: 6339- Coleman, Elgin, Cavenagh, 6833). Begin your tour at Jiak Anderson and Esplanade — and Kim Jetty, just off Kim Seng in the process, pass through a Road, on either a bumboat (for significant slice of Singapore’s authenticity) or a glass-top boat history and a great many (for comfort). From here, you landmarks. will pass under 11 bridges — Jiak Robertson Quay is a quiet residential enclave that, in recent years, has seen the beginnings of a dining hub, with excellent restaurants and gourmet shops like La Stella, Saint Pierre, Coriander Leaf, Tamade and Epicurious, all within striking distance of each other. Close to the leafy coolness of Fort Canning as well as the jumping disco-stretch of Mohamed Sultan Road , the area offers a CLARKE QUAY more relaxed setting compared to its busier neighbour, Clarke Quay, downstream. With its vibrant and bustling concentration of pubs, seafood restaurants, street bazaars, live jazz bands, weekend flea markets and entertainment complexes, Clarke ROBERTSON QUAY Quay remains a magnet for tourists and locals. Restored in 1993, the sprawling village is open till late at night, filling the air with the warmth from the ROBERTSON QUAY CLARKE QUAY ROBERTSON QUAY/CLARKE QUAY charcoal braziers of the satay stalls (collectively called The Satay Club), the loud thump of discos and the general convivial air of relaxed bonhomie. -

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and Post-Colonial Singapore Reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and post-colonial Singapore reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus by Sandra Hudd, B.A., B. Soc. Admin. School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, September 2015 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the Universityor any other institution, except by way of backgroundi nformationand duly acknowledged in the thesis, andto the best ofmy knowledgea nd beliefno material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text oft he thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. �s &>-pt· � r � 111 Authority of Access This thesis is not to be made available for loan or copying fortwo years followingthe date this statement was signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available forloan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. :3 £.12_pt- l� �-- IV Abstract By tracing the transformation of the site of the former Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, this thesis connects key issues and developments in the history of colonial and postcolonial Singapore. The convent, established in 1854 in central Singapore, is now the ‗premier lifestyle destination‘, CHIJMES. I show that the Sisters were early providers of social services and girls‘ education, with an orphanage, women‘s refuge and schools for girls. They survived the turbulent years of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and adapted to the priorities of the new government after independence, expanding to become the largest cloistered convent in Southeast Asia.