The Migration of WNBA Players to Overseas Basketball Teams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wake Forest Offense

JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2005 12 FOR BASKETBALL EVERYWHERE ENTHUSIASTS FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE ASSIST FABRIZIO FRATES SKIP PROSSER - DINO GAUDIO THE OFFENSIVE FUNDAMENTALS: the SPACING AND RHYTHM OF PLAY JONAS KAZLAUSKAS SCOUTING THE 2004 OLYMPIC GAMES WAKE FOREST paT ROSENOW THREE-PERSON OFFICIATING LARS NORDMALM OFFENSE CHALLENGES AT THE FIBA EUROBASKET 2003 TONY WARD REDUCING THE RISK OF RE-INJURY EDITORIAL Women’s basketball in africa is moving up The Athens Olympics were remarkable in many Women's sport in Africa needs further sup- ways. One moment in Olympic history deserves port on every level. It is not only the often special attention, especially as it almost got mentioned lack of financial resources and unnoticed during the many sensational perfor- facilities which makes it difficult to run proper mances during the Games - the women's classi- development programs. The traditional role of fication game for the 12th place. When the women in society and certain religious norms women's team from Nigeria celebrated a 68-64 can create further burdens. Saying that, it is win over Korea after coming back from a 18 - 30 obvious that the popularity of the game is margin midway through the second period, this high and Africa's basketball is full of talent. It marked the first ever African victory of a is our duty to encourage young female women's team in Olympic history. This is even players to play basketball and give them the the more remarkable, as it was only the 3rd opportunity to compete on the highest level. appearance of an African team in the Olympics against a world class team that was playing for The FIBA U19 Women’s World Championship Bronze just 4 years ago in Sydney. -

Results 19/12/2018 Page 1

Results 19/12/2018 Page 1 ALGERIA CUP CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 14:00 265 Remchi Eulma 0 : 0 1 : 0 18:00 6019 Gdansk Berlin RV 26 : 24 3 : 0 18:00 266 ES Setif Medea 1 : 0 1 : 0 18:00 6020 Karlovarsko Lube Civitanova 16 : 25 0 : 3 20:00 6021 Tours Perugia 19 : 25 1 : 3 ALPS LEAGUE 20:30 6022 Modena Kedzierzyn-Kozle 25 : 23 3 : 1 19:00 4061 Jesenice Ritten 1 : 1 7 : 4 CHAMPIONS LEAGUE WOMEN 19:15 4062 Olimpija Salzburg 2 1 : 0 4 : 2 19:30 4063 Eisbaren Val Pusteria 1 : 1 2 : 3 16:30 6023 Fenerbahce W Chemik Police W 25 : 12 3 : 0 18:00 6024 Minsk W Novara W 19 : 25 0 : 3 ARGENTINA LIGA A 19:00 6025 HPK W Eczacibasi W 11 : 25 0 : 3 1:00 3009 Ferro Estudiantes 39 : 40 86 : 67 19:00 6026 Stuttgart W Beziers W 25 : 16 3 : 0 AZERBAIJAN CUP CHINA CBA 13:00 267 Sabail Zira 1 : 1 2 : 3 12:35 3060 Guangzhou Zhej. Guangsha 50 : 47 88 : 102 16:00 268 SumQayit Neftci Baku 0 : 1 0 : 1 12:35 3061 Liaoning Qingdao 65 : 54 124 : 113 12:35 3062 Zhej. Chouzhou Guangdong 42 : 43 97 : 103 BELGIUM CUP CLUB WORLD CUP 20:00 103 Eupen Oostende 0 : 0 0 : 1 20:00 104 Mechelen Kortrijk 2 : 0 3 : 0 17:30 108 Kashima Real Madrid 0 : 1 1 : 3 20:45 105 St Gilloise Genk 1 : 0 2 : 2 CYPRUS CUP BOLIVIA 1 13:30 275 Paralimni Voroklinis 4 : 0 5 : 1 20:00 269 Destroyers U. -

