Momma's Gotta' Let Go: a Character-Driven Analysis of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Into the Woods Is Presented Through Special Arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI)

PREMIER SPONSOR ASSOCIATE SPONSOR MEDIA SPONSOR Music and Lyrics by Book by Stephen Sondheim James Lapine June 28-July 13, 2019 Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Original Broadyway production by Heidi Landesman Rocco Landesman Rick Steiner M. Anthony Fisher Frederic H. Mayerson Jujamcyn Theatres Originally produced by the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, CA. Scenic Design Costume Design Shoko Kambara† Megan Rutherford Lighting Design Puppetry Consultant Miriam Nilofa Crowe† Peter Fekete Sound Design Casting Director INTO The Jacqueline Herter Michael Cassara, CSA Woods Musical Director Choreographer/Associate Director Daniel Lincoln^ Andrea Leigh-Smith Production Stage Manager Production Manager Myles C. Hatch* Adam Zonder Director Michael Barakiva+ Into the Woods is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com Music and Lyrics by Book by STEPHEN JAMES Directed by SONDHEIM LAPINE MICHAEL * Member of Actor’s Equity Association, † USA - Member of Originally directed on Broadway by James LapineBARAKIVA the Union of Professional Actors and United Scenic Artists Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Stage Managers in the United States. Local 829. ^ Member of American Federation of Musicians, + Local 802 or 380. CAST NARRATOR ............................................................................................................................................HERNDON LACKEY* CINDERELLA -

Cynthia Erivo to Receive the 'Rising Star' Award at The

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CYNTHIA ERIVO TO RECEIVE THE ‘RISING STAR’ AWARD AT THE 2020 AMERICAN BLACK FILM FESTIVAL HONORS Show Returns to Los Angeles Sunday, February 23, 2020 #ABFFHonors November 26, 2019, Los Angeles, CA – Today, ABFF Ventures announced Cynthia Erivo will receive the “Rising Star Award” at the 2020 ABFF Honors. The fourth annual ceremony, hosted by actor and comedian Deon Cole, will take place on Sunday, February 23, 2020 at the Beverly Hilton in Los Angeles. ABFF Honors is the American Black Film Festival’s awards season gala dedicated to saluting excellence in the motion picture and television industry. The event celebrates Black culture by paying tribute to individuals who have made significant contributions to American entertainment through their work, as well as those who champion diversity and inclusion in Hollywood. In addition to the acclamations, the show presents a competitive award for “Movie of the Year” and a “Classic Television Award” in recognition of a time-honored series that has made an indelible impact on audiences. Each year, ABFF Honors presents a “Rising Star Award” in recognition of an individual’s recent success and future promise in the film and television industry. Previous recipients have included Tiffany Haddish (Kids Say the Darndest Things), Issa Rae (Insecure) and Ryan Coogler (Black Panther). Cynthia Erivo is a Tony®, Emmy®, and Grammy® award-winning actress who burst onto West End and Broadway stages in The Color Purple and has taken the big screen by storm. Erivo’s film debut was in 2018 in Drew Goddard’s Bad Times at the El Royale. -

The Nineteenth-Century Russian Gypsy Choir and the Performance of Otherness

The Nineteenth-Century Russian Gypsy Choir and the Performance of Otherness Erik R. Scott Summer 2008 Erik R. Scott is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History, at the University of California, Berkeley Acknowledgments I would like to thank Professor Victoria Frede and my fellow graduate students in her seminar on Imperial Russian History. Their careful reading and constructive comments were foremost in my mind as I conceptualized and wrote this paper, first for our seminar in spring 2006, now as a revised work for publication. Abstract: As Russia’s nineteenth-century Gypsy craze swept through Moscow and St. Petersburg, Gypsy musicians entertained, dined with, and in some cases married Russian noblemen, bureaucrats, poets, and artists. Because the Gypsies’ extraordinary musical abilities supposedly stemmed from their unique Gypsy nature, the effectiveness of their performance rested on the definition of their ethnic identity as separate and distinct from that of the Russian audience. Although it drew on themes deeply embedded in Russian— and European—culture, the Orientalist allure of Gypsy performance was in no small part self-created and self-perpetuated by members of Russia’s renowned Gypsy choirs. For it was only by performing their otherness that Gypsies were able to seize upon their specialized role as entertainers, which gave this group of outsiders temporary control over their elite Russian audiences even as the songs, dances, costumes, and gestures of their performance were shaped perhaps more by audience expectations than by Gypsy musical traditions. The very popularity of the Gypsy musical idiom and the way it intimately reflected the Russian host society would later bring about a crisis of authenticity that by the end of the nineteenth century threatened the magical potential of Gypsy song and dance by suggesting it was something less than the genuine article. -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

