Final Report of Working Party Reviewing the Clergy Discipline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

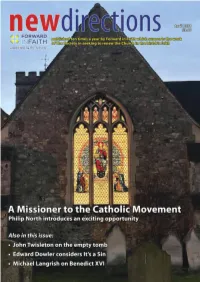

The Empty Tomb

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Ecclesiastical Law Journal

Ecclesiastical Law Journal Volume 21 2019 PUBLISHED BY CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS ON BEHALF OF THE ECCLESIASTICAL LAW SOCIETY Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.14, on 26 Sep 2021 at 04:48:54, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956618X19000930 Consolidated List of Contents for Volume 21 EDITORIAL Will Adam 1, 135, 265 ARTICLES Archdeacons and the Law Jane Steen 2 The Convocations of Canterbury and York Sion Hughes Carew 19 Richard Hooker: Invention and Re-invention Diarmaid MacCulloch 137 The Church of England and Same-Sex Marriage: Beyond a Rights-Based Analysis Charlotte Smith 153 The Constitutional Implications of the Survival of the Diocese of Sodor and Man Peter W Edge 179 Advowsons and Private Patronage Teresa Sutton 267 Women’s Ordination in the Church of England: Conscience, Change and Law Jane Steen 289 Self-Government Without Disestablishment: From the Enabling Act to the General Synod Colin Podmore 312 Establishment: Some Theological Considerations Malcolm Brown 329 COMMENT Lachiri v Belgium and Bans on Wearing Islamic Dress in the Courtroom: An Emerging Trend Kaushik Paul 48 Gospel and Order in the Rule of St Benedict Norman Boakes 196 The Council of Europe and Sharia: An Unsatisfactory Resolution? Russell Sandberg and Frank Cranmer 203 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.14, on 26 Sep 2021 at 04:48:54, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. -

Th E Year in Review

2012 – 2013 T HE Y EAR IN R EVIEW C AMBRIDGE T HEOLOGICAL F EDERATION Contents Page Foreword from the Bishop of Ely 3 Principal’s Welcome 4 Highlights of the Year 7 The Year in Pictures 7 Cambridge Theological Federation 40th anniversary 8 Mission, Placements and Exchanges: 10 • Easter Mission 10 USA Exchanges 11 • Yale Divinity School 11 • Sewanee: The University of the South 15 • Hong Kong 16 • Cape Town 17 • Wittenberg Exchange 19 • India 20 • Little Gidding 21 Prayer Groups 22 Theological Conversations 24 From Westcott to Williams: Sacramental Socialism and the Renewal of Anglican Social Thought 24 Living and Learning in the Federation 27 Chaplaincy 29 • ‘Ministry where people are’: a view of chaplaincy 29 A day in the life... • Bill Cave 32 • Simon Davies 33 • Stuart Hallam 34 • Jennie Hogan 35 • Ben Rhodes 36 New Developments 38 Westcott Foundation Programme of Events 2013-2014 38 Obituaries and Appreciations 40 Remembering Westcott House 48 Ember List 2013 49 Staff contacts 50 Members of the Governing Council 2012 – 2013 51 Editor Heather Kilpatrick, Communications Officer 2012 – 2013 THE YEAR IN REVIEW Foreword from the Bishop of Ely It is a great privilege to have become the Chair of the Council of“ Westcott House. As a former student myself, I am conscious just how much the House has changed through the years to meet the changing demands of ministry and mission in the Church of England, elsewhere in the Anglican Communion and in the developing ecumenical partnerships which the Federation embodies. We have been at the forefront in the deliberations which have led to the introduction of the Common Awards. -

2017.07 General Synod- Report

Report on the General Synod July 2017 Sessions at York. Introduction and welcomes. It is customary to invite several Anglican and Ecumenical guests to General Synod, of whom one is invited to address the Synod on behalf of all. The greeting this time was given by the Rt Revd Dr Matti Repo, Bishop of Tampere in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, who was welcomed and thanked by the Archbishop of York in, presumably, Finnish! Another guest of note was the Bishop of Edinburgh, the Rt Revd Dr John Armes, whose presence was felt by some to be controversial because of the Scottish Episcopal Church’s recent decision to approve same sex marriage. A letter in the Church Times suggested that a small number of synod members might stay away because of this but all were present, and a prolonged round of applause indicated that the majority were pleased to welcome Bishop John. Business Committee. Sue Booys the chair of the BC took time to shape the pattern of this Synod using the London agenda as a blue print. No more food at Fringe meetings! The main business of the day (Friday) was a debate on After the General Election, a still small voice of calm. She then told us about the Agenda for the next few days. It was recognised that there would be several presentations, maybe too many! The cost of synod was also raised and it was asked if it gave value for money. A theme of this synod would be engagement. We were told that Saturday evening would be the time for fringe meetings. -

