Low Cost Shore Protection a Property Owner's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GEOTEXTILE TUBE and GABION ARMOURED SEAWALL for COASTAL PROTECTION an ALTERNATIVE by S Sherlin Prem Nishold1, Ranganathan Sundaravadivelu 2*, Nilanjan Saha3

PIANC-World Congress Panama City, Panama 2018 GEOTEXTILE TUBE AND GABION ARMOURED SEAWALL FOR COASTAL PROTECTION AN ALTERNATIVE by S Sherlin Prem Nishold1, Ranganathan Sundaravadivelu 2*, Nilanjan Saha3 ABSTRACT The present study deals with a site-specific innovative solution executed in the northeast coastline of Odisha in India. The retarded embankment which had been maintained yearly by traditional means of ‘bullah piling’ and sandbags, proved ineffective and got washed away for a stretch of 350 meters in 2011. About the site condition, it is required to design an efficient coastal protection system prevailing to a low soil bearing capacity and continuously exposed to tides and waves. The erosion of existing embankment at Pentha ( Odisha ) has necessitated the construction of a retarded embankment. Conventional hard engineered materials for coastal protection are more expensive since they are not readily available near to the site. Moreover, they have not been found suitable for prevailing in in-situ marine environment and soil condition. Geosynthetics are innovative solutions for coastal erosion and protection are cheap, quickly installable when compared to other materials and methods. Therefore, a geotextile tube seawall was designed and built for a length of 505 m as soft coastal protection structure. A scaled model (1:10) study of geotextile tube configurations with and without gabion box structure is examined for the better understanding of hydrodynamic characteristics for such configurations. The scaled model in the mentioned configuration was constructed using woven geotextile fabric as geo tubes. The gabion box was made up of eco-friendly polypropylene tar-coated rope and consists of small rubble stones which increase the porosity when compared to the conventional monolithic rubble mound. -

Armoring the Coast: the Effects of Bulkheads on Salt Marsh Habitats

Armoring the Coast: The Effects of Bulkheads on Salt Marsh Habitats Presented by the Carolina Environmental Program Morehead City Field Site Students: Joseph Hester, Alison Kitto, Elizabeth Newland, Erika Poarch, Ashley Smyth and Zachary Williams Under the direction of Institute of Marine Sciences faculty members: Rachel T. Noble Michael F. Piehler Charles “Pete” Peterson Capstone Project: Carolina Environmental Program, Morehead City Field Site University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fall 2006 Acknowledgements This project was successful due to the combined efforts of many people. We would like to thank Rachel Noble for her words of wisdom and encouragement through the tough spots. Without Mike Piehler, this project would not have been successful. Mike was always available to answer questions and provide guidance. We thank Charles “Pete” Peterson, for just being Pete. Thanks to Reagan Converse for help in organizing this project and sorting through aerial photographs. Denene Blackwood is deserving of an extra special recognition. Her help in the field, on the boat, in the lab, and with questions was the reason this project was successful. Thanks to Suzanne Thompson for help with laboratory analysis. We would also like to thank everyone at UNC-IMS for their support and help throughout the semester. ii Abstract Shoreline hardening structures, such as bulkheads, are becoming an increasingly popular method of mitigating shoreline erosion. However, few studies have examined the ecological impacts of such structures. Salt marshes are highly productive ecosystems that act as a medium of exchange between marine and terrestrial environments. Bulkheads are thought to disrupt the natural processes associated with salt marshes. -

