The Following Article Originally Appeared in Pro! and Is Reprinted Here by Permission of the Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL UCLA FOOTBALL AWARDS Henry R

2005 UCLA FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE NON-PUBLISHED SUPPLEMENT UCLA CAREER LEADERS RUSHING PASSING Years TCB TYG YL NYG Avg Years Att Comp TD Yds Pct 1. Gaston Green 1984-87 708 3,884 153 3,731 5.27 1. Cade McNown 1995-98 1,250 694 68 10,708 .555 2. Freeman McNeil 1977-80 605 3,297 102 3,195 5.28 2. Tom Ramsey 1979-82 751 441 50 6,168 .587 3. DeShaun Foster 1998-01 722 3,454 260 3,194 4.42 3. Cory Paus 1999-02 816 439 42 6,877 .538 4. Karim Abdul-Jabbar 1992-95 608 3,341 159 3,182 5.23 4. Drew Olson 2002- 770 422 33 5,334 .548 5. Wendell Tyler 1973-76 526 3,240 59 3,181 6.04 5. Troy Aikman 1987-88 627 406 41 5,298 .648 6. Skip Hicks 1993-94, 96-97 638 3,373 233 3,140 4.92 6. Tommy Maddox 1990-91 670 391 33 5,363 .584 7. Theotis Brown 1976-78 526 2,954 40 2,914 5.54 7. Wayne Cook 1991-94 612 352 34 4,723 .575 8. Kevin Nelson 1980-83 574 2,687 104 2,583 4.50 8. Dennis Dummit 1969-70 552 289 29 4,356 .524 9. Kermit Johnson 1971-73 370 2,551 56 2,495 6.74 9. Gary Beban 1965-67 465 243 23 4,087 .522 10. Kevin Williams 1989-92 418 2,348 133 2,215 5.30 10. Matt Stevens 1983-86 431 231 16 2,931 .536 11. -

Collecting Lombardi's Dominating Packers

Collecting Lombardi’s Dominating Packers BY DAVID LEE ince Lombardi called Lambeau Field his “pride and joy.” Specifically, the ground itself—the grass and the dirt. V He loved that field because it was his. He controlled everything that happened there. It was the home where Lombardi built one of the greatest sports dynasties of all-time. Fittingly, Lambeau Field was the setting for the 1967 NFL Champion- ship, famously dubbed “The Ice Bowl” before the game even started. Tem- peratures plummeting to 12 degrees below zero blasted Lombardi’s field. Despite his best efforts using an elaborate underground heating system to keep it from freezing, the field provided the perfect rock-hard setting to cap Green Bay’s decade of dominance—a franchise that bullied the NFL for nine seasons. The messy game came down to a goal line play of inches with 16 seconds left, the Packers trailing the Cowboys 17-14. Running backs were slipping on the ice, and time was running out. So, quarterback Bart Starr called his last timeout, and ran to the sideline to tell Lombardi he wanted to run it in himself. It was a risky all-in gamble on third down. “Well then run it, and let’s get the hell out of here,” Starr said Lom- bardi told him. The famous lunge into the endzone gave the Packers their third-straight NFL title (their fifth in the decade) and a second-straight trip to the Super Bowl to face the AFL’s best. It was the end of Lombardi’s historic run as Green Bay’s coach. -

2016 Preseason Honors

2016 preseason honors PRESEASON ALL-PAC 12 CONFERENCE CB CHIDOBE AWUZIE (first-team: collegesportsmadness.com; second-team: Athlon Sports, Lindy’s College Football, Phil Steele’s College Football) DT JORDAN CARRELL (fourth-team: Phil Steele’s College Football) ILB RICK GAMBOA (third-team: Lindy’s College Football) ILB ADDISON GILLAM (third-team: collegesportsmadness.com; fourth-team: Athlon Sports; Phil Steele’s College Football) OT JEROMY IRWIN (third-team: Phil Steele’s College Football) C ALEX KELLEY (fourth-team: Athlon Sports) P ALEX KINNEY (third-team: Athlon Sports, collegesportsmadness.com; fourth-team: Phil Steele’s College Football) OG TIM LYNOTT, Jr. (third-team: Phil Steele’s College Football) OLB DEREK McCARTNEY (third-team: Athlon Sports, Lindy’s College Football) S TEDRIC THOMPSON (third-team: Athlon Sports, Phil Steele’s College Football, collegesportsmadness.com) DT JOSH TUPOU (third-team: Phil Steele’s College Football, collegesportsmadness.com; fourth-team: Athlon Sports) BUFFALOES ON NATIONAL AWARD LISTS (WATCH LISTS/Nominations) Chuck Bednarik Award (defensive player of the year): CB Chidobe Awuzie (one of 90 on official watch list) Earl Campbell Tyler Rose Award (most outstanding offensive player with ties to state of Texas): SE Sean Irwin (CU’s nomination for the award) Paul Hornung Award (most versatile player): WR Donovan Lee (one of 43 on official watch list) Bronko Nagurski Award (defensive player of the year): CB Chidobe Awuzie (one of 88 on official watch list) Jim Thorpe Award (top defensive back): CB Chidobe Awuzie (one of 39 on official watch list) Doak Walker (top running back): TB Phillip Lindsay (one of 76 on official watch list) Danny Wuerffel Award (athletic, academic & community achievement): QB Sefo Liufau (one of 88 on official watch list) CB Chidobe Awuzie AFCA Good Words Team (community service; 12 are honored): OLB Derek McCartney (one of 81 official nominations) NATIONAL TOP 100 PLAYER RATINGS Cornerbacks: Chidobe Awuzie (No. -