Sherri Coale Of

she presides over one of the top teams in ColleGe sports, a proGram built for suCCess by teaChinG Championship behavior on and off the Court that’s why the sooners reload eaCh season with players who exCel athletiCally, aCademiCally, in the Community and beyond sherri Coale queenof the Court 114 SOONERSPORTS.COM 2009-10 Oklahoma Women’s Basketball Guide 115 Rare is the coach who embraces the balance of student and athlete like THE BIG DaNCE ACADEMIC SUCCESS Sherri Coale. Even fewer teams have had success while emphasizing Coale’s previous years were just stepping stones to national Coale, who was an Academic All-American and graduated summa cum the books on the same level as the balls. prominence as she guided Oklahoma to its first NCAA Final Four and laude from Oklahoma Christian, is a firm believer in succeeding in the national championship game during the 2001-02 season. The Sooners classroom as well as on the court. Under Coale’s guidance, her teams defeated Duke, 86-71, in the NCAA semifinals and lost to top-ranked have consistently produced some of the highest grade point averages The symmetry is a trademark of Coale’s program. and undefeated Connecticut, 82-70, in the title match. within the Athletics Department and posted a combined team GPA of 3.0 or better for a program record 23 of 26 semesters since 1996. She meticulously prepares her athletes to excel in the classroom By the conclusion of the greatest run in program history, OU had Four teams (1999, 2001, 2002, 2003) have been named to the Top and on the hardwood. -

Tv Pg 8 07-06.Indd

8 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, July 6, 2010 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening July 6, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC Wipeout Downfall Mind Games Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles The Good Wife Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC Losing It-Jillian America's Got Talent Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX Hell's Kitchen Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Dog Dog Dog Dog Dog Dog Dog the Bounty Hunter Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC The Negotiator Thunderheart Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather Last Lion of Liuwa I Shouldn't Be Alive Awesome Pawsome Last Lion of Liuwa Alive Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET The Wood Trey Songz The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show The Wood Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Housewives/NJ Housewives/NJ Griffin: My Life Double Exposure Griffin: My Life 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Extreme-Home Extreme-Home The Singing Bee The Bad News Bears 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY 29 CNBC 57 Disney South Pk S. -

Ponuda Za LIVE 24.1.2018. I DEO.Xlsx

powered by BetO2 kickoff_time event_id sport competition_name home_name away_name 2018-01-24 09:30:00 1058880 BASKETBALL Australia NBL Melbourne United Cairns Taipans 2018-01-24 09:30:00 1058879 BASKETBALL Philippine Cup Meralco Bolts KIA Picanto 2018-01-24 11:00:00 1058881 BASKETBALL South Korea KBL Seoul Knights Seoul Thunders 2018-01-24 11:00:00 1058882 BASKETBALL South Korea KBL Sonic Boom Dongbu Promy 2018-01-24 11:00:00 1058883 BASKETBALL South Korea WKBL Samsung Blue Minx Women S-Birds Women 2018-01-24 12:00:00 1058884 BASKETBALL Philippine Cup Globalport San Miguel Beermen 2018-01-24 12:35:00 1058885 BASKETBALL China CBA Shanxi Zhongyu Shenzhen 2018-01-24 12:35:00 1058886 BASKETBALL China CBA Fujian Lightning Zhejiang Chouzhou 2018-01-24 12:35:00 1058887 BASKETBALL China CBA Beijing Dragons Liaoning 2018-01-24 12:35:00 1058888 BASKETBALL China CBA Tianjin Guangzhou 2018-01-24 12:35:00 1058889 BASKETBALL China CBA Zhejiang Guangsha Shanghai 2018-01-24 13:00:00 1058890 BASKETBALL Asia ABL Eastern Long Lions CLS Knights Surabaya 2018-01-24 13:00:00 1058891 BASKETBALL Asia ABL Mono Vampire Formosa Dreamers 2018-01-24 13:30:00 1058892 BASKETBALL Champions League Enisey Krasnoyarsk Hapoel Holon 2018-01-24 14:00:00 1059066 BASKETBALL Turkey Federation Cup Antalyaspor Bakirkoy 2018-01-24 15:00:00 1058893 BASKETBALL Euroleague Women Nadezhda Women Perfumerias Avenida W 2018-01-24 15:30:00 1059067 BASKETBALL Qatar QBL Al Sadd Al Shamal 2018-01-24 16:00:00 1059068 BASKETBALL ABA League 2 Ohrid Zrinjski 2018-01-24 16:00:00 1058894 BASKETBALL -

NORTHWESTERN BUILDING the Cornerstone of Retail & Business • 201 South Denver Avenue • Downtown Tulsa