Shore Protection by Offshore Breakwaters

l§lHydraulics Research Wallingford SHORE PROTECTION BY OFFSHORE BREAKWATERS A H Brampton Ph .D J V Smallman Ph.D Report No SR 8 July 1985 Registered Office: Hydraulics Research Limited, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX 10 8BA. Telephone: 0491 35381. Telex: 848552 Thi s report describes work carri ed out wi thin the research programme Commission B for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheri es and Food . The study was carri ed ou t in the Coas tal Processes Sect ion of the Mari time Engineering Department of Hydraulics Research . The departmental nominated officer is Mr A Alli son . The Company's nominated project officer is Dr S W Huntington. The report is publi s hed on behalf of MAFF but any op inions expressed are not necessarily those of the Ministry . C Crown copyri ght 19 85 ABSTRACT This report reviews the information available for the design and use of offshore breakwaters in shore protection. As an introduction to the subject the physical processes occurring in the lee of an offshore breakwater are described with reference to natural examples. This is followed by a survey of case histories, and mathematical and physical modelling techniques for offshore breakwaters. Some of the methods which are available for the design of a breakwater system are reviewed. Possible future developments in the design process are described, and the areas in which further research on the effects of offshore breakwaters is required are highlighted. CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OFFSHORE BREAKWATERS - THE PHYSICAL PROCESSES 2 2.1 Natural Examples 2 2.2 Physical processes 4 3 LITERATURE STUDY 6 3.1 Review of case histories 6 3.2 Physical model studies 10 3 .3 Ma thematical model studies 16 4 DESIGN METHODS FOR AN OFFSHORE BREAKWATER SYSTEM 19 4.1 Developing the initial design 19 4.2 Methods for improving the breakwa ter design 22 5 FUTURE DEVELOPMENT 26 6 CONCLUS IONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 28 7 ACKNOWLEDGE MENTS 29 8 REFERENCES 30 FIGURES PLATES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. -

The Impact of Submerged Breakwaters on Sediment Distribution Along Marsh Boundaries

water Article The Impact of Submerged Breakwaters on Sediment Distribution along Marsh Boundaries Iacopo Vona *, Matthew W. Gray and William Nardin Horn Point Laboratory, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Cambridge, MD 21613, USA; [email protected] (M.W.G.); [email protected] (W.N.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 February 2020; Accepted: 31 March 2020; Published: 2 April 2020 Abstract: Human encroachment and development on coastlines have led to greater amounts of armoring of shorelines. Breakwaters are a common feature along coastlines, which are used to dampen wave energy and protect shorelines from flash floods or overwash events. Although common, their effects on sediment transport and marsh geomorphology are poorly understood. To address this gap, our study quantifies the effects of breakwaters on sediment transport and marsh evolution under different wave regimes using Delft3D-SWAN, a dynamic geomorphodynamic numerical model. Model configurations used the same numerical domain, but scenarios had different sediments, waves, tides, basin slopes and breakwater distances from the shoreline to explore how waves and tidal currents shape coastal margins. Model results suggested breakwaters were responsible for an average wave damping between 10–50%, proportional to the significant wave height across all modeled scenarios. Shear stress at the beginning of the marsh and the volume of sediment deposited at the end of the simulation (into the marsh behind the breakwater) increased on average between 20–40%, proportional to the slope and distance of the breakwater from the shoreline. Sediment trapping, defined as the ratio between the volume of sediment housed into the salt marsh behind and away from the breakwater, was found to be less than 1 from most model runs. -

Harbor Protection Through Construction of Artificial Submerged Reefs

Harbor Protection through Construction of Artificial Submerged Reefs Amarjit Singh, Vallam Sundar, Enrique Alvarez, Roberto Porro, Michael Foley (www.hawaii.gov) 2 Outline • Background of Artificial Reefs • Multi-Purpose Artificial Submerged Reefs (MPASRs) ▫ Coastline Protection ▫ Harbor Protection • MPASR Concept for Kahului Harbor, Maui ▫ Situation ▫ Proposed Solution • Summary 3 Background First documented First specifically Artificial reefs in First artificial reef Artificial reefs in artificial reefs in designed artificial Hawaii– concrete/tire in Hawaii Hawaii – concrete Z- U.S. reefs in U.S. modules modules 1830’s 1961 1970’s 1985-1991 1991- Present • Uses • Materials ▫ Create Marine Habitat ▫ Rocks; Shells ▫ Enhance Fishing ▫ Trees ▫ Recreational Diving Sites ▫ Concrete Debris ▫ Surfing Enhancement ▫ Ships; Car bodies ▫ Coastal Protection ▫ Designed concrete modules ▫ Geosynthetic Materials 4 Multi-Purpose Artificial Submerged Reefs (MPASRs) Specifically designed artificial reef which can provide: • Coastline Protection or Harbor Protection ▫ Can help restore natural beach dynamics by preventing erosion ▫ Can reduce wave energy transmitted to harbor entrances • Marine Habitat Enhancement ▫ Can provide environment for coral growth and habitat fish and other marine species. ▫ Coral can be transplanted to initiate/accelerate coral growth • Recreational Uses ▫ Surfing enhancement: can provide surfable breaking waves where none exist ▫ Diving/Snorkeling: can provide site for recreational diving and snorkeling 5 MPASRs as Coastal Protection Wave Transmission: MPASRs can reduce wave energy transmitted to shoreline. Kt = Ht/Hi K = H /H t t i Breakwater K = wave transmission t Seabed coefficient, (Pilarczyk 2003) Ht= transmitted wave height shoreward of structure Hi = incident wave height seaward of structure. 6 MPASRs as Coastal Protection • Wave Refraction: MPASR causes wave refraction around the reef, focusing wave energy in a different direction. -

