Section 2 Historical Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING and DISEASE in FIRST NATIONS on RESERVE JULY 26, 2021 *The Reports Covers COVID-19 Testing Since the First Reported Case

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE JULY 26, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Monday July 19, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 252 Recovered Cases 240 New Cases 1 Active Cases 4 Total Deaths 8 FARHA Total Cases 1833 Recovered Cases 1814 New Cases 1 Active Cases 8 Total Deaths 11 Independent-North Total Cases 991 Recovered Cases 977 New Cases 0 Active Cases 4 Total Deaths 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. JULY 26, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 425 Recovered Cases 348 New Cases 36 Active Cases 74 Total Deaths 3 IRTC Total Cases 651 Recovered Cases 601 New Cases 11 Active Cases 38 Total Deaths 12 KTC Total Cases 1306 Recovered Cases 1281 New Cases 1 Active Cases 15 Total Deaths 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. JULY 26, 2021 SERDC Total Cases 737 Recovered Cases 697 New Cases 14 Active Cases 31 Total Deaths 9 SCTC Total Cases 1989 Recovered Cases 1940 New Cases 11 Active Cases 31 Total Deaths 18 WRTC Total Cases 377 Recovered Cases 348 New Cases 2 Active Cases 25 Total Deaths 4 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Keeyask Generation Project April 2014

REPORT ON PUBLIC HEARING Keeyask Generation Project April 2014 REPORT ON PUBLIC HEARING Keeyask Generation Project April 2014 ii iii iv Table of Contents Foreword . xi Executive Summary . xv Chapter One: Introduction. .1 1.1 Th e Manitoba Clean Environment Commission. .1 1.2 Th e Project . .1 1.3 Th e Proponent. .2 1.4 Terms of Reference . .3 1.5 Th e Hearings . .4 1.6 Th e Report. .4 Chapter Two: The Licensing Process . .7 2.1 Needed Licences and Approvals . .7 2.2 Review Process for an Environment Act Licence . .7 2.3 Federal Regulatory Review and Decision Making . .8 2.4 Section 35 of Canada’s Constitution. .8 2.5 Need For and Alternatives To. .9 2.6 Role of the Clean Environment Commission . .9 2.7 Th e Licensing Decision. .9 Chapter Three: The Public Hearing Process. 11 3.1 Clean Environment Commission . 11 3.2 Public Participation . 11 3.2.1 Participants . 11 3.2.2 Participant Assistance Program . 11 3.2.3 Presenters. 12 3.3 Th e Pre-Hearing . 12 3.4 Th e Hearings . 12 v Chapter Four: Manitoba’s Electrical Generation and Transmission System . 13 4.1 System Overview. 13 4.2 Generating Stations . 15 4.3 Lake Winnipeg Regulation and the Churchill River Diversion. 17 Chapter Five: The Keeyask Generation Project. 21 5.1 Overview. 21 5.2 Major Project Components and Infrastructure. 23 5.2.1 Powerhouse . 23 5.2.2 Spillway . 24 5.2.3 Dams . 24 5.2.4 Dykes . 24 5.2.5 Ice Boom . -

Appendix 1 What We Heard from Policy Communities

Appendix 1 What we heard from policy communities Background In the Terms of Reference issued by the Minister of Conservation on September 1 2011, the Clean Environment Commission was asked to “hear evidence from Manitobans regarding the impacts of Lake Winnipeg regulation since the project was put into commercial use by Manitoba Hydro on August 1, 1976.” Over the period of approximately one month (January 12, 2015 to February 18, 2015), the Clean Environment Commission (CEC) attended 17 communities surrounding Lake Winnipeg.1 They also held two evening public sessions in Winnipeg and received a number of written submissions from the public.2 The CEC heard from many residents and users around the Lake including: cottage owners, permanent residents, Indigenous people, agricultural farmers, commercial and subsistence fishermen, and people and organizations from the tourism and recreation industry. There is disagreement in terms of the implications of Lake Winnipeg Regulation on Lake Winnipeg. Manitoba Hydro argues that its effects are generally either positive, benign or insignificant. Others take the position that LWR in conjunction with other Hydro activities has adverse and ongoing effect on the Lake. Among the prominent concerns are: • Lack of confidence in Manitoba Hydro, the Province and the CEC Hearing process on LWR • Lack of transparency of Manitoba Hydro and Manitoba Government operations of LWR • Lack of meaningful ongoing engagement • Sense of exclusion by upstream, downstream and Indigenous people • A sense that Manitoba hydro -