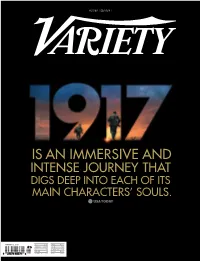

Is an Immersive and Intense Journey That Digs Deep Into Each of Its Main Characters’ Souls

ADVERTISEMENT IS AN IMMERSIVE AND INTENSE JOURNEY THAT DIGS DEEP INTO EACH OF ITS MAIN CHARACTERS’ SOULS. JANUARY 2, 2020 US $9.99 JAPAN ¥1280 CANADA $11.99 CHINA ¥80 UK £ 8 HONG KONG $95 EUROPE €9 RUSSIA 400 AUSTRALIA $14 INDIA 800 3 GOLDEN GLOBE® NOMINATIONS INCLUDING DRAMA BEST DIRECTOR BEST PICTURE SAM MENDES CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARDS NOMINATIONS INCLUDING 8 BEST DIRECTOR BEST PICTURE SAM MENDES THE BEST OF THE LIKE NO FILM YOU A MASTERWORK OF PICTURE YEAR IS HAVE SEEN. THE FIRST ORDER. YOU COULDN’T LOOK AWAY IF YOU WANTED TO. GOLDEN GLOBES YEARS HER MOMENT FOLLOWING ACCLAIMED ROLES IN ‘BOMBSHELL’ AND ‘ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD,’ ACTOR-PRODUCER MARGOT ROBBIE STORMS THE NEW YEAR WITH A FLURRY OF CREATIVE ENDEAVORS BY KATE AURTHUR P.5 0 P.50 Hollywood on Her Terms Margot Robbie is charging ahead as both an actor and a producer, carving a path for other women along the way. By KATE AURTHUR P.58 Creative Champion AMC Networks programming chief Sarah Barnett competes with streamers by nurturing creators of new cultural hits. By DANIEL HOLLOWAY P.62 Variety Digital Innovators 2020 Twelve leading minds in tech and entertainment are honored for pushing content boundaries. By TODD SPANGLER and JANKO ROETTGERS HANEL; HAIR: BRYCE SCARLETT/THE WALL GROUP/MOROCCAN OIL; MANICURE: TOM BACHIK; DRESS: CHANEL BACHIK; OIL; MANICURE: TOM GROUP/MOROCCAN WALL SCARLETT/THE HANEL; HAIR: BRYCE VARIETY.COM JANUARY 2, 2020 JANUARY (COVER AND THIS PAGE) PHOTOGRAPHS BY ART STREIBER; WARDROBE: KATE YOUNG/THE WALL GROUP; MAKEUP: PATI DUBROFF/FORWARD ARTISTS/C -

NETC News, Vol. 15, No. 3, Summer 2006

A Quarterly Publication of the New England Theater NETCNews Conference, Inc. volume 15 number 3 summer 2006 The Future is Now! NETC Gassner Competition inside Schwartz and Gleason Among 2006 a Global Event this issue New Haven Convention Highlights April 15th wasn’t just income tax day—it was also the by Tim Fitzgerald, deadline for mailing submissions for NETC’s John 2006 Convention Advisor/ Awards Chairperson Gassner Memorial Playwrighting Award. The award Area News was established in 1967 in memory of John Gassner, page 2 Mark your calendars now for the 2006 New England critic, editor and teacher. More than 300 scripts were Theatre Conference annual convention. The dates are submitted—about a five-fold increase from previous November 16–19, and the place is Omni New Haven years—following an extensive promotional campaign. Opportunities Hotel in the heart of one of the nation’s most exciting page 5 theatre cities—and just an hour from the Big Apple itself! This promises to be a true extravanganza, with We read tragedies, melodramas, verse Ovations workshops and inteviews by some of the leading per- dramas, biographies, farces—everything. sonalities of current American theatre, working today Some have that particular sort of detail that page 6 to create the theatre of tomorrow. The Future is Now! shows that they’re autobiographical, and Upcoming Events Our Major Award recipient this others are utterly fantastic. year will be none other than page 8 the Wicked man himself, Stephen Schwartz. Schwartz is “This year’s submissions really show that the Gassner an award winning composer Award has become one of the major playwrighting and lyricist, known for his work awards,” said the Gassner Committee Chairman, on Broadway in Wicked, Pippin, Steve Capra. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

