Collated Responses to 'Nassau Documents' from Around the Communion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LITURGICAL INSTRUCTIONS When the BISHOP CELEBRATES MASS GENERAL LITURGICAL INSTRUCTIONS for EMCEES Before Mass: 1

DIOCESE OF BATON ROUGE LITURGICAL INSTRUCTIONS when the BISHOP CELEBRATES MASS GENERAL LITURGICAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR EMCEES Before Mass: 1. The pastor or his designate is responsible for setting up for the ceremony. The bishop must approve any changes from what is listed below. 2. Be certain all is prepared in the church, making sure all needed vessels and books are in place and correctly marked. Prepare sufficient hosts and wine so that the entire congregation will be able to receive Holy Communion consecrated at that Mass. The lectionary is placed on the ambo open to the first reading. Check the microphones and batteries! 3. Seats for concelebrating priests and servers are not to flank the bishop’s presidential chair, but instead be off to the side; the bishop’s presidential chair is to be arranged by itself. (Exception: one deacon, if present, sits on the bishop’s right; a second deacon if present may sit to the bishop’s left.) 4. The altar should be bare at the beginning of the celebration (excepting only the required altar cloth, and candles, which may be placed upon the altar). Corporals, purificators, books and other items are not placed on the altar until the Prepa- ration of the Gifts. 5. If incense is used, refer to note no. 2 in the “Liturgical Instructions for the Sacrament of Confirmation.” 6. Getting started on time is very important. Sometimes it is necessary to be assertive in order to get people moving. 7. Give the following directions to all concelebrating priests: a. During the Eucharistic Prayer, stand well behind and to the left and to the right of the bishop. -

Yes to Communion – No to Covenant

No Anglican Covenant Coalition Anglicans for Comprehensive Unity noanglicancovenant.org NEWS RELEASE MARCH 13, 2012 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE YES TO COMMUNION – NO TO COVENANT LONDON – With more than half of English dioceses having voted, leaders of the No Anglican Covenant Coalition are cautiously optimistic. To date, a significant majority of dioceses have rejected the proposed Anglican Covenant. Coalition Moderator, the Revd Dr Lesley Crawley, welcomes the introduction of following motions at several recent synods emphasizing support for the Anglican Communion. Four dioceses have already passed following motions (Bath and Wells; Chelmsford; Worcester; Southwark) and a further six have following motions on the agenda (St Albans; Chester; Oxford; Guilford; Exeter; London). “The more widely the Covenant is read and discussed, the more likely people are to see it as a deeply flawed approach to the challenges of the Anglican Communion in the 21st century,” said Crawley. “The introduction of following motions in several dioceses has emphasized what has been our position from the beginning: we oppose the Covenant because we love the Anglican Communion.” “The proposed Covenant envisages the possibility that Provinces of the Communion may be barred from representing Anglicanism on certain councils and commissions with the clear implication that they are no longer sufficiently Anglican,” said Coalition Patron Bishop John Saxbee. “It is precisely this dimension of the Covenant which renders the Covenant itself un-Anglican.” “Some have argued that the Covenant is necessary for ecumenical relations to indicate how Anglicans understand catholicity, even though this is already laid out in the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral and the Declaration of Assent,” according to Coalition Patron Bishop Peter Selby. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

The Search for Real Christianity: Nineteenth-Century England for a Number of Lessons, We Have Been Looking at Church History In

Reformation & Modern Church History Lesson 31, Page 1 The Search for Real Christianity: Nineteenth-Century England For a number of lessons, we have been looking at church history in America. Now we go back to the continent of Europe and to England for this lesson. The prayer I will open with comes from the prayer book of the Church of England, from what is called “The Lesser Peace and Fast.” One of the celebration days on the church calendar of the Church of England has to do with a man whose name will come up in today’s lesson, Charles Simeon. On that particular day in the prayer book, this prayer relates to the life and testimony of Charles Simeon. So, as we begin this lesson, I would like for us to use this prayer, thanking the Lord for Simeon and other faithful ministers whom we will be talking about during this time. Let us pray. O loving Lord, we know that all things are ordered by Thine unswerving wisdom and unbounded love. Grant us in all things to see Thy hand, that following the example of Charles Simeon, we may walk with Christ with all simplicity and serve Thee with a quiet and contented mind through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with Thee and with the Holy Spirit—one God forever and ever. Amen. As we think about the history of Christianity in England in the nineteenth century, we begin, of course, with the Church of England, and we begin with the Broad Church. In one of Henry Fielding’s novels, he has a character who says this, “When I mention religion, I mean the Christian religion and not only the Christian religion but the Protestant religion and not only the Protestant religion but the Church of England.” And that was probably the attitude of many people who were members of the church in England in the nineteenth century, particularly members of what was called the Broad Church or adherents to the Broad Church philosophy. -