NORTHWESTERN BUILDING The Cornerstone of Retail & Business • 201 South Denver Avenue • Downtown Tulsa www.paine-associates.com OVERVIEW • New Class A Office Space Available (4100 SF to 22,000 SF) • Front Door to BOK Center • Retail/Restaurant Space Available (4100 SF) • Strongest Daytime Population in Tulsa Market (32,500 Daily) • Leased Office Space (324,326 SF) • Convenient Access • 1,000 Employees On-Site • 24-Hour Security and On-Site Management Team • 1,152 Weekend Parking Spaces Available • Adjacent to Home of Cimarex Energy • Ample Street and City Parking Garage Available • Home of Northwestern Mutual www.paine-associates.com www.paine-associates.com 2nd Street AVAILABLE AVAILABLE Denver Avenue Denver Cheyenne Avenue Northwestern Building - Lease Plan Second Floor www.paine-associates.com 2nd Street AVAILABLE AVAILABLE Denver Avenue Denver Cheyenne Avenue Northwestern Building - Lease Plan Third Floor www.paine-associates.com Downtown Tulsa is the Place to Be Northwestern Building Located in the BOK Center Entertainment District, the $100+ million mixed-use development is at the front door of the iconic, world-class BOK Center. The area features office, residential, hotel, retail and event space. Northwestern Building offers a unique tenant opportunity to locate within Downtown Tulsa’s newest and largest private development. Bustling Downtown Tulsa In the past decade nearly $500 million has been invested in downtown Tulsa. The 18,000 residential population within a one mile radius combined with the thousands of visitors that attend the 750+ annual events, the city’s urban core draws consumers from the entire Tulsa MSA and beyond. An additional $350 million is being invested in projects in Downtown Tulsa. -

Difference-Based Analysis of the Impact of Observed Game Parameters on the Final Score at the FIBA Eurobasket Women 2019

Original Article Difference-based analysis of the impact of observed game parameters on the final score at the FIBA Eurobasket Women 2019 SLOBODAN SIMOVIĆ1 , JASMIN KOMIĆ2, BOJAN GUZINA1, ZORAN PAJIĆ3, TAMARA KARALIĆ1, GORAN PAŠIĆ1 1Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, University of Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2Faculty of Economy, University of Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina 3Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, University of Belgrade, Serbia ABSTRACT Evaluation in women's basketball is keeping up with developments in evaluation in men’s basketball, and although the number of studies in women's basketball has seen a positive trend in the past decade, it is still at a low level. This paper observed 38 games and sixteen variables of standard efficiency during the FIBA EuroBasket Women 2019. Two regression models were obtained, a set of relative percentage and relative rating variables, which are used in the NBA league, where the dependent variable was the number of points scored. The obtained results show that in the first model, the difference between winning and losing teams was made by three variables: true shooting percentage, turnover percentage of inefficiency and efficiency percentage of defensive rebounds, which explain 97.3%, while for the second model, the distinguishing variables was offensive efficiency, explaining for 96.1% of the observed phenomenon. There is a continuity of the obtained results with the previous championship, played in 2017. Of all the technical elements of basketball, it is still the shots made, assists and defensive rebounds that have the most significant impact on the final score in European women’s basketball. -

Eurocup Women 2020-2021

Regulations governing the EuroCup Women 2020-2021 As adopted by FIBA Europe in 2020 Regulations governing the EUROCUP Women 2020-2021 Page 1 Table of Contents I. ADMINISTRATION 2 1. Competition 2 2. Trophy 2 3. Communication 2 4. Workshop for Statisticians 2 II. RIGHT TO PARTICIPATE IN THE 2020-2021 SEASON 3 5. National Federations 3 6. Clubs 3 7. Evaluation of the National Federations for the 2020/2021 season 3 8. Registration of Clubs 4 III. CALENDAR 5 9. General Calendar EuroCup Women (ECW) 5 10. Draw 5 IV. SYSTEM OF COMPETITION 6 11. General Principles 6 12. Qualifiers 6 13. Regular Season 6 14. Final Round - Play-Offs 7 15. Play-Off Round 1 7 16. Round of 16 8 17. Round of 8 & Quarter-Finals 8 18. Semi-Finals 9 19. Finals 9 V. PLAYERS 10 20. Provisions concerning the eligibility of players: 10 21. Licences 10 22. Preliminary Roster 10 23. Procedure for changes 11 VI. FINALs 12 VII. FINANCES 12 24. General Financial Provisions 12 25. Game Videos Online Platform 12 VIII. GENERAL NOTE 13 IX. SUMMARY OF DEADLINES 14 X. ANNEX I: COURT LAYOUT OF THE EUROCUP WOMEN (ECW) 15 26. FIBA Logo & EuroCup Women Logo 16 27. Standards 16 XI. MEDIA AND BROADCASTING 17 28. Preamble 17 29. Media and Broadcasting Rights 17 30. Rights to Images 17 31. TV and Streaming Obligations and Operations 17 32. Team Press Officers 18 33. Venue Media Operations 18 34. Social Media 19 35. Team Media Availability 19 36. Pre-Season and Game Day Obligations 19 Regulations governing the EuroCup Women 2020-2021 Regulations governing the EUROCUP Women 2020-2021 Page 2 I. -