04 Coaches-WEB.Pdf

59 Experience: 1st season at FSU/ Taggart jumped out to a hot start at Oregon, leading the Ducks to a 77-21 win in his first 9th as head coach/ game in Eugene. The point total tied for the highest in the NCAA in 2017, was Oregon’s 20th as collegiate coach highest since 1916 and included a school-record nine rushing touchdowns. The Hometown: Palmetto, Florida offensive fireworks continued as Oregon scored 42 first-half points in each of the first three games of the season, marking the first time in school history the program scored Alma Mater: Western Kentucky, 1998 at least 42 points in one half in three straight games. The Ducks began the season Family: wife Taneshia; 5-1 and completed the regular season with another offensive explosion, defeating rival sons Willie Jr. and Jackson; Oregon State 69-10 for the team’s seventh 40-point offensive output of the season. daughter Morgan Oregon ranked in the top 30 in the NCAA in 15 different statistical categories, including boasting the 12th-best rushing offense in the country rushing for 251.0 yards per game and the 18th-highest scoring offense averaging 36.0 points per game. On defense, the Florida State hired Florida native Willie Taggart to be its 10th full-time head football Ducks ranked 24th in the country in third-down defense allowing a .333 conversion coach on Dec. 5, 2017. Taggart is considered one of the best offensive minds in the percentage and 27th in fourth-down defense at .417. The defense had one of the best country and has already proven to be a relentless and effective recruiter. -

Miami Dolphins RB KARIM ABDUL-JABBAR Leads the NFL

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 25, 2006 NFL PRESS BOX NOTES – WEEK 8 LUCKY SEVENS: The CHICAGO BEARS and INDIANAPOLIS COLTS enter Week 8 with 6-0 records. With wins, they can reach NFL milestones. With a victory over visiting San Francisco Sunday, the Bears will join the Green Bay Packers and Minnesota Vikings as the only NFL teams to start a season 7-0 in four different years. The Colts, who started 7-0 for the first time in their history last year, can become the ninth team with two or more 7-0 starts. Following are the franchises with the most 7-0 starts in history: TEAM YEARS 7-0 STARTS Green Bay Packers 1929-31, 1962 4 Minnesota Vikings 1973, 1975, 1998, 2000 4 Chicago Bears 1934, 1942, 1985 3* Los Angeles/St. Louis Rams 1969, 1978, 1985 3 Four tied -- 2 Indianapolis Colts 2005 1* *Can attain 7-0 start this week Indianapolis this Sunday can become only the second team in history to start 7-0 in back-to-back seasons. The Green Bay Packers accomplished the feat with three consecutive 7-0 starts from 1929-31: TEAM YEARS CONSECUTIVE 7-0 STARTS Green Bay Packers 1929-31 3 Indianapolis Colts 2005 1* *Can reach consecutive 7-0 starts this week HOME SWEET HOME: Green Bay Packers quarterback BRETT FAVRE has thrown for 24,839 yards in 105 games at Lambeau Field. With 161 yards this Sunday against Arizona, Favre will join Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback JOHN ELWAY (27,889 yards at Denver’s Mile High Stadium) as the only players in the Super Bowl era (since 1966) to throw for 25,000 yards at a single venue. -

CLEVELAND BROWNS WEEKLY GAME RELEASE Regular Season Week 14, Game 13 Cleveland Browns (0-12) Vs