Schedule 15-2 Listed Agreements

SCHEDULE 15-2 LISTED AGREEMENTS 1. The Northern Flood Agreement between Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Manitoba, The Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board, The Northern Flood Committee, and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, dated December 16, 1977. 2. The Agreement Among Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Manitoba, The Split Lake Cree First Nation and The Manitoba Hydro- Electric Board, dated June 24, 1992. 3. The Comprehensive Implementation Agreement among Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Manitoba, The York Factory First Nation and The Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board, dated December 8, 1995. 4. The Comprehensive Implementation Agreement among Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Manitoba, The Nelson House First Nation and The Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board, dated March 15, 1996. 5. The Article 2 Implementation Agreement between Split Lake Cree First Nation and The Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board dated May 14, 1996. 6. The Norway House Cree Nation Master Implementation Agreement among Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Manitoba, The Norway House Cree Nation and The Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board, dated December 31, 1997. 7. The War Lake First Nation Past Adverse Effects Agreement between War Lake First Nation, Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Manitoba, and The Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board, dated March 30, 2005. 8. The Fox Lake First Nation Impact Settlement Agreement between the Fox Lake First Nation, Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Manitoba, and The Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board, dated December 6, 2004. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

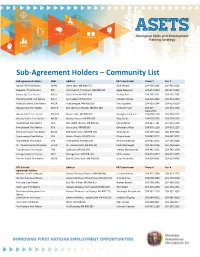

Sub-‐Agreement Holders – Community List

Sub-Agreement Holders – Community List Sub-Agreement Holders Abbr. Address E&T Coordinator Phone # Fax # Garden Hill First Nation GHFN Island Lake, MB R0B 0T0 Elsie Monias 204-456-2085 204-456-9315 Keewatin Tribal Council KTC 23 Nickel Rd, Thompson, MB R8N 0Y4 Aggie Weenusk 204-677-0399 204-677-0257 Manto Sipi Cree Nation MSCN God's River, MB R0B 0N0 Bradley Ross 204-366-2011 204-366-2282 Marcel Colomb First Nation MCFN Lynn Lake, MB R0B 0W0 Noreena Dumas 204-356-2439 204-356-2330 Mathias Colomb Cree Nation MCCN Pukatawagon, MB R0B 1G0 Flora Bighetty 204-533-2244 204-553-2029 Misipawistik Cree Nation MCN'G Box 500 Grand Rapids, MB R0C 1E0 Melina Ferland 204-639- 204-639-2503 2491/2535 Mosakahiken Cree Nation MCN'M Moose Lake, MB R0B 0Y0 Georgina Sanderson 204-678-2169 204-678-2210 Norway House Cree Nation NHCN Norway House, MB R0B 1B0 Tony Scribe 204-359-6296 204-359-6262 Opaskwayak Cree Nation OCN Box 10880 The Pas, MB R0B 2J0 Joshua Brown 204-627-7181 204-623-5316 Pimicikamak Cree Nation PCN Cross Lake, MB R0B 0J0 Christopher Ross 204-676-2218 204-676-2117 Red Sucker Lake First Nation RSLFN Red Sucker Lake, MB R0B 1H0 Hilda Harper 204-469-5042 204-469-5966 Sapotaweyak Cree Nation SCN Pelican Rapids, MB R0B 1L0 Clayton Audy 204-587-2012 204-587-2072 Shamattawa First Nation SFN Shamattawa, MB R0B 1K0 Jemima Anderson 204-565-2041 204-565-2606 St. Theresa Point First Nation STPFN St. Theresa Point, MB R0B 1J0 Curtis McDougall 204-462-2106 204-462-2646 Tataskweyak Cree Nation TCN Split Lake, MB R0B 1P0 Yvonne Wastasecoot 204-342-2951 204-342-2664 -

Community Liaison Program: Bridging Land-Use Perspectives of First Nation Communities and the Minerals Resource Sector in Manitoba by L.A

GS-19 Community liaison program: bridging land-use perspectives of First Nation communities and the minerals resource sector in Manitoba by L.A. Murphy Murphy, L.A. 2011: Community liaison program: bridging land-use perspectives of First Nation communities and the minerals resource sector in Manitoba; in Report of Activities 2011, Manitoba Innovation, Energy and Mines, Manitoba Geological Survey, p. 180–181. Summary Model Forest Junior Rangers The Manitoba Geological Survey (MGS) community program, Nopiming Provincial liaison program provides a geological contact person Park on the east side of Lake for Manitoba First Nation communities and the Winnipeg (Figure GS-19-1) minerals resource sector. The mandate for this program Red Sucker Lake First Nation in the Island Lake acknowledges and respects the First Nation land-use traditional land-use area perspective, allows for an open exchange of mineral Bunibonibee Cree Nation in the Oxford House information, and encourages the integration of geology traditional land-use area and mineral-resource potential into the land-use planning Sapotaweyak First Nation Community Interest Zone process. Timely information exchange is critical to all Gods Lake First Nation in Gods Lake Narrows stakeholders, and open communication of all concerns Tataskweyak Cree Nation in Split Lake regarding multiple land-use issues reduces timelines and mitigates potential impacts to Aboriginal and Treaty rights. Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Inc. (MKO) Schools, communities and mineral industry stakeholders representing Manitoba’s northern First Nations and throughout Manitoba access the program during land-use Tribal councils planning processes, encouraging a balanced approach to College Pierre-Elliot-Trudeau, Transcona School economic development in traditional land-use areas. -