Sportonsocial 2018 1 INTRODUCTION

#SportOnSocial 2018 1 INTRODUCTION 2 RANKINGS TABLE 3 HEADLINES 4 CHANNEL SUMMARIES A) FACEBOOK CONTENTS B) INSTAGRAM C) TWITTER D) YOUTUBE 5 METHODOLOGY 6 ABOUT REDTORCH INTRODUCTION #SportOnSocial INTRODUCTION Welcome to the second edition of #SportOnSocial. This annual report by REDTORCH analyses the presence and performance of 35 IOC- recognised International Sport Federations (IFs) on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube. The report includes links to examples of high-performing content that can be viewed by clicking on words in red. Which sports were the highest climbers in our Rankings Table? How did IFs perform at INTRODUCTION PyeongChang 2018? What was the impact of their own World Championships? Who was crowned this year’s best on social? We hope you find the report interesting and informative! The REDTORCH team. 4 RANKINGS TABLE SOCIAL MEDIA RANKINGS TABLE #SportOnSocial Overall International Channel Rank Overall International Channel Rank Rank* Federation Rank* Federation 1 +1 WR: World Rugby 1 5 7 1 19 +1 IWF: International Weightlifting Federation 13 24 27 13 2 +8 ITTF: International Table Tennis Federation 2 4 10 2 20 -1 FIE: International Fencing Federation 22 14 22 22 3 – 0 FIBA: International Basketball Federation 5 1 2 18 21 -6 IBU: International Biathlon Union 23 11 33 17 4 +7 UWW: United World Wrestling 3 2 11 9 22 +10 WCF: World Curling Federation 16 25 12 25 5 +3 FIVB: International Volleyball Federation 7 8 6 10 23 – 0 IBSF: International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation 17 15 19 30 6 +3 IAAF: International -

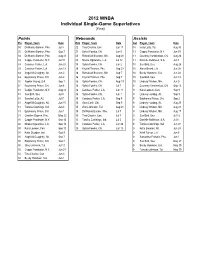

2012 WNBA Individual Single-Game Superlatives (Final)

2012 WNBA Individual Single-Game Superlatives (Final) Points Rebounds Assists Pts Player, Team Date Reb Player, Team Date Ast Player, Team Date 38 DeWanna Bonner, Pho. Jul 3 22 Tina Charles, Con. Jun 17 14 Ivory Latta, Tul. Aug 30 35 DeWanna Bonner, Pho. Sep 7 21 Sylvia Fowles, Chi. Jun 8 13 Cappie Pondexter, N.Y. Jun 19 34 DeWanna Bonner, Pho. Aug 23 20 Rebekkah Brunson, Min. Aug 28 11 Courtney Vandersloot, Chi. Aug 26 33 Cappie Pondexter, N.Y. Jul 10 20 Nneka Ogwumike, L.A. Jul 12 11 Danielle Robinson, S.A. Jun 1 33 Candace Parker, L.A. Jun 20 19 Sylvia Fowles, Chi. Jun 2 10 Sue Bird, Sea. Aug 26 33 Candace Parker, L.A. Jun 13 18 Krystal Thomas, Pho. Sep 23 10 Alana Beard, L.A. Jun 28 33 Angel McCoughtry, Atl. Jun 2 18 Rebekkah Brunson, Min. Sep 7 10 Becky Hammon, S.A. Jun 24 33 Epiphanny Prince, Chi. Jun 2 16 Krystal Thomas, Pho. Sep 7 10 Sue Bird, Sea. Jun 13 32 Sophia Young, S.A. Sep 1 16 Sylvia Fowles, Chi. Aug 19 10 Lindsay Whalen, Min. Jun 9 32 Epiphanny Prince, Chi. Jun 8 16 Sylvia Fowles, Chi. Jul 7 9 Courtney Vandersloot, Chi. Sep 13 31 Cappie Pondexter, N.Y. Aug 23 16 Candace Parker, L.A. Jun 13 9 Kara Lawson, Con. Sep 9 31 Sue Bird, Sea. Jul 8 16 Sylvia Fowles, Chi. Jun 1 9 Lindsey Harding, Atl. Sep 9 31 Sancho Lyttle, Atl. Jul 7 15 Candace Parker, L.A. -