CLEVELAND BROWNS WEEKLY GAME RELEASE Regular Season Week 14, Game 13 Cleveland Browns (0-12) vs. Green Bay Packers (6-6) DATE: Sunday, Dec. 10, 2017 SITE: FirstEnergy Stadium KICKOFF: 1:00 p.m. CAPACITY: 67,431 SURFACE: Grass NOTABLE STORYLINES GAME INFORMATION The Browns return to FirstEnergy Stadium for the first Television of consecutive home games when they host the Green Bay FOX, Channel 8, Cleveland Packers at 1:00 p.m. on Sunday, Dec. 10. The Packers hold a Play-by-play: Thom Brennaman 12-7 advantage in the all-time regular season series, includ- Analyst: Chris Spielman ing a 6-4 mark in Cleveland. Sideline reporter: Jennifer Hale Last season, the Browns finished 31st in the NFL in both Radio total defense and rushing defense. Through 13 weeks this University Hospitals Cleveland Browns Radio Network year, the Browns rank 10th in total defense and sixth in rush- Flagship stations: 92.3 The Fan (WKRK-FM), ESPN 850 WKNR, ing defense. The highest the Browns have finished in run de- WNCX (98.5 FM) fense since 1999 was in 2013 when the team finished 18th. Play-by-play: Jim Donovan Analyst: Doug Dieken Since Week 8, the Browns are fourth in the league with a 4.95 rush average. Overall, the Browns are ninth in the NFL Sideline reporter: Nathan Zegura with a rushing average of 4.36 yards. In 2016, the Browns 2017 SCHEDULE finished second in the NFL with a 4.89 rushing average. PRESEASON (4-0) DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT NETWORK WR Josh Gordon, who was appearing in his first game THURS., AUG. -

1956 Topps Football Checklist

1956 Topps Football Checklist 1 John Carson SP 2 Gordon Soltau 3 Frank Varrichione 4 Eddie Bell 5 Alex Webster RC 6 Norm Van Brocklin 7 Packers Team 8 Lou Creekmur 9 Lou Groza 10 Tom Bienemann SP 11 George Blanda 12 Alan Ameche 13 Vic Janowicz SP 14 Dick Moegle 15 Fran Rogel 16 Harold Giancanelli 17 Emlen Tunnell 18 Tank Younger 19 Bill Howton 20 Jack Christiansen 21 Pete Brewster 22 Cardinals Team SP 23 Ed Brown 24 Joe Campanella 25 Leon Heath SP 26 49ers Team 27 Dick Flanagan 28 Chuck Bednarik 29 Kyle Rote 30 Les Richter 31 Howard Ferguson 32 Dorne Dibble 33 Ken Konz 34 Dave Mann SP 35 Rick Casares 36 Art Donovan 37 Chuck Drazenovich SP 38 Joe Arenas 39 Lynn Chandnois 40 Eagles Team 41 Roosevelt Brown RC 42 Tom Fears 43 Gary Knafelc Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Joe Schmidt RC 45 Browns Team 46 Len Teeuws RC, SP 47 Bill George RC 48 Colts Team 49 Eddie LeBaron SP 50 Hugh McElhenny 51 Ted Marchibroda 52 Adrian Burk 53 Frank Gifford 54 Charles Toogood 55 Tobin Rote 56 Bill Stits 57 Don Colo 58 Ollie Matson SP 59 Harlon Hill 60 Lenny Moore RC 61 Redskins Team SP 62 Billy Wilson 63 Steelers Team 64 Bob Pellegrini 65 Ken MacAfee 66 Will Sherman 67 Roger Zatkoff 68 Dave Middleton 69 Ray Renfro 70 Don Stonesifer SP 71 Stan Jones RC 72 Jim Mutscheller 73 Volney Peters SP 74 Leo Nomellini 75 Ray Mathews 76 Dick Bielski 77 Charley Conerly 78 Elroy Hirsch 79 Bill Forester RC 80 Jim Doran 81 Fred Morrison 82 Jack Simmons SP 83 Bill McColl 84 Bert Rechichar 85 Joe Scudero SP 86 Y.A. -