GYPSY CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS: • Momma Rose

GYPSY CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS: • Momma Rose (age from 35 - 50) The ultimate stage mother. Lives her life vicariously through her two daughters, whom she's put into show business. She is loud, brash, pushy and single- minded, but at times can be doting and charming. She is holding down demons of her own that she is afraid to face. Her voice is the ultimate powerful Broadway belt. Minimal dance but must move well. Comic timing a must. Strong Mezzo/Alto with good low notes and belt. • Baby June (age 9-10) is a Shirley Temple-like up-and-coming vaudeville star, and Madam Rose's youngest daughter. Her onstage demeanor is sugary-sweet, cute, precocious and adorable to the nth degree. Needs to be no taller than 3', 5". An adorable character - Mama Rose's shining star. Strong child singer, strong dancer. Mezzo. • Young Louise (about 12) She should look a couple years older than Baby June. She is Madam Rose's brow-beaten oldest daughter, and has always played second fiddle to her baby sister. She is shy, awkward, a little sad and subdued; she doesn't have the confidence of her sister. Strong acting skills needed. The character always dances slightly out of step but the actress playing this part must be able to dance. Mezzo singer. • Herbie (about 45) agent for Rose's children and Rose's boyfriend and a possible husband number 4. He has a heart of gold but also has the power to defend the people he loves with strength. Minimum dance. A Baritone, sings in one group number, two duets and trio with Rose and Louise. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Musical! Theatre!

Premier Sponsors: Sound Designer Video Producer Costume Coordinator Lance Perl Chrissy Guest Megan Rutherford Production Stage Manager Assistant Stage Manager Stage Management Apprentice Mackenzie Trowbridge* Kat Taylor Lyndsey Connolly Production Manager Dramaturg Assistant Director Adam Zonder Hollyann Bucci Jacob Ettkin Musical Director Daniel M. Lincoln Directors Gerry McIntyre+ & Michael Barakiva+ We wish to express our gratitude to the Performers’ Unions: ACTORS’ EQUITY ASSOCIATION AMERICAN GUILD OF MUSICAL ARTISTS AMERICAN GUILD OF VARIETY ARTISTS SAG-AFTRA through Theatre Authority, Inc. for their cooperation in permitting the Artists to appear on this program. * Member of the Actor's Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. + ALEXA CEPEDA is delighted to be back at The KRIS COLEMAN* is thrilled to return to the Hangar. Hangar! Select credits: Mamma Mia (CFRT), A Broadway Credit: Jersey Boys (Barry Belson) Chorus Line (RTP), In The Heights (The Hangar Regional Credit: Passing Strange (Narrator), Jersey Theatre), The Fantasticks (Skinner Boys - Las Vegas (Barry Belson), Chicago (Hangar Barn), Cabaret (The Long Center), Anna in the Theatre, Billy Flynn), Dreamgirls (Jimmy Early), Sister Tropics (Richard M Clark Theatre). She is the Act (TJ), Once on This Island (Agwe), A Midsummer founder & host of Broadway Treats, an annual Nights Dream (Oberon) and Big River (Jim). benefit concert organized to raise funds for Television and film credits include: The Big House Animal Lighthouse Rescue (coming up! 9/20/20), and is (ABC), Dumbbomb Affair, and The Clone. "As we find ourselves currently working on her two-person musical Room 123. working through a global pandemic and race for equality, work Proud Ithaca College BFA alum! "Gracias a mamacita y papi." like this shows the value and appreciation for all.