2.2 the MONARCHY Republican Sentiment Among New Zealand Voters, Highlighting the Social Variables of Age, Gender, Education

2.2 THE MONARCHY Noel Cox and Raymond Miller A maturing sense of nationhood has caused some to question the continuing relevance of the monarchy in New Zealand. However, it was not until the then prime minister personally endorsed the idea of a republic in 1994 that the issue aroused any significant public interest or debate. Drawing on the campaign for a republic in Australia, Jim Bolger proposed a referendum in New Zealand and suggested that the turn of the century was an appropriate time symbolically for this country to break its remaining constitutional ties with Britain. Far from underestimating the difficulty of his task, he readily conceded that 'I have picked no sentiment in New Zealand that New Zealanders would want to declare themselves a republic'. 1 This view was reinforced by national survey and public opinion poll data, all of which showed strong public support for the monarchy. Nor has the restrained advocacy for a republic from Helen Clark, prime minister from 1999, done much to change this. Public sentiment notwithstanding, a number of commentators have speculated that a New Zealand republic is inevitable and that any move in that direction by Australia would have a dramatic influence on public opinion in New Zealand. Australia's decision in a national referendum in 1999 to retain the monarchy raises the question of what effect, if any, that decision had on opinion on this side of the Tasman. In this chapter we will discuss the nature of the monarchy in New Zealand, focusing on the changing role and influence of the Queen's representative, the governor-general, together with an examination of some of the factors that might have an influence on New Zealand becoming a republic. -

From Wycliffe to Japan

WYCLIFFE COLLEGE • WINTER 2012 IN THIS ISSUE • Report from the Office of the From Wycliffe to Japan Registrar and Admissions BY STAFF WITH ADDITIONAL INFORMATION FROM JILL ROBINSON page 3 • A Student’s Journey to Ramallah OHN CoopeR Robinson graduated from Wycliffe page 4 JCollege in 1886 and went to Japan in 1888 as the first • Chinese Christianity Canadian sponsored Anglican missionary. He was also an obsessed “Out of the Ashes” photographer and, in the estimation of photography scholars, page 8 a very good one too. He had the great good fortune to be in a • Alumni/ae News unique place at a unique time and documented the transition of page 13 Meiji-Taisho Japan from feudal society to the western industrial INSIGHT super-power it would become in slightly over one generation. As far as is known, the collection is the only comprehensive photo- The Wycliffe College Newsletter John Cooper Robinson for Alumni/ae and Friends graphic record of this extraordinary period. In the words of the December 2012 No. 74 late Marius Jansen, former Head of the Department of East Asian ISSN 1192-2761 Affairs at Princeton, “these (photos) lay to rest many of the questions East Asian scholars have debated EDITORIAL BOARD for years.” Recently, a small sample of his photographs were published and when his great-granddaughter Karen Baker-Bigauskas Jill Robinson contacted us to offer a copy of the book, we were indeed interested in meeting. Rob Henderson Angela Mazza Bonnie Kung Thomas Power The photos we viewed had much to say. It is clear why so many institutions including the National CONTRIBUTORS Library and Archives have expressed enthusiasm about these more than three thousand images. -

Crosier Generalate Canons Regular of the Order of the Holy Cross Via Del Velabro 19, 00186 Rome, Italy

Crosier Generalate Canons Regular of the Order of the Holy Cross Via del Velabro 19, 00186 Rome, Italy Letter of the Master General to present the Crosier Priesthood Profile A common question often asked by people is: “What is the distinctiveness of a Crosier priest as compared to other religious and secular priests?” It is a reasonable question. It flows from what people sense as the fundamental commonality shared among all religious and secular priests: sharing in Christ’s priesthood which then also demands a commitment to serving God and the People of God. There are differences and distinctions among priestly charisms exercised in the Church even all are founded on the one priesthood of Jesus Christ. Crosiers consequently should understand that religious priesthood (the identity as ordained ministers) is to be lived out in concert with the vows and the common life. We need to realize that the charism of the Order must be understood, internalized, and externalized in daily life. The values of our Crosier charism characterize our distinct way of being and serving within the concert of charisms in the Church and the Order of Presbyters. Our Crosier priesthood in an Order of Canons Regular should be colored by the elements of our Crosier religious life identity. This includes our lifelong commitment to fraternal community life, dedication to common liturgical prayer, and pastoral ministries that are energized by our religious life. For this reason, Crosiers commit to living out these living elements of our tradition; a heritage emphasized beginning in the years of novitiate and formation (see: Cons. -