NFF SEPTEMBER 2010.Indd

NNFFFF JJoeoe TillerTiller ChapterChapter ooff NNorthwestorthwest IIndianandiana ““BuildingBuilding lleaderseaders tthroughhrough ffootball”ootball” VVolumeolume FFourour IIssuessue TThreehree SSeptembereptember 20102010 QB’s Take Center Stage at NFF Honors Dinner Former Purdue quarterbacks “stole the show” but a wide receiver-turned-quarterback walked off with the big trophy at the sixth annual NFF Honors Dinner on June 22nd at the Purdue Memorial Union. It was an evening of awards and celebration as Drew Brees, Len Dawson and Bob Griese, Purdue’s three Super Bowl Champion quarterbacks, appeared together for the fi rst time ever in West Lafayette to receive their Gold Medallions, while Mark Herrmann was honored as a 2010 selection for the College Foot- ball Hall of Fame. However, the big winner of the evening was West Lafayette High School standout Daniel Wodicka, who was named as Northwest Indiana’s Scholar Athlete of the Year, receiving a large trophy and scholarship as- sistance of more than $5,000. The event, co-hosted by the National Football Foundation’s Joe Tiller Chapter of Northwest Indiana and Purdue University’s Gimlet Leadership Honorary, drew a crowd of more than 750. In receiving the Gold Medallion, the QB trio earned the chapter’s highest award, having been awarded only once previously (to Dr. Martin Jischke upon his retirement as Purdue President in 2007). It is Above: Together for the fi rst time ever on campus at Purdue, the Boilermakers’ three Super Bowl Champion Quarterbacks, (left to right, Bob Gri- given only in special circumstances to honor highly ese, Drew Brees and Len Dawson), pose for pictures on stage at the Purdue Memorial Union Ballrooms just before receiving their Gold Medallions successful people who have achieved signifi cant ca- from the NFF’s Joe Tiller Chapter at the annual Honors Dinner in June (Photo by Brent Drinkut of Lafayette Journal & Courier). -

1952 Bowman Football (Large) Checkist

1952 Bowman Football (Large) Checkist 1 Norm Van Brocklin 2 Otto Graham 3 Doak Walker 4 Steve Owen 5 Frankie Albert 6 Laurie Niemi 7 Chuck Hunsinger 8 Ed Modzelewski 9 Joe Spencer 10 Chuck Bednarik 11 Barney Poole 12 Charley Trippi 13 Tom Fears 14 Paul Brown 15 Leon Hart 16 Frank Gifford 17 Y.A. Tittle 18 Charlie Justice 19 George Connor 20 Lynn Chandnois 21 Bill Howton 22 Kenneth Snyder 23 Gino Marchetti 24 John Karras 25 Tank Younger 26 Tommy Thompson 27 Bob Miller 28 Kyle Rote 29 Hugh McElhenny 30 Sammy Baugh 31 Jim Dooley 32 Ray Mathews 33 Fred Cone 34 Al Pollard 35 Brad Ecklund 36 John Lee Hancock 37 Elroy Hirsch 38 Keever Jankovich 39 Emlen Tunnell 40 Steve Dowden 41 Claude Hipps 42 Norm Standlee 43 Dick Todd Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Babe Parilli 45 Steve Van Buren 46 Art Donovan 47 Bill Fischer 48 George Halas 49 Jerrell Price 50 John Sandusky 51 Ray Beck 52 Jim Martin 53 Joe Bach 54 Glen Christian 55 Andy Davis 56 Tobin Rote 57 Wayne Millner 58 Zollie Toth 59 Jack Jennings 60 Bill McColl 61 Les Richter 62 Walt Michaels 63 Charley Conerly 64 Howard Hartley 65 Jerome Smith 66 James Clark 67 Dick Logan 68 Wayne Robinson 69 James Hammond 70 Gene Schroeder 71 Tex Coulter 72 John Schweder 73 Vitamin Smith 74 Joe Campanella 75 Joe Kuharich 76 Herman Clark 77 Dan Edwards 78 Bobby Layne 79 Bob Hoernschemeyer 80 Jack Carr Blount 81 John Kastan 82 Harry Minarik 83 Joe Perry 84 Ray Parker 85 Andy Robustelli 86 Dub Jones 87 Mal Cook 88 Billy Stone 89 George Taliaferro 90 Thomas Johnson Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© -