MKO Grand Chief

Updated December 16, 2019 MANITOBA KEEWATINOWI OKIMAKANAK INC. MKO Grand Chief: Garrison Settee - MKO Executive Director: Kelvin Lynxleg ADMINISTRATION OFFICE WINNIPEG OFFICE 206 – 55 Selkirk Avenue Suite 1601-275 Portage Avenue Thompson, MB R8N 0M5 Winnipeg, MB R3B 2B3 Phone: (204) 677-1600 Phone: (204) 927-7500 Fax: (204) 778-7655 Fax:(204) 927-7509 MKO Member First Nations & Tribal Council Affiliations – Members of the Executive Council www.mkonation.com Independent First Nations Chief Oliver Okemow Chief Clarence Easter MANTO SIPI CREE NATION CHEMAWAWIN CREE NATION Chief Marcel Moody God’s River, MB ROB ONO Easterville, MB ROC 0V0 NISICHAWAYASIHK CREE NATION Phone: 366-2011 Fax: 366-2282 Phone: 329-2161 Fax: 329-2017 Nelson House, MB ROB 1A0 Phone: 484-2332 Fax: 484-2392 Chief Billy Beardy Chief Jim Tobacco FOX LAKE CREE NATION MOSAKAHIKEN FIRST NATION Chief Larson R. Anderson Box 369 Moose Lake, MB ROB OYO NORWAY HOUSE CREE NATION Gilliam, MB ROB OLO Phone: 678-2113 Fax: 678-2292 Norway House, MB R0B 1B0 Phone: 486-2463 Fax: 486-2503 Phone: 359-6786 Fax: 359-4186 Recognized by the MKO Chiefs in Assembly as Chief Doreen Spence a First Nation and as a Member of MKO Chief David Monias TATASKWEYAK CREE NATION PIMICIKAMAK CREE NATION Split Lake, MB ROB 1PO Headman Clarence Bighetty Cross Lake, MB ROB OJO Phone: 342-2045 Fax: 342-2270 GRANVILLE LAKE FIRST NATION Phone: 676-3133 Fax: 676-3155 Leaf Rapids, MB R0B 1W0 Chief Betsy Kennedy Phone: 204-473-6002 Chief Shirley Ducharme WAR LAKE FIRST NATION Email: [email protected] O-PIPON-NA-PIWIN -

Makeso Sakahikan Inninuwak• Fox Lake Cree Nation

Makeso Sakahikan Inninuwak• Fox Lake Cree Nation Makeso Sakahikan Inninuwak• Fox Lake Cree Nation A Participant Review of the Manitoba and Manitoba Hydro Regional Cumulative Effects Assessment (RCEA) Phase II Report October 2, 2017 Makeso Sakahikan Inninuwak• Fox Lake Cree Nation Executive Summary On April 25, 2017, the Clean Environment Commission (CEC) approved funding in the amount of $28,000.00 to prepare a written submission that addresses whether the cumulative effects of 50+ years of hydro development is accurately reflected in the RCEA documentation as it relates to the Fox Lake Cree Nation (FLCN) and to provide suggestions for future action. This submission was prepared with input from the community of Fox Lake. It describes details of the process and context in which the review was conducted and provides recommendations for future actions. The results of the review are presented as local cumulative effects and are divided into four categories: - Nipi•Water; - Nipi | Aski•Land and Water; - Future Development and, - Heritage and Mino Pimatisowin. The Community Profile is also reviewed and recommendations are made throughout the document from the information collected for this submission. The submission received feedback from Fox Lake Elders, resource users and members during a community meeting about the local cumulative effects of past, present and future hydroelectric and other developments contained in the RCEA Phase II Report. This approach was used to gain an understanding of how members have observed past effects and what information needs to be emphasized in a response to the CEC. The following is a list of recommendations presented in the review: To enhance the information already presented by Manitoba Hydro. -

Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge Monitoring Report – WLFN

War Lake First Nation Keeyask Generation Project ATK Monitoring Program Report (May 2019-March 2020) June 2020 Table of Contents 1.0 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 ABORIGINAL TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE ................................................................................................................ 2 1.2 CREE NATION PARTNERS ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION .......................................................................................... 3 1.3 KEEYASK ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION PLAN ........................................................................................................ 3 2.0 WAR LAKE ATK MONITORING PROGRAM .................................................................................................. 5 2.1 OBJECTIVES ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.3 CARIBOU MONITORING ...................................................................................................................................... 6 2.4 ATK MONITORING TRIPS .................................................................................................................................... 7 2.5 RESOURCE USERS ROUNDTABLES ........................................................................................................................