The Interface Between Aboriginal People and Maori/Pacific Islander Migrants to Australia

CUZZIE BROS: THE INTERFACE BETWEEN ABORIGINAL PEOPLE AND MAORI/PACIFIC ISLANDER MIGRANTS TO AUSTRALIA By James Rimumutu George BA (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Newcastle March 2014 i This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: Date: ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors, Professor John Maynard and Emeritus Professor John Ramsland for their input on this thesis. Professor Maynard in particular has been an inspiring source of support throughout this process. I would also like to give my thanks to the Wollotuka Institute of Indigenous Studies. It has been so important to have an Indigenous space in which to work. My special thanks to Dr Lena Rodriguez for having faith in me to finish this thesis and also for her practical support. For my daughter, Mereana Tapuni Rei – Wahine Toa – go girl. I also want to thank all my brothers and sisters (you know who you are). Without you guys life would not have been so interesting growing up. This thesis is dedicated to our Mum and Dad who always had an open door and taught us to be generous and to share whatever we have. -

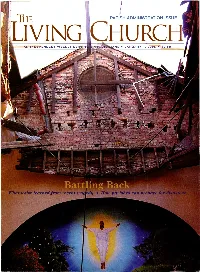

PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1Llving CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I

1 , THE PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1llVING CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I, ENDURE ... EXPLORE YOUR BEST ACTIVE LIVING OPTIONS AT WESTMINSTER COMMUNITIES OF FLORIDA! 0 iscover active retirement living at its finest. Cf oMEAND STAY Share a healthy lifestyle with wonderful neighbors on THREE DAYS AND TWO any of our ten distinctive sun-splashed campuses - NIGHTS ON US!* each with a strong faith-based heritage. Experience urban excitement, ATTENTION:Episcopalian ministers, missionaries, waterfront elegance, or wooded Christian educators, their spouses or surviving spouses! serenity at a Westminster You may be eligible for significant entrance fee community - and let us assistance through the Honorable Service Grant impress you with our signature Program of our Westminster Retirement Communities LegendaryService TM. Foundation. Call program coordinator, Donna Smaage, today at (800) 948-1881 for details. *Transportation not included. Westminster Communities of Florida www.WestminsterRetirement.com Comefor the Lifestyle.Stay for a Lifetime.T M 80 West Lucerne Circle • Orlando, FL 32801 • 800.948.1881 The objective of THELIVI N G CHURCH magazine is to build up the body of Christ, by describing how God is moving in his Church ; by reporting news of the Church in an unbiased manner; and by presenting diverse points of view. THIS WEEK Features 16 2005 in Review: The Church Begins to Take New Shape 20 Resilient People Coas1:alChurches in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina BYHEATHER F NEWfON 22 Prepare for the Unexpected Parish sUIVivalcan hinge on proper planning BYHOWARD IDNTERTHUER Opinion 24 Editor's Column Variety and Vitality 25 Editorials The Holy Name 26 Reader's Viewpoint Honor the Body BYJONATHAN B . -

Welsh Disestablishment: 'A Blessing in Disguise'

Welsh disestablishment: ‘A blessing in disguise’. David W. Jones The history of the protracted campaign to achieve Welsh disestablishment was to be characterised by a litany of broken pledges and frustrated attempts. It was also an exemplar of the ‘democratic deficit’ which has haunted Welsh politics. As Sir Henry Lewis1 declared in 1914: ‘The demand for disestablishment is a symptom of the times. It is the democracy that asks for it, not the Nonconformists. The demand is national, not denominational’.2 The Welsh Church Act in 1914 represented the outcome of the final, desperate scramble to cross the legislative line, oozing political compromise and equivocation in its wake. Even then, it would not have taken place without the fortuitous occurrence of constitutional change created by the Parliament Act 1911. This removed the obstacle of veto by the House of Lords, but still allowed for statutory delay. Lord Rosebery, the prime minister, had warned a Liberal meeting in Cardiff in 1895 that the Welsh demand for disestablishment faced a harsh democratic reality, in that: ‘it is hard for the representatives of the other 37 millions of population which are comprised in the United Kingdom to give first and the foremost place to a measure which affects only a million and a half’.3 But in case his audience were insufficiently disheartened by his homily, he added that there was: ‘another and more permanent barrier which opposes itself to your wishes in respect to Welsh Disestablishment’, being the intransigence of the House of Lords.4 The legislative delay which the Lords could invoke meant that the Welsh Church Bill was introduced to parliament on 23 April 1912, but it was not to be enacted until 18 September 1914. -