Curly Lambeau

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 6, No. 1 (1984) Curly Lambeau Just when most of the small town teams were disappearing, Lambeau had his Packers at the top of the NFL standings. He built a juggernaut that won league championships in 1929, ‘30, and ‘31. No team has ever topped that 3-straight record. Always, Lambeau’s teams emphasized the forward pass, using it as a main part of the offense when other teams treated it as a desperation tactic. In 1935, Don Hutson joined the pack, and – coupled with passers Arnie Herber and Cecil Isbell – he became the most devastating receiver the NFL had ever seen. Featuring Hutson, Lambeau’s Packers continued as a power into the 1940s, winning championships in 1936, ‘39, and ‘44. With six champions and 33 consecutive years as an NFL head coach, Lambeau was a shoo-in as a charter member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963. Today, the Green Bay Packers are the only remaining reminder that the National Football League was once studded with “small town” teams. Rock Island, Dayton, Canton and dozens of others competed against Chicago and New York. That little Green Bay survived where so many others failed was, more than anything else, due to the efforts of Earl “Curly” Lambeau. In 1919, when he should have been back at Notre Dame as George Gipp’s sophomore sub, Lambeau organized his frst Green Bay team and talked a local meat packer into sponsoring it. Two years later, Lambeau brought the Packers into the young NFL. Almost immediately, disaster struck! After only one season in the NFL, the Packers were found to have violated some league rules and the franchise was lifted. -

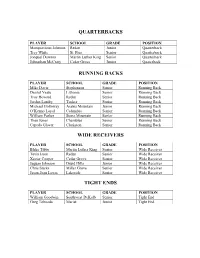

Quarterbacks Running Backs Wide Receivers Tight Ends

QUARTERBACKS PLAYER SCHOOL GRADE POSITION Monquavious Johnson Redan Junior Quarterback Trey White St. Pius Senior Quarterback Jonquel Dawson Martin Luther King Senior Quarterback Johnathan McCrary Cedar Grove Junior Quaterback RUNNING BACKS PLAYER SCHOOL GRADE POSITION Mike Davis Stephenson Senior Running Back Denzel Veale Lithonia Senior Running Back Troy Howard Redan Senior Running Back Jordan Landry Tucker Senior Running Back Michael Holloway Arabia Mountain Junior Running Back O’Kenno Loyal Columbia Senior Running Back William Parker Stone Mountain Senior Running Back Theo Jones Chamblee Senior Running Back Cepeda Glover Clarkston Senior Running Back WIDE RECEIVERS PLAYER SCHOOL GRADE POSITION Blake Tibbs Martin Luther King Senior Wide Receiver Tevin Isom Redan Senior Wide Receiver Xavier Cooper Cedar Grove Senior Wide Receiver Jaquan Johnson Druid Hills Junior Wide Receiver Chris Starks Miller Grove Senior Wide Receiver Jason-Jean Lewis Lakeside Senior Wide Receiver TIGHT ENDS PLAYER SCHOOL GRADE POSITION William Goodwin Southwest DeKalb Senior Tight End Greg Toboada Marist Junior Tight End OFFENSIVE LINEMEN PLAYER SCHOOL GRADE POSITION Jordan Head McNair Senior Offensive Lineman Najee Daniels Stephenson Senior Offensive Lineman Ken Crenshaw Tucker Senior Offensive Lineman Nick Brigham Marist Senior Offensive Lineman Jordan Barrs Marist Senior Offensive Lineman Michael Young Tucker Senior Offensive Lineman Brandon Greene Cedar Grove Senior Offensive Lineman Joseph Leavell Towers Senior Offensive Lineman Darien Foreman Dunwoody Senior -

Week 10 Game Release

WEEK 10 GAME RELEASE #BUFvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Rel ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med ia Rel ations Mik e Hel m - Manag er, Med ia Rel ations Imani Sube r - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinato r C hase Russe ll - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinator BUFFALO BILLS (7-2) VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS (5-3) State Farm Stadium | November 15, 2020 | 2:05 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2020 SCHEDULE Arizona will wrap up a nearly month-long three-game homestand and open Regular Season the second half of the season when it hosts the Buffalo Bills at State Farm Sta- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time dium this week. Sep. 13 @ San Francisco Levi's Stadium W, 24-20 Sep. 20 WASHINGTON State Farm Stadium W, 30-15 This week's matchup against the Bills (7-2) marks the fi rst of two games in a Sep. 27 DETROIT State Farm Stadium L, 23-26 five-day stretch against teams with a combined 13-4 record. Aer facing Buf- Oct. 4 @ Carolina Bank of America Stadium L 21-31 falo, Arizona plays at Seale (6-2) on Thursday Night Football in Week 11. Oct. 11 @ N.Y. Jets MetLife Stadium W, 30-10 Sunday's game marks just the 12th mee ng in a series that dates back to 1971. Oct. 19 @ Dallas+ AT&T Stadium W, 38-10 The two teams last met at Buffalo in Week 3 of the 2016 season. Arizona won Oct. 25 SEATTLE~ State Farm Stadium W, 37-34 (OT) three of the first four matchups between the teams but Buffalo holds a 7-4 - BYE- advantage in series aer having won six of the last seven games.