Shoreline Stabilisation

Section 5 SHORELINE STABILISATION 5.1 Overview of Options Options for handling beach erosion along the western segment of Shelley Beach include: • Do Nothing – which implies letting nature take its course; • Beach Nourishment – place or pump sand on the beach to restore a beach; • Wave Dissipating Seawall – construct a wave dissipating seawall in front of or in lieu of the vertical wall so that wave energy is absorbed and complete protection is provided to the boatsheds and bathing boxes behind the wall for a 50 year planning period; • Groyne – construct a groyne, somewhere to the east of Campbells Road to prevent sand from the western part of Shelley Beach being lost to the eastern part of Shelley Beach; • Offshore Breakwater – construct a breakwater parallel to the shoreline and seaward of the existing jetties to dissipate wave energy before it reaches the beach; and • Combinations of the above. 5.2 Do Nothing There is no reason to believe that the erosion process that has occurred over at least the last 50 years, at the western end of Shelley Beach, will diminish. If the water depth over the nearshore bank has deepened, as it appears visually from aerial photographs, the wave heights and erosive forces may in fact increase. Therefore “Do Nothing” implies that erosion will continue, more structures will be threatened and ultimately damaged, and the timber vertical wall become undermined and fail, exposing the structures behind the wall to wave forces. The cliffs behind the wall will be subjected to wave forces and will be undermined if they are not founded on solid rock. -

Functional Design of Coastal Structures

FUNCTIONALFUNCTIONAL DESIGNDESIGN OFOF David R. Basco, Ph.D, P.E. Director, The Coastal Engineering Center Old Dominion University,Norfolk, Virginia USA 23529 [email protected] DESIGNDESIGN OFOF COASTALCOASTAL STRUCTURESSTRUCTURES •• FunctionFunction ofof structurestructure •• StructuralStructural integrityintegrity •• PhysicalPhysical environmentenvironment •• ConstructionConstruction methodsmethods •• OperationOperation andand maintenancemaintenance OUTLINEOUTLINE •• PlanPlan formform layoutlayout - headland breakwaters - nearshore breakwaters - groin fields • WaveWave runuprunup andand overtopping*overtopping* - breakwaters and revetments (seawalls, beaches not covered here) •• WaveWave reflectionsreflections (materials(materials includedincluded inin notes)notes) * materials from ASCE, Coastal Engineering Short Course, CEM Preview, April 2001 SHORESHORE PARALLELPARALLEL BREAKWATERS:BREAKWATERS: HEADLANDHEADLAND TYPETYPE Design Rules, Hardaway et al. 1991 • Use sand fill to create tombolo for constriction from land • Set berm elevation so tombolo always present at high tide • Set Yg/Lg =• 1.65 for stable shaped beach • Set Ls/Lg = 1 • Always combine with new beach fill • See CEM 2001 V-3 for details KEYKEY VARIABLESVARIABLES FORFOR NEARSHORENEARSHORE BREAKWATERBREAKWATER DESIGNDESIGN Dally and Pope, 1986 Definitions: Y = breakwater distance from nourished shoreline Ls = length of breakwater Lg = gap distance d = water depth at breakwater (MWL) ds = water depth• at breakwater (MWL) •Tombolo formation: Ls/Y = 1.5 to 2 single = 1.5 system •Salient formation: Ls/ = 0.5 to 0.67 = 0.125 long systems (a) (b) Process Parameter Description 1. Bypassing Dg/Hb Depth at groin tip/breaking wave height 2. Permeability • Over-passing Zg (y) Groin elevation across profile, tidal range • Through-passing P(y) Grain permeability across shore • Shore-passing Zb/R Berm elevation/runup elevation 3. Longshore transport Qn/Qg Net rate/gross rate Property Comment 1. Wave angle and wave height Accepted. -