Anglican Catholicism Send This Fonn Or Call Us Toll Free at 1-800-211-2771

THE [IVING CHURCH AN INDEPENDENT WEEKLY SUPPORTING CATHOLIC ANGLICANISM • NOVEMBER 8 , 2009 • $2.50 Rome Welcomes Anglican Catholicism Send this fonn or call us toll free at 1-800-211-2771. I wish to give (check appropriate box and fill in) : My name: D ONE one-year gift subscription for $38.00 (reg. gift sub. $40.00) D TWO one-year gift subscriptions for $37 .00 each Name ------------''---------- Addres s __ _ __________ _ _____ _ ($37.00 X 2 = $74.00) THREE OR MORE one-year gift subscriptions for $36.00 each City/State/Zip ____ _ __________ _ _ _ D ($36.00 X __ = $._ _ ____, Phone _ __ ________________ _ Please check one: 0 One-time gift O Send renewal to me Email ____ _ ______________ _ Makechecks payable to : My gift is for: The living Church P.O.Box 514036 Milwaukee, WI 53203-3436 31.rec"-------------- Foo,ign postage extra First class rar,s available I VISA I~ ~ .,__· _c.· __________ _ D Please charge my credit card $ ____ _ ~ City/Stite/Zip __ _ _______ _ NOTE: PLEASE Fll.L IN CREDIT CARD BILLINGINFORMATION BELOW IF DIFFERENT FROM ADDRESS ABOVE. Phone Billing Address ________ _ _ _ _ _ ____ _ Bi.Bing City Please start this gift subscription O Dec. 20, 2009 Credit Card # _ _ _ _ _ __ _ _ Exp. Sign gift card _ _________ _ THELIVING CHURCH magazine is published by the Living Church Foundation, LIVINGCHURCH Inc. The historic mission of the Living Church Foundation is to promote and M independent weekly serving Episcopalians since1878 support Catholic Anglicanism within the Episcopal Church. -

Missional Imperatives Archbishop Gomez

Missional Imperatives for the Anglican Church in the Caribbean The Most Rev. Drexel Gomez, Retired Archbishop of the West Indies Introduction The Church in The Province Of The West Indies (CPWI) is a member church of the Anglican Communion (AC). The AC is comprised of thirty-eight (38) member churches throughout the global community, and constitutes the third largest grouping of Christians in the world, after the Roman Catholic Communion, and the Orthodox Churches. The AC membership is ordinarily defined by churches being in full communion with the See of Canterbury, and which recognize the Archbishop of Canterbury as Primus Inter Pares (Chief Among Equals) amongst the Primates of the member churches. The commitment to the legacy of Apostolic Tradition, Succession, and Progression serves to undergird not only the characteristics of Anglicanism itself, provides the ongoing allegiance to some Missional Imperatives, driven and sustained by God’s enlivening Spirit. Anglican Characteristics Anglicanism has always been characterized by three strands of Christian emphases – Catholic, Reformed, and Evangelical. Within recent times, the AC has attempted to adopt specific methods of accentuating its Evangelical character for example by designating a Decade of Evangelism. More recently, the AC has sought to provide for itself a new matrix for integrating its culture of worship, work, and witness in keeping with its Gospel proclamation and teaching. The AC more recently determined that there should also be a clear delineation of some Marks of Mission. It agreed eventually on what it has termed the Five Marks of Mission. They are: (1) To proclaim the Good News of the Kingdom; (2) To teach, baptize and nurture new believers; (3) To respond to human need by loving service; (4) To seek to transform unjust structures in society to challenge violence of every kind and to pursue peace and reconciliation; (5) To strive to safeguard the integrity of creation, and sustain and renew the life of the earth.