Officers of the Society 1970-71

CONTENTS PAGE Frontispiece: Professor David Winton Thomas .. .. 4 Officers of the Society .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 News of the Society Notices and Reports .. .. .. .. .. 6-9 A Personal Note .. .. .. .. .. 9 St Catharine's Gild 10 The Society's Finances .. .. .. .. .. 11 The General Meeting of the Society, 1970 .. .. 12-13 The Quincentenary Appeal Accounts .. .. .. 14 The Quincentenary Accounts .. .. .. .. 15 The Annual Dinner, 1970 16-17 Engagements .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 Marriages .. .. .. .. .. .. 18-19 Births 19-20 Deaths 21 Obituaries 22-27 Ecclesiastical Appointments .. .. .. .. 28 Miscellaneous .. .. .. .. .. .. 29-36 Publications 37-39 News of the College College News Letter 40-43 The College Societies 44-50 Academic Distinctions .. .. .. .. .. 51-52 Articles The World of Music .. 53-54 ' Let us now praise famous men ' .. .. .. 54-55 Illustrations Interlude .. .. .. .. .. .. (facing) 10 Degree Day 1970 40 Another Year Ends .. .. .. .. .. 44 Professor David Winton Thomas Fellow of St Catharine's 1943-1969 SEPTEMBER 1970 Officers of the Society 1970-71 President Sydney Smith, PH.D., M.A. Vice-Presidents C. R. Allison, M.A. R. T. Pemberton C. Belfield Clarke, M.A. D. Portway, C.B.E., T.D., D.L., M.A. C. R. Benstead, M.C, M.A. The Reverend F. E. Smith, M.A. Sir Frank Bower, C.B.E., M.A. A. Stephenson, M.A. R. F. Champness, M.A., LL.M. A. H. Thomas, LL.D., M.A. R. Davies, C.M.G., M.A. Sir Augustus Walker, K.C.B., Sir Norman Elliott, C.B.E., M.A. C.B.E., D.S.O., D.F.C, M.A. A. A. Heath, M.A. E. Williamson, M.A. -

Open PDF 661KB

TRANSCRIPT OF ORAL EVIDENCE HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS MINUTES OF EVIDENCE TAKEN BEFORE THE ECCLESIASTICAL COMMITTEE CATHEDRALS MEASURE AND DIOCESAN BOARDS OF EDUCATION MEASURE TUESDAY 23 FEBRUARY 2021 10 am Virtual Proceeding Questions 1 - 14 Oral Evidence Taken before the Ecclesiastical Committee on Tuesday 23 February 2021 Members present: Baroness Butler-Sloss (Chair) Sir Peter Bottomley Mr Ben Bradshaw Fiona Bruce Dr Lisa Cameron Miriam Cates The Earl of Cork and Orrery Lord Cormack Baroness Eaton Lord Faulkner of Worcester Lord Field of Birkenhead Sir Roger Gale Lord Glenarthur Baroness Harris of Richmond Baroness Howarth of Breckland Lord Jones Lord Judd Lord Lexden Lord Lisvane Rachael Maskell Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall Andrew Selous Jim Shannon Stephen Timms Martin Vickers ________________ Examination of Witnesses The Very Reverend Andrew Nunn, Dean of Southwark; The Lord Bishop of Bristol; Dr Eve Poole, Third Church Estates Commissioner; Eva Abeles, Senior Advisory Lawyer; the Reverend Alexander McGregor, Chief Legal Adviser to the General Synod; William Nye, Secretary General; Christopher Packer, Legislative Counsel to the General Synod; The Lord Bishop of Durham; Clive Scowen, Chair, Revision committee; the Reverend Nigel Genders, Chief Education Officer. 1 Examination of witnesses The Very Reverend Andrew Nunn, The Lord Bishop of Bristol, Dr Eve Poole, Eva Abeles, the Reverend Alexander McGregor, William Nye, Christopher Packer, The Lord Bishop of Durham, Clive Scowen and the Reverend Nigel Genders. Q1 The Chair: I am very happy to open the public session of the virtual meeting of the Ecclesiastical Committee, which is entirely virtual. We are looking at two Measures today. -

DECEMBER 2015 Enormously

Chairman – Bishop Tim Thornton Vice Chairman – Reverend Steve Wild CTC Missioner – David H Smith Treasurer – Paul Durkin Charity No 1053899 www.churchestogetherincornwall “I listened to contributions which of course vary DECEMBER 2015 enormously. Some were very much in favour of the suggested changes and the direction of travel. Some were keen to keep to what they regard as the traditional teaching. “It was quite fascinating to observe how the meetings worked and what, if anything, happened in public and what happened behind the scenes. I was looking forward to being there and was fascinated to compare what I know and experience of the Church of England decision making process with what happened in Rome.” He added: “I was intrigued to hear whether we can all understand ourselves as we related one to another and to each one of us, as members of the human family.” Paris attacks: Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby admits doubting God, warns against military action The Rt Revd Tim Thornton, Bishop of Truro meets Pope Francis watched by the Revd Tim McQuiban, the Methodist fraternal delegate and a Methodist Minister in Rome PHOTO CREDIT: All image rights and copyrights reserved to the Photographic Service of L’Osservatore Romano The Rt Revd Tim Thornton, Bishop of Truro, says it is clear there are “major differences in the room” at the Roman Catholic Synod on the Family in Rome where he recently represented the Anglican church. Writing in his blog, Bishop Tim said the process was still The most senior bishop in the Church of England has admitted not clear or easy for many and mused on the difficulties of that the Paris attacks made him question the presence of God. -

Plusnet Leeds Half Marathon 10Th May 2015 Results

Plusnet Leeds Half Marathon 10th May 2015 Results Gender Class Chip Chip Pos. Bib Time Name Club Gender Pos Class Pos Time Pos 1 10801 1:11:18 Mohammad Aburezeq Altrincham & District AC Male 1 M 1 1:11:18 1 2 10324 1:12:08 Mike Burrett Leeds City Athletic Club Male 2 M35 1 1:12:08 2 3 10377 1:13:56 Alasdair Tatham North York Moors AC Male 3 M40 1 1:13:56 3 4 4184 1:14:26 John Hobbs Valley Striders AC Male 4 M35 2 1:14:24 4 5 10387 1:14:40 Dan Fisher Male 5 M 2 1:14:39 5 6 11548 1:14:52 Will Kerr Saltaire Striders Male 6 M35 3 1:14:52 6 7 4503 1:14:57 R Herrington St Theresa's A.C. Male 7 M35 4 1:14:56 7 8 5069 1:14:58 Paul Marchant Rothwell & District Harriers Male 8 M40 2 1:14:57 8 9 11434 1:15:25 Zak Tobias Bristol and West AC (est. 1882 Male 9 M 3 1:15:25 10 10 11429 1:15:26 Daniel Robinson Birmingham Running Athletics & Male 10 M35 5 1:15:24 9 11 4742 1:15:43 John Clifford Evenwood Road Runners Male 11 M40 3 1:15:43 11 12 4314 1:15:51 Andrew Redding Male 12 M35 6 1:15:50 12 13 4902 1:15:53 Richard Pattinson Horsforth Harriers Male 13 M50 1 1:15:51 13 14 4579 1:16:12 Liam O'Brien Hyde Park Harriers Male 14 M35 7 1:16:10 14 15 11552 1:16:26 Darren King Clowne Road Runners Club Male 15 M45 1 1:16:24 15 16 4384 1:16:39 Andy May Valley Striders AC Male 16 M40 4 1:16:39 16 17 11565 1:16:57 Chris Pickering Male 17 M 4 1:16:55 17 18 10932 1:17:12 Anthony Taylor Male 18 M40 5 1:17:07 18 19 11506 1:17:52 Jonathan Walton Leeds City Athletic Club Male 19 M45 2 1:17:52 19 20 4398 1:18:09 Frank Beresford Otley AC Male 20 M 5 1:18:09 20 21 744 1:18:11 -

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 5.20

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 5.20 OFFICE OF SECRETARY OF STATE COMMISSIONS PARDONS, 1836- Abstract: Pardons (1836-2018), restorations of citizenship, and commutations for Missouri convicts. Extent: 66 cubic ft. (165 legal-size Hollinger boxes) Physical Description: Paper Location: MSA Stacks ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Alternative Formats: Microfilm (S95-S123) of the Pardon Papers, 1837-1909, was made before additions, interfiles, and merging of the series. Most of the unmicrofilmed material will be found from 1854-1876 (pardon certificates and presidential pardons from an unprocessed box) and 1892-1909 (formerly restorations of citizenship). Also, stray records found in the Senior Reference Archivist’s office from 1836-1920 in Box 164 and interfiles (bulk 1860) from 2 Hollinger boxes found in the stacks, a portion of which are in Box 164. Access Restrictions: Applications or petitions listing the social security numbers of living people are confidential and must be provided to patrons in an alternative format. At the discretion of the Senior Reference Archivist, some records from the Board of Probation and Parole may be restricted per RSMo 549.500. Publication Restrictions: Copyright is in the public domain. Preferred Citation: [Name], [Date]; Pardons, 1836- ; Commissions; Office of Secretary of State, Record Group 5; Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City. Acquisition Information: Agency transfer. PARDONS Processing Information: Processing done by various staff members and completed by Mary Kay Coker on October 30, 2007. Combined the series Pardon Papers and Restorations of Citizenship because the latter, especially in later years, contained a large proportion of pardons. The two series were split at 1910 but a later addition overlapped from 1892 to 1909 and these records were left in their respective boxes but listed chronologically in the finding aid. -

Further Comments About BLESSSED ARE the POOR? by Laurie Green You Have in Your Hands a Rare and Special Document. Here Unearthed

Further comments about BLESSSED ARE THE POOR? by Laurie Green You have in your hands a rare and special document. Here unearthed for you are deep stories of hope and possibility as well as stories of hardship and dismay. These stories belong to the often forgotten residents of Britain’s housing estates. Laurie Green bears witness to how God is very present and how theology and church can become alive because of the mysterious part that those who are marginalised often play in the purposes of God. Ann Morisy Ann is a freelance community theologian, lecturer and author. Her best-selling books include Beyond the Good Samaritan and Journeying Out. This is an excellent book. If you are engaged in urban ministry, in housing estates, you will find a huge amount to help you understand the context, to challenge your thinking and to make your practice better. This book should also be read by all who have power in the church. Andy Delmege – convenor of the Estate Churches Group, Birmingham. This carefully researched but highly readable book combines detailed reflection on biblical resources with historical and sociological perspectives on housing estates and issues of urban poverty and, most significantly, the experience and stories of poor people themselves. Rejecting platitudes and romanticism, it is a powerful demonstration of the practice of contextual theology and offers a persuasive and provocative interpretation of what Jesus meant when he pronounced the poor 'blessed'. Stuart Murray Williams Stuart is a theologian and author, the founder of Urban Expression, and an experienced urban minister. He currently teaches mission and is Director of the Centre for Anabaptist studies. -

London Cornish Newsletter

Cowethas Kernewek Loundres www.londoncornish.co.uk Nadelik Lowen ha Blydhen Nowydh Da ternational awards and we know from what we read in the newsletters of other associa- When I started to write this, the news was full tions that there are many people with Cornish of the awful wildfires in California. This has links who do so much to promote Cornwall been such a tragedy that it is hard to get your and its heritage and would be excellent can- head around it. The sheer scale, the loss of didates. You know who in your area would fit Pre-Christmas life and the damage to the environment is the bill. Please nominate them and get them Lunch hard to comprehend. What is awful is that we the recognition they deserve. are hearing of more and more extreme 8th December weather conditions around the world, most In September, I was contacted by South Aus- 12 noon recently from Australia where Sydney had a tralian, Denise Philips, the Vice-president of month’s rain in two hours and thousands of the Hocking Descendants Society. We met New Year’s Lunch people have had to leave Gracemere, north up when she was in London and spent a 12th January 2019 of Brisbane, because of bushfire fears. Our delightful couple of hours together sharing 12 noon thoughts are with our ‘cousins’ in California news of our parts of the diaspora over a and ‘down under’ at this dreadful time. Cornish cream tea (complete with Rodda’s Richmond vs clotted cream!). You will find a report on this Cornish Pirates On a more cheerful note, there has been a lot elsewhere in the newsletter. -

This 2008 Letter

The Most Reverend and Right Hon the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury & The Most Reverend and Right Hon the Lord Archbishop of York July, 2008 Most Reverend Fathers in God, We write as bishops, priests and deacons of the Provinces of Canterbury and York, who have sought, by God’s grace, in our various ministries, to celebrate the Sacraments and preach the Word faithfully; to form, nurture and catechise new Christians; to pastor the people of God entrusted to our care; and, through the work of our dioceses, parishes and institutions, to build up the Kingdom and to further God’s mission to the world in this land. Our theological convictions, grounded in obedience to Scripture and Tradition, and attentive to the need to discern the mind of the whole Church Catholic in matters touching on Faith and Order, lead us to doubt the sacramental ministry of those women ordained to the priesthood by the Church of England since 1994. Having said that, we have engaged with the life of the Church of England in a myriad of ways, nationally and locally, and have made sincere efforts to work courteously and carefully with those with whom we disagree. In the midst of this disagreement over Holy Order, we have, we believe, borne particular witness to the cause of Christian unity, and to the imperative of Our Lord’s command that ‘all may be one.’ We include those who have given many years service to the Church in the ordained ministry, and others who are very newly ordained. We believe that we demonstrate the vitality of the tradition which we represent and which has formed us in our discipleship and ministry – a tradition which, we believe, constitutes an essential and invaluable part of the life and character of the Church of England, without which it would be deeply impoverished.