A Case Study of the Holly Beach Breakwater System Andrew Keane Woodroof Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2012 Determining the performance of breakwaters during high energy events: a case study of the Holly Beach breakwater system Andrew Keane Woodroof Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Woodroof, Andrew Keane, "Determining the performance of breakwaters during high energy events: a case study of the Holly Beach breakwater system" (2012). LSU Master's Theses. 2184. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2184 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DETERMINING THE PERFORMANCE OF BREAKWATERS DURING HIGH ENERGY EVENTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE HOLLY BEACH BREAKWATER SYSTEM A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering by Andrew K. Woodroof B.S., Louisiana State University, 2008 December 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my love and passion for the infinite beauty of south Louisiana. The vast expanse of wetlands, coastlines, and beaches in south Louisiana harbors people, industry, natural resources, recreation, and wildlife that is truly special. The intermingling of these components creates a multitude of unique cultures with such pride, passion, and zest for life that makes me thankful every day that I can enjoy the bounty of this region. -

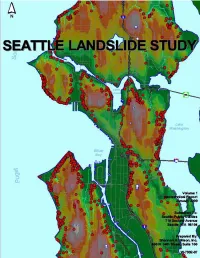

Landslide Study

Department of Planning and Development Seattle Landslide Study TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1. GEOTECHNICAL REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PREFACE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose 1.2 Scope of Services 1.3 Report Organization 1.4 Authorization 1.5 Limitations PART 1. LANDSLIDE INVENTORY AND ANALYSES 2.0 GEOLOGIC CONDITIONS 2.1 Topography 2.2 Stratigraphy 2.2.1 Tertiary Bedrock 2.2.2 Pre-Vashon Deposits 2.2.3 Vashon Glacial Deposits 2.2.4 Holocene Deposits 2.3 Groundwater and Wet Weather 3.0 METHODOLOGY 3.1 Data Sources 3.2 Data Description 3.2.1 Landslide Identification 3.2.2 Landslide Characteristics 3.2.3 Stratigraphy (Geology) 3.2.4 Landslide Trigger Mechanisms 3.2.5 Roads and Public Utility Impact 3.2.6 Damage and Repair (Mitigation) 3.3 Data Processing 4.0 LANDSLIDES 4.1 Landslide Types 4.1.1 High Bluff Peeloff 4.1.2 Groundwater Blowout 4.1.3 Deep-Seated Landslides 4.1.4 Shallow Colluvial (Skin Slide) 4.2 Timing of Landslides 4.3 Landslide Areas 4.4 Causes of Landslides 4.5 Potential Slide and Steep Slope Areas PART 2. GEOTECHNICAL EVALUATIONS 5.0 PURPOSE AND SCOPE 5.1 Purpose of Geotechnical Evaluations 5.2 Scope of Geotechnical Evaluations 6.0 TYPICAL IMPROVEMENTS RELATED TO LANDSLIDE TYPE 6.1 Geologic Conditions that Contribute to Landsliding and Instability 6.2 Typical Approaches to Improve Stability 6.3 High Bluff Peeloff Landslides 6.4 Groundwater Blowout Landslides 6.5 Deep-Seated Landslides 6.6 Shallow Colluvial Landslides 7.0 DETAILS REGARDING IMPROVEMENTS 7.1 Surface Water Improvements 7.1.1 Tightlines 7.1.2 Surface Water Systems - Maintenance -