Ziad Joseph RAHAL Sport Mondial Et Culture Moyen-Orientale, Une

UNIVERSITÉ LILLE II U.F.R. S.T.A.P.S. 9, rue de l'Université 59790 -Ronchin THÈSE pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE LILLE II, en Sciences et Techniques des Activités Physiques et Sportives Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 13 décembre 2017 par Ziad Joseph RAHAL Sport mondial et culture moyen-orientale, une interaction dialectique récente. Le cas du Liban. Directeur de thèse Professeur Claude SOBRY Univ. Lille, EA 7369 Membres du Jury URePSSS -Unité de Recherche Pluridiscipli- Mme Sorina CERNAIANU, Université de Craiova (Roumanie) naire Sport Santé Société, Professeur Patrick BOUCHET, Université de Dijon (rapporteur) F-59000 Professeur Michel RASPAUD, Université de Grenoble Alpes (rapporteur) M. Nadim NASSIF, Université Notre-Dame, Beyrouth (Liban) Professeur Fabien WILLE, Université Lille II (Président) Professeur Claude SOBRY, Université Lille II (Directeur de thèse) UNIVERSITÉ LILLE II U.F.R. S.T.A.P.S. 9, rue de l'Université 59790 -Ronchin THÈSE pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE LILLE II, en Sciences et Techniques des Activités Physiques et Sportives Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 13 décembre 2017 par Ziad Joseph RAHAL Sport mondial et culture moyen-orientale, une interaction dialectique récente. Le cas du Liban. Directeur de thèse Professeur Claude SOBRY Univ. Lille, EA 7369 Membres du Jury : URePSSS -Unité de Recherche Pluridiscipli- Mme Sorina CERNAIANU, Université de Craiova (Roumanie) naire Sport Santé Société, Professeur Patrick BOUCHET, Université de Dijon (rapporteur) F-59000 Professeur Michel RASPAUD, Université de Grenoble Alpes (rapporteur) M. Nadim NASSIF, Université Notre-Dame, Beyrouth (Liban) Professeur Fabien WILLE, Université Lille 2 (Président) Professeur Claude SOBRY, Université Lille 2 (Directeur de thèse) Remerciements : Au terme de ce parcours universitaire qui aboutit aujourd’hui à la soutenance de cette thèse, il me revient d’exprimer mes plus sincères remerciements à toutes celles et ceux sans qui, ce travail n’aurait pas pu voir le jour. -

Fitting the Opponent 12 02 - 05.08 FIBA Diamond Ball for by Ettore Messina and Lele Molin FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE Women in Haining, P.R

july / august 2008 / august july 33 FOR basketball enthusiasts everywhere enthusiasts basketball FOR FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE FIBA ASSIST assist Pianigiani-Banchi The high Ettore Messina pick-and-roll Pat Sullivan Lele Molin The “point zone” Jim Cervo Understanding Fitting 3-person mechanics Rich Dalatri Band exercises the opponent tables of contents 2008-09 FIBA CALENDAR COACHES FUNDAMENTALS AND YOUTH BASKETBALL JULY 2008 Zone Offense Principles 4 14 - 20.07 FIBA Olympic Qualifying Tournament for Men in by Don Showalter Athens, Greece 17 -21.07 Centrobasket Championship for Testing and Evaluating the Motor Potential 10 Women in Morovis, Puerto of Young Basketball Players Rico by Frane Erculj 29.07 - 01.08 FIBA Diamond Ball for Men in Nanjing, P.R. of China OFFENSE AUGUST 2008 Fitting the Opponent 12 02 - 05.08 FIBA Diamond Ball for by Ettore Messina and Lele Molin FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE Women in Haining, P.R. IS A PUBLICATION OF FIBA of China International Basketball Federation Posting Up the Perimeter Players 16 51 – 53, Avenue Louis Casaï 09 - 24.08 Olympic Basketball CH-1216 Cointrin/Geneva Switzerland Tournaments for Men by Kestutis Kemzura Tel. +41-22-545.0000, Fax +41-22-545.0099 and Women in Beijing, www.fiba.com / e-mail: [email protected] P.R. of China 18 27 - 31.08 Centrobasket The High Pick and Roll IN COLLABORATION WITH Giganti del Basket, Championship for Men in by Simone Pianigiani and Luca Banchi Cantelli Editore, Italy Cancun, Mexico PARTNER WABC (World Association of Basketball SEPTEMBER 2008 DEFENSE Coaches), Dusan Ivkovic President 06 - 17.09 ParaOlympic Games, The "Point Zone" 24 Wheelchair Basketball by Pat Sullivan Tournaments in Beijing, Editor-in-Chief P.R.