A Roman Watchtower on the Gask Frontier W S Hanson* & J G P Friellf

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, (1995)5 12 , 499-519 Westerton: a Roman watchtower on the Gask frontier W S Hanson* & J G P Friellf ABSTRACT The excavation of the Roman timber watchtower at Westerton was undertaken to obtain dating evidence and a complete plan. The four-post tower was more elongated in plan than anticipated provided frontwas the at and with steps giving accessfirst-floorthe to level,a feature readilynot paralleled excavatedin towers anywhere Romanthe in Empire.one The fragment f probableo mortarium recovered frome singleth enclosing ditch s commensuratei with a Flavian date. Disturbance of the post-holes indicated that the tower had been deliberately demolished. The tower consideredis relationin otherto adjacent examples which Gask makethe up frontier. The function of this system is discussed and placed in its broader historical context. INTRODUCTION existence Th seriea f eo f timbe o s r towers alon Gase gth k Ridg lons eha g been known beste Th . - preserved examples follow the line of the Roman road to the east of the fort at Strageath along this low ridge of hills, which runs approximately east/west immediately to the north of the river Earn. e numbeTh f siteo r s know s grownha n ove pase , largelyear0 th rso 5 t r o sy through aerial reconnaissance resulta s A . , somattested w tower7 1 eno e e distributiosar th , f whicno h extends beyon Gase dth k Ridg enorth-easte botth o ht , towarde th o fore t t Berth Taye sth a d t th an , n ao south, past the fort at Ardoch (illus 1). -

Self-Taught Education Unit Coastal Shoreline Defense Structures by Thomas Barnard

Self-Taught Education Unit Coastal Shoreline Defense Structures By Thomas Barnard Objectives The purpose of this self-taught education unit is to acquaint the reader with the various types of shoreline defense structures which are employed in the Chesapeake Bay region and the U.S. in general. There are more erosion control measures than those explained here but these are the most generally used and accepted within the marine community. Each structure will be defined and its use along the shoreline will be described. General design and location considerations will be discussed as well as the general definitions and terminology neces- sary for each type of structure. Following completion of this study unit, the reader will be generally acquainted with: 1. Shoreline erosion and its causes; 2. The types of structures most often employed to address shoreline erosion; 3. General design considerations for each shoreline structure; 4. Specific definitions and terminology for each structure. Introduction At the present time the Chesapeake Bay and most areas of the east and gulf coasts are experiencing varying degrees of relative sea level rise. This is defined as the net change in water elevation due to the combined influence of local land movement (subsidence) and the absolute change in water level. The primary result of sea level rise is shoreline retreat (erosion) along with other secondary shoreline changes. Chesapeake Bay sea level rise is approximately one foot per century at present. There is some evidence that sea level rise is accelerating due to global climate change. This factor has not been completely documented however, primarily due to the difficulty involved with modelling weather and climate features on a global scale and determining long term trends in the absence of adequate data. -

Prisoners Harbor Coastal Wetland Restoration Project

Channel Islands National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Prisoners Harbor Coastal Wetland Restoration Project Final Environmental Impact Statement February 2010 Channel Islands National Park 1901 Spinnaker Drive Ventura, California 93001 This entire publication is available in PDF format at: http://www.nps.gov/chis/parkmgmt/planning.htm Front cover photo: Mouth of Cañada del Puerto creek, Prisoners Harbor, Channel Islands National Park (Power, 2006) Citation: National Park Service. 2010. Prisoners Harbor Coastal Wetland Restoration Plan. Channel Islands National Park, Ventura, CA. PRISONERS HARBOR COASTAL WETLAND RESTORATION PLAN FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Channel Islands National Park Santa Cruz Island, Santa Barbara County, California February, 2010 ABSTRACT This Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) was prepared in accordance with the Department of Interior National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the National Park Service NEPA guidelines (DO-12), and the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). This document has been prepared because actions proposed as part of this Final EIS may be a major federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment. The National Park Service (NPS) proposes to restore a functional, self-sustaining ecosystem at a coastal wetland site known as Prisoners Harbor and a 40-acre associated stream corridor in the lower Cañada del Puerto Creek on Santa Cruz Island. The project seeks to: (1) recreate a more natural topography and hydrology by reconnecting the Cañada del Puerto stream with its floodplain and removing non-native eucalyptus trees and other vegetation which have proliferated in the lower drainage; (2) increase biological diversity and productivity by removing fill and restoring the historic wetland; (3) provide an enhanced visitor experience by installing viewing benches and additional interpretive displays; and (4) protect significant cultural